Photo illustration/AP Images

In the mid-1990s, Ye Jianming had a simple job in a forest, or so his story goes. Twenty years later, he sat atop a $44 billion business empire. Today, he has vanished and, as that empire crumbles, is reportedly under investigation by the Chinese government.

How all that happened remains largely unknown. But one thing is clear: at its height, Ye’s company, CEFC China Energy, aligned itself so closely with the Chinese government that it was often hard to distinguish between the two.

The young tycoon appeared to be China's unofficial energy envoy, meeting presidents across the globe and even becoming an adviser to a European government. In 2016, he ranked No. 2 on the Fortune magazine 40 Under 40 list.

But last November, Ye’s seemingly unstoppable rise came to a screeching halt. His undoing came after US prosecutors alleged that an NGO he funded had used its United Nations status to offer millions in bribes to African leaders, although he is not charged.

As that case plays out in a Manhattan courthouse, the world is offered a rare glimpse into the complex relations between private business and the Chinese state -- and with it, a cautionary tale of what happens when a Chinese company fails abroad.

Czech invasion

Ye came to international prominence in the summer of 2015, following an extraordinary buying spree in the Czech Republic.

As the chairman of CEFC China Energy, Ye snapped up the country's oldest football club, Slavia Praha; a brewery; a share of the Travel Service airline group; a publishing house; a neo-renaissance building; a stake in the investment bank J&T Finance Group; and a building in the Czech capital Prague, intended for use as the company's European headquarters.

A CEFC China Energy sign in Shanghai, China. Newscom

Inside the Czech Republic, the acquisitions were greeted with bemusement: Why would an energy company want a brewery? And why was a Chinese company suddenly so welcome in a country that had, until recently, been hostile to China?

As with just about everything involving CEFC China Energy, the answers would eventually point to the Chinese government.

From its founding in 1993 until 2003, the Czech Republic was led by Vaclav Havel, a dissident turned elected politician, whose impassioned campaigning had helped topple the country's former communist government and usher in a new era of democracy. Throughout his decade in office, Havel made no attempt to hide his disdain for China's own communist rulers, regularly meeting with the Dalai Lama -- who is considered by China to be a dangerous separatist.

Relations changed with the election of Milos Zeman to the top office in 2013. Touted as the Czech Republic's first China-friendly president, Zeman was keen to facilitate increased trade between Beijing and Prague. The following year, a Czech entity would become the first wholly foreign-owned company to provide loans across China, a huge coup in the country's relatively untapped consumer credit market.

Ye sensed an opportunity.

He was quietly made a special economic adviser to Zeman, something that would only be announced six months after the fact. Miroslav Kalousek, a Czech opposition MP, says he considers Ye’s role in his country’s government as "scandalous and a security risk."

Shortly after Ye's appointment came his high-profile splurge. The deals made no commercial sense, says Martin Hala, a leading Czech academic in Chinese studies. But they sent a clear message from Beijing to the international community that China now had a firm friend in Europe.

That was important. Chinese President Xi Jinping's flagship Belt and Road initiative aims to export Chinese commerce, goods and influence across the globe. A foothold in the Czech Republic gave China a gateway to Europe, and a valuable political ally within the European Union, Beijing's largest trading partner.

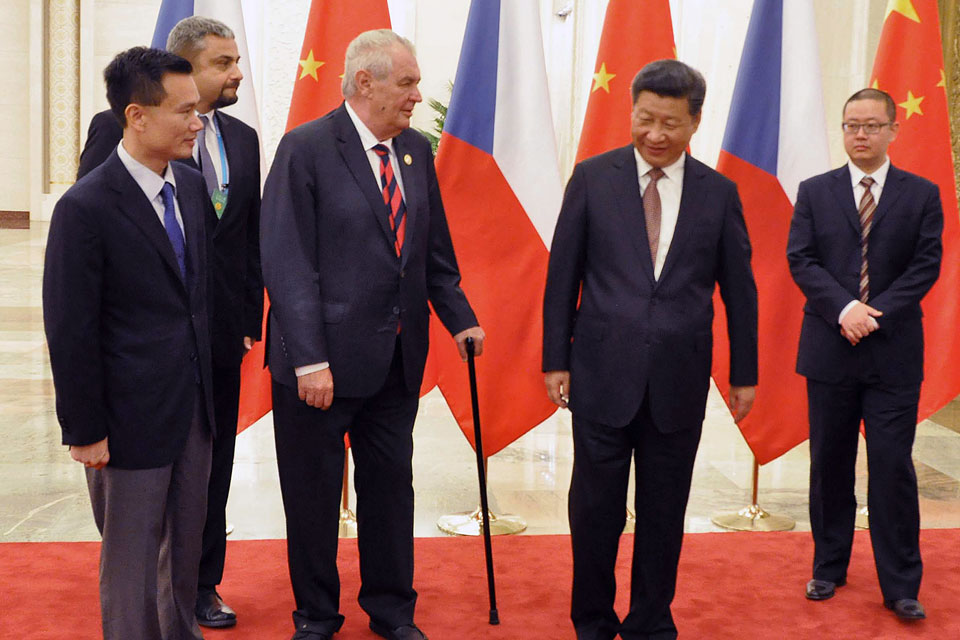

Chinese President Xi Jinping, second from right, with Czech President Milos Zeman, third from left, at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing in September, 2015. Ye Jianming is on the far left. Lucie Mikolaskova (CTK via AP Images)

Stephen Platt, an American historian and professor of Chinese history at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, says there is a long history of private businessmen advancing the influence of their country abroad, dating back to the British East India Company and the cotton and silk traders who sparked the Opium Wars in China. "It takes the risk and financial burden off the Chinese government," he says. "If the companies go bankrupt that's their problem and (in the meantime) the government can take advantage of (them) spreading a positive view of China and increasing China's influence."

When Zeman met with Xi Jinping in Beijing in 2015, Ye was photographed with both presidents. His proximity to the center of Chinese power had never looked stronger.

No prince

The Czech deals caused a buzz around Ye.

"Journalists would be calling me up asking: 'What do you know about this?'" says Laban Yu, the head of China research at the Jefferies Group investment bank. He would shrug. CEFC China Energy “came out from nowhere,” says Yu.

By 2018, it was widely reported that CEFC China Energy had a global property portfolio worth $3.2 billion, including office space in central Hong Kong and a Trump World Tower apartment in Manhattan. The company employed nearly 50,000 people, was ranked No. 222 on the 2017 Fortune 500 list and in 2015 made about $40 billion in revenue.

“(CEFC China Energy) came out from nowhere”Laban Yu, head of China research at the Jefferies Group

In 2016, Ye granted Fortune magazine what remains his only interview with Western media. It was an opportunity to address questions of his alleged government ties.

For years, rumors had circulated in China that Ye was a People’s Liberation Army (PLA) princeling -- the name given to offspring of the founding fathers of the People's Republic of China, who used their power to amass vast wealth. Many princelings hold top positions in state-owned enterprises (SOEs) or are high-ranking politicians. President Xi, for instance, is the son a former vice premier of the State Council. In China, princeling status is often considered the fastest way to get rich.

Onlookers theorized that Ye Jianming's grandfather was a high-ranking Communist Party official called Ye Jianying. A biography of the younger Ye in a 2012 financial report seemed to support claims of high-level PLA ties. It states that from 2003 until 2005 he was the deputy secretary general of the China Association for International Friendly Contact (CAIFC). That group is a purported political arm of the Chinese military, according to a report by the Project 2049 Institute, a US-based organization that researches Asia security issues. Stylistic similarities between the CEFC China Energy and CAIFC logos did nothing to dispel the idea that Ye was linked to the military.

In an email, CAIFC denied that Ye Jianming had been deputy chair of the organization and that it had military ties.

CEFC, CAIFC

Ye wanted people to believe CEFC China Energy was intimately related to the highest levels of the Chinese state, says Andrew Chubb, a postdoctoral fellow in the Columbia-Harvard China and the World Program.

But when asked about the issue, Ye told Fortune he didn’t have military ties.

From the yellow stars in its logo to the fact it had China in its name -- a privilege normally reserved for state-owned companies -- CEFC China Energy’s messaging strongly suggested state ties. So why was Ye denying links?

“To me, it's a story of how people who are really unimportant can make things happen”Bonnie Glaser, senior adviser for the Center for Strategic and International Studies

Perhaps some of his ties were not that strong.

Bonnie Glaser, director of the China Power Project in Washington, says she was introduced to Ye in 2010, in Shanghai, through a PLA admiral who was writing the proposal for CEFC China Energy to set up an NGO at the United Nations. The admiral wasn't overly influential or wealthy, she says, but spoke good English and knew Western procedures. The following year, Ye's NGO was officially recognized by the UN.

"To me, it's a story of how people who are really unimportant can make things happen," says Glaser, who has advised the US government on Chinese affairs.

In his Fortune interview, Ye provided an alternative story to the PLA princeling rumors: After a stint in the forest police, while still in his early 20s, he somehow managed to buy oil assets at auction from a businessman who had fled Ye’s home province of Fujian in southern China. Ye insisted it was Hong Kong and Fujian businessmen who gave him the cash. “But why they would put a 20-something in charge of that is totally mysterious,” says Chubb. Chinese journalists who subsequently traveled to Ye's parents’ home claimed his family were modest fishermen.

The Belt and Road

On a quiet, tree-lined street in Shanghai's former French Concession district, amid the city's most historic and expensive real estate, lies the CEFC China Energy compound. Designed as a Western-style palace, the compound features 20 villas replete with white marble pillars, as well as a Chinese pavilion. Once the headquarters of the firm, today all CEFC China Energy signs have been stripped from the gate.

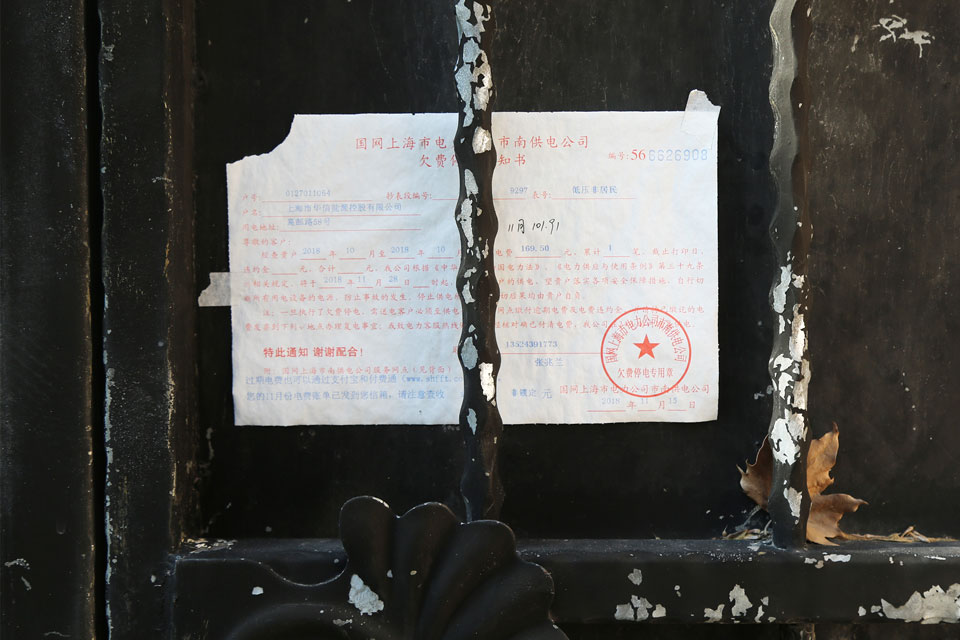

A CEFC charity is located 100 meters away from the CEFC HQ compound. This notice says the power supply is to be cut owing from November 28 due to overdue bills. CNN

A sketch of the building from CEFC’s website. CEFC

The side gate of the CEFC compound in November 2018. CNN

Ye relocated to Shanghai from Fujian around 2009, according to records seen by Chinese financial news outlet Caixin. "He was part of a Fujian clique that all rose together," says Chubb, whose blog, South Sea Conversations, has closely tracked the CEFC China Energy story. The group emerged while Xi Jinping was still in the Fujian government. It moved to Shanghai around the same time as Xi did -- although it is unclear whether or not their lives intersected.

It was in Shanghai that Ye's business empire mushroomed. He became the epicenter of a multi-billion-dollar constellation of companies based in the Czech Republic, Singapore, Hong Kong, Bermuda and mainland China. In 2011, his company's NGO, the China Energy Fund Committee, was awarded consultative status at the UN. It was a highly unusual, if not unprecedented, move for a private energy company.

Why a Chinese energy company would fund an NGO at the UN puzzled Glaser, the US academic who had met Ye. Officially, its mission was to serve as "a high-end strategic think tank" on energy. Much of the NGO’s time was spent holding conferences on the Belt and Road initiative. The events were surreal for being so "pro-China," says Glaser.

Still, they attracted an impressive crowd. A former head of an oil conglomerate, US and Russian ex-diplomats, and retirees of America's National Security Agency and the CIA all appeared at the NGO’s events.

“I didn't have a clear idea, and for that matter still don't, what the China Energy Fund Committee was”Hugh White, professor of strategic studies at the Australian National University, in Canberra

"I remember ... thinking, wow, they're bringing in really senior people now," says Glaser.

But many scholars who attended the NGO’s forums had never heard of Ye. They assumed the China Energy Fund Committee was a vessel of the Chinese government, says Hugh White, of the Australian National University, who took part in one such event in 2015. He pauses before adding: "But I didn't have a clear idea, and for that matter still don't, what the China Energy Fund Committee was"

At the UN, employees of Ye’s NGO were rubbing shoulders with some of the most important men in the world. In the four years after the NGO arrived in New York, CEFC China Energy's revenue grew by 25% annually, according to the company's website.

As CEFC China Energy thrived, Ye traveled the world on his private Airbus glad-handing leaders, including President Erdogan of Turkey, the former US secretary of state Henry Kissinger, the prime minister of Kazakhstan, and Alan Greenspan, the former US Federal Reserve chairman.

With better political connections came bigger international deals. In 2016, for example, CEFC China Energy established trade deals in Georgia and reached a $680 million agreement -- which has since fallen through -- with a Kazakh state oil and gas firm. The next year, it spent $900 million on a stake in a huge oil field majority-owned by Abu Dhabi National Oil Co.

In its press releases, CEFC China Energy billed many of these ventures as Belt and Road deals, further aligning itself with the Chinese government.

"There is no type of project that doesn't qualify as Belt and Road, and no continent on the planet that doesn't have Belt and Road," says Christopher Balding, an associate professor at the Fulbright University Vietnam. Due to tight capital controls, Chinese companies struggle to move money abroad, he explains. Calling deals “Belt and Road” projects helps companies gain the support of the Chinese government to do business internationally and move money out of China, adds Balding.

“There is no type of project that doesn't qualify as Belt and Road, and no continent on the planet that doesn't have Belt and Road”Christopher Balding, an associate professor at the Fulbright University Vietnam

In September 2017, CEFC China Energy announced its most high-profile investment yet. The company was to buy a 14% stake in Russian oil giant Rosneft for $9 billion -- the sort of super spend usually reserved for a state-owned company.

That raised eyebrows, says Laban Yu, at the Jefferies Group investment bank. "I thought, who would give them that kind of money?"

The empire falls

Film star Jackie Chan (left) and the then Hong Kong Home Affairs secretary Patrick Ho at an event raising money for the Jackie Chan Charitable foundation, the United Nations Children's Fund and the Community Chest. Samantha Sin/AFP/Getty Images

Ye’s empire began to crumble on November 18, 2017. On that day, FBI agents arrested Patrick Ho Chi-ping, the man Ye had employed to lead his NGO. Ho was charged with money laundering and violating the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. He is accused of offering $3 million in bribes to the President of Chad, Idriss Deby, and Sam Kutesa, the Ugandan minister of foreign affairs and then president of the United Nations General Assembly. The alleged bribes were made on behalf of a Shanghai-based energy company, which is not explicitly named in the court documents.

CNN emails and calls to the government of Chad went unanswered. Last year, the government of Chad said in a statement: "Faced with this umpteenth false allegation, the government of Chad formally refutes this shameful fabrication."

The government of Uganda has said in a statement that it was "erroneous" to say Kutesa was involved with the alleged bribery. Ho’s lawyer declined to comment, but his client has pleaded not guilty to the charges against him.

At times, court documents show, some people at the UN treated the NGO as an arm of the Chinese state.

For example, according to emails presented by prosecutors, Ho was asked by an associate to "intervene with the Chinese state" to provide Chad with military weapons to fight Boko Haram. In emails with other individuals, Ho also discusses passing on arms to Libya and Qatar and suggests that CEFC China Energy could help an Iranian company move sanctioned money out of China, according to prosecutors.

In a statement, CEFC China Energy distanced itself from the NGO, saying that the latter was "not involved in any of the commercial activities of CEFC China Energy." CEFC China Energy said it conducted its business activities "in strict accordance with the law."

A house of cards

In the end, no one gave CEFC China Energy the $9 billion to buy the stake in Rosneft. Two months after the deal was announced, Ho was arrested. It was the falling domino that would bring down Ye’s empire.

On March 1 this year, respected Chinese financial news outlet, Caixin, published an explosive forensic investigation into the finances of CEFC China Energy, alleging that the organization was a house of cards, precariously stacked on loans to cover loans. CEFC China Energy said the report "had no basis in fact." Days later, Ye was reportedly detained in China -- and he has not been seen since.

Industry analysts say there had long been whispers about the stability of CEFC China Energy, with experts believing the company did not have enough business to match its size.

The entire floor where one CEFC branch is registered at is empty. The management said it had never been occupied. CNN

One address of three registered CEFC related companies is a defunct office. CNN

"Accounting standards and corporate oversight is still pretty weak in China and there isn't a lot of transparency," says Tom Rafferty, a China expert at the Economist Intelligence Unit. "There are lots of issues in China around opaque corporate structures."

CNN contacted China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs about the relationship between CEFC China Energy and the Chinese government, Ho’s arrest in New York and the reports that Ye has been detained by the Chinese authorities. A spokesperson faxed back the following response: “I have no knowledge about the incident you mentioned. What I can tell you is, China is a country ruled by law, and the Chinese government has consistently asked Chinese enterprises to abide by local law and regulations when they operate overseas.”

Attempts to reach Ye for comment through his company were unsuccessful.

In Shanghai, CNN visited the registered addresses of eight CEFC China Energy subsidiary companies. None showed any sign of the company. Two locations were new office buildings which had never been rented out, while one was a state-owned bank. At one near-empty building, a sign carried a President Xi quote: "China's door to the world will never close, but only open wider."

CEFC is finally state-owned

Once a big buyer, CEFC China Energy is now a big seller -- its property is under the hammer, with a Chinese state-owned company taking control of many of its international assets.

Ye’s former Bel Air mansion in Pok Fu Lam, Hong Kong. Savills

Ye Jianming bought a two-bedroom apartment overlooking the United Nations. Newscom

In March, the Czech government sent a delegation to Beijing to find out where Ye had gone. Czech President Zeman said that Ye, who is still his economic adviser, was being investigated in China on "suspicion of breaking the law." Zeman’s spokesman tells CNN that if Ye “is found guilty he will cease to be an adviser to Zeman."

Ye's downfall comes amid a wider crackdown in China on debt-ridden private companies. Earlier this year, Wu Xiaohui, chairman of Anbang Insurance Group, which famously bought New York’s Waldorf Hotel for $1.95 billion, was arrested for fraudulently raising billions of dollars from investors. In May, he was sentenced to 18 years in jail by a Shanghai court.

“The government isn't happy about how they've been conducting their affairs, particularly if they've been using it to move their capital out of the country”Tom Rafferty, principal economist for China at the Economist Intelligence Unit

"The government isn't happy about how they've been conducting their affairs, particularly if they've been using it to move their capital out of the country," says Rafferty, of the Economist Intelligence Unit, regarding over-leveraged companies.

Two thirds of the company’s financing came from the state-owned China Development Bank. Today, Chinese state-owned giant CITIC has taken control of CEFC China Energy’s Czech assets. It's an echo of an earlier Belt and Road deal gone wrong, in which the Chinese government took control of a port in Sri Lanka when debts to a Chinese state-owned bank couldn't be repaid in 2017.

Meanwhile, the whereabouts of Ye are unknown -- and what charges, if any, he may face in China have not been publicly revealed.