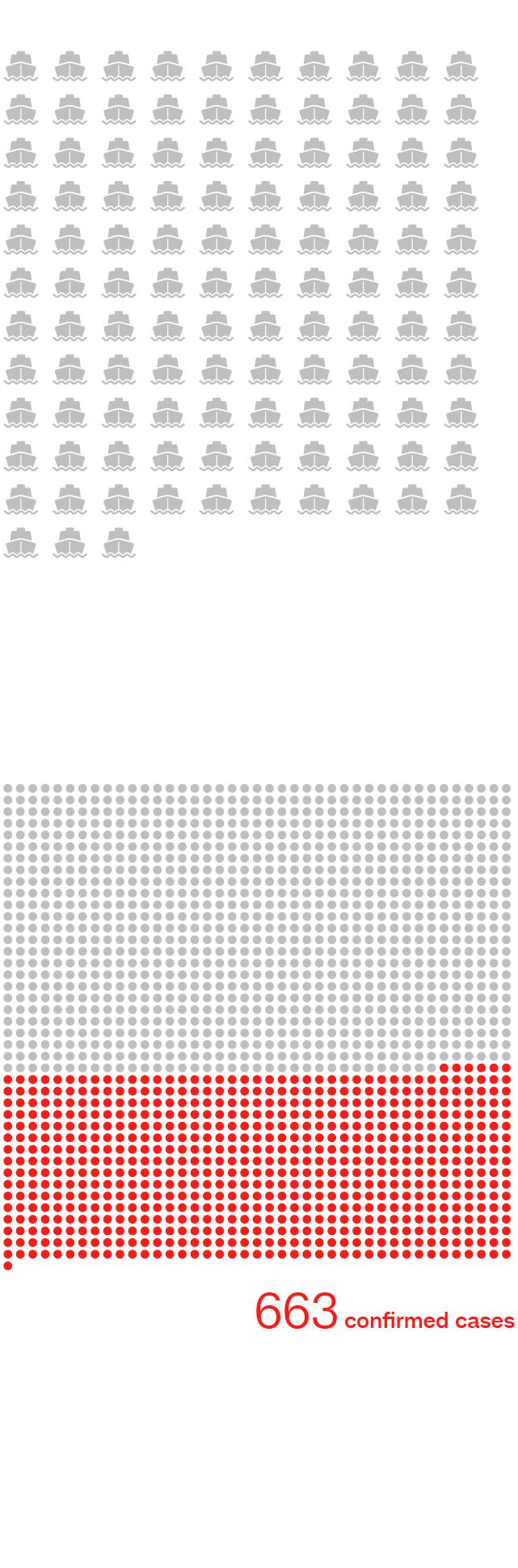

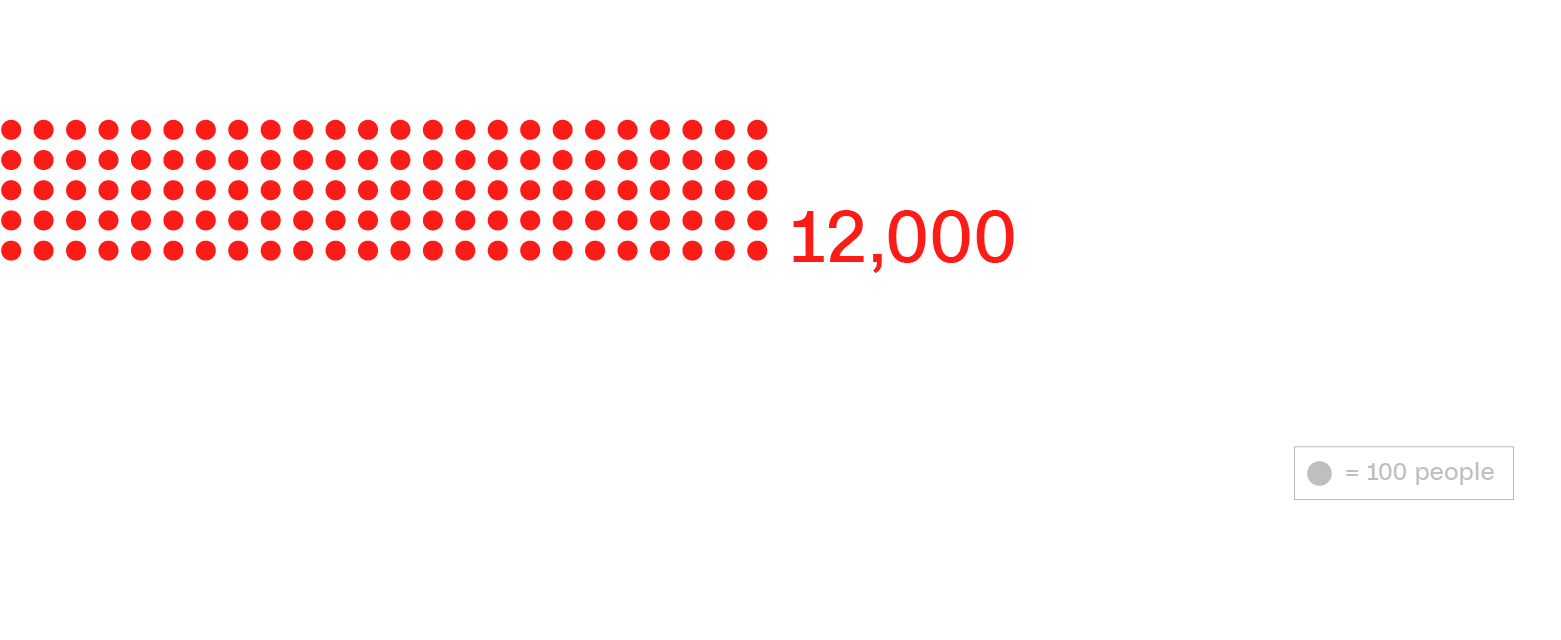

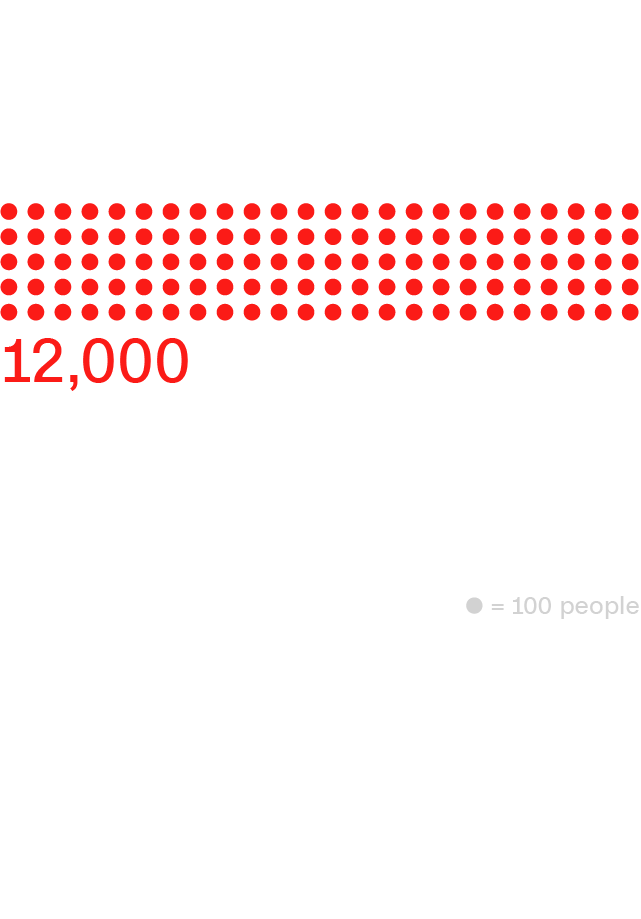

Each dot represents one human life lost

One million dead: How Covid-19 tore us apart

A virus that has affected the world

A Chinese doctor who tried to sound the alarm. A father of six who emigrated from Pakistan to the United States to give his family a better life. A 15-year-old boy who left his remote home in the Amazon to study. They all died from Covid-19.

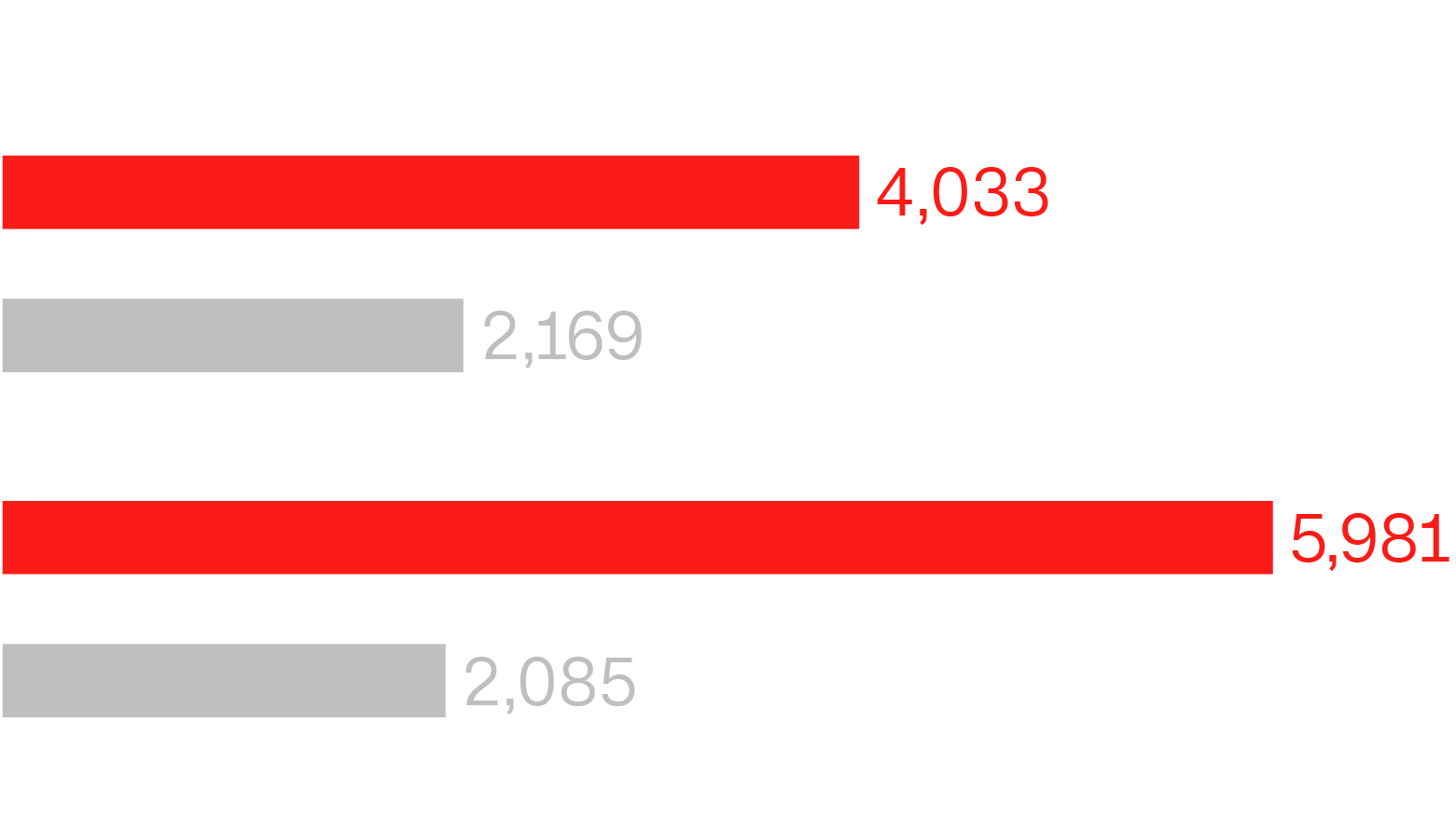

In eight months, more than 33 million people have been diagnosed with coronavirus, across nearly every country. The disease has taken lives on every continent except Antarctica -- and more than one million people have died.

That’s four times as many people who died in the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, 16 times as many people killed by the common flu in the US last winter, and more than 335 times the number of people who perished in the 9/11 attacks.

But the tragedy of coronavirus isn’t just in the death toll. It’s also in the grim truths it has revealed about who we are and how we treat our most vulnerable. The pandemic has exposed shocking failures of governance, worsened deep-rooted inequalities in access to healthcare, and inflamed a long-waged war on facts preventing scientists from conveying information that could save lives.

Almost every person in the world has been affected by the pandemic. But it hasn’t drawn us closer -- in many ways, it’s tearing us further apart.

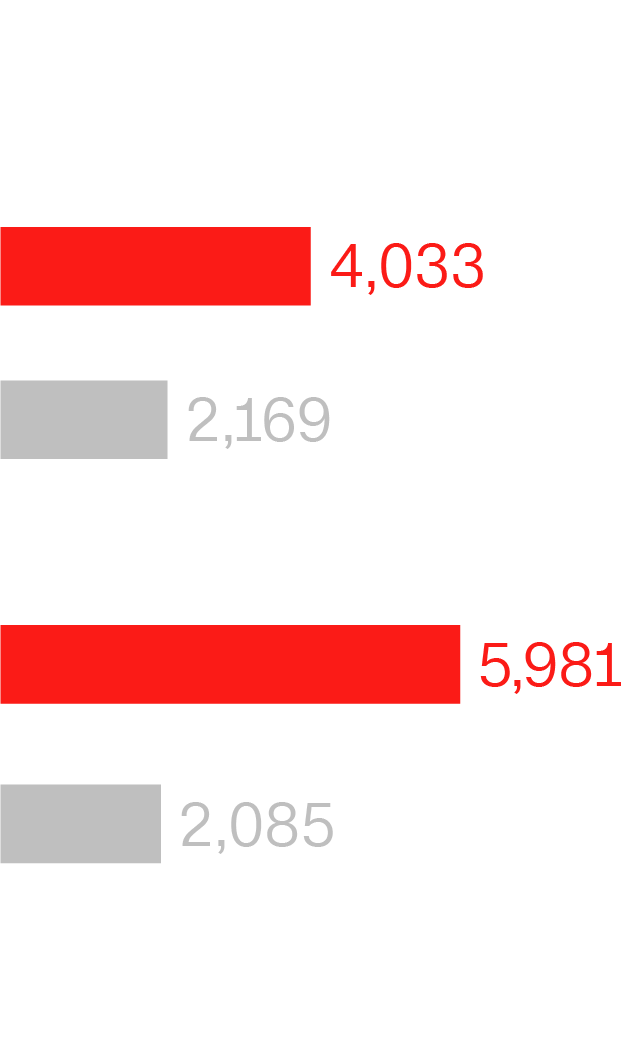

Asia

deaths

When the poor pay the price

Credit: Family handout

This is Vinod Kumar.

He died April 24, 2020, age 57.

Each day, Vinod Kumar collected trash and swept the streets of India’s capital, New Delhi, to provide for his family. Ultimately, it cost him his life.

In March, when India went into a nationwide lockdown, New Delhi’s normally hectic streets emptied as people stayed home to shield themselves from the virus. But 57-year-old Kumar was the family’s sole income earner -- he had to keep working.

“He always did his work to the fullest even though he was old,” says his 27-year-old son, Sumit Vinod. “He never left his work half done.”

Covid-19 cases were found in the areas Kumar collected waste, but the Delhi authorities that employed him did not provide personal protective equipment or a test for the virus, Vinod said. Vinod tried to take Kumar to a private hospital, where he hoped there’d be less risk of infection, but was told admission would cost 35,000 Indian rupees ($475) -- his father’s monthly salary. At a government hospital, Kumar had to pay 3,100 rupees for treatment. Vinod borrowed money from friends and family to pay the bill.

“There wasn't even a stretcher for us to carry him on, which made things difficult because he was already breathless and found it hard to stand. It took eight hours for him to finally get a bed," Vinod said.

On April 24, six days after he was admitted to hospital, Kumar died. His son said he received no compensation from his employer. Jai Prakash, senior official of the Municipal Corporation of Delhi, said workers had been provided with gloves and masks since April, and those who showed symptoms were tested. Family members of workers who died of Covid-19 received 10 million rupees ($136,000) within six weeks, he said.

"I don't know if better treatment could have saved him, but what we went through was very difficult,” Vinod said. “Definitely, if we had money, that would not be the case.”

Like many countries, India has a vast wealth divide. Low-income workers have suffered the most during its pandemic — the second largest in the world with more than six million cases.

That gap yawned wider as the country went into a sudden, hard lockdown in March. Millions of migrant workers became trapped in cities, without jobs or a means to get home. While middle-class Indians could work from home and socially distance from their neighbors, daily-wage earners had no choice but to keep going to work. For those living in densely packed slums, social distancing was impossible. Access to medical care for India’s poorest Covid-19 patients is far from guaranteed.

It’s a global problem. Research published in April by the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research says 30 years of progress in reducing global poverty is starting to unravel. It predicts the coronavirus could push half a billion people into poverty worldwide.

The pandemic hasn’t just highlighted the wealth gap -- it’s made it worse.

Oceania

deaths

We were warned

Credit: Family handout

This is Karla Lake.

She died March 29, 2020, age 75.

Karla Lake and her husband, Graeme, 73, boarded the luxury Ruby Princess cruise ship in Sydney on March 8 -- the same day Australian health authorities said the risk of contracting coronavirus in the country was low.

After meeting three decades ago on a blind date, the couple had settled into retirement, taking dozens of cruises like this one to New Zealand, for Karla’s 75th birthday.

But this time, as they circumnavigated New Zealand, sailing past the towering mountains of Fiordland and the art deco buildings of Napier, coronavirus was spreading on board -- something they only learned back home. On land, they tested positive and were admitted to hospital. Within 10 days, Karla was dead.

“Karla went to sleep at about 3 p.m. on the Saturday afternoon and I wasn’t aware that was the last time I was ever going to speak to her,” Graeme said. “I didn’t get the opportunity to tell her how much I loved her.”

An Australian Commission of Inquiry has identified several serious errors in relation to the Ruby Princess, including authorities’ failure to isolate and test suspected cases. More than 3,000 passengers and crew were given permission to disembark and scatter worldwide, despite a significant spike in flu-like symptoms among passengers. About 850 Australian passengers and crew had contracted Covid-19. There are 28 Covid-19 deaths associated with the ship, including Karla Lake.

Graeme and 900 fellow passengers have launched a class action lawsuit against the Ruby Princess’ operator, Princess Cruises, alleging it was negligent and failed in its duty to provide a safe cruise. Princess Cruises declined to comment due to pending litigation.

“If they had told me that there was sickness on the ship, I might have had the opportunity to say to Karla, let’s stay in the cabin and isolate, so she didn’t get sick,” Graeme said.

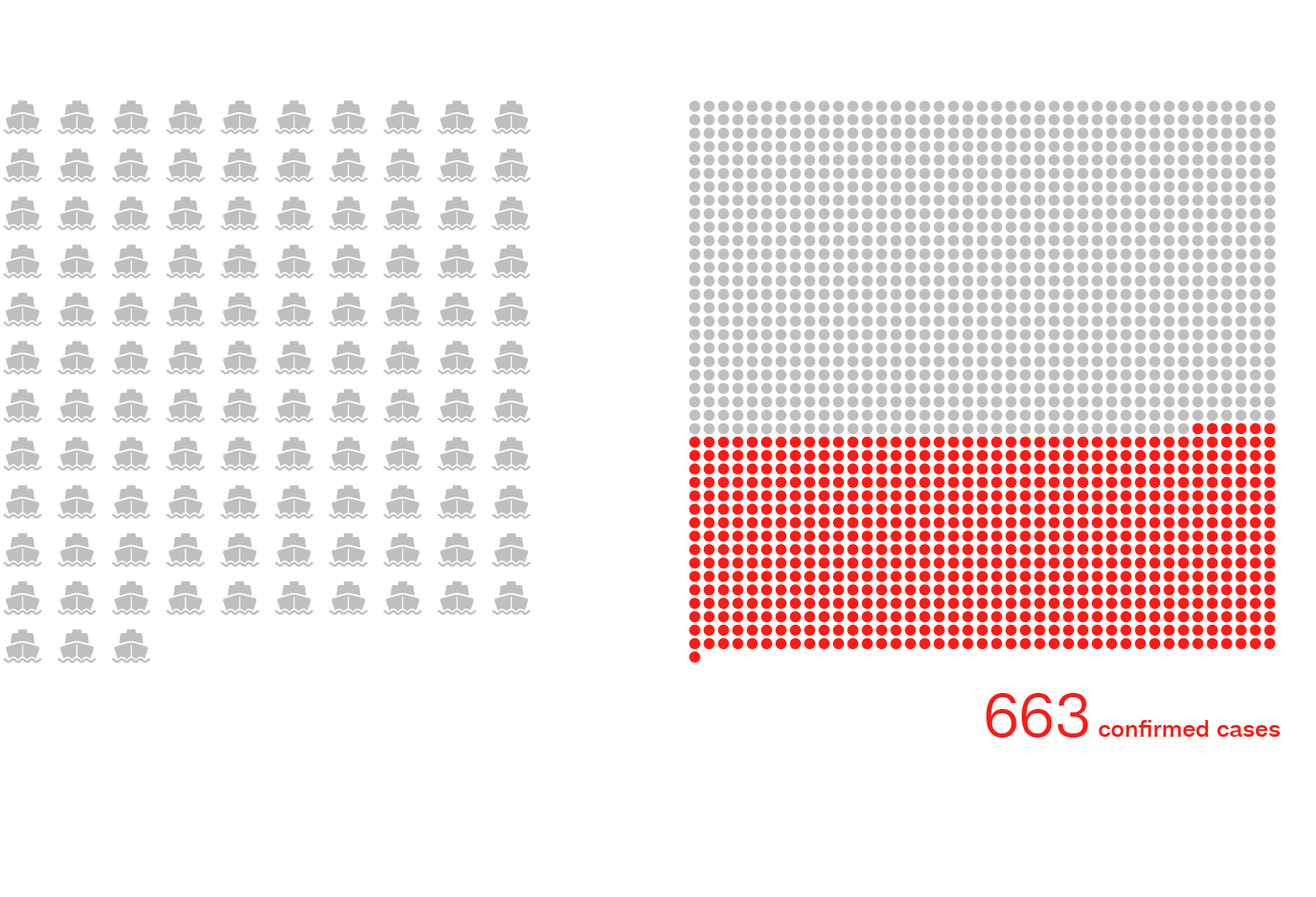

In the early days of the pandemic, some of the largest coronavirus clusters were on cruise ships carrying holidaymakers around the globe. In February, the Diamond Princess, docked off the coast of Japan, had the biggest outbreak outside of mainland China.

These closed societies at sea served as microcosms of the crisis unfolding around the world.

The Ruby Princess, and other ships, illustrated how quickly the virus could spread. It also provided governments with early lessons: act swiftly, be transparent with the public and ensure widespread testing is available.

Unfortunately, not all governments heeded those warnings.

Europe

deaths

An assault on the elderly

Credit: Family handout

This is Michael Gibson.

He died April 3, 2020, age 88.

For most of his life, Michael Gibson worked as a registrar of births, marriages and deaths in England. The “stickler for accuracy” signed off thousands of death certificates, but his own one is incomplete, says his daughter Cathy Gardner.

The 88-year-old, who had Alzheimer’s and lived in an Oxfordshire care home, developed a cough and fever in mid-March. By then, hundreds had been infected by coronavirus in the United Kingdom. But Gibson was not tested -- instead, he was given antibiotics.

When Gardner asked care home staff if anyone there had Covid-19, she was told a woman who tested positive in hospital had later died in the facility. Others had died, too, including the man in the next room, although it’s not clear if he died of Covid-19.

“There was no guidance to the care homes at all about how to protect other residents,” she said. “They were disregarded completely.”

On April 2, Gardner defied a nationwide lockdown to drive 270 kilometers (170 miles) from her home to see her father. She stood outside his window, watching as her dad dozed. “He had his eyes shut and he just looked comfortable and calm,” she said. “He loved classical music, so they had that on.”

He died the next day. His death certificate lists Covid-19 as a probable cause.

Gardner is taking the government to court, alleging discrimination and a failure to protect the vulnerable. The UK government denies it was slow to protect care homes, saying initial advice accurately reflected the situation and was later updated.

“It's very tough to need to keep talking through what happened to my father because it still is like picking the scab,” Gardner said. “I just know the support I've got from other bereaved families, and I’m doing this for them, too.”

Until March 13, the UK government’s advice was that people in care homes were “very unlikely” to become infected, as there was no coronavirus in the community. Hospitals sent Covid-19 patients back to homes that weren’t equipped to isolate them, despite these people being some of the most vulnerable. By mid-March, care home infections had soared. It wasn’t until mid-April that new rules stated all patients leaving hospital for care homes should be tested.

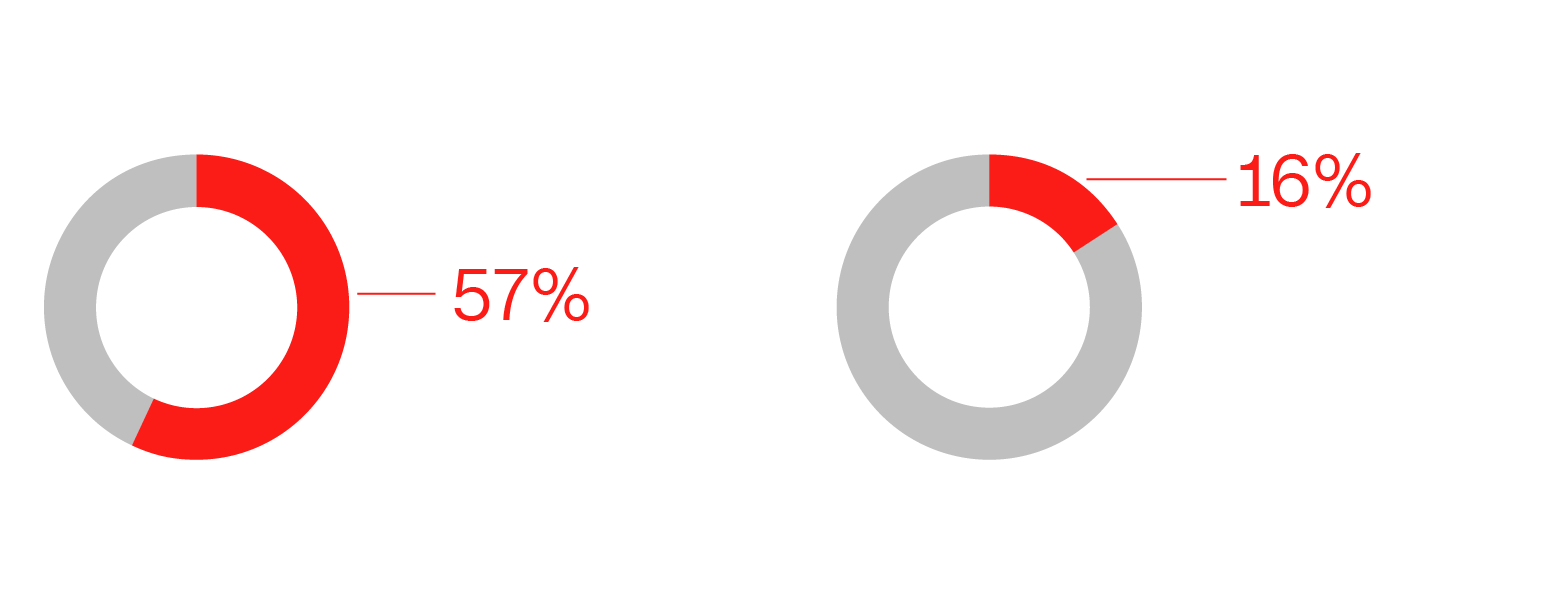

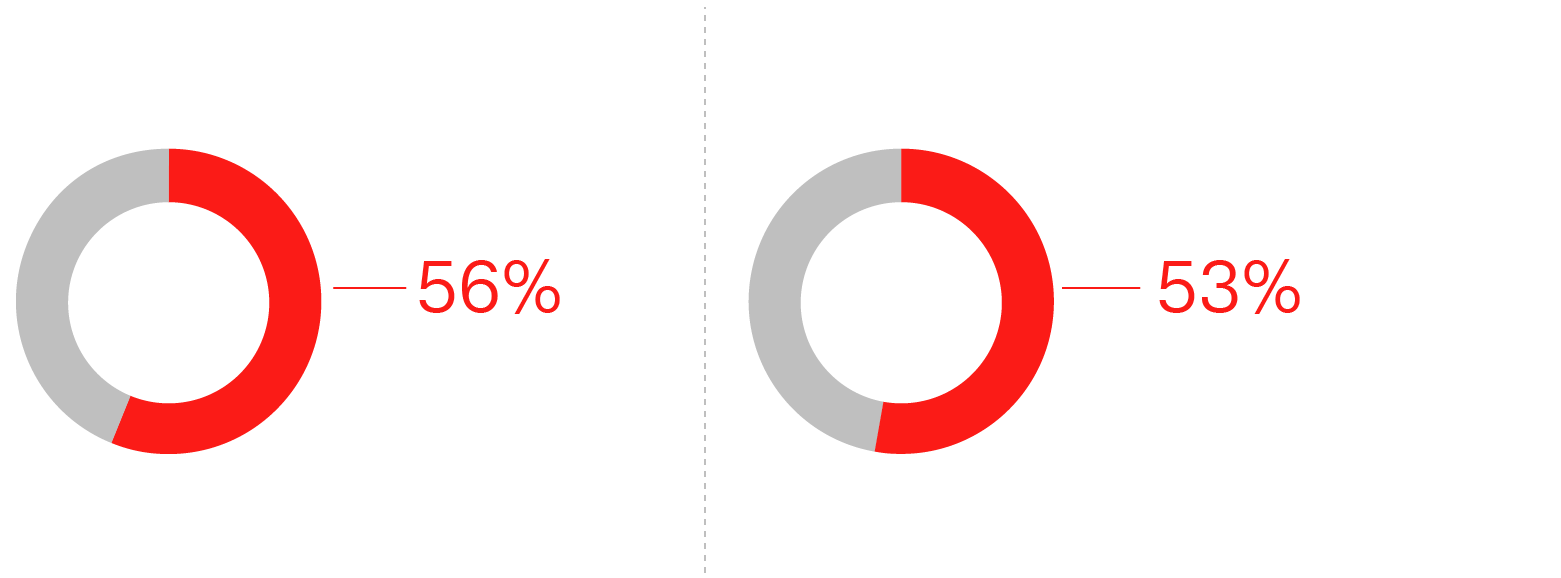

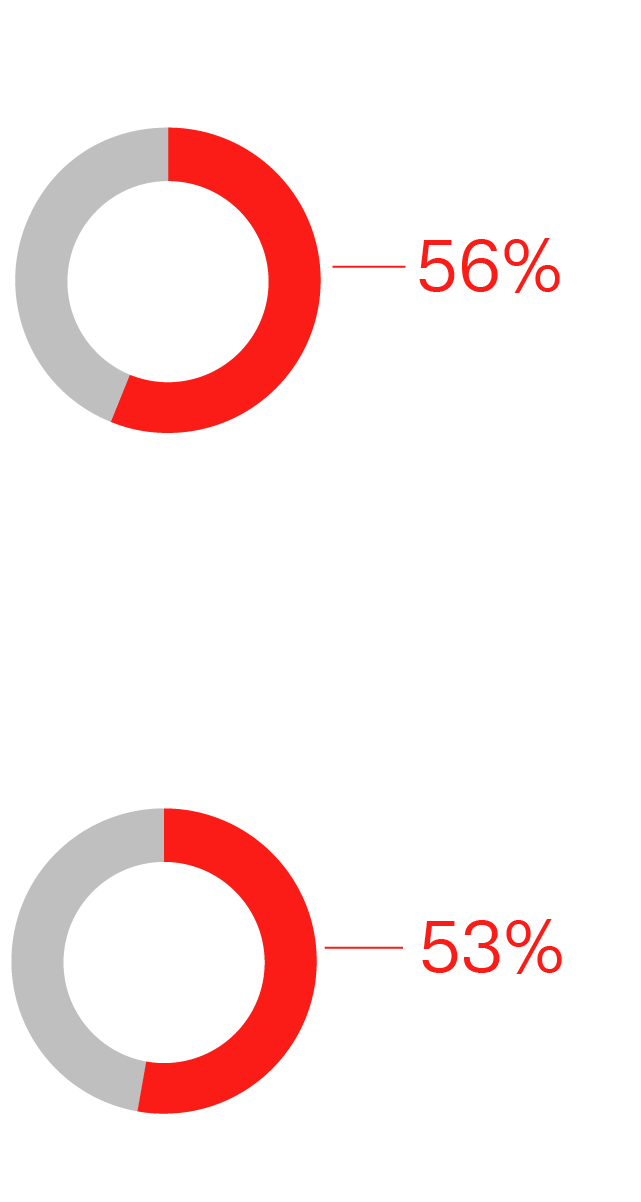

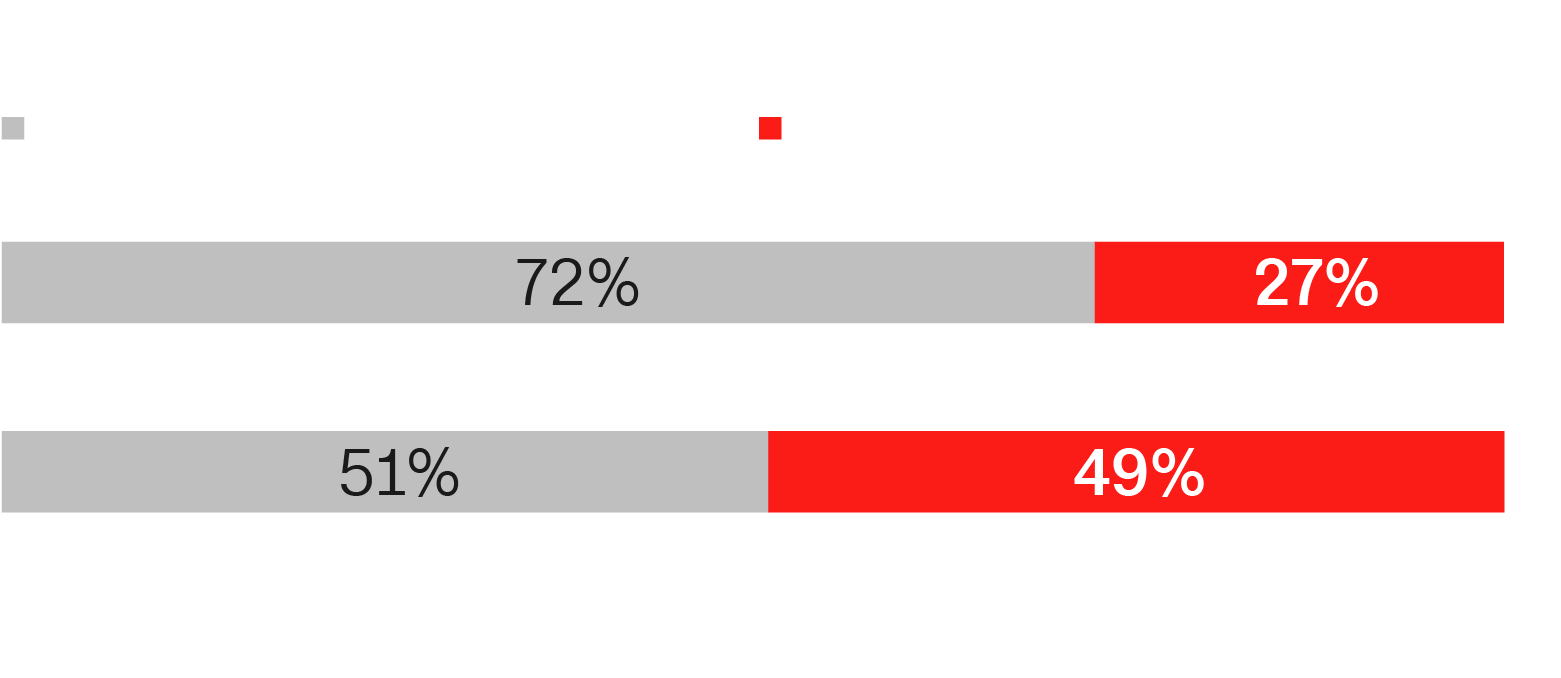

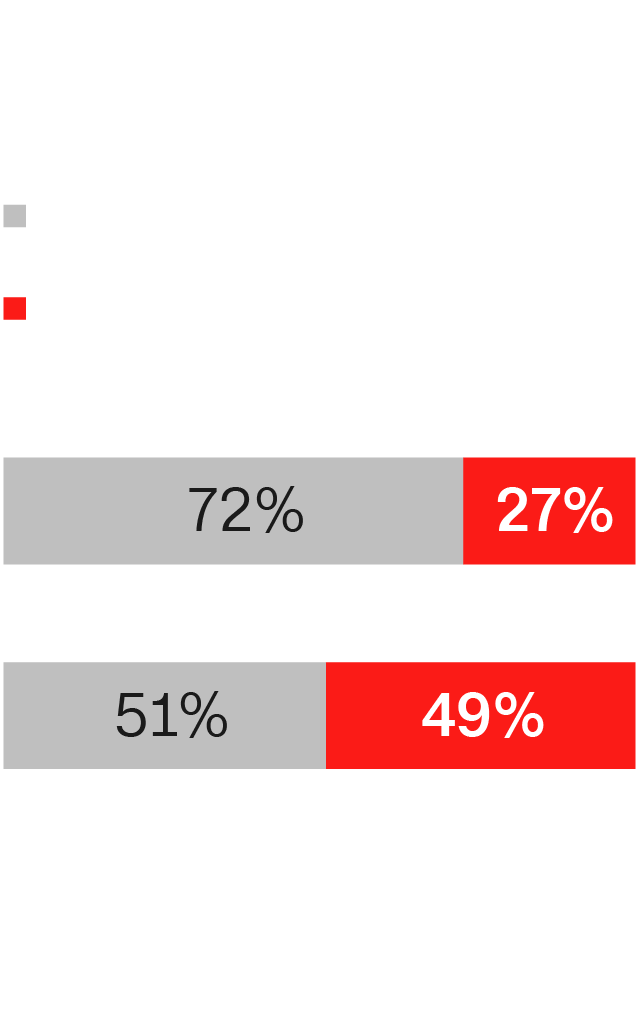

It was too late for many. Care home residents made up around 53% of the more than 36,000 Covid-19 deaths reported in England and Wales by June 12, according to government data. Worldwide, that figure is 47% on average, a study of 26 countries found.

Some people -- including US President Donald Trump -- have dismissed the virus as a disease that just affects the elderly with health problems, making some people wonder if he was implying that senior citizens are disposable. After 200,000 people died of coronavirus in the US, Trump erroneously claimed that young people were “virtually immune.”

Gardner and others believe the lives of the elderly deserve protecting.

“The steps that (the authorities) took have discriminated against the most elderly or vulnerable people in the population,” she said. “They've just failed in a basic duty to protect the citizens’ right to life.”

North America

deaths

When misinformation turns deadly

Credit: Courtesy of the Rose family

This is Richard Rose.

He died July 4, 2020, age 37.

Richard Rose served nine years in the US Army, including tours in Iraq and Afghanistan, but coronavirus was a battle he couldn’t win. The 37-year-old tested positive for coronavirus on July 1. “I’m officially under quarantine for the next 14 days,” he wrote in a post on Facebook.

Three days later, he was found dead at his home in Port Clinton, Ohio.

Although an autopsy wasn’t performed on Rose, Ottawa County Coroner Dr. Daniel Cadigan concluded that Rose had died of Covid-19 based on his positive result and his prior good health.

Rose’s family and friends remember him as a kind, friendly and caring man, who loved video games.

But by some online, he is being remembered for a different reason. On April 29, Rose posted on social media that he wouldn’t buy a mask. “I’ve made it this far by not buying into that damn hype,” he wrote. After he died, his post was shared widely online.

It’s not clear whether Rose changed his stance as he fought Covid-19.

“I’m out of breath just sitting here,” he wrote shortly before his death. Weeks later, Rose was still being attacked online for ignoring official health advice.

The science shows face masks work both to protect the wearer and to protect others from coronavirus, and everyone needs to wear one when around other people in public, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has said.

“We should still be compassionate whether we agree with someone’s beliefs or not,” Rose’s friend Nick Conley told CNN affiliate WOIO. “Someone has passed away and we should have some compassion towards that.”

In May, a conspiracy video claiming the pandemic was a hoax clocked up millions of views before it was removed by YouTube and Facebook. By then, the US had reported more than a million coronavirus cases. The immense appetite for a conspiracy video showed how widespread misinformation had become in the country.

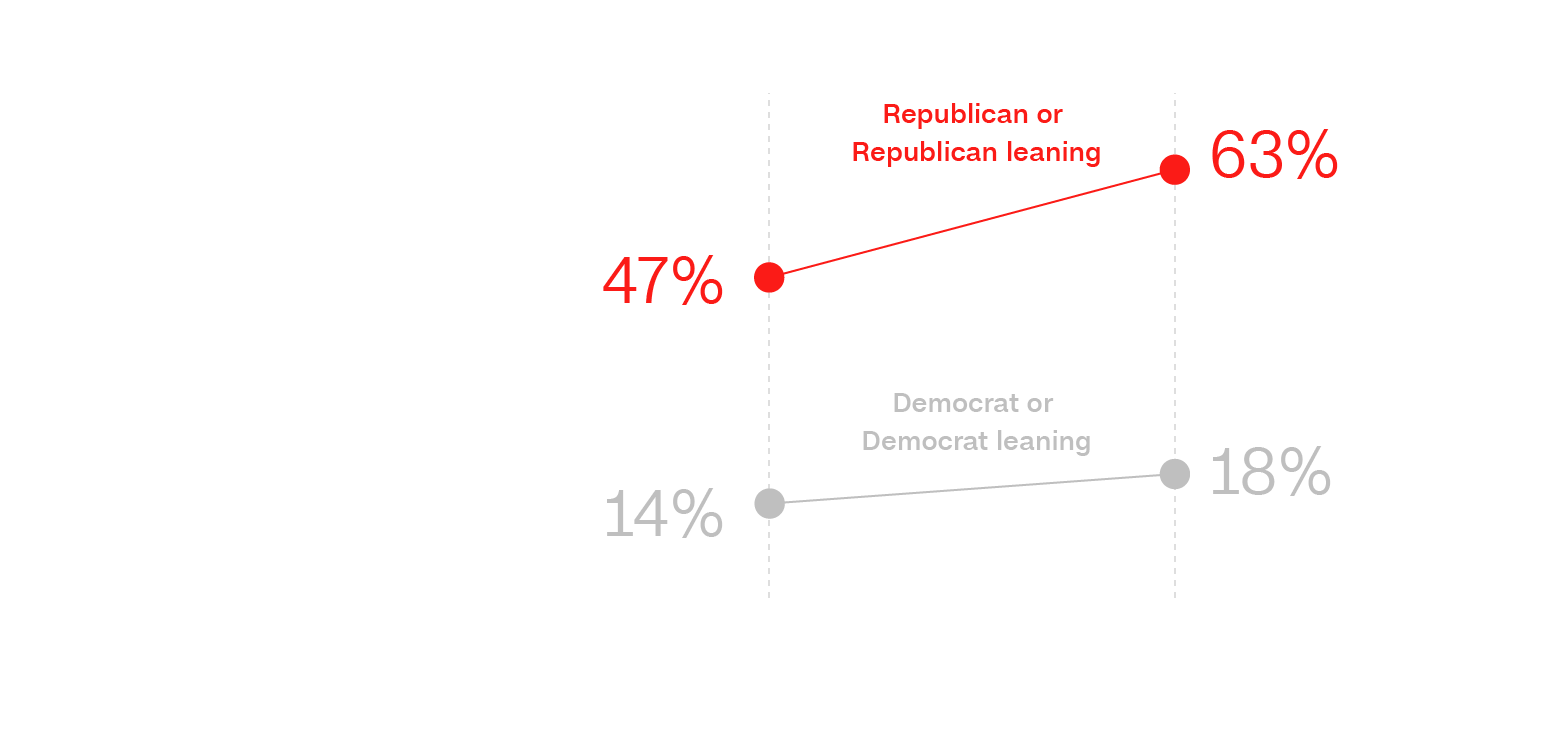

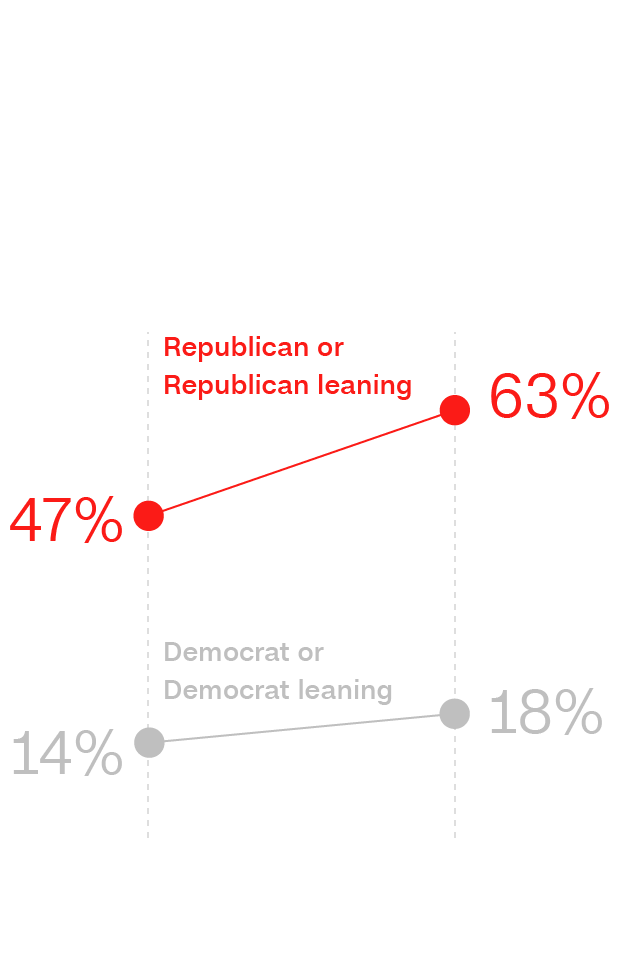

For years, President Trump had made statements not grounded in fact and undermined established news outlets. The pandemic raised the stakes.

At a time when scientific accuracy is crucial, Trump has consistently played down -- or flat out dismissed -- the threat of the virus, despite knowing how deadly it was. He has touted unproven drugs, including musing about whether disinfectants could be used to treat the virus in humans, asking whether there is "a way we can do something like that, by injection inside or almost a cleaning."

And it wasn’t until July -- by which time more than three million people had been infected by coronavirus in the US -- that the President finally wore a mask in public. Even now, Trump mocks Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden for wearing a face mask.

The coronavirus pandemic has demonstrated the real-world cost of a war on facts. Fake news has influenced elections and meant people are uninformed about the world. Believing in Covid-19 misinformation may have even cost lives.

Latin America and the Caribbean

deaths

Indigenous communities face a ‘genocide’

Credit: Family handout

This is Isarire Lukukui Karajá.

He died August 15, 2020, age 60.

It took four Covid-19 tests and a false pneumonia diagnosis before Isarire Lukukui Karajá was admitted to hospital in Brazil. Finally, on August 13, he tested positive.

The next day, his elder sister died of the virus.

As his condition deteriorated, aggravated by other health problems, his daughter, Tuinaki Karajá, pleaded for her father to hold on. “I told him: ‘Please, Dad, fight for your life.” Soon after Tuinaki returned home, the phone rang. Her father had died.

More than half of Brazil’s 800,000 indigenous people live in remote areas, including reserves. Many are far from hospitals, lack basic sanitation and are more vulnerable to disease due to isolation from the outside world. Even those in urban areas struggle to access public health care, have high rates of pre-existing health conditions and are often treated as second-class citizens.

All this has contributed to indigenous Brazilians being infected with coronavirus at almost twice the rate of the country’s general population.

Many of the 3,800 Karajá people, of which Isarire was from, live on the Santa Teresa do Morro indigenous reserve, in the state of Tocantins, according to independent non-profit Socio-Environmental Institute. Isarire’s father had been the leader of the reserve, and when he died, he passed that role to his son. On the reserve, he was known for his singing, for crafting delicate feathered traditional headdresses, and as someone you could ask for advice. In 2005, he became the first indigenous person to earn an accounting degree in Brazil.

“My father did a lot for the indigenous communities. He was a leader,” said Tuinaki. “He would say: ‘I do this because I like it, I want to see my people well.’”

When European colonizers arrived in South America 500 years ago, there were an estimated 11 million indigenous people. Within a century, the population had been reduced by 90%, mostly due to introduced diseases.

Coronavirus has sparked fears that a similar thing could happen again.

Even before the pandemic, in Latin America, indigenous people’s average life expectancy was 20 years shorter than the general population, according to the United Nations Development Programme.

As the outbreak took hold in Brazil -- which has the third-highest number of reported cases -- activists warned the government had not done enough to help people like Isarire. They said illegal mining and logging on indigenous lands -- which increased since Brazil's pro-development President Jair Bolsonaro was sworn in last year -- could bring the virus into vulnerable communities.

Indigenous people are so fearful of coronavirus that some launched a lawsuit to compel the federal government to establish safety measures. As Brazil’s top court handed down a partial victory in August, one judge said it wasn't an overstatement to describe the situation as a genocide. Indigenous communities in some countries, including Brazil, have protectively sealed themselves off.

The tragedy for indigenous people worldwide is that they have already lost so much to colonizers. Some tribes have been eradicated. Those left now face another threat.

"Those elderly are the keepers of knowledge, languages, traditions, festivities, rituals," Dinaman Tuxa, of Brazil’s Indigenous People Articulation, said. "We are losing much more than people, we are losing our culture, our nation.”

Africa

deaths

The wider cost of coronavirus

Credit: Family handout

This is Yassin Hussein Moyo.

He died March 30, 2020, age 13.

Yassin Hussein Moyo died after being shot on his family’s balcony in the Kenyan capital of Nairobi, watching police in the street below enforce a coronavirus lockdown. He was 13 and it was the third day of a nationwide curfew to stop the spread of coronavirus.

At the time, Kenya had only reported 50 cases.

Yassin’s father, Hussein Moyo Molte, was at a nearby friend's place watching the news and recalls hearing gunshots moments before his daughter called to tell him: "Yassin's been shot.” Police had been shooting to enforce the curfew. The teenager had been hit by a stray bullet in the stomach.

"My child was shot on the balcony at home, he wasn't even on the street," said Moyo. "I support the curfew but how the policeman handled it was very wrong."

Before his death, Yassin’s mother, Hadija Abdullahi Hussein, told her children not to fear police officers. But she says she has since lost all confidence in the force.

"Can I honestly tell them, policeman are good after policeman killed his brother? I cannot go back and tell them to trust the police,” she said.

The problem went beyond 13-year-old Yassin.

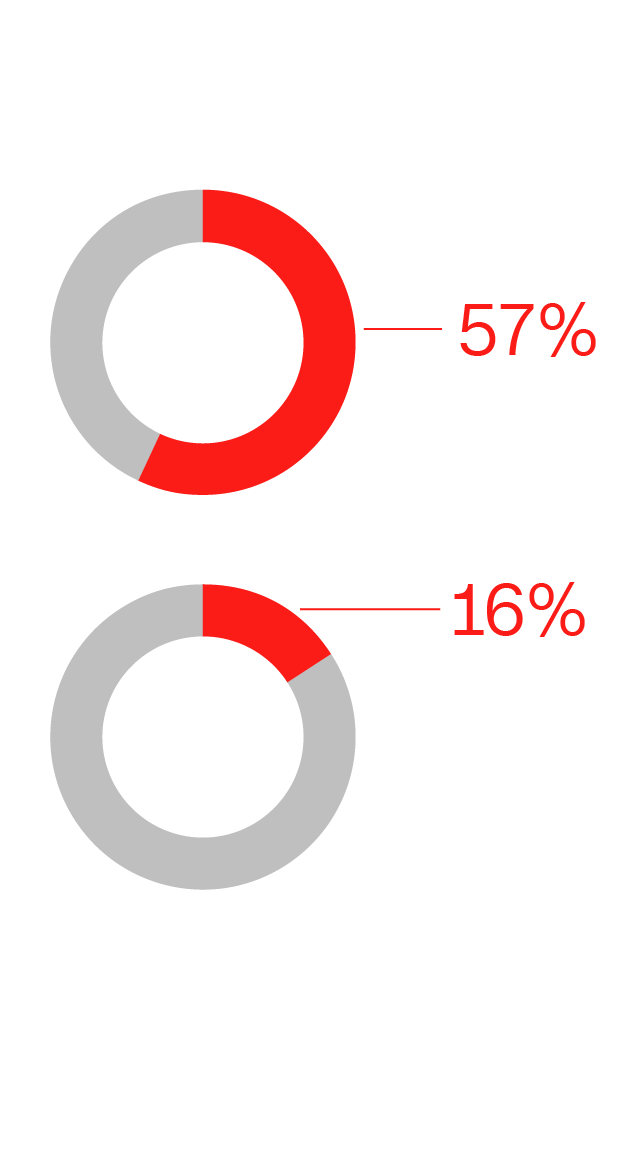

One month into Kenya’s nationwide lockdown, 14 people had died from coronavirus.

But by that point, 16 people had been killed by police officers while they enforced curfew rules, according to human rights group Amnesty International. The country’s Independent Policing Oversight Authority said in September that it is investigating the deaths of 20 people allegedly killed by police during the country’s ongoing curfew.

Disturbing videos on local media showed police violently tear-gassing, beating and forcing people to lie in tight groups on the ground in the coastal city of Mombasa. Kenya is now in its sixth month of nationwide curfew -- and there’s no indication of when it will end.

There have been instances of people dying as a result of police brutality in Kenya before, but the pandemic appears to have exacerbated the issue.

Kenya’s issue speaks to a broader crisis that’s playing out worldwide: The death toll of a million people doesn’t capture the true cost of coronavirus. Its victims extend far beyond those who are confirmed to have died from Covid-19.

That hidden toll is likely to grow.

By the end of the year, the United Nations World Food Programme estimates that as many as 12,000 people could die each day from hunger linked to the social and economic impacts of the pandemic, perhaps even more than are killed each day by the disease.

Those people will not be included in coronavirus statistics.

But they are part of the tragic cost of the pandemic.