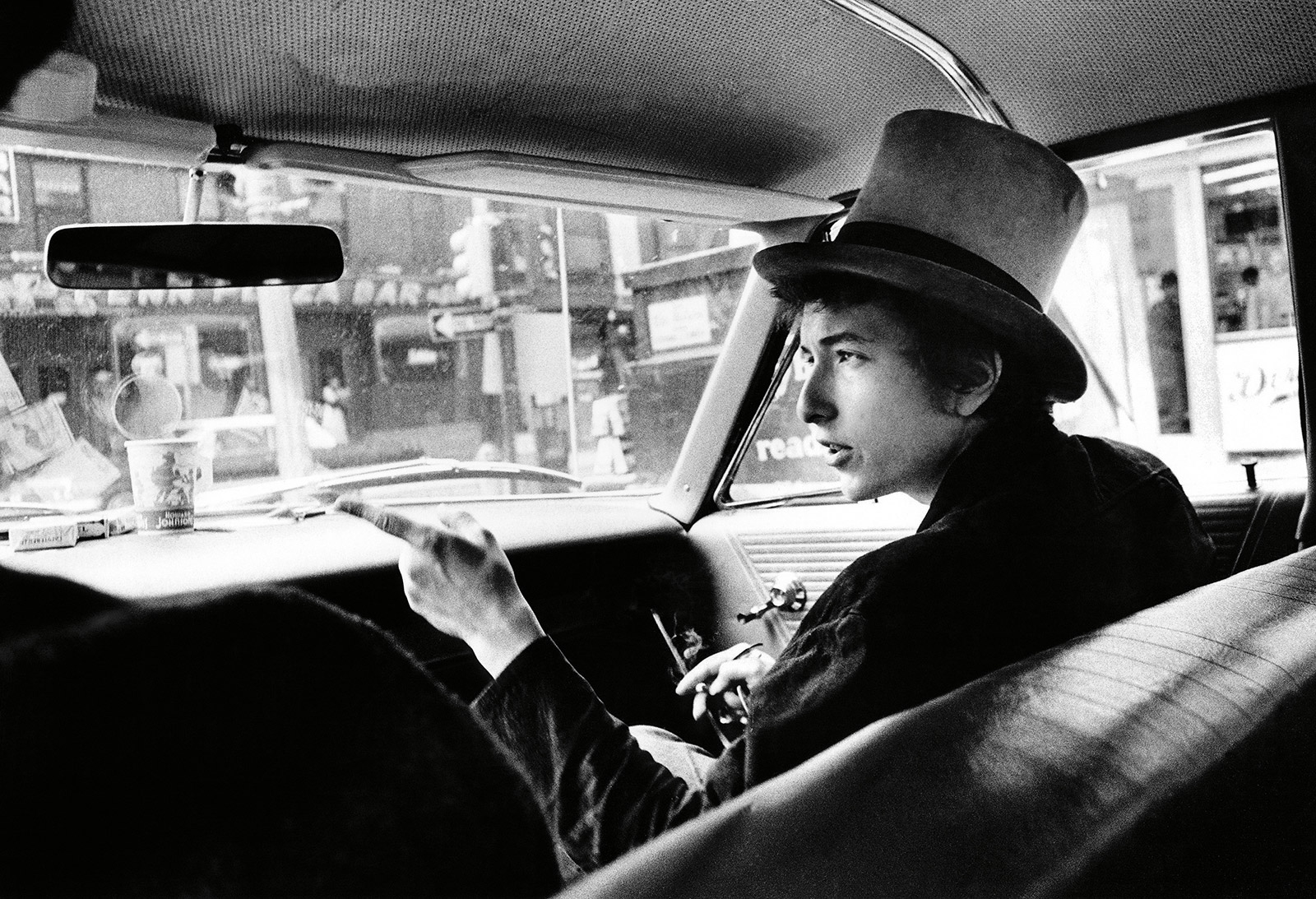

A 23-year-old Bob Dylan rides in a station wagon on the way to a concert in Philadelphia in 1964. (Daniel Kramer)

A year — and a day — with Bob Dylan

Photographs by Daniel Kramer

Story by Kyle Almond, CNN

A 23-year-old Bob Dylan rides in a station wagon on the way to a concert in Philadelphia in 1964. (Daniel Kramer)

It was only meant to be an hour.

One hour for Daniel Kramer to photograph Bob Dylan at a home in Woodstock, New York, in August 1964.

But then one hour dragged into several. Then it became lunch. And eventually, Dylan invited Kramer to go on the road with him.

Literally. In the same station wagon.

A close-up of Dylan from the first day he met photographer Daniel Kramer in 1964. (Daniel Kramer)

A portrait of Dylan, taken in Kramer’s New York studio in 1965. (Daniel Kramer)

The results of this extraordinary access can be found in “Bob Dylan: A Year and a Day.” The book contains nearly 200 images of Dylan on stage and behind the scenes, and it documents one of the most important time periods of the singer’s career.

Over the next year, Dylan would release classics such as “Like a Rolling Stone,” “Mr. Tambourine Man” and “Maggie’s Farm,” and he would start performing with an electric guitar — a controversial move for a star who at the time was known only for his acoustic folk music.

This is the year, Kramer said, that Dylan turned into a butterfly, and the book “takes Bob from the one kind of performer he was to the kind of performer he was growing into.”

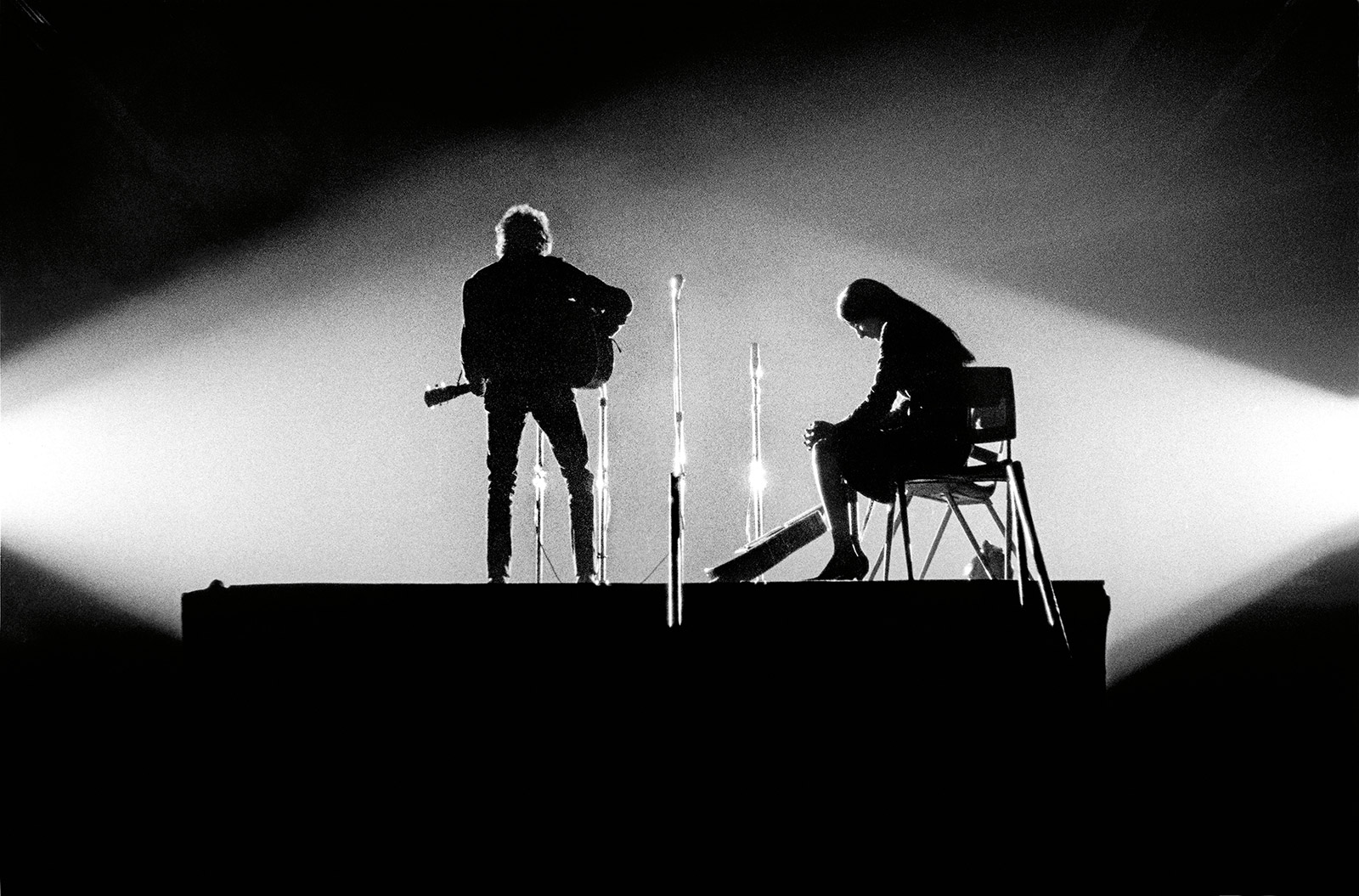

Dylan performs with Joan Baez at New York’s Lincoln Center in 1964. (Daniel Kramer)

Kramer remembers first seeing Dylan perform while watching “The Steve Allen Show” in February 1964.

He was struck by the 22-year-old singer as he listened to the lyrics of “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll,” which was about a real-life black woman in Baltimore who had recently been killed by a white man.

“People didn't sing about those things easily on TV. People just didn't do it,” Kramer said. “It was too scary and too dangerous. It was an era in which a President was shot. A great religious leader was shot. Other important movers and shakers in our society were shot. We were a shooting gallery here in the '60s, and here was this guy who looked like he was in his early 20s, singing about something very critical and very touchy. Well, that got my attention.”

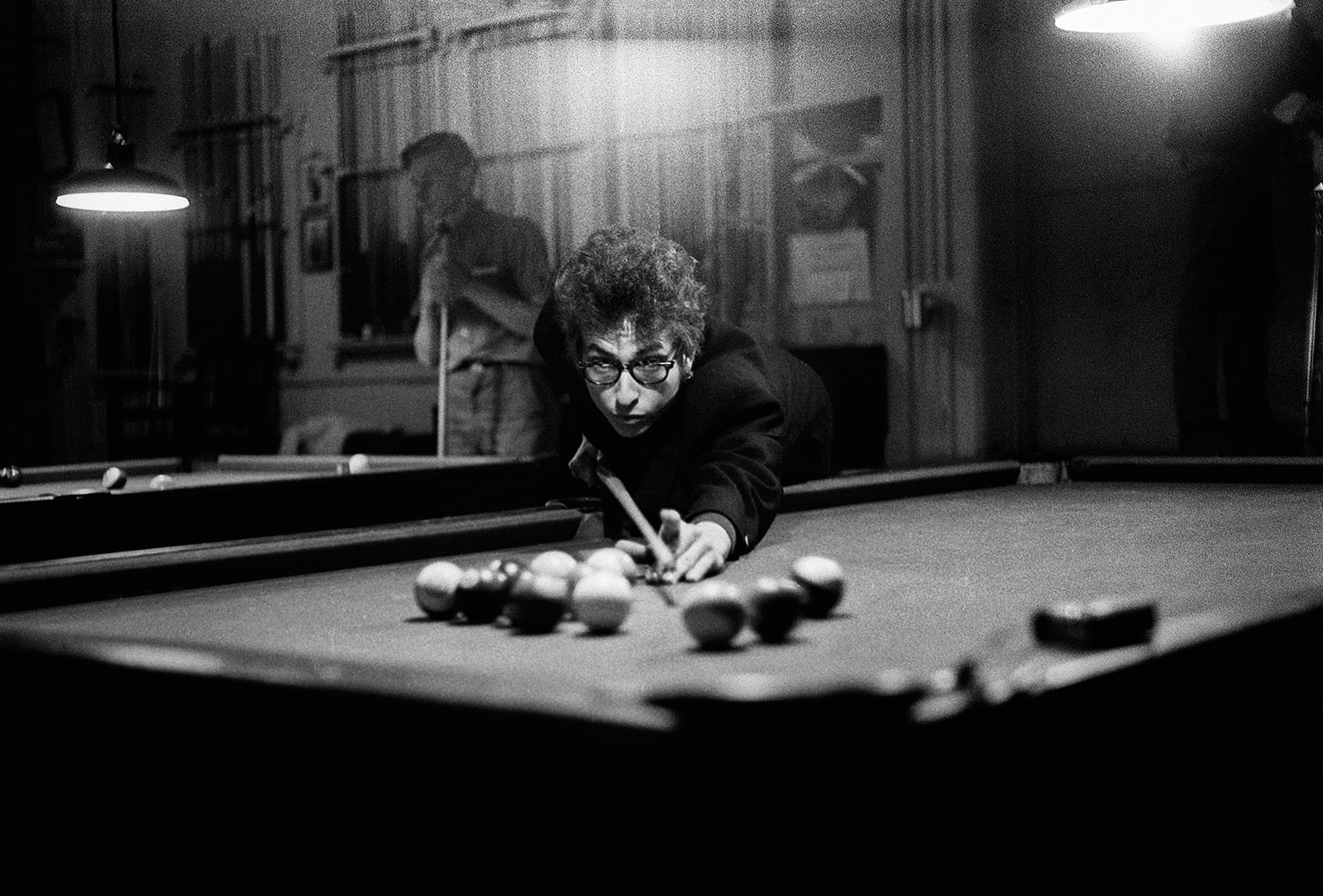

Dylan shoots pool in Kingston, New York. (Daniel Kramer)

Kramer had just recently opened his first studio in New York, and he was hoping he could add Dylan to his portfolio. So he reached out to Dylan’s management agency, making calls and writing letters.

For six months, he got nowhere. But he kept trying, and a breakthrough happened one day after business hours, when a call was picked up by Dylan’s manager instead of a secretary.

Albert Grossman invited Kramer out to his home and promised him an hour.

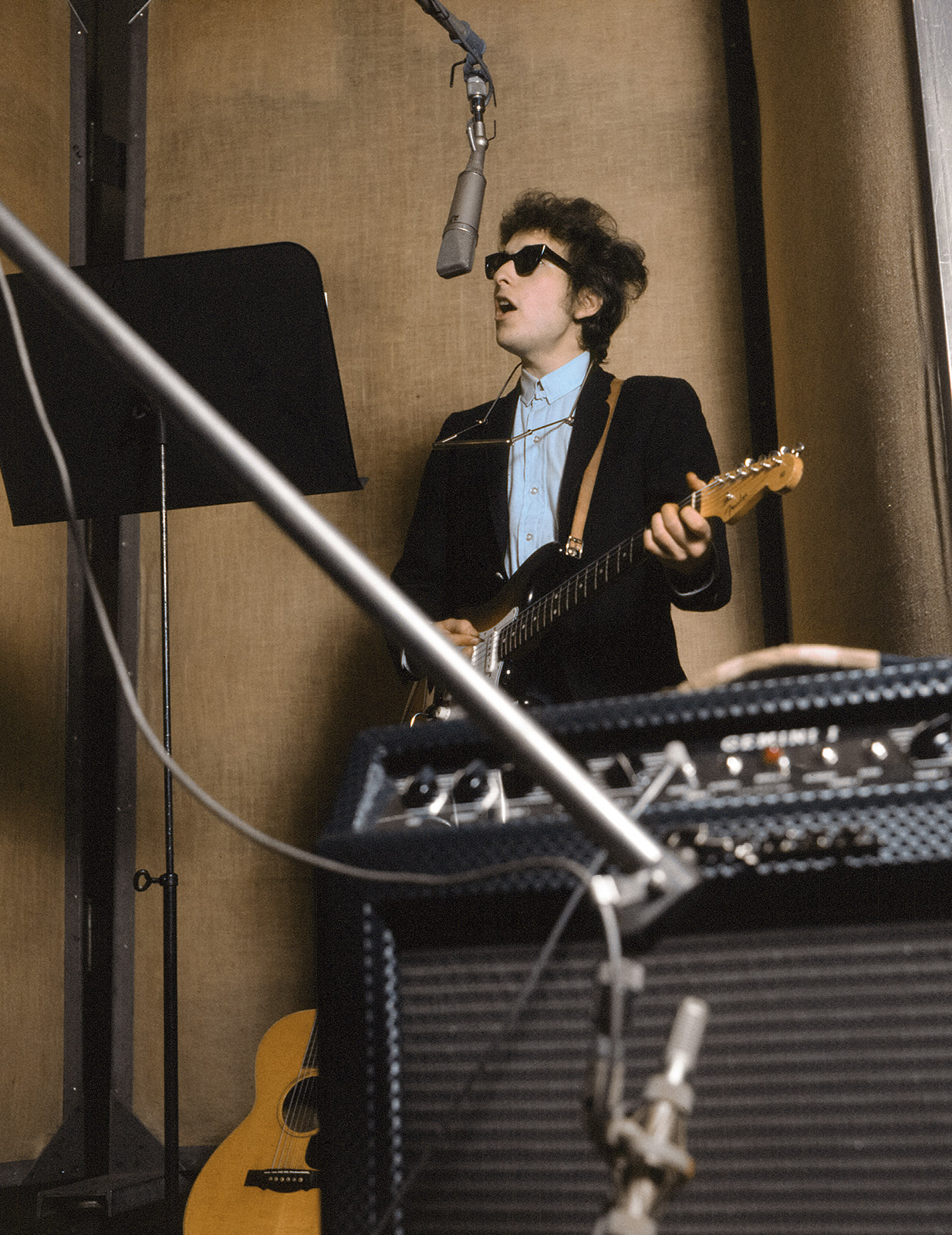

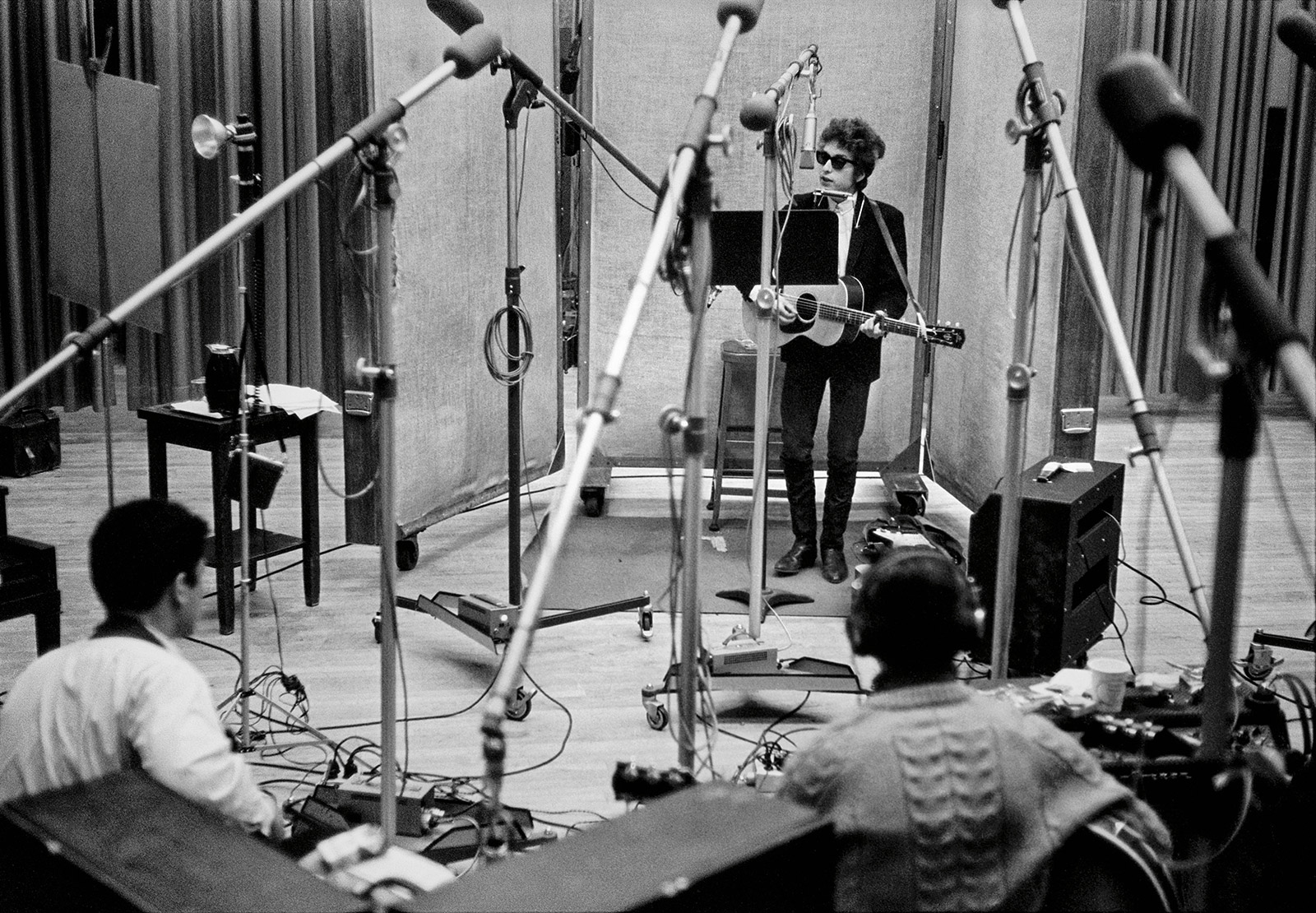

Dylan records a song in New York in 1965. (Daniel Kramer)

Dylan, right, sits in the back of a truck in New York with friends John Hammond Jr., left, and Peter Yarrow. (Daniel Kramer)

When Kramer got to the home, Dylan wasn’t even there. He showed up about an hour and a half later on his motorcycle and greeted Kramer with a gentle, “almost nonexistent” handshake.

“Some people don't give you anything at first,” Kramer recalled. “They don't know who you are.”

But the two soon got into a rhythm, with Dylan going about his day, reading the paper, climbing trees, watching movies. He didn’t like the idea of just sitting for a portrait.

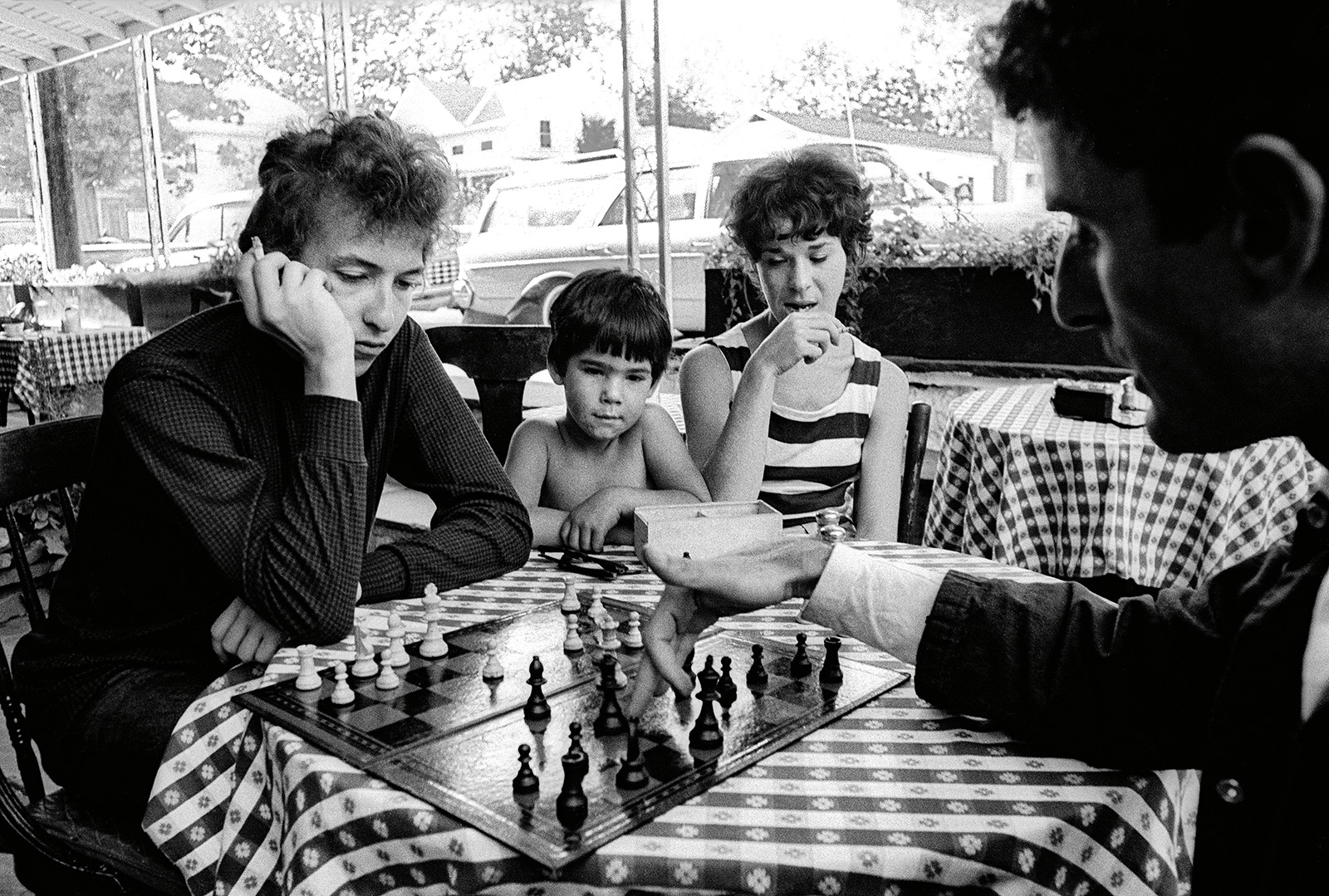

Dylan plays chess with his road manager, Victor Maymudes, at a restaurant in Woodstock, New York, in 1964. (Daniel Kramer)

“He said, ‘You can do anything you want, you can shoot anything you want the whole day, whatever you want — as long as I don't have to sit still in the chair,’ ” Kramer said. “He's always in motion, even when he's sitting.”

Later in the day, they had lunch at a local restaurant, where Dylan played chess with his road manager. And when it was time for Kramer to eventually leave, he got a much warmer handshake from Dylan.

“Like I suspected, he just was cautious,” Kramer said. “And I guess you have to be in this business.”

Dylan recording in the studio. (Daniel Kramer)

Kramer next met Dylan and Grossman at an office where he showed off his photos from the shoot. Dylan must have liked what he saw.

“He said, ‘I'm going to Philadelphia next week, you want to come?’ And that's how it started,” Kramer said.

Dylan and his road manager picked up Kramer in a station wagon, and the two really started to get to know each other during the road trip.

Dylan performs on “The Les Crane Show” in 1965. (Daniel Kramer)

Shooting photos at Philadelphia’s Town Hall, Kramer watched fans go crazy as Dylan strolled up to the mic, tuning his guitar. Then they went quiet as he started to perform.

“Bob always got a certain respect — from the audience, from journalists, from most of the people around him and in the business,” Kramer said. “He was that person who you give respect to because he was special.”

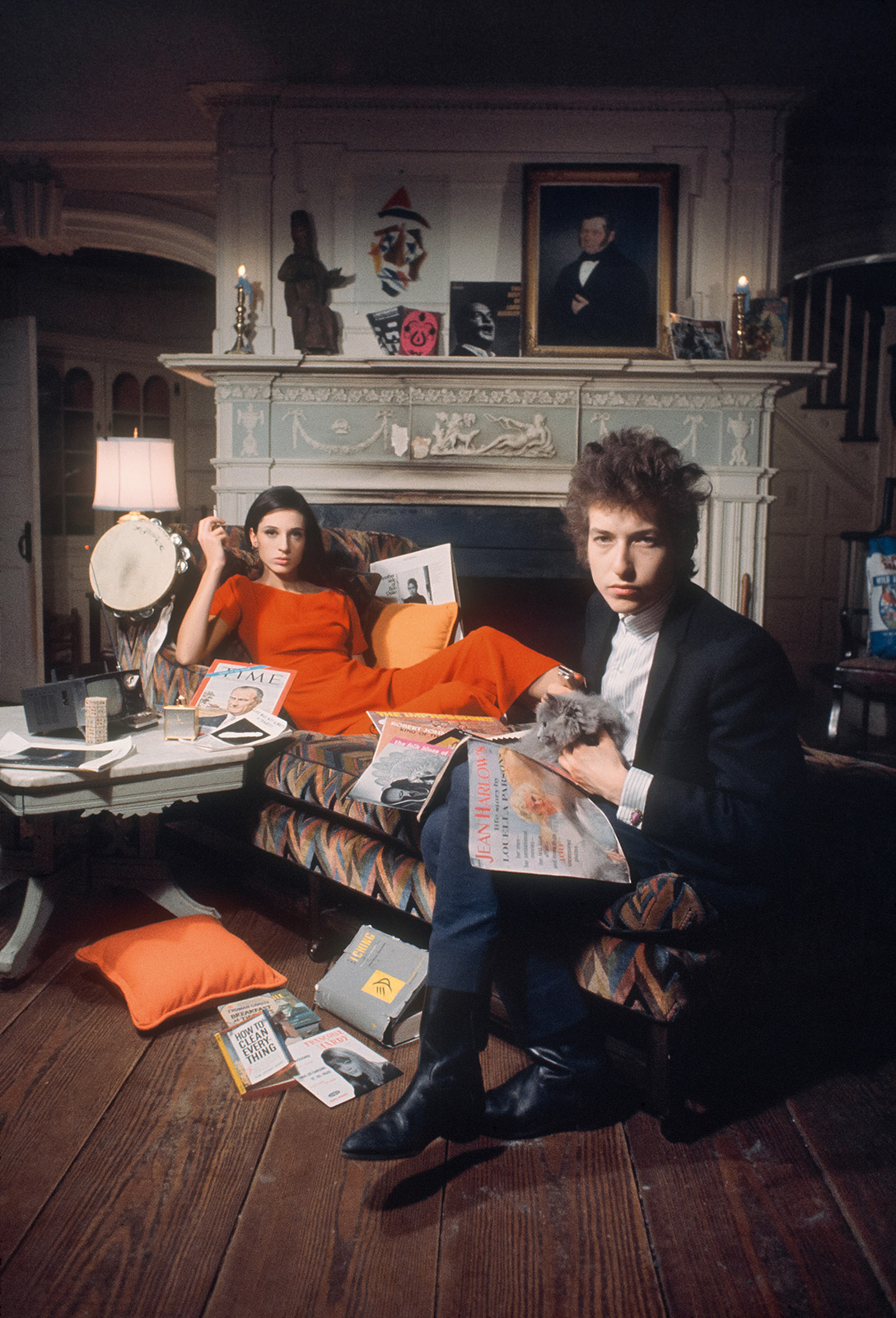

A photo from the cover shoot for the album “Bringing It All Back Home.” The woman on the cover is Sally Grossman, the wife of Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman. (Daniel Kramer)

Dylan and his famous harmonica. (Daniel Kramer)

Dylan continued to invite Kramer to shows for much of the year, and Kramer even produced a couple of Dylan’s album covers, including the Grammy-nominated cover for “Bringing It All Back Home.” That was the album that was acoustic on one side, and electric on the other.

“It was a very important cover for Bob,” Kramer said. “And the reason is the first four albums he did, he's a folk singer. He's in folk singer clothes, he looks, you know, ‘Oh, woe is me.’

“On ‘Bringing It All Back Home,’ he's a prince in his blazer and his beautiful cufflinks sitting with this beautiful cat and a ravishingly beautiful woman behind him in a red dress. It was a change. Everything was changing.”

Dylan and Joan Baez perform in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1965. (Daniel Kramer)

Kramer’s final shoot with Dylan came at the infamous Forest Hills concert in New York, where some fans booed Dylan for switching from acoustic to electric after the intermission.

That show took place on August 28, 1965 — exactly one year and a day after Kramer had first photographed him in Woodstock.

Daniel Kramer is a photographer based in New York. His book “Bob Dylan: A Year and a Day” is available through Taschen.

Photo editors: Clint Alwahab and Brett Roegiers