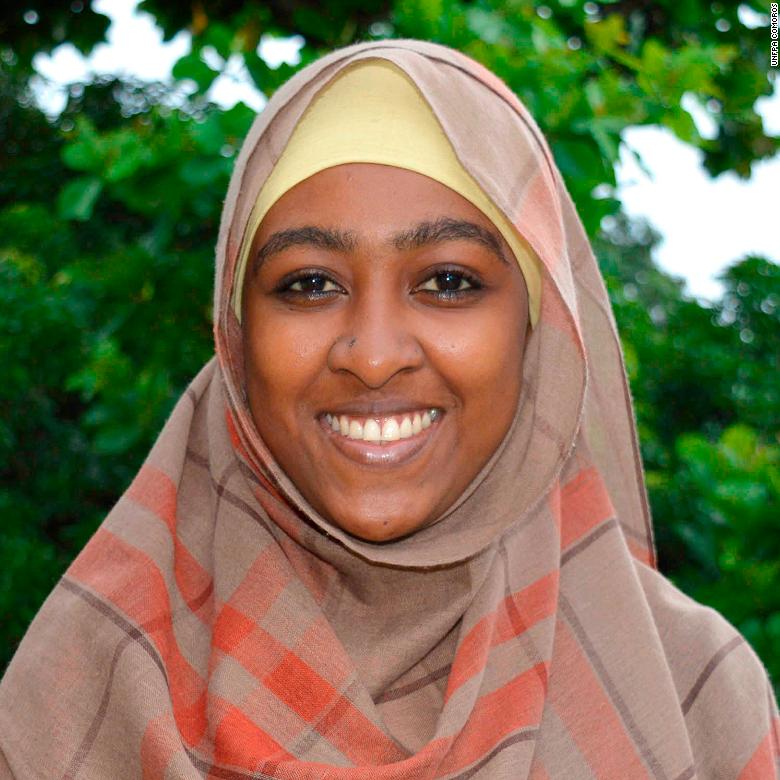

Takia Ali Mohamed Abdallah, 22

Takia Ali Mohamed Abdallah, 22

Grande Comore, Comoros

Takia Ali Mohamed Abdallah, 22, from the island of Grande Comore in Comoros, couldn’t wait to start school.

“I remember the first day of school, but especially the day before,” Takia said. “I wanted to see how it feels to wear new clothes and put a backpack on to go to school.”

Comoros, an archipelago of islands in the Indian Ocean off east Africa, is one of the world’s least developed countries, plagued by overpopulation, poor harvests and severe unemployment. Education is officially compulsory for children from 6 to 16, but a large portion of the country’s children receive little or no schooling. While 83% of girls enroll in primary school, compared with 88% of boys, that number drops to 45% in secondary school.

“I was very happy and did not stop smiling in the street because I was going to school,” Takia said, recalling her first day.

“Once at school, I was scared and shy to see all those children I did not know well dressed and some of them came from very rich families. They came with little toys and stuff that I did not have. Already some of them already spoke French and I did not know a word,” she added.

Only half of the population is literate in French, which is still the official language of government administration in Comoros decades after the islands gained independence.

— Takia told her story to UNFPA.

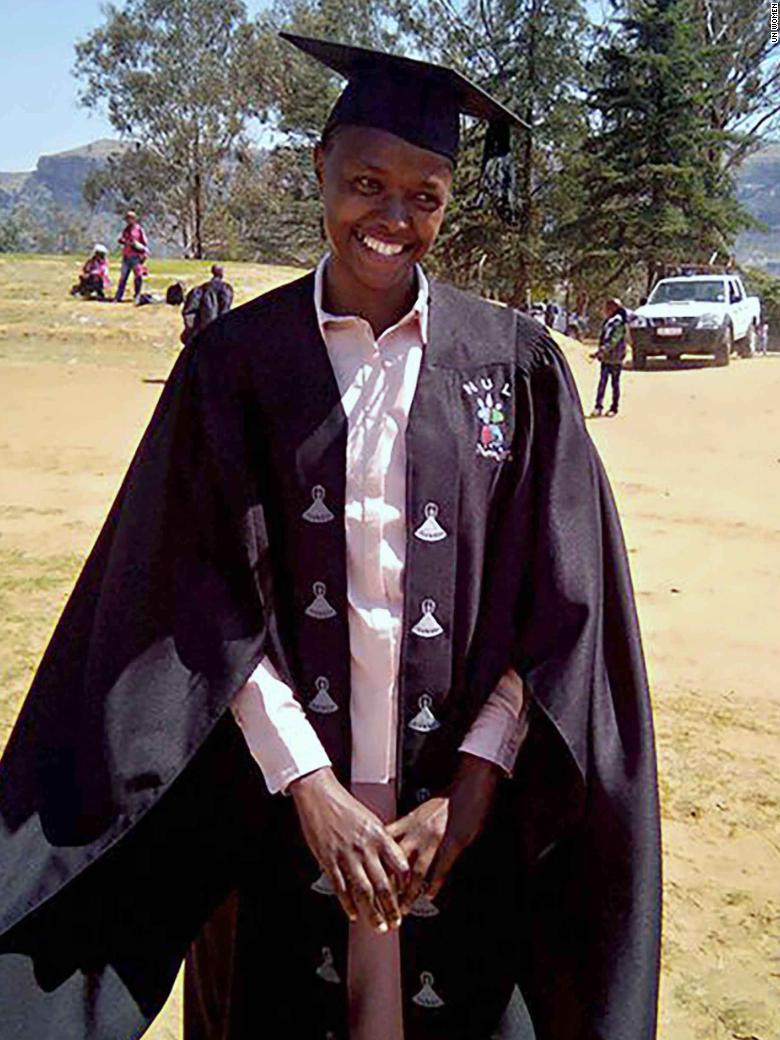

Lerato Seqhomoko, 32

Lerato Seqhomoko, 32

Leribe, Lesotho

In 1998, Lerato Seqhomoko had to leave school because her mother could not afford the fees. She ended up repeating grades eight and nine. In 10th grade, she got glaucoma and lost her eyesight completely. Lerato was out of school for five years.

“I wanted to go to school but didn’t know how,” Lerato, now 32, from Leribe, Lesotho, said.

It wasn’t until 2008 that Lerato went back to school, enrolling in St. Catherine’s Girls High School for the visually impaired on the recommendation of a local educator. “My first day … week … month was like a whole new world. I tried to make myself young but I was old. I was with 12-year-olds and I was 24! It was terrifying but perseverance kept me going. I told myself that I was there to take the opportunity.”

In Lesotho, a small country completely surrounded by South Africa, 42% of girls enroll in secondary school, about half of the number enrolled in primary school.

“The way you see things is different when you are educated. The ethics, principles and guidelines you learn are important. Education makes us mature,” Lerato said.

She recently completed a diploma in pastoral care and counselling with distinction at the University of Lesotho and plans to return in the next academic year to start a three-year degree in counselling. When she’s done with her studies she wants to work with children. “Many children are from poor families. I want to motivate them to go to school. Education is a priority. If you have a certificate, you have a better chance at life.”

— Lerato told her story to UN Women.

Brenda Pauline Gussin, 14

Brenda Pauline Gussin, 14

Buchanan, Liberia

“On my first day in school, I was happy because it was an opportunity for me to make new friends. What I remember most is the kindness of a girl who is now my best friend,” 14-year-old Brenda Pauline Gussin, from Buchanan, Liberia, said.

“As I entered the class in a raincoat under a heavy downpour, Mercy hurriedly walked to me to help remove the plastic jacket and showed me where to hang it. Mercy started school a day before me. Upon entering, the teacher asked all students who were in class for the first time to stand up and introduce themselves. When it was my turn, I stood up and could not say anything. My classmates started laughing at me and I burst into tears.”

Liberia’s education system was unstable for decades because of the civil war, during which many children were unable to ever start school. Today, 37% of girls enroll in primary school compared with 39% of boys, according to UNFPA. In secondary school enrollment falls to 15% of girls and 18% of boys, according to UNICEF. And this is reflected in the literacy rate -- just 37% of girls, compared with 63% of boys, aged 15 to 24 are literate.

“When you are in school, you experience a lot of things. You have the opportunities to learn, associate with others. School also prepares you for the future,” Brenda, who is now in the ninth-grade, said.

“When a woman is educated, she can positively impact the life of her family and her children. Once you are educated, you will be able to contribute to the development of your country. You will be well known in your country. When you are educated, you can also help other people.”

— Brenda told her story to UNFPA.

Dearest Walker, 15

Dearest Walker, 15

Monrovia, Liberia

“My first day in school was not fun. I was afraid of the unfamiliar environment,” 15-year-old Dearest Walker, from Liberia’s capital Monrovia, said. “I was too young to remember vividly. But one thing I can remember is that I chased after my mother after she had dropped me off.”

Now in 10th grade, Dearest loves school. “I like the fact that school is preparing me for future opportunities and challenges in a world where success is often defined by your level of education. My parents are doing everything to send me to (the) best school they can afford. That is why I am always eager to study my lessons. I always want to pay them back with good grades; something that makes me happy and also makes them proud of me.”

Today, 37% of girls enroll in primary school compared with 39% of boys, but that number drops drastically in secondary school to 15% of girls and 18% of boys. And this is reflected in the literacy rate -- just 37% of girls aged 15 to 24 are literate, compared with 63% of boys, according to UNICEF.

“When you are educated, you will not be easily toyed with. When a girl or woman is educated, she tends to be a pillar that her family can lean on. She can also fend for herself. People are going to respect you once you are educated,” Dearest said.

— Dearest told her story to UNFPA.

Lango Tarpilan, 26

Lango Tarpilan, 26

Careysburg, Liberia

Much of Lango Tarpilan’s childhood was affected by Liberia’s civil war, which robbed many in the country of an education.

Remembering her first day at a local community school run by the Catholic Church in Ganta, Nimba County, Lango said: “At that time, I couldn’t speak English well so I was very shy. My friends laughed at me when I tried to introduce myself or say something in class.”

“For the rest of the day, we played games and anyone who won received a mango as the prize. I think I won about two times and I got my prize.”

Now 26, Tarpilan has a 3-year-old son and is studying at the Pimah College of Nursing in Paynesville, outside Liberia’s capital Monrovia. She runs her own soap-making business on the side, which helps her pay school fees and take care of her son.

“When you are educated, especially for a woman, you are respected and empowered to advocate against some of the inequalities in society – otherwise, your life will be very difficult,” Tarpilan said.

— Lango told her story to UN Women.

Shelia Kidea Smith, 15

Shelia Kidea Smith, 15

Monrovia, Liberia

“On my first day in school, I was feeling kind of afraid, I thought I would never have anyone to play with,” 15-year-old Shelia Kidea Smith, from Liberia’s capital Monrovia, recalled. “For the first week, I was always by myself. Gradually, other students started coming around asking me to join them.”

Liberia’s education system is still recovering after years of instability during the country’s civil war. Today, 37% of girls enroll in primary school compared with 39% of boys, but that number drops drastically to just 15% of girls and 18% of boys enrolled in secondary school. This is reflected in the literacy rate -- just 37% of girls aged 15 to 24 are literate.

“School can give knowledge and wisdom. It can open up your mind to know to your rights, who you are; who you want to become. It helps to define your personalities and your contributions to society. It can change your way of thinking,” Shelia, now in ninth-grade, said.

“Education helps you to get a brighter future. My parents know this and this is why they are making so much sacrifice to send me and my brothers and sisters to school, even though times are hard. With good education, the sky can sometimes be the limit as you have the potential to explore the world and overcome challenges.”

— Shelia told her story to UNFPA.

Vanessa Juah Nimely, 18

Vanessa Juah Nimely, 18

Monrovia, Liberia

“My first day in school, I was very lonesome. I refused to let go (of) my mother after she had dropped me off,” 18-year-old Vanessa Juah Nimely, from Monrovia, Liberia, said. She’s now in 12th grade at Canterbury Episcopal High School. “While other kids were happily running around, some kept staring at me. I remember, my mother said to me: are you not ashamed that your schoolmates are watching you crying?”

In Liberia, 37% of girls enroll in primary school compared with 39% of boys, but that rate drops drastically in secondary school, with 15% of girls and 18% of boys enrolled. This is reflected in the literacy rate -- just 37% of girls aged 15 to 24 are literate, compared with 63% of boys.

“School lays the foundation for your future,” Vanessa said. “The main thing I like about school is that it provides you with the opportunities to interact with others from (a) diverse background.”

“Education is important because when you are educated, people won’t look down upon you. When you are educated, you will be able to do things for yourself - you will not depend on others for survival,” Vanessa added.

“I am going to school to learn. I believe with the best education that my parents can afford to give me, I will be able to take care of my family in the future and pay back my parents by caring for them in their old ages. I will also be able to contribute meaningfully to the development of my country and the world at large.”

— Vanessa told her story to UNFPA.

Soavy, 6

Soavy, 6

Atsimo-Andrefana, Madagascar

Soavy, 6, from Madagascar’s Atsimo-Andrefana region, just started school. The youngest of seven siblings, she’s been wanting to study for as long as she can remember.

"Since I was four years old, when I saw my brothers and sisters going to school, I accompanied them with my mother and I cried as soon as they entered the class because they left me alone. I told my mother that I want to study too and she replied that I am still small and can not go to class. I am now like them, I have my schoolbag and I am going to write.”

In Madagascar, 78% of girls and 77% of boys enroll in primary school, according to UNFPA. But that number drops in secondary school, with only 32% of girls and 31% of boys enrolled.

“On my first day of school I had my bag on my back and my mother let me in class. In the hallway, the children screamed and I looked at them. Finally, I cried as well as others,” Soavy said. “Today I do not cry anymore, I love to write and I like playing with my classmates. I would like to be a doctor one day, I say it all the time to my mom and she just smiles.”

— Soavy told her story to UNFPA.

Fostina Nkhoma, 19

Fostina Nkhoma, 19

Malenga, Malawi

“I was 6 years old then and it took me about 15 minutes to walk to Makankhula primary school,” 19-year-old Fostina Nkhoma, from Malenga village in Malawi’s Dedza district, said, recalling her first day at school. She remembers arriving without a uniform or notebook, not having eaten breakfast that morning.

“There were five of us from our village, Stella, Lonely, Mavuto, William and myself. Three are now married.”

Having missed several years when she became pregnant and dropped out of school. Nkhoma has since re-enrolled and is now in seventh-grade.

Very few girls make it to secondary school in Malawi, with only 33% enrolling. Many girls, like Fostina, drop out of school because of pregnancy or for marriage. This is often encouraged by parents, who can no longer afford to pay for school fees or supplies.

“I find education quite a good thing because I am sure some day, I will be able to support myself and become an independent woman,” Nkhoma says, adding that she’s determined to finish her education.

“You know, if you stay at home, you go to work in the garden every day and the heat makes you not look nice. For me, I take a bath every morning and walk to school and makes me still look younger than my friends of the same age but are married and work in the garden often, they look older than me,” she said.

— Fostina told her story to UNFPA.

Linda Kanenula, 18

Linda Kanenula, 18

Lilongwe, Malawi

Linda Kanenula, 18, has dreams of becoming a nurse. Now in her last year at Tsabango Community Secondary School in Lilongwe, Malawi, she said she will never forget her first day at the school.

“On the first day of school, my drama teacher wrote different characters on the board. She told us to act out the role of the character we had selected. I immediately chose to be a nurse. My teacher said I could be anything I wanted to be,” Kanenula said, adding that this motivated her to reach for more than a school certificate.

Last year, Kanenula was given the lead role in a school play for the first time. “The play was about ending child abuse at school and home. That play freed me,” she said.

Child abuse, sexual exploitation and child labor are serious problems in Malawi, particularly among girls, according to UNICEF. Very few girls make it to secondary school, with only 33% enrolling. Many girls drop out of school for marriage. This is often encouraged by parents, who can no longer afford to pay for school fees or supplies.

— Linda told her story to UN Women.

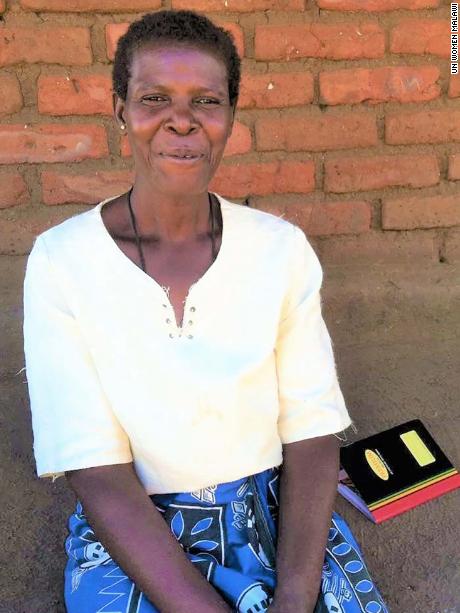

Loveness Moses, 72

Loveness Moses, 72

Nankumba, Malawi

Loveness Moses, a 72-year-old mother of 10, has just started school.

After attending a UN-supported session on women’s empowerment, Loveness was identified as a potential lead farmer in her village of Nankumba, in Malawi.

But she had to tackle another obstacle first: she couldn’t read or write.

Growing up, Loveness’ mother permitted only her sons to attend school, saying that girls should stay at home, tend the farm and look after the younger children.

“When I became a mother, I ensured that all of my 10 children, girls and boys alike, attended and completed primary and secondary schools,” Loveness said.

On her first day at an adult literacy classes last year, she was nervous but excited. “I was surrounded by other mothers, fathers, grandparents who had a hunger to learn,” she said.

Now she’s qualified to become the first female lead farmer in her village, where she is a champion of gender equality and an advocate for education. When asked how learning makes her feel she said, “It makes me feel so good that I never ever want to stop learning.”

— Loveness told her story to UN Women.

Martha Katola, 17

Martha Katola, 17

Mikute One, Malawi

On her first day of primary school, Martha Katola, now 17, remembers walking the five minutes from her village in Malawi’s Salima district and arriving without a uniform or packed lunch.

“When I came to school, the head teacher asked me to put my hand over my head and touch the ear on the other side of the head to check if I was at the appropriate age to start school. I did not manage but he let me in,” she said.

Martha, now in form three at Parachute Community Day Secondary School, is the second child in a family of five. She wants to be a soldier when she finishes school.

“I have learned to sew sanitary pads and also made new friends in the course of my education” she said.

“These days, even in marriages, education is vital for the two of you to make good decisions about the family.”

— Martha told her story to UNFPA.

Promise Kamanga, 18

Promise Kamanga, 18

Ndilowelo Village, Malawi

“I wore a red dress on that day,” Promise Kamanga, an 18-year-old from Kambwiri in Malawi said, recalling her first day of school.

“I was excited to go to school after having a long chat with my sister of what school was like, and I looked forward to this day.”

She remembers meeting her first friend at school, Gloria, and playing a game called “champi” at break time.

Now in eighth-grade at Katelera Primary School, Promise’s favorite subjects are English and mathematics. She wants to be a journalist when she completes school.

“School creates an opportunity for me to make good friendships and learn different talents,” Promise said.

Promise added that she hopes to finish school and become a role model to other girls in her community.

Only 33% of girls enroll in secondary school in Malawi. Many girls drop out of school because of pregnancy or to marry. This is often encouraged by parents, who can no longer afford to pay for school fees or supplies.

— Promise told her story to UNFPA.

Lily, 7, and Beatrice, 7

Lily, 7, and Beatrice, 7

Quelimane City, Mozambique

Lily and Beatrice, both 7 years old, just finished their first year in school in Quelimane city, Mozambique.

They said that they learned the vowels in the alphabet and how to count to 20. They also said they sang and danced in school, breaking into a singsong about a doll.

The girls appealed to children not yet enrolled in school to attend, saying that they would like to teach them how to recite their vowels too.

While primary school enrollment is high for both boys and girls in Mozambique, many students drop out in secondary school, with only 18% of girls and boys enrolling, according to UNFPA. Child marriage and early pregnancy are often a contributing factor in forcing girls to quit school. In a 2015 survey by Mozambique’s health ministry, 46% of girls 15 to 19 years old were either pregnant or already mothers.

— Lily and Beatrice told their story to UNFPA.

Keza Chantal, 9

Keza Chantal, 9

Minazi Village, Rwanda

“I started school at an older age compared to others due to lack of school materials and fees,” Keza Chantal, 9, from Minazi Village in Rwanda’s Northern Province said. Keza, who will be entering fourth-grade in the 2018 academic year, is one of seven children. Her father works in construction and her mother is a housewife.

“The new uniform that my parents afforded to buy for me was an exciting thing. I always heard my elder sister joking around that my uniform is very long that I will wear it for many years. I guess my parents couldn’t afford buying new pairs regularly for all of us at home but I just loved it!”

Keza described her first day of school as a “relief.”

“I went to bed dreaming of the adventures that would take place the next morning. It was very early morning when my mum and I started the journey to school. I don’t remember how long we walked but I was excited to leave home as it was a relief from heavy work, including fetching water,” Keza said.

“When we reached school, my mother talked to the teacher but I didn’t pay much attention to their conversation. I guess it was about school fees and materials that they couldn’t pay at the beginning as they had many children to look after back home. She handed me to the teacher. I watched my mother’s back until she disappeared.”

When it comes to equality between men and women, Rwanda, one of world’s least developed countries, was ranked as the fourth-best globally by the World Economic Forum in 2017. The country has made big strides in promoting gender equality, promoted by the government. And this has shown in its educational representation. In Rwanda, 95% of boys and 97% of girls enroll in primary school.

— Keza told her story to UNFPA.

The As Equals reporting project is funded by the European Journalism Centre via its Innovation in Development Reporting Grant Programme. Read more stories like this.