Best experienced with sound

Scroll to start

They appear almost like clockwork…

Blanketing backyards, parks and towns in a historic emergence that hasn’t occurred in more than 200 years.

Cicadas rising

A visual guide to 2024’s rare dual appearance

Published May 3, 2024

Billions of bugs are emerging from the soil across a large swath of the United States in a natural phenomenon last witnessed in 1803.

It involves two broods, or groups, of periodical cicadas, insects with relatively long life cycles that show up after a certain interval. The Northern Illinois brood spends 17 years underground before surfacing and is known as Brood XIII, while the Great Southern Brood, or Brood XIX, lives underground for 13 years.

“What's so stunning is that they're here all along … but because they're underground everybody forgets about them,” said cicada expert John Lill, a professor of biology at George Washington University.

The synchronous dual emergence of these two particular broods, which happens once every 221 years, is underway until June. The next time the two broods appear together, it will be 2245.

Learn all about cicadas by selecting each of the four sections below

Where you'll find them

More than 3,000 species of cicadas are found all around the globe, but just nine are periodical, and of those, seven — all part of a genus known as Magicicada — only inhabit the eastern United States. Other cicada species appear every year later in the summer.

A brood can contain more than one species, and all seven US periodical varieties will appear this spring.

“The densest places they live coincide with where people are. They love the edges (of cities), like woodlots and suburbs and even urban areas, older neighborhoods with big trees. They're very prominent in (inhabited) areas,” Lill said.

“It's not like something happening way out in the countryside that nobody pays attention to,” he added. “It's going to happen in downtown Chicago.”

The largest city in the vicinity of Brood XIII, the Northern Illinois brood, is Chicago.

The biggest cities in the range of Brood XIX, the Great Southern brood, include St. Louis, Nashville, and Charlotte, North Carolina.

The two broods could encounter one another around Springfield, Illinois, where it’s possible members of the different species could mate, resulting in hybrid cicadas.

However, it’s unlikely that would mess up the bugs’ internal clocks, Lill said; more likely their offspring would adopt either a 13- or 17-year cycle. And scientists don’t expect any area of overlap between the two broods to be very broad.

The first sign that cicada season is imminent is the appearance of small holes in the soil, often near tree roots. Triggered by soil temperature, the holes can show up weeks before the insects begin to emerge.

“Sixty-four degrees Fahrenheit (17.8 C) seems to be the magic number,” Lill said. “That's when they get the cue to come up on time. And it’s fascinating how quickly it happens.”

While the Northern Illinois and Great Southern broods haven’t been spotted in the same year since 1803, emergences involving two of the roughly 15 broods of periodical cicadas happen relatively frequently. The last dual emergence occurred in 2015; it’ll happen again in 2037.

Outside the US, periodical cicadas appear in Fiji and in India, where there is a brood known as the World Cup cicadas because they appear once every four years in tandem with the soccer tournament.

Choose another section below

Why they’re here now

Source: Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

The cicadas have one aim in the few weeks they spend above ground: to breed and lay eggs to create the next generation of cicadas before they die. First, however, they have to become full-fledged adults.

Once a cicada emerges from a tunnel, its first goal is to find a vertical surface. Typically a tree, or a fence post, is where the bug sheds its exoskeleton and spreads its wings for the first time. (You can find the brown “shells” of skin cicadas leave behind, called exuviae, on tree trunks.)

“They’re driven to climb,” Lill said. “Once they reach a certain height they stop and start this molting process. They crack open the back of their exoskeleton and do this really elaborate backbend followed by a big sit-up and then they (break out).”

This transition happens at night. “It's really kind of a ghostly event,” he said.

By morning, the bugs’ bodies have expanded, hardened and changed color. An inch or two long, the cicadas sport glistening black-and-orange torsos and bright red eyes. With newly unfurled wings, members of the brood gather in trees where they begin to mate.

When was the last time we saw a dual emergence of these broods?

Choose another section below

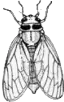

What they look like

When cicadas first molt, they are whitish in color. Gradually, their bodies turn black.

Some Magicicada species have orange stripes on their abdomens.

The bugs’ eyes are red, and their wings are clear with distinctive orange veins.

Periodical cicadas embody a biological phenomenon known as “predator satiation.”

Their only defense against an array of natural predators — including birds, squirrels and pet dogs — is the fact that the bugs arrive in such enormous numbers and their arrival is hard to anticipate since it doesn’t happen every year.

“During the peak of the emergence … only about 15% of them get eaten so 85% survive and that means tons reproduce the next generation,” Lill said.

“They just win by their sheer numbers and the fact that except for humans, no other organisms can anticipate their arrival in any meaningful way.”

Nevertheless, as with most living creatures, cicadas are already beginning to feel the effects of the climate crisis. Having spent most of their lives underground, the development of cicada babies is highly dependent on soil moisture.

But early springs and warm rain events are heating up the soil, causing cicadas to come out earlier than usual, according to Chris Simon, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Connecticut.

“Growing seasons are getting longer, and the longer the growing season, the more cicadas can grow each year,” Simon told CNN, noting that if the 17-year cicadas grow faster, they could come out four years earlier.

Simon said these “straggling events,” or cicadas emerging off-cycle, are “unprecedented.”

“Because of the warming trend, these four-year early emergences are happening in such a big way that they might become established,” she said. All the 13-year cicadas in the Upper Midwest, for example, were recently 17-year cicadas. And in 2017, some populations of Brood X emerged four years earlier than their usual 17 years.

How does one cicada compare with the sizes of other insects?

Periodical cicada

1.5" long (body)

European mantis

3" long

Ladybug

0.4" long

Darkling beetle

0.6" long

Cockroach

1.6" long

Earwig

1" long

Giant water bug

2" long

Ant

0.09" long

Note: Approximate measurements, excludes antennae and wings of insects

Sources: National Geographic, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Harvard University, University of Florida, Missouri Department of Conservation, University of Kentucky. Photo credit: Getty Images

Choose another section below

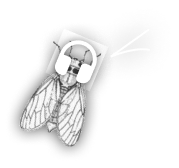

What they sound like

Click and hold to hear me sing

The song of Magicicada cassini. Credit: Macaulay Library

Large numbers of male cicadas congregate in individual trees and burst into song to attract their female counterparts.

The males produce this call with an organ known as the tymbal that clicks when a cicada flexes its muscles. Enough separate clicks coalesce into a surprisingly loud sound known as the cicada chorus.

See how one cicada compares with these other sounds

Note: Experiencing noise levels exceeding 85 decibels does not necessarily lead to hearing damage. Most noise-induced hearing loss is caused by repeated or long-exposure to hazardous noise, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Decibel levels may fluctuate depending on environmental factors and proximity to the sound source.

Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office of Scientific and Technical Information, Royal National Institute for Deaf People, American Speech–Language–Hearing Association, Purdue University, Photo credit: Getty Images, AP

“It's like the decibel (level) of a trash truck but it's buzzy. And the species (calls) are all very different. Some of them sound like a UFO or a drone and they go loud and soft. And others have little clicks associated with them,” Lill said.

Female cicadas don’t have the same noise-making apparatus but are able to click their wings and use other behavior to signal their interest in potential mates.

Source: “Insects, their ways and means of living” – Smithsonian Institution series (illustrations have been edited)

Choose another section below