Watch: What's pulling America apart?

Christine M. says that her stepfather canceled his plane ticket to her wedding in Utah because of their political differences (she’s anti-President Donald Trump, he’s pro). Justin M. won’t wear his MAGA hat in his hometown of Boston for fear he’ll be humiliated. Richard G., an independent who lives in the Tampa area, put a “No Politics Zone” sign on his door after several Trump-supporting coworkers challenged him over the latest political headlines.

Mario Benavente, a North Carolina Republican, puts it simply: “Political debate right now is a blood sport.”

These folks are only a snapshot of the reality facing Americans today. Many parents no longer want their children marrying people from a different political party — 35% of Republicans and 45% of Democrats, to be precise. Workers, like Richard, feel politics simply has no place in the office. And Americans at large dread the idea of Thanksgiving dinners with family members who might bring up President Donald Trump. Some on the right are even concerned we are on the verge of a new Civil War.

In 2019, there’s only one thing that unites us: just how divided we think we are. In fact, according to the Public Religion Research Institute, 91% of Americans feel we are polarized — and 74% feel we are extremely polarized.

Welcome to the Fractured States of America. In this series, over the next three weeks, we’ll explore the new landscape of a polarized America and examine ways to get beyond it, with the help of frequent CNN Opinion contributors and many new voices, including those of our readers.

The harm it’s causing

Politics is now a major source of stress for Americans. According to Pew Research Center, almost 50% of Republicans and nearly 60% of Democrats say discussing partisan issues — be they abortion, immigration or gun control — can be “stressful and frustrating.” And increased levels of stress are often linked to increased risks of chest pain, headache and sleeping problems. Not surprisingly, then, many Americans have also reported losing sleep and experiencing bouts of depression because of political tensions.

But it gets worse. Political division increases the risk of violence. As people begin to identify with one party or another, they isolate themselves and can become more extreme in their views. According to data from two national surveys, 15% of self-identifying Republicans and 20% of self-identifying Democrats think the country would be better if members of the opposing party “just died.” And almost 10% of people who identify as members of both major parties think violence would be acceptable if the opposing party’s candidate won the next presidential election. While these individuals represent a minority of surveyed participants, the fact that any voters are thinking in these terms is cause for alarm.

We’ve been here before

Of course, this is not the first time this country has experienced political division. At the founding of the United States, America’s first president, George Washington, warned of the dangers of partisanship — stating in his Farewell Address, “It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and … foments occasionally riot and insurrection.”

And his fears came to a frightening reality less than 100 years later when the issue of slavery led to the outbreak of the Civil War. The US lost 750,000 lives in that war, or approximately 2% of its population. But the end of the war in 1865 did not spell a unified vision for the future.

From the Great Depression to the Vietnam War, the 20th century was marked by periods of division over economic inequality, political ideology and the use of military force. However, as documentary filmmaker Ken Burns explains to CNN, “the essential thing about history, though it catalogs so many injustices and indignities, is that it always shows us that particularly the American example moves back to the center.”

For now, though, the pendulum appears to have swung toward the extremes.

How we got here

Just pause for a moment and think about the town or city you call home. How many of your neighbors voted the same way you did in the last presidential election cycle? Probably most of them. And if they didn’t, research indicates you may be considering relocating sometime soon.

Just 40 years ago, most districts in the US were swing districts. Today, less than half of them are. And this is unlikely to change anytime soon, as more and more people move to neighborhoods where they likely won’t encounter anyone who holds an opposing political view.

So, what happened over the last four decades? Journalist Bill Bishop explains we’ve been self-sorting ourselves since the 1970s, when geographic inequality in education grew. That meant Americans with college degrees began clustering in big cities, while less-educated people remained in more rural areas. And jobs migrated accordingly, with technology and production following the new city dwellers.

This clustering was followed by the rise of partisan media, social media networks and a market that was built quite literally on catering to those divisions. In other words, entire identities — defined by diet, media patterns and size of home — have been created around party affiliation. And, as sociological research explains, place, and even consumption habits, have become a way of creating identity and broadcasting it to the world — or, at least, our closest neighbor.

The dangers of self-sorting

There is an inherent danger in this form of identity politicking — it’s isolating and pushes people into their respective political tribes. In these tribes, they are not forced to rigorously interrogate their belief systems.

Identifying with our tribes isn’t inherently bad, notes SE Cupp. “Tribalism, after all, is part of our evolutionary DNA. The need to identify with a group, to belong and commune with like-minded people is not only biological, it’s what has helped motivate our desire for and devotion to all kinds of important cultural institutions, from organized religion to sports fandom.”

What isn’t natural, she says, is the increased importance we attach to politics, or the rigid allegiance to a specific political tribe — and the misperceptions of the other side that accompany it.

So much of our division, or our perceived level of discomfort with the opposing party, is imagined. For many liberals, listening to a Ted Cruz speech is seen as nails on a chalkboard, or slightly less painful than a root canal. And for conservatives, the same might be said about Bernie Sanders. Yet Harvard researchers found that the negative anticipation both sides had about these experiences far exceeded the result. When forced to listen to Cruz and Sanders, both groups said it was much more tolerable than they expected.

But it’s hard for liberals, conservatives and even independents — who research suggests usually have partisan leanings — to realize this because they live in their echo chambers, which often reinforce their existing beliefs and make them even more polarized. All of this comes at a cost — creating a massive perception gap between what Americans suspect their political opponents think and what the reality is.

The other cost? Awkward family gatherings — be it for the holidays, weddings or funerals. People feel increasingly uncomfortable around their Fox News-loving grandfather or their New York Times-subscribing granddaughter. And research indicates the solution to this is simply to not engage in political debate. Stick to sports or the weather. But do not mention the White House or its current inhabitant.

But there is some good news

Most Americans are not hyper-partisans. They comprise the “exhausted majority,” writes scholar Daniel Yudkin. They are flexible in their politics and open to compromise — especially if that means advancing legislation on issues like gun reform.

And there may be a way to re-engage them in the political process. Deborah Fallows recommends starting on the local level. While our national government may seem paralyzed most days, towns — big and small — “are often and strongly acting in a united way, facing their problems, negotiating their solutions and taking action for the greater good of their communities,” she says.

The reason is pretty simple. At the local level, people recognize the bucks stop with them — and they cannot wait for someone else to “save” them. If a school is failing, if a bridge is breaking, they are the ones who can move quickest to address the situation.

Ken Burns has another idea — share stories. “We all have stories. And sometimes they lead us back to emotions and feelings we have in common,” he explains. That may require breaking out of our red and blue silos and actually grabbing beers (Coors is the preferred drink of both parties!) with someone of a different political persuasion.

But it also involves having a frank discussion of what our core American values are.

What are our core values

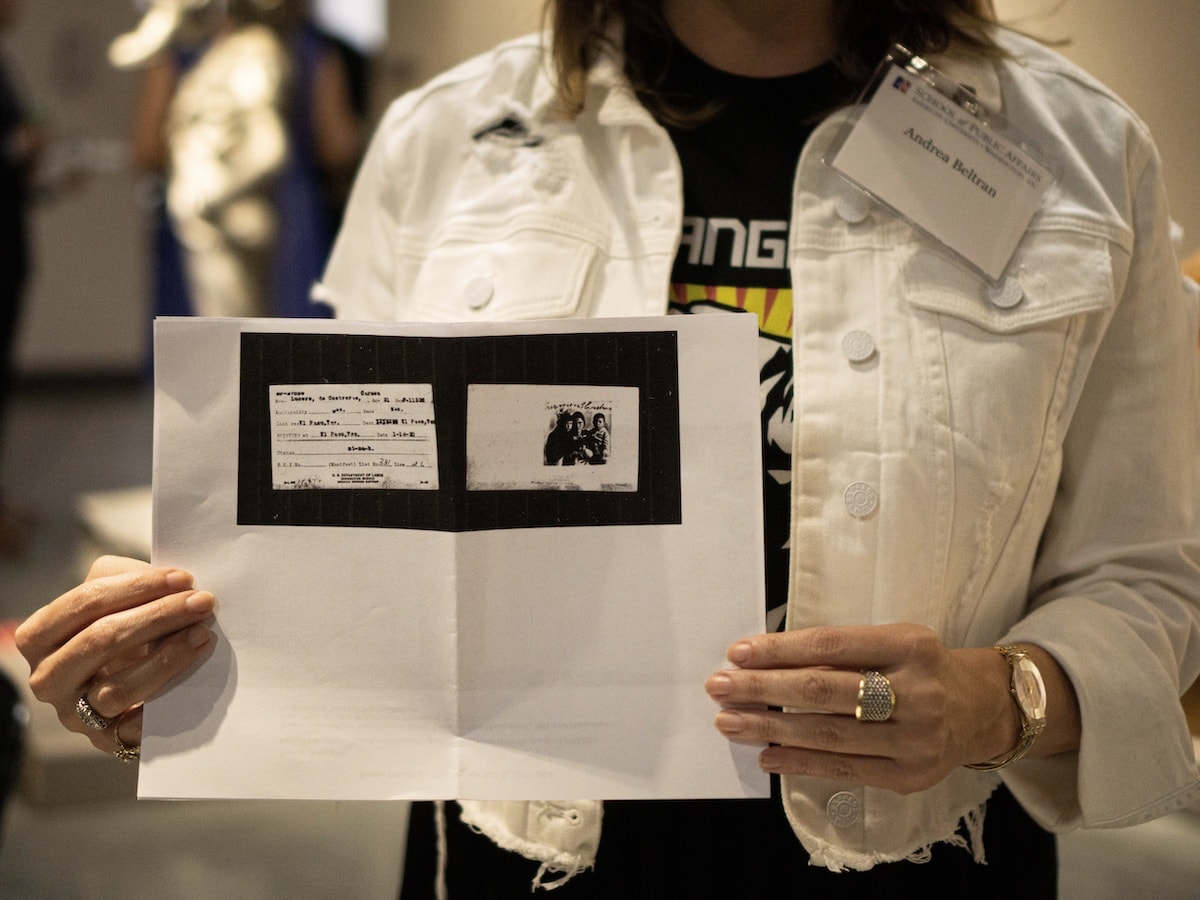

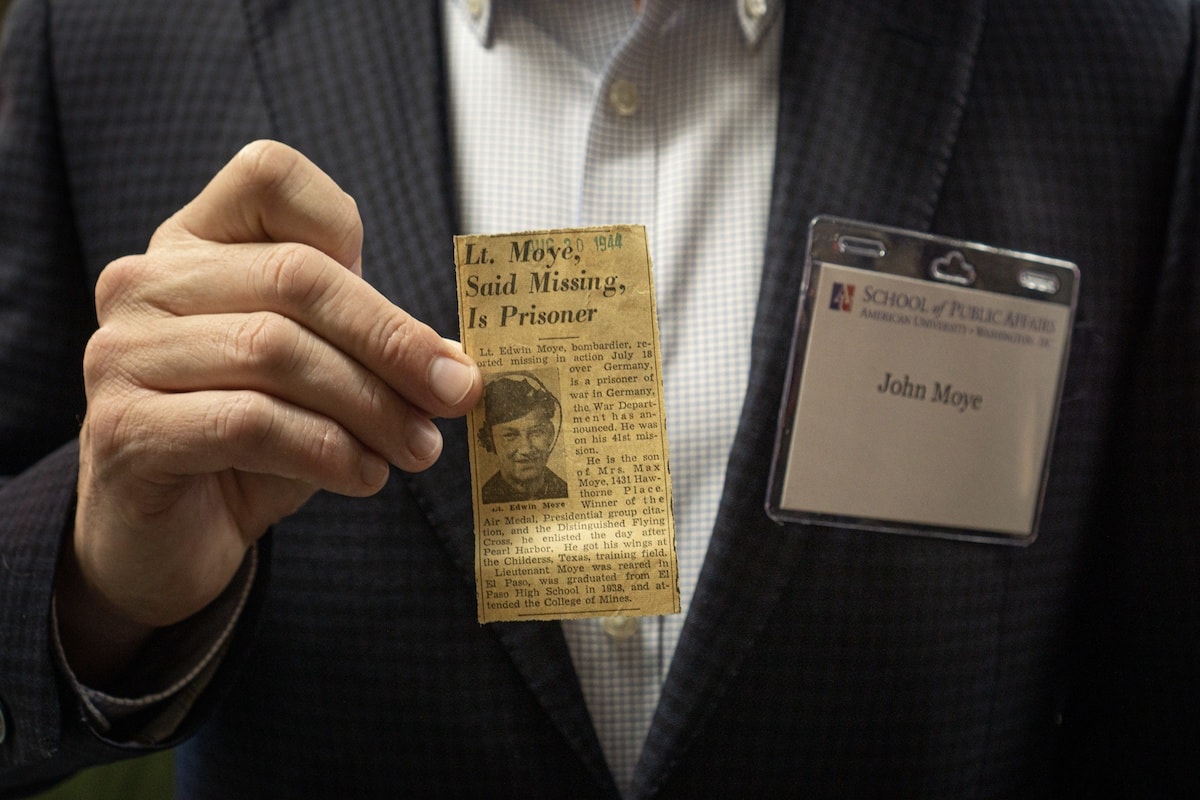

At the “Looking For America” dinner organized by New American Economy, American University School of Public Affairs and Curiosity Connects at the El Paso Museum of History, guests were asked to bring an item that illustrates their connection to their community.

Andrea Beltran, a liberal leaning writer and poet, shared her great-grandmother's 1920 nonresident alien border crossing card, containing the only photo Beltran has of the family matriarch. She explained that the card represents the idea of identity “being something hard to locate and even harder to define.” In this climate of what she calls “heavy patriotism and nationalism,” her great-grandmother reminds her just how complicated, and perhaps even dangerous, it can be to define who is and who is not American simply on the basis of birth.

John Moye, a moderate Republican and development manager for the Housing Authority, brought a 1944 El Paso Times newspaper article, which recounted his father’s experience as a prisoner of war in then-Nazi Germany. His father, who enlisted in the military the day after Pearl Harbor, survived 10 months as a POW before eventually returning to Texas. Moye emphasized that the article shows how much people at the height of World War II "truly gave of themselves and asked for little in return," a kind of patriotism he worries Americans are now losing.

Though Beltran and Moye are lifelong El Pasoans with strong connections to the city they call home, their items of choice reflect their different perspectives on this country’s fundamental values. Beltran chose the nonresident card to emphasize the complexity, but also beauty of American identity. It’s not singular — it’s messy, multilingual and built on the backs of immigrants. And trying to narrowly define it hurts us as a nation.

Moye used the newspaper clipping to showcase the importance of having a clear national identity and parlaying that into sacrifice for one’s country. His choice reflects a nostalgia for a different time, and perhaps even generation, when duty to country came first. Back then, Americans were united around a common cause — and had a strong sense of community. These days, for so many, both cause and community hang in the balance, he says.

Beltran and Moye’s differences on what American national identity should or could be is just one example of the fractured state of America. But their ability to break bread together also offers a ray of hope — one that is premised on the notion that the US is stronger because of its diversity of views, rather than its uniform acceptance of any one ideology.

As Beltran phrased it, “the best thing about this dinner was it reminded me of the human connection.” Moye seconded her, noting that though he disagreed with some of Beltran’s views, he was so grateful “that a space was finally created for these kinds of tough conversations. This country needs more of them.”