Frozen in Time Forty five years ago, eight Soviet women climbers were pinned on top of a high mountain in the USSR in the worst storm in 25 years.

It was June 1974. The Cold War was verging on détente, though the Watergate scandal overshadowed the Moscow Summit between President Richard Nixon and his Soviet Union counterpart, Leonid Brezhnev.

A month later, thousands of miles away in Central Asia, close to the Himalayas in the shadow of Peak Lenin, another meeting took place between an American and a Russian.

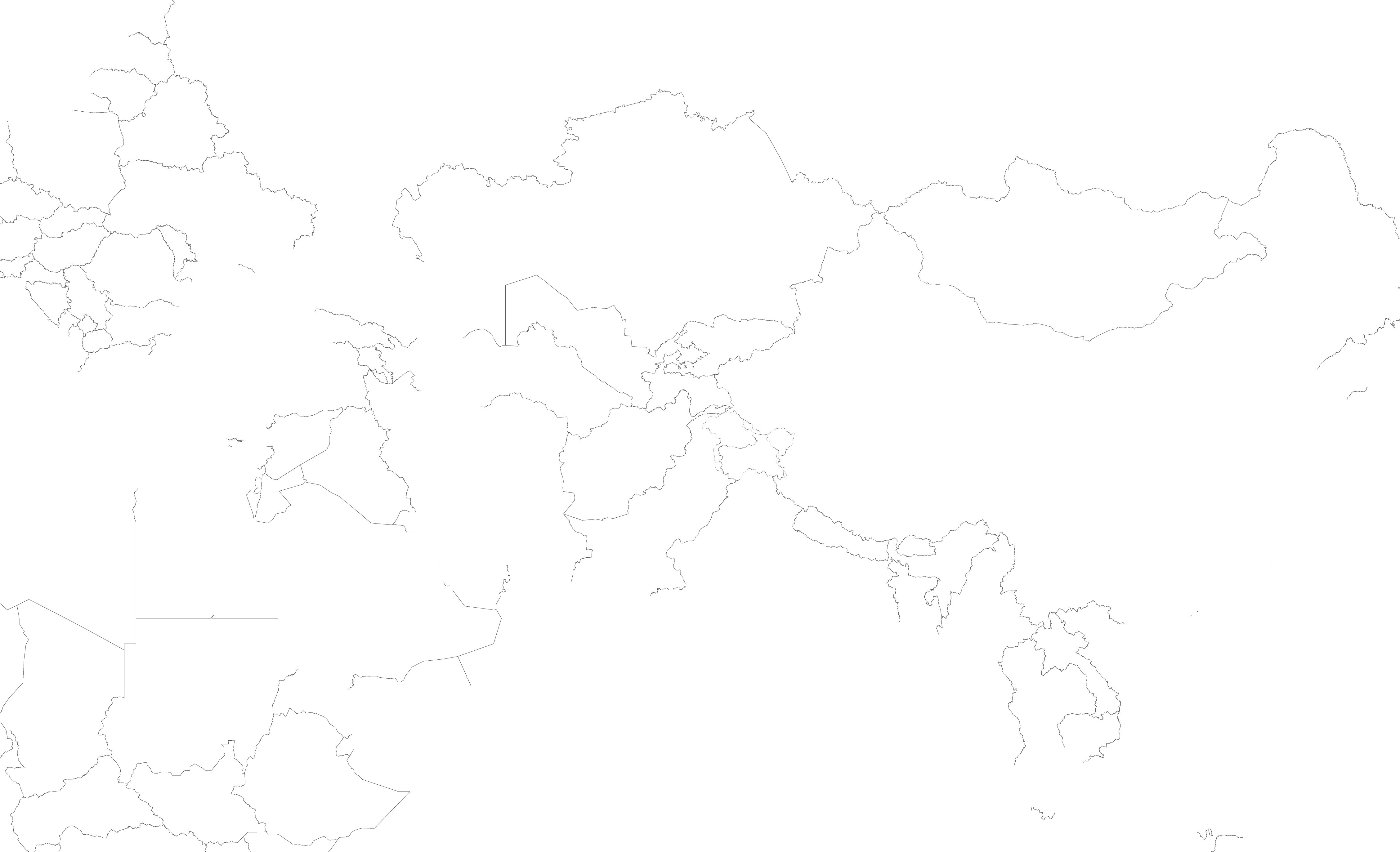

Soviet Union

Iran

India

China

Soviet Union

Iran

Saudi Arabia

India

China

Mongolia

The map reflects modern-day geography; the Soviet Union border is based on the borders of the countries that were part of the USSR. Map credits: maps4news.com/©OSM, Encyclopedia Britannica

In 1974, 170 climbers from a number of countries occupied a huge mountaineering camp in the southern part of the Soviet Union, on the border of what is now Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

They camped in the Pamir Mountains, or Pamirs, a range with some of the world's highest mountains.

Many would climb or attempt the 7,134 meter (23,406ft) Peak Lenin. While not considered steep or technical, it is high and subject to severe weather.

Molly Higgins first saw Elvira Shatayeva as she came around a bend in the High Pamirs mountain range, sometimes known as “the roof of the world.”

An Outward Bound instructor traveling the Colorado Rockies, living out of a faded white sedan, Higgins had been asked to a month-long international mountaineering gathering hosted by the Russians.

Nineteen Americans, including two women, attended as part of the 1974 American Pamirs / USSR Expedition. Higgins, then 24, was a last-minute invitee when organizers, many unsure or uneasy about quite where women fit in on expeditions, realized that one woman did not seem like enough.

"I was ambitious and very self-confident, and I thought I was very strong,” recalls Higgins, now a clinical laboratory scientist in Whitefish, Montana.

She was with a crew carrying loads up to Camp II -- Crevasse Camp -- toward Krylenko Pass on the shoulder of Peak Lenin, the country’s second-highest mountain, when an earthquake shook the slopes.

Higgins remembers a creaking sound. Then an avalanche roared overhead, launching off the top of an ice tower above camp.

The avalanche darkened the air, scattered gear, and partially buried one person, with at least two others jumping into the crevasse to escape. Four among the crew had descended earlier to resupply, and for hours those in both groups dreaded that the others had died.

Yet all had survived, though in the lower group Allen Steck, a pioneering climber from Berkeley, California, was buried up to his neck. The two groups joyfully reunited at Camp 1, on the Krylenko moraine, and retreated, shaken, to base camp in an alpine meadow.

Some 170 climbers from 10 Western countries occupied a huge mountaineering camp, with another 60 Eastern European and Russian climbers and officials across a stream.

This was the first major American expedition allowed in the Soviet Union, which has some of the highest and most remote mountains in the world. The gathering was held to showcase the region and the skills of the host climbers and, it seemed, develop relationships with Cold War rivals. It was seen as a means to bring up young mountaineers and foster mountaineering relations between countries.

Meet the climbers

No one could ever have imagined how many things would go wrong that summer, events rained down by the skies and upthrust by the earth, nor the heroics that would ensue.

Yet the story of one of the greatest disasters in all of mountaineering has been almost completely lost.

Even many non-climbers know of Everest disasters and who Alex Honnold is. Yet almost no one today, climbers included, has ever heard about what befell eight Russian women in 1974. A Google search turns up nothing about the 45th anniversary last year.

“He is injured!”

Describing the retreat after the calamitous avalanche, Higgins says: “We came down through these huge boulders, around a corner, and there, standing up, was this absolutely gorgeous, bright-blue-eyed, muscular, bossy hottie on a boulder, and she’s got about four Russian guys around her, and she’s ordering them around.” The woman was in her mid-30s.

Spotting that an American, Mike Yokell, was limping -- after jumping into the crevasse beside Camp II to escape the avalanche -- Shatayeva called out, “He is injured! Take his pack!”

Shatayeva then wheeled around, looked at Higgins, and said in deep, careful tones, “I am Elvira Shatayeva. I am Master of Sport. What are you?”

Master of Sport was the top credential in any sport in the status-aware Soviet Union, even more impressive when attained by a woman.

Higgins recalls: “I thought it was great. I didn’t want to be bossy like that, but here was a woman who really was capable. I wanted to be like her, that strong and that experienced. She was a heroine, right there.”

In an era of relatively few women climbers, Higgins had never met one who was the kind of climber and mountaineer she wanted to be. It was to be the young American’s only interaction with Elvira.

“I knew right then that it was a transforming moment.”

Awkward dynamic

Arlene Blum, a biophysical chemist and environmentalist from Berkeley, California, had applied to the American Alpine Club to join the American contingent, but was declined.

However, some Swiss climbers, through an international women’s climbing club, brought her in on their invitation to be part of a women’s team. The situation created an awkward dynamic when Blum, 29, arrived in the Pamirs and entered the jam-packed mess tent.

As she told the story in her memoir “Breaking Trail,” she approached the crowded American table, but was ignored.

She wrote, “I stood amid the roar of voices, holding my bread and caviar and wishing I could disappear. Blessedly, a striking blonde Russian woman waved me over to her table.”

Shatayeva introduced herself and welcomed Blum. As they talked, she told Blum that most Soviet men thought a women’s team would never succeed on the 23,406-foot Peak Lenin — her group’s aim.

“We plan to be the first women’s team to do it,” said Shatayeva. “Or maybe your group will be.”

Blum, put at ease, said, “Maybe we could all climb together.”

“That is impossible” was the swift reply. Blum could only surmise that the Soviets wanted the first women’s team to be their own. Shatayeva told Blum the larger plan: that the eight women would climb the peak by the Lipkin Ridge on the northeast side and descend the northwest ridge toward the smaller Razdelny Peak. Theirs would be the first traverse, by men or women, of the peak. They were to bivouac, or make a temporary camp, on top.

“Soviet women are very strong. We have collective spirit and we work together.”

“We will succeed,” she told Blum. “Soviet women are very strong. We have collective spirit and we work together.”

Blum today recalls Shatayeva’s “warmth and energy.”

“We shared a common goal of giving women the chance to climb high mountains and were so happy to be in this camp with other climbers who shared our delight in the mountains,” Blum reminisces.

She remembers feeling some concern about the ambitious plan to traverse Peak Lenin.

“This was in the days of the Cold War, when we were in competition with the Russians. I looked at their inadequate tents with button closures and [their] old-fashioned boots and thought how the Russian technology seemed to be going more into space than the mountains.”

“Cat-like blue eyes”

Christopher Wren, a climber and Moscow correspondent for the New York Times (he was to become bureau chief in December of that year), met Shatayeva in base camp early in the meet, which commenced in mid-July.

A passage (later anthologized) from his book “The End of the Line,” about his years in Russia and China, read: “A striking blonde with high cheekbones and cat-like blue eyes, she had come there to lead a team of the Soviet Union’s best women climbers in an assault on Lenin Peak.” Chatting with her over tea, he sensed a “steel core” beneath the surface.

The next time Wren saw Shatayeva was as he and two friends approached the top of Peak Lenin after a storm-blasted, two-night bivouac 1,000 feet below the summit, and spotted a splash of color, a blue jacket in a snow hollow.

“Someone,” he would write of that confused first impression, “seemed to be lying asleep in the bright sunshine.” He thought, An odd time for a nap.

Disciplined unit

Robert “Bob” Craig (who died in 2015, at 90), deputy leader for the American team and author of the subsequent expedition book, “Storm and Sorrow,” wrote: “For the most part, the women remained across the creek in the ‘Soviet Nationalities’ camp. They made several practice climbs, and we observed them a couple of times doing calisthenics in front of their tents.”

The women, whom he described as aged 22 to 35, appeared to be “very serious … still they sang songs together, and not infrequently we would hear their excited chattering and their laughter tinkling like bells across the valley.”

Elvira’s husband, Vladimir Shatayev, later wrote in his memoir, “Degrees of Difficulty,” that the women operated as a disciplined yet congenial unit. “Not once did we hear words of argument or contention.”

She told him, “You should read the minutes” of their meetings. “You men have never dreamed of such openness.”

Shatayeva had already organized the first all-women’s ascent of a 7,000-meter peak — Peak Korzhenevskaya (7,105 meters) -- in Tajikistan in 1972, and led a traverse of the double-summitted Ushba (4,710 meters) in Georgia the following year.

Two nights before the women set out, the American climbers Jed Williamson and Peter Lev strolled over to their camp to say hello and good luck. In a country of regulations, as Williamson, now a retired college president living in Hanover, New Hampshire, says, “It was the first time they were allowed to go without the company of men.” Four of the women had climbed Peak Lenin with males.

Dire natural circumstances

But no one could control weather or geology. The whole Pamirs meet was plagued by snow, rapidly developing avalanche hazard, an earthquake that shook avalanches down (with two more quakes later), and the worst storm seen in the region in 25 years.

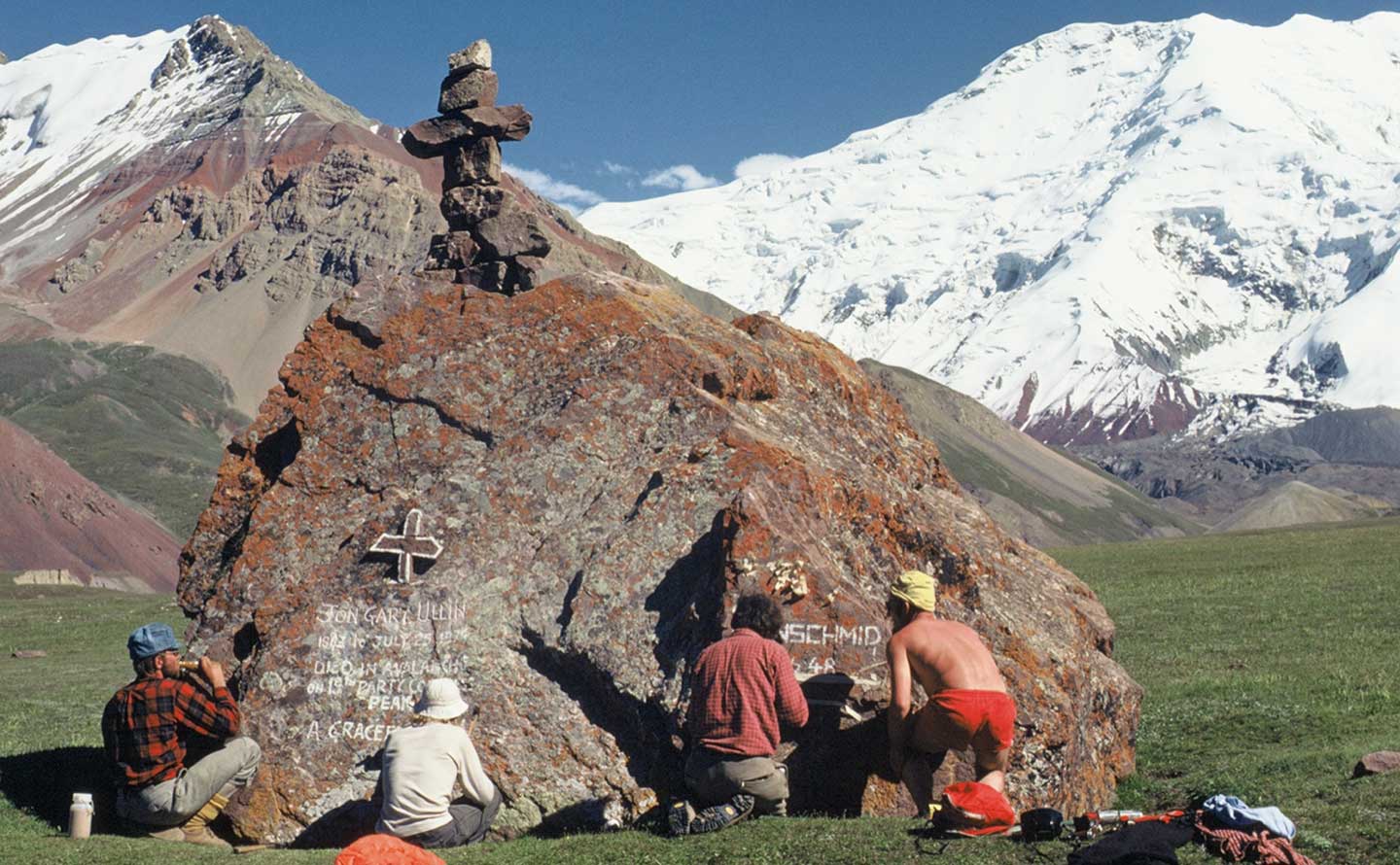

At 1:00 a.m. on July 26, barely more than a day after Higgins and her group returned from Krylenko Pass, four climbers forging a new route on the north face of Peak of the 19th Party Congress (or Peak 19) were hit by an avalanche as they slept. Craig, the deputy leader for the American team, and his tent mate, Jon Gary Ullin, were buried. Ullin, 31, an affable and humorous airline pilot from Seattle, was crushed.

Their friends John Roskelley and John Marts had excavated both and tried to resuscitate Ullin when yet another avalanche hit, enveloping Craig again and sweeping away the tents and equipment.

Roskelley, Marts and Craig were then stranded in a snow cave for two days and dropped supplies in a superb collaborative helicopter rescue effort by the Soviets, who allowed Lev a key role as “drop person,” in which he had experience.

Lev, an avalanche forecaster and heli-ski guide, recalls the Russian helicopter being extremely powerful. “I was in the large open door, just hanging onto something,” he says, “and was able to get the drop ‘on their doorstep’” from about 50 or 75 feet above.

“The pilot deserves real credit.”

Five climbers who were not part of the meet and known to visitors only as “the Estonians” went missing on the East Face of Peak Lenin. Three were found to have died in an avalanche, and the other two were rescued and survived. Many accounts incorrectly say all five died.

For most in the assemblage, objectives changed in accordance with the conditions; although Roskelley and Jeff Lowe returned and completed the line up Peak 19, other climbers converged on the “standard” routes.

Meanwhile Higgins, while feeling lonely and isolated among the mostly male contingent, ended up in a group of four (herself; the expedition leader, Pete Schoening; Chris Kopczynski; and Frank Sarnquist) that climbed Peak Lenin via the Razdelny ridge on August 3.

The other American woman on the meet, the much-respected Marty Hoey -- who tragically died on Everest eight years later – also climbed the Razdelny side, with Lev, Bruce Carson and John Evans on August 4. Williamson started with them but, feeling ill, turned back.

While the mountain is not considered steep or technical, it is big and high and beset by challenging weather conditions, with sections of moderately steep ice, especially high on the Lipkin side.

Elvira Shatayeva and the Russian women made final preparations for Peak Lenin climb.

July 30 - The Russian women’s team left Base Camp for Camp I.

July 31 - The team took the Lipkin route and proceeded toward the summit without any problems. On August 3, Shatayeva called a rest day.

August 3 – An American team of climbers behind the Russian women reported: “Cloudy weather today and we have route-finding problems getting over to Camp III in whiteout conditions.”

August 4 - A major storm was forecast, and organizers recommended all climbers descend. The Russian women were seen walking in a line perhaps 400 feet below the summit.

August 5 - The Russian women’s team radioed from the summit. August 6 - The women tried to descend but only managed a few hundred feet. Speaking to base then and August 7, they reported their struggles. Their final transmission came through at 20:30.

August 8 - The storm was over. From their final camp, located about 400 meters below the summit, the American team set out for the summit with no idea of the events that had occurred above.

“Our summit day was so hard I couldn’t believe it,” Higgins says. “The altitude … I did some collapsing. It was a really humbling experience. I was very proud of it and so glad it was done.”

Jeff Lowe, a standout young climber (who died of natural causes in 2018), would much later post in an online thread: “[S]ome of the guys on the trip gave her a hard time, claiming she didn't have enough [expedition or alpine] experience to be there. Molly proved them wrong, though -- pulling her own weight and generally comporting herself in a competent manner.”

On August 3, Steck moved up on the Lipkin side with Wren and Jock Glidden. Steck wrote in his diary, as reported in his 2017 memoir, “A Mountaineer’s Life”: “Cloudy weather today and we have route-finding problems getting over to Camp III in whiteout conditions. Our altimeter tells us we are at about 5,800 meters,” or 19,030 feet. On August 4, the three took a layover day.

The Americans’ radios had been impounded in customs, so Steck’s group had only a weak radio on loan from the Soviets, and all countries had been put on different frequencies. That day, a major storm was forecast, and Vitaly Abalakov -- Master of Sport for mountaineering in the whole country (who died in 1986) -- recommended that all climbers descend to base. Steck’s group never received the message, nor did Richard Alan North of Scotland.

“Our summit day was so hard I couldn’t believe it.”

From July 31 to August 3, North, a biomedical scientist now retired and living in Niwot, Colorado, and teammates moved up a “new though not particularly difficult” route to join the Lipkin route.

On August 4, by then climbing alone, North cut steps, as was commonly done in the era, in the steepening ice -- tedious, tiring work accompanied by altitude-induced hallucinations. He reached the top and then descended, slipping a few times and gripping his ice axe for self-arrest on the hard snow. At the foot of the steep section, perhaps 400 feet below the summit, he met the Russian women, walking in a line.

It was windy, with visibility “just a few meters,” he says.

They exchanged greetings, and North was later to recreate the scene in Summit magazine, writing: “They are moving slowly up but in high spirits.

“‘You get a bit short of breath up there,’ I remark jokingly. But the humor is lost on them.

“‘Ah! We are strong. We are women,’ they reply.”

North descended, passing some Soviet men who summited behind him and later joined his descent.

He believes the women climbed the steep icy section and camped that night on the eastern edge of the summit ridge, before moving to the summit the next day.

On the morning of August 5, on the somewhat more straightforward Razdelny side, a Soviet climber came to Blum’s tent at Camp III, the top camp, with a message from base saying, “A storm is predicted. Do not try to climb.”

Still, the air remained calm and fairly clear, people had come a long way and were in position, and some chose to try. Blum, Heidi Lüdi and Eva Isenschmid of Switzerland started up, though the latter two carried extra gear and planned on a possible bivouac, so Blum hastened ahead, with a turnaround time in mind and hoping to beat any weather.

Nearing the top when the storm hit shortly before noon, Blum retreated, soon fighting the wind and blizzard. She was fortunately joined by Williamson, who had started up for the summit again, also with a firm turnaround limit and an eye on the weather. He had retreated from very high -- the summit plateau at 22,800 feet.

Williamson broke trail and urged Blum on when she sat, exhausted. On the way down the pair saw Blum’s two teammates and a Bavarian woman friend and entreated them to descend as well; Isenschmid, a 23-year-old photographer and artist whom North calls a “gentle soul,” was to die in the storm the next day despite strenuous rescue efforts from her partners and French, German and American climbers.

Meanwhile, Steck, Wren and Glidden hiked up to just below the major ridge and in wild storm conditions stopped and camped at 22,000 feet, their Camp IV, the final one.

The Soviet women’s team summitted late afternoon on August 5, carrying full loads (climbers not on a traverse can leave some gear below). At 5:00 p.m. they radioed base camp and said that in the deteriorating visibility they were having difficulty making out the descent and had set up their tents to wait for a break.

Accounts of the ensuing events differ, but Vladimir Shatayev in his book notes that base camp agreed, saying to descend immediately if possible or wait the night. Craig’s book reports that Abalakov told them to descend first thing in the morning on the Lipkin, the route they had ascended and knew.

That night Steck’s group wore their boots and all clothing to bed in case their tent shredded. The Americans had nylon tents with zippers and aluminum poles. Holding up the tent poles, though one snapped, they would outlast the storm. The Soviet women had cotton tents with toggle closures and wooden poles, and according to Craig the wind wrecked two tents the first night.

The morning of August 6 brought five inches of snow at base and, higher, a foot of snow and winds of 70 to 80 mph. Climbers gathered to hear radio transmissions by translator as Shatayeva radioed reports of the sustained whiteout and worsening wind.

At what Vladimir Shatayev states as 5:00 p.m. (though Craig indicates as some hours earlier), Shatayeva reported that one woman had become ill and another seemed unwell. Abalakov told them to descend.

Abalakov spoke slowly and adamantly, according to Craig, saying to reach snow in which they could dig caves.

Craig wrote, “[I]t was implied that if the sick girl could not move and they could not achieve adequate shelter, they must leave her for the good of the group as a whole.”

As the women descended, Irina Lyubimtseva died, apparently freezing to death holding a safety rope for others.

Unable to dig caves in the hard, granular snow, the women somehow managed to put up two tents on a ridge only several hundred feet below the top. The ailing climbers deteriorated. Abalakov strongly directed continued descent by those who could move, according to Craig; Shatayeva said she understood and would try.

The times given vary, but that day or into the next, the ill women (Nina Vasilyeva and Valenina Fateyeva) died. Also that day or, by Shatayev’s account in the early hours after midnight, hurricane-force winds hit, exploding the tents and blowing away rucksacks, stoves and mittens. Five women huddled in a tent without poles, with three sleeping bags.

The next morning four Japanese climbers, bivouacked in a tent at 6,500 meters on the Lipkin side and possessing a strong radio, heard the transmissions in Russian and deduced trouble. Two of the Japanese climbers bravely set out to help but were blown off their feet and forced back. Other climbers on the mountain mobilized, but all were far lower.

The final hours

The following excerpts are from Craig. Accounts and times differ somewhat, but Craig was in base camp and overall his account is considered sound, and an honest, earnest rendition.

August 7, “about” 08:00. Abalakov pressed Shatayeva as to whether the women were trying to descend. She replied with spirit: “Three more are sick; now there are only two of us who are functioning, and we are getting weaker. We cannot, we would not leave our comrades after all they have done for us.”

10:00 Shatayeva: “It is very sad here where it was once so beautiful.”

Noon. One more had died, two were dying. “They are all gone now. That last asked, ‘When will we see the flowers again?’ [Two] others earlier asked about [their] children. Now it is no use.”

15:30 [Disoriented] “We are sorry, we have failed you. We tried so hard. Now we are so cold.”

Abalakov in despair promised a rescue was underway.

17:00 Transmission unclear, but another woman seemed to have died. Three remained. Winds up high were estimated at 80 to 100 mph, the summit temperatures as minus 30 to minus 40 F.

18:30 “Another has died. We cannot go through another night. I do not have the strength to hold down the transmitter button.”

20:30 “Now we are two. And now we will all die. We are very sorry. We tried but we could not … Please forgive us. We love you. Goodbye.”

Vladimir Shatayev’s book identifies the last speaker not as his wife but Galina Perehodyuk, and suggests it was difficult to understand whether the word was “forgive” or “request.” He writes that twice more someone pressed the radio button, attempting contact with the world.

Steck says, “The events of that day are permanently etched into my brain.” On August 8 the American trio, unprepared, saw the first body on the face below the summit; Wren recognized Shatayeva. Signs of others were visible upslope. The four Japanese arrived at the same time, and the Americans borrowed their radio to call base, with Steck saying, “Something very strange, very sad has happened here.” Finding the other bodies above, they walked crying among them, amid the shreds of tent fabric and shards of poles.

Beyond Shatayeva, two women were half-buried in the snow; three, as Wren was to write in the New York Times, “sprawled across a torn tent, futilely pitched on a scooped‐out snow platform,” and another was frozen holding a rope leading downhill. The eighth was to be found beneath the others when Elvira’s husband and a support crew went up a week later to retrieve them.

That night at camp all three Americans were certain they heard women’s voices. “Russian voices,” says Steck. “We'd open the tent and no one was there.”

The reasons for the mass tragedy are many, sifted through with the benefit of hindsight.

The objective, as a traverse, put the women as camping on the summit, exposed to the worst of the storm. They had poor equipment. They were also under pressure, on show.

“They were the test group,” says Higgins. “They felt they needed to do it to uphold the standards of the women’s team.”

Wren wrote, “Rather than retreat when the storm came in, they made a miscalculation to wait until the visibility improved. I suspect that they did not want foreigners to think Russians were quitters.”

Many observed that Shatayeva felt great responsibility for her team.

Says Blum: “The women were so very loyal to each other. They stayed together until the end.”

Higgins expresses regret, respect and conflicting feelings over the series of events.

“Would it have been braver to say, ‘Let’s save the five of us?’... I just think it was really sad. I’ve felt,” she says honestly, “that she should have taken who she could and gotten out of there.

“It is huge,” she says feelingly of such a quandary. “It is a mortal decision.”

North, the last person to see the women alive (some accounts mistakenly have Scottish and Japanese climbers on the summit with them), says, “You could call them victims of circumstance.

“I don’t think without the international meet they would have been in that situation, in that weather. Same with Eva and Heidi. Because there were so many nations taking part and the overall world situation at that time, it was unusual to be there, so there was a bit of an element of people wanting to represent their nations that does not exist in normal mountaineering situations.”

John Evans (who has just died, January 9), in a published journal, “The Pamirs: Russia,” called the many fatalities “an extraordinarily sorrowful statistic … made even more distressing in the light of the very optimistic and positive intentions of our Russian hosts.” Thirteen were lost: the three Estonians, Jon Gary Ullin, Eva Isenschmid and the eight Russian women.

Anguished and noble

Williamson, in Camp III on Razdelny during the storm, says: “They weren’t weak or stupid. I place no blame on them. Those conditions converged. It was the perfect storm. I have nothing but admiration. I’m just sad those conditions came together. The storm came in pretty fast and went fast. Two days later it was bluebird skies, and we were in shirtsleeves.”

The crucial decision was the one to stay on the summit. Still, a major turning point may have occurred days earlier, in that era when women climbers were often doubted and excluded.

On Peak Lenin, Shatayeva had at first welcomed the snow, on August 4 telling Vladimir by radio, “That’s good—it covers the tracks. So that there won’t be talk that we ascended along a trail” made by others.

Nearing the main ridge August 2, Shatayeva had radioed, “Everything so far is so good that we’re disappointed in the route.”

Yet August 3 she called a rest day. Three teams of Soviet men, one of which summitted August 4, were near, clearly coordinated to provide support if needed. Vladimir Shatayev wrote, “The possibility cannot be ruled out that it was precisely for this reason that the women were dragging out the climb, trying to break loose from the guardianship.”

Had they reached the top one day earlier, they would have been lower when the storm hit.

“They weren’t weak or stupid. I place no blame on them. Those conditions converged. It was the perfect storm. I have nothing but admiration.”

Now, 45 years on, women have long proved themselves in climbing and mountaineering, are widely visible on the crags and in the peaks, and accepted as peers.

The tale of the Russian women climbers is, as Higgins puts it, “one of the epic sad stories in modern climbing history.”

During the meet, different countries worked together in disastrous and even surreal circumstances. Other people had known the Russian women to be, as Blum put it in her book, “jubilant” on the mountain, and then witnessed an anguished and noble end.

“It is so enormously tragic, occurring at a time when more women were beginning to brave great challenges on rock and in mountains,” Higgins says. "I wanted to be one of those women, and Elvira seemed invincible.”

Alison Osius of Carbondale, Colorado, is an editor at Rock and Ice magazine. She was the first woman president of the American Alpine Club.

We have updated the top locator map to better represent the specific locations of where the events took place on the border of Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan in 1974 after receiving more detail.

We also updated the story on June 12, 2020. Five Estonians were originally thought to have died on Peak Lenin in 1974 according to a number of sources. CNN has subsequently been contacted and told that two of those five Estonians survived.