19 years old, in jail and begging to go to the hospital

Story by Blake Ellis and Melanie Hicken, CNN Investigates

Photographs by Melissa Lyttle for CNN

Teaira Shorter was only 19 years old when a family friend dropped her off at the local jail so that she could turn herself in.

She was determined to clear arrest warrants connected to her failure to pay about $1,500 in fines from minor offenses during her high school years. Unable to afford the amount needed to clear the warrants, Shorter resigned herself to serving around two weeks in jail.

The warrants, Shorter said in an interview with CNN, had been keeping her from getting a job, so she viewed the brief jail stint — at the City of Las Vegas Detention Center — as a way to move forward and start her life as an adult.

Instead, nine days after entering the jail in May of 2014, medical records and other documents show she left in an ambulance with a life-threatening infection that would haunt her with complications and medical bills for years to come.

Teaira Shorter said she was healthy and loved playing basketball before she ended up in jail. After her multiple surgeries, it took months for her to be able to play again.

Today, she still wonders why no one at the jail helped her get to the hospital sooner. And she blames the giant government contractor that had been entrusted with her medical care, a company called Correct Care Solutions, now Wellpath. A CNN investigation found that this company has been responsible for deaths and other serious medical outcomes that could have been prevented.

The company defended its overall work in interviews with CNN, saying it provided quality health care to a very needy and vulnerable population and that all medical providers experience some bad outcomes. It declined to comment on Shorter’s case, though the company has denied wrongdoing in court filings.

“I think I asked to go to the hospital, no exaggeration, 100 times,” Shorter said.

Shorter‘s time in jail was a result of several decisions she made her senior year of high school, shortly after the death of her mother. Even before that, Shorter had felt like she was on her own — bouncing around the foster system and relying on her friends and their parents to take care of her. At age 18, a fight broke out at a playground near her school, and Shorter said she showed up to see what was going on even though police were trying to clear out the area. She was arrested and charged with obstruction and unlawful assembly, according to police records.

A few months later, police records show she was riding in a friend’s car when police pulled them over and gave her a ticket for not wearing her seatbelt. When she didn’t pay the fines from either of these offenses, she said she later learned that warrants for her arrest were issued.

Before turning herself in at the City of Las Vegas Detention Center, Shorter remembers eating her aunt's home cooking, then asking to stop at McDonald's along the way for a Quarter Pounder with cheese.

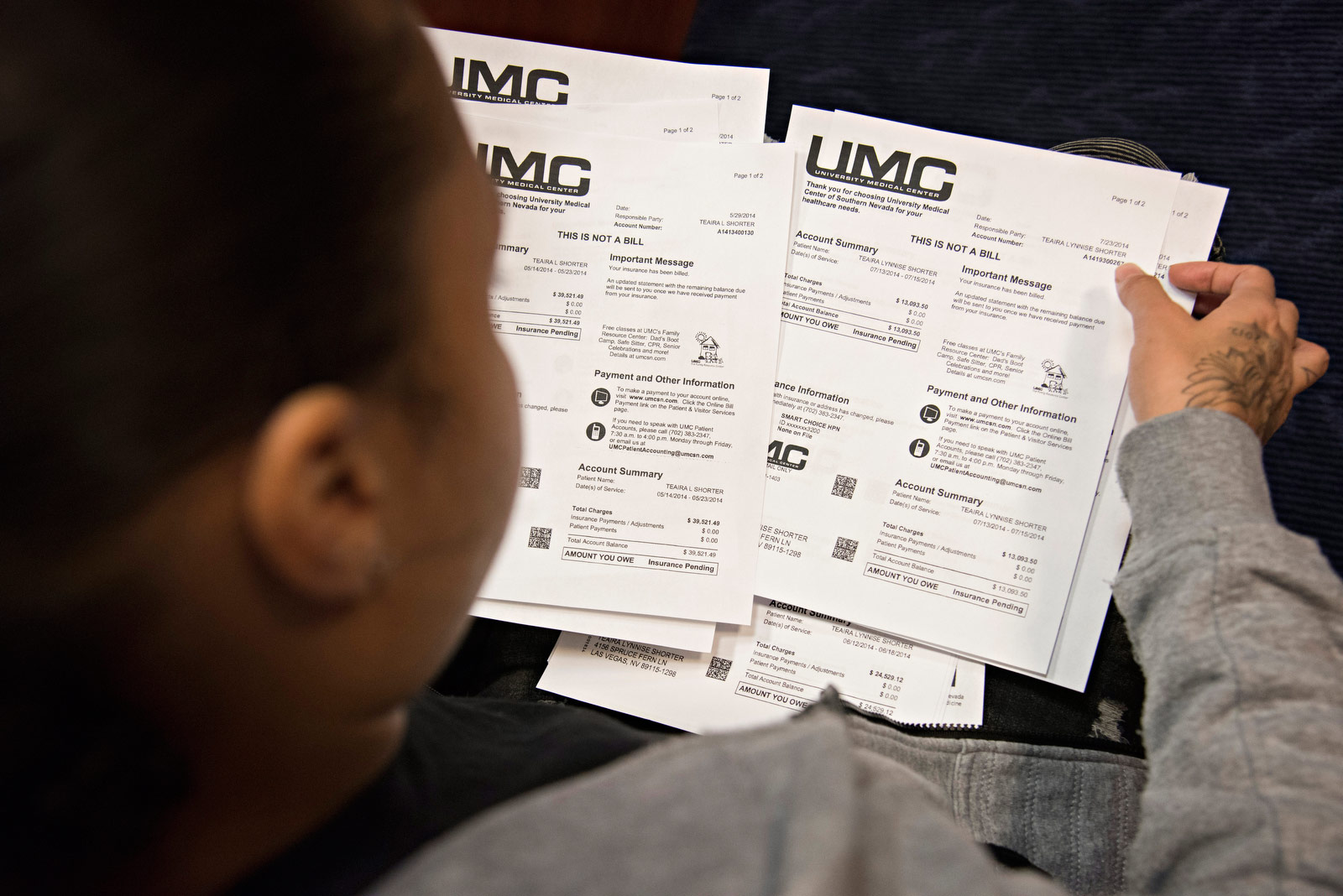

Shorter adds up the tens of thousands of dollars in medical bills from her hospital stay and surgeries.

On Shorter’s right arm is a Tupac Shakur poem about a rose that grew from concrete. On her hand is a dove with her mom's birth and death dates.

She arrived at the jail on a Monday in May, and remembers the officers being surprised that she was choosing to turn herself in. The intake area smelled like urine, she said. She could hear people yelling and banging on doors.

Shorter said she was then brought to a cell, where she spent her time reading a book. It wasn’t too long before she started to feel nauseous and then began vomiting uncontrollably. Unable to hold down any food or water, medical records show the vomiting went on for days and that she complained of stomach pain, but she was treated with anti-nausea medications and electrolyte drinks.

Shorter sits on a playground across from her old high school, near where fights used to occur after school.

She said she begged for additional medical attention over and over again. At one point she told jail officials: “I can’t breathe. I need to go to the hospital,” according to an incident report. Shorter is adamant her pleas were ignored and the severity of her symptoms were dismissed by the medical staff. In the end, records show it took around a week for her to be sent to the emergency room, where doctors discovered her appendix had ruptured and filled her abdomen with a dangerous infection.

Shorter sued both the jail and CCS, its medical provider, arguing that she should have been sent to the hospital days before her appendix burst.

“Maybe you could listen to people,” she said in the interview with CNN. “Someone's telling you something is wrong, maybe there's something wrong.”

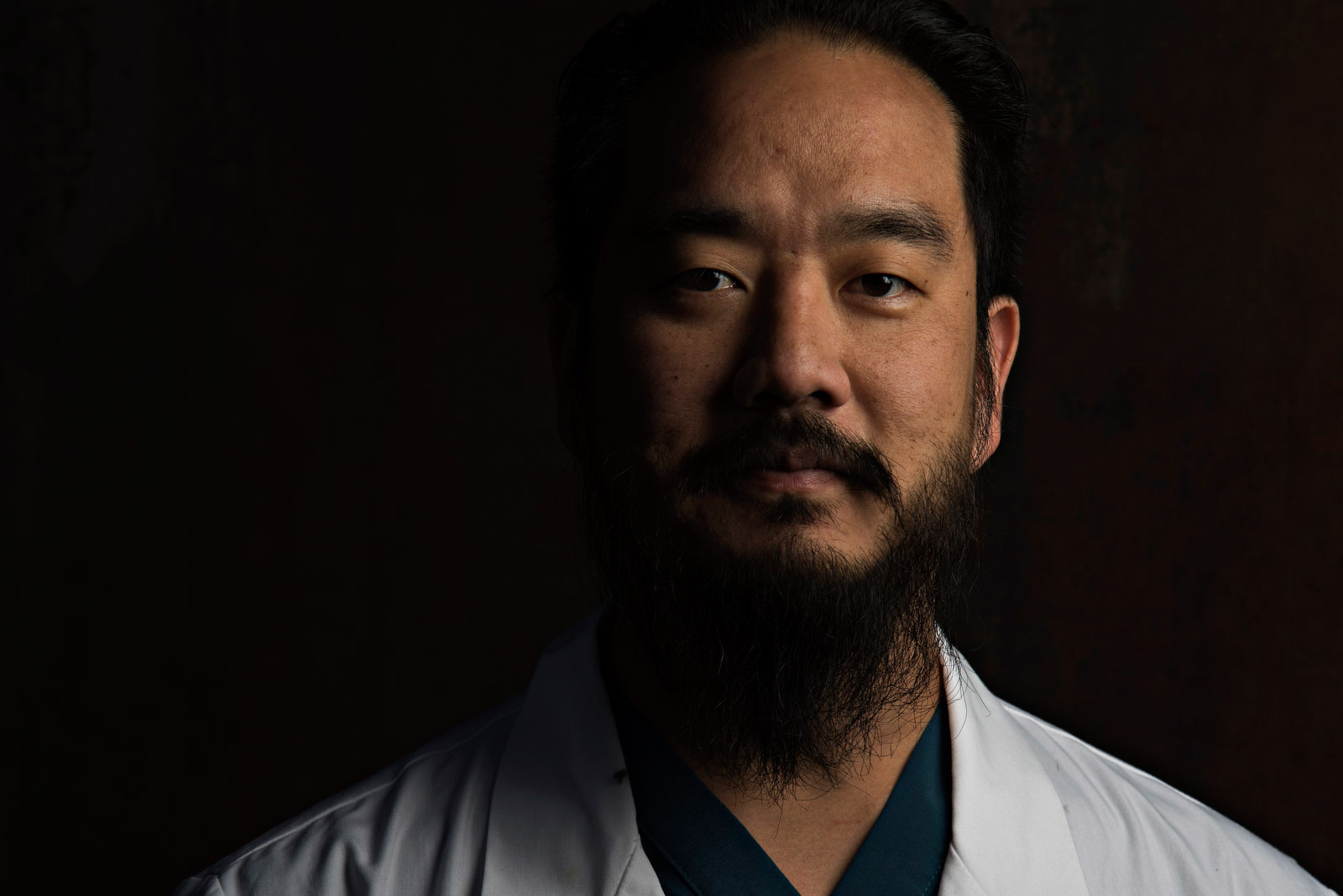

Dr. Shawn Tsuda examined Shorter when she finally ended up in the Emergency Room.

City officials declined to comment on Shorter’s case. An expert witness for the defendants disputed Shorter’s hospital diagnosis in court filings, saying that he didn’t believe there was evidence to firmly establish that her appendix had ruptured. He said her symptoms could have come from a ruptured ovarian cyst and that CCS provided appropriate care.

But Shorter’s surgeon, Shawn Tsuda, said she arrived at the hospital describing the classic signs of appendicitis and that he is confident her appendix burst and stands by his diagnosis.

He said that because medical staff at the jail hadn’t caught this, she developed an infection that could have killed her, and she needed multiple surgeries.

“I was a kid,” Shorter said. “I felt like they’re supposed to take care of me.”

Shorter said she believes this all happened because no one took her seriously, and she feels that employees treated her like a criminal.

“I’m not a criminal. I don’t do drugs,” she said. “No one came, and knocked on the door, and got me. I didn’t get pulled over and taken to jail. I brought myself here. … I was trying to be a responsible young adult and they just smacked me in the face.”

Photo editor: Brett Roegiers