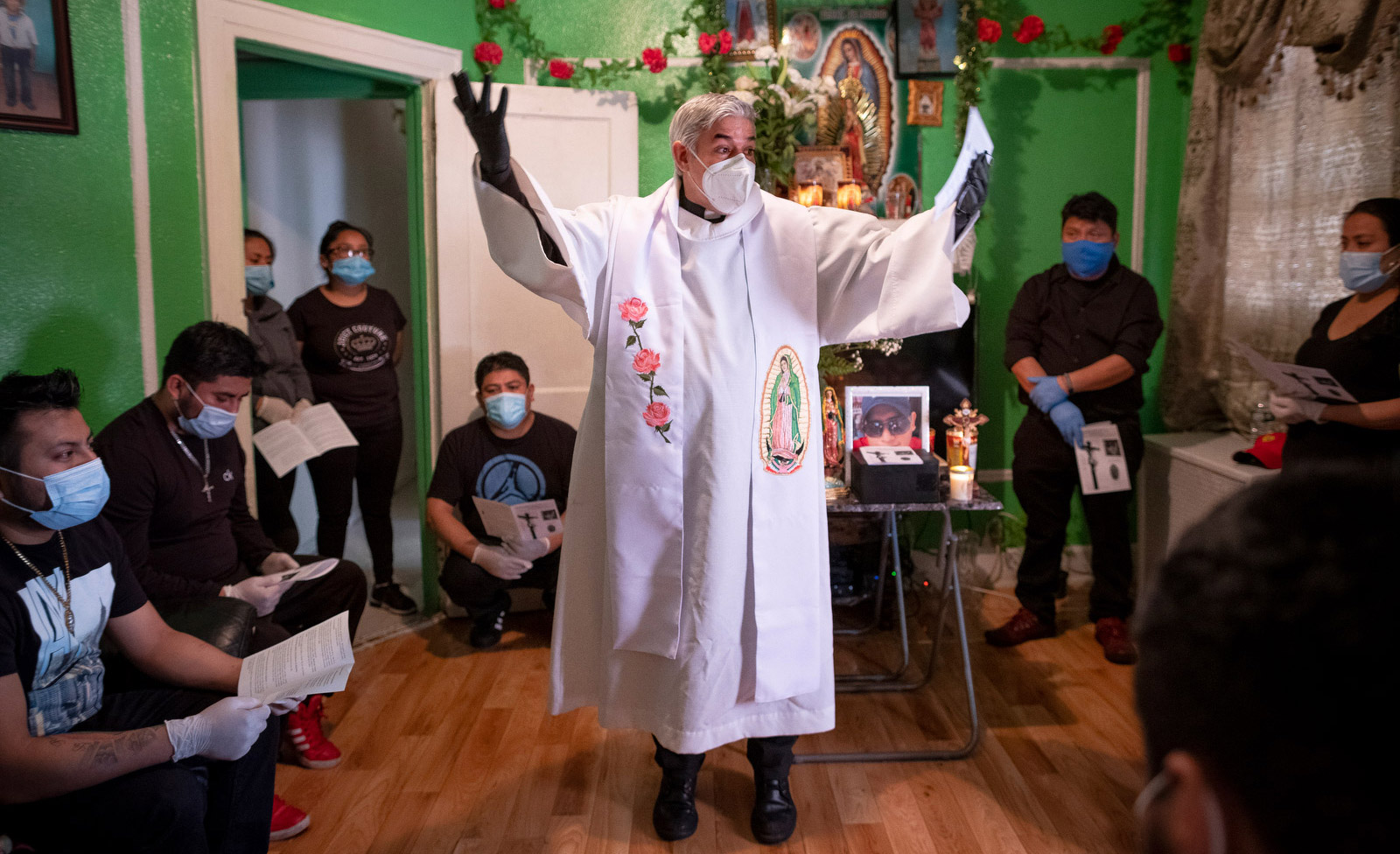

The Rev. Fabian Arias presides over a funeral Mass for Raul Luis Lopez in Queens.

This New York pastor says his parish lost 44 people to coronavirus

Story by Catherine E. Shoichet and Daniel Burke, CNN

Photographs by Ashley Gilbertson/VII/Redux for CNN

The Rev. Fabian Arias presides over a funeral Mass for Raul Luis Lopez in Queens.

Raul Luis Lopez is No. 33 on a list that keeps growing.

The 39-year-old restaurant deliveryman died last month in a New York hospital.

And at Saint Peter’s Church in Manhattan, he’s part of a devastating tally: Coronavirus Deaths from Our Parish.

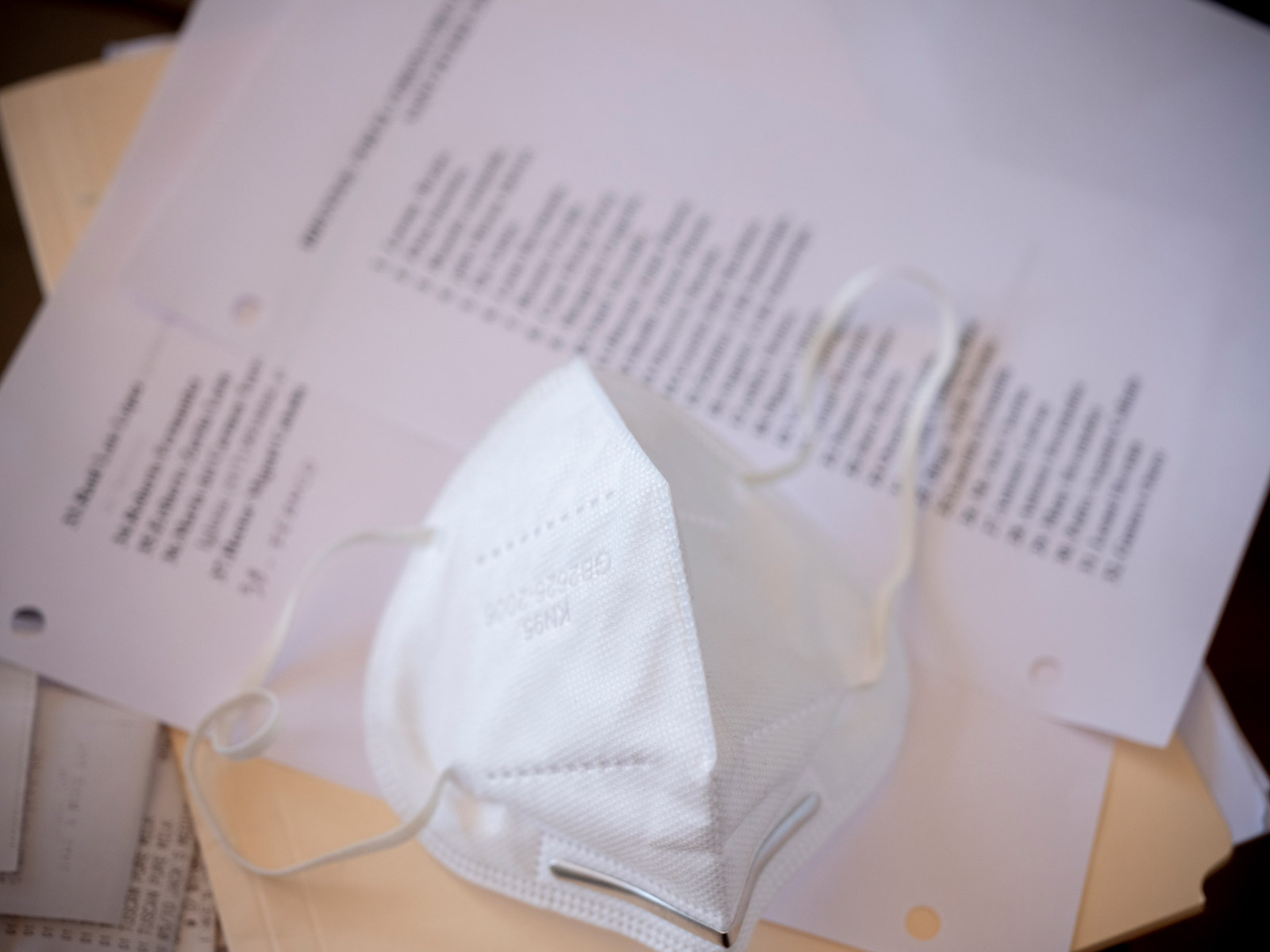

The list sits on the Rev. Fabian Arias’ desk, beneath the N95 mask he plans to wear to the next funeral he’s presiding over. There are dozens of names on it, and he fears soon there will be more.

Arias and other church leaders say the pandemic has killed 44 people from their parish.

Some were active members who regularly attended Mass. Others showed up sporadically for Holy Week, family baptisms or other special events. Arias views all of them as part of his parish. And he says the death toll in their church reveals a troubling reality about the way the coronavirus pandemic is cratering immigrant communities.

Inside Arias’ home an N95 mask sits on top of a list of parishioners who he says have died of coronavirus.

Church leaders provided a copy of the list to CNN, but asked for the full names of victims not to be printed to protect their privacy. CNN spoke with several family members of those who died and confirmed about a third of the names on the list with available public records, but was unable to confirm some deaths independently.

Of the deaths in the parish that church officials have logged, Arias says the majority — nearly 90% — are Latino. And many, he says, are undocumented immigrants.

“The virus installs itself more in the most vulnerable places, and so it infects the most vulnerable people. This is the problem. The virus does not discriminate,” he says. “We are the ones who as a society are discriminating.”

Leaders say coronavirus has devastated churches across the city

St. Peter’s sits above a subway hub and attracts worshipers from New York’s five boroughs, some of whom visit the church on their ways to and from jobs as deliverymen, waiters, construction workers and cleaners.

The congregation, which recently merged with a Spanish-language church, is about 50% Latino, according to church leaders. And it isn’t the only one that’s hurting.

Saint Peter’s Church temporarily closed its doors in early March as coronavirus cases in the city began to climb. Arias now conducts church services from the living room of his apartment in the Bronx.

Bishop Paul Egensteiner, who was elected to lead the Evangelical Lutheran Church’s Metropolitan New York Synod last year, said many majority-Latino congregations in the city are being devastated by Covid-19. In some, pastors report that 25-30% of the congregation is infected, he said.

The bishop told CNN he’s angered by Americans who argue the pandemic has been overhyped.

“You have to be in a very privileged place to be able to say that,” Egensteiner said. “You either have blinders on, or it’s an acute lack of awareness of how this virus is devastating communities.”

New York’s Latino population has been hit particularly hard by coronavirus. As of May 6, more than 5,200 Latinos in New York City have died of Covid-19, a higher death toll than any other racial or ethnic group.

It’s a trend public health officials and advocates have been warning of across the country as well.

As Arias heads to a funeral, he hands out protective masks to men passing by. “When I go in the street and I see people in my community that don’t protect themselves it troubles me a lot,” he says.

“We are dying at a higher rate because we have no other choice,” Frankie Miranda, president of the Hispanic Federation, told CNN. “These are the delivery food people, the people that are the day workers, the farm workers, these are people that are working in restaurants. They are essential services, and now they are not enjoying the protections that maybe in other industries people can have.”

Circles of friends and families are being hit hard. One reason, church officials say, is that immigrant workers often live in crowded conditions, making it easier for contagion to spread through the close networks. At St. Peter’s, church officials say one parish leader lost both her brother and father.

Egensteiner said Latino congregations across the city are facing the same crisis.

“When they’re able to gather again,” Egensteiner said, “congregation members are going to be shocked at who’s missing.”

Arias adjusts a cross in his living room, where he now broadcasts a biweekly Spanish Mass live on Facebook.

Reading the list of the coronavirus dead has become a new ritual

The list at St. Peter’s started in mid-March with just one name.

Now, the single-spaced list is so long that it stretches onto a second page. The grim ritual of reading the names out loud has become as much a part of the church’s biweekly Spanish Mass as reciting the Lord’s Prayer.

During each service, broadcast live on Facebook from Arias’ apartment in the Bronx, photos of the dead flash across the screen.

Behind each name, there’s a story.

There’s a beloved tango singer who enchanted audiences. There’s a construction worker who told friends and family he was scared to go to the hospital — and died at home, alone.

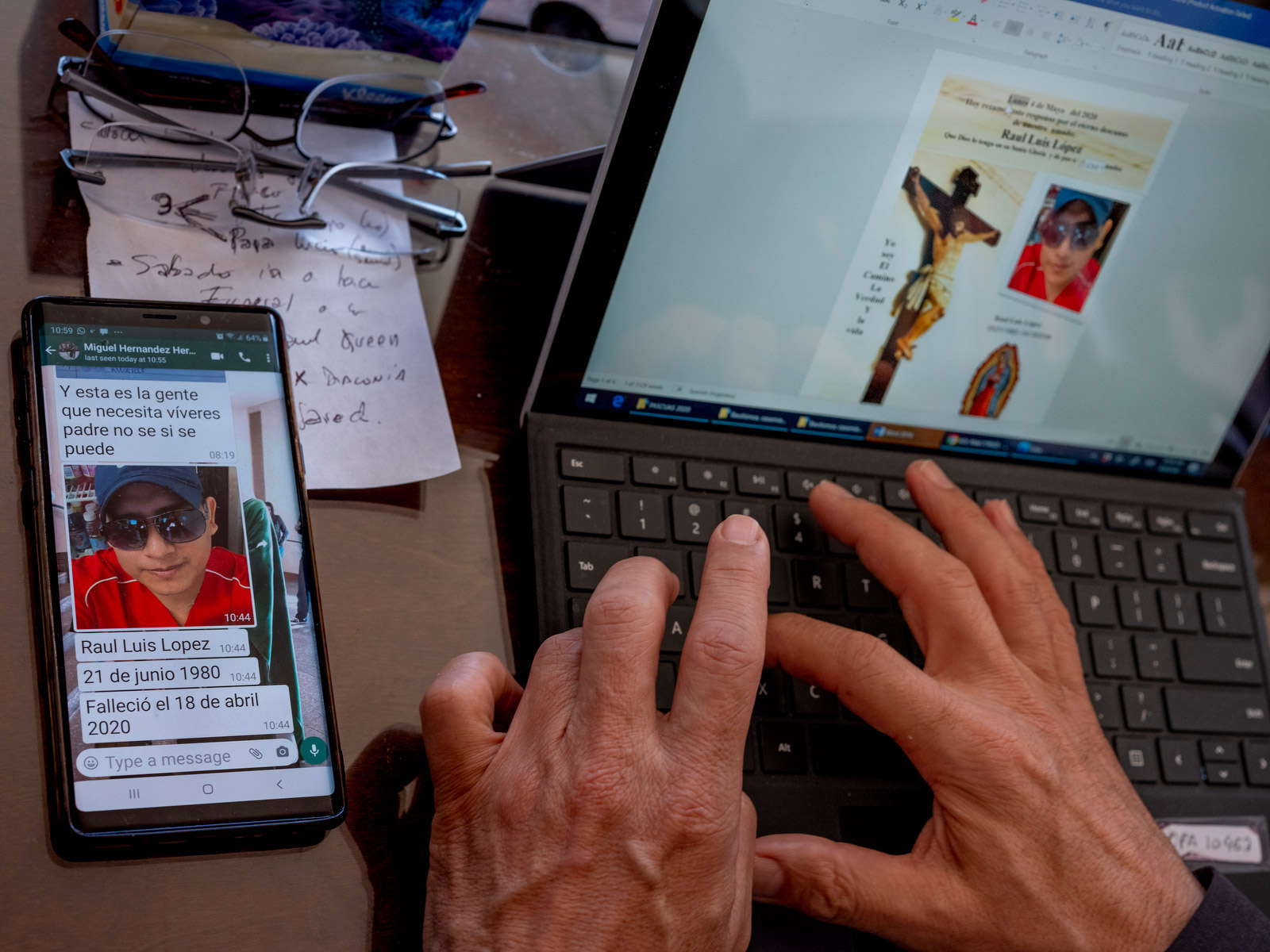

And then there’s Raul, the thirty-third name on the list, a restaurant delivery worker who suffered from diabetes, went to the hospital when he started feeling sick, tested positive for coronavirus — and never left.

Arias prepares the program for Raul Luis Lopez's funeral service. CNN has blurred part of this image to obscure an address.

“We thought he was going to be released soon. We don’t know what happened,” says his cousin, Miguel Hernandez. “We couldn’t go visit him. … It was horrible.”

Hernandez says the hospital called him to tell him his cousin had died, and that Covid-19 was the cause of death.

He says hearing his cousin’s name read on the long list at Mass brings him comfort — but also breaks his heart.

“There are so many people,” he says, “who are in the same situation that we’re in — suffering.”

The church has sheltered people from fear

The original St. Peter’s Lutheran was founded in 1861 by German immigrants, who worshipped above a feed store in midtown Manhattan. The church later sold its land for $9 million to a precursor of Citigroup, which built both an office tower and the modern triangular church that now rises from the corner of 54th Street and Lexington Avenue.

As Lutherans moved out of the city and the congregation dwindled, St. Peter’s reimagined itself less as a sanctuary for worship than a ministry to the creative and chaotic city that surrounds it. The church hosts art galleries, jazz vespers, programs for the sick and food pantries for the homeless, as well as legal clinics for immigrants.

Arias packs his car to head to a memorial service. He has presided over eight funerals in the past week.

And as the Trump administration has intensified its immigration crackdowns in recent years, Arias says many have come to the church because of legal clinics offered there. Arias, who leads Spanish-language services at Saint Peter’s, says immigrants from at least 14 different Latin American countries consider the church a spiritual home.

“People were searching for protection. … They want to baptize their children, communion, confirmation, all the sacraments. They’re drawn in by faith,” he says. “But in the last few years, fundamentally they’ve been drawn in by fear.”

Arias, who made headlines when he became the legal guardian for numerous immigrant children to help them stay in the United States, says the congregation’s immigrant members aren’t strangers to dealing with disasters. Superstorm Sandy destroyed some of their homes in New York. And some have seen earthquakes devastate parts of their home countries.

But nothing, Arias says, has shaken them like this pandemic.

At home, Arias makes a homemade remedy of ginger and garlic to boost immunity while a mask is sterilized on the stovetop.

“People are afraid,” he says, “and it’s even sadder for these people because the majority of them lost their jobs.”

Restaurants shuttered. Construction sites closed. Long-time employers let go of housekeepers in a span of seconds.

“They live off of this money day to day,” Arias says. “Now they don’t have it to feed their children.”

So Arias has been leading a push to distribute donated food to hundreds of families. And in sermons, he tries to offer comfort to his congregation.

“When we walk in the darkness of confusion, of hopelessness, friends, Christ offers himself to us as a light,” Arias said in a recent Wednesday night broadcast.

But even for Arias, the darkness is impossible to ignore.

A statue of the Virgin Mary sits in the corner of Arias’ apartment.

In the past week, he says he’s presided over eight funerals, including four for people connected with the parish.

“Every day, two more are dying,” Arias says.

That leaves little time to grieve, he says, or to absorb the magnitude of what’s happening.

“You feel as though if you stopped to think about it, you wouldn’t be able to continue,” Arias says.

Today he’s presiding over another funeral Mass.

A living room funeral, with masks and gloves

Arias hands out masks and gloves as soon as he steps foot in the candle-lit living room. Then he asks everyone to stand as far apart as they can.

Normally they’d be inside their church. The pews would be packed. He’d hug the mourners before the service started so they’d know they weren’t alone.

Arias arrives for Raul Luis Lopez’s funeral. Everyone in attendance was given masks and gloves.

But the building in Manhattan where St. Peter’s normally holds its Masses has been closed since early March. Raul Luis Lopez’s funeral is taking place at the home in Queens where the delivery worker lived.

It’s a small gathering for immediate family, and the first funeral Arias has done in a private home. And today he is just as focused on protecting the living as he is on leading prayers for the dead.

In addition to the gloves and masks, he’s brought disinfectant spray for the communion plate.

Today we ask you for the eternal rest of our beloved Raul Luis Lopez. Bless these ashes that were part of his mortal life here on earth.

Arias stands in the center of the room. A small black box holding Lopez’s ashes sits on a table nearby, surrounded by candles, in front of a big-screen TV.

Raul Luis Lopez’s funeral, at the house in Queens where the delivery worker lived, is the first Arias has presided over in a private home.

Also bless his loved ones who are here today and this family of faith that is participating today in this prayer for the dead in this place.

This place is a living room with bright green walls bearing school achievement certificates. It is a neighborhood where many Mexican immigrant families live. And it is a community where Arias knows many people in the shadows are suffering.

Let this peace that only you, God of life, can give us, remain in each one of us.

Arias peers out over the top of his surgical mask and scans the room as he speaks. He makes an effort to look each person in the eye.

He can’t hug them, but he wants them to know that no matter what happens next, he will remain with them, too.

Mourners gather for a meal after Lopez’s funeral. More than 5,200 Latinos in New York City have died of Covid-19, a higher death toll than any other racial or ethnic group.

Ashley Gilbertson contributed to this report. He is a photojournalist based in New York and represented by the VII Photo Agency.

Photo editor: Brett Roegiers