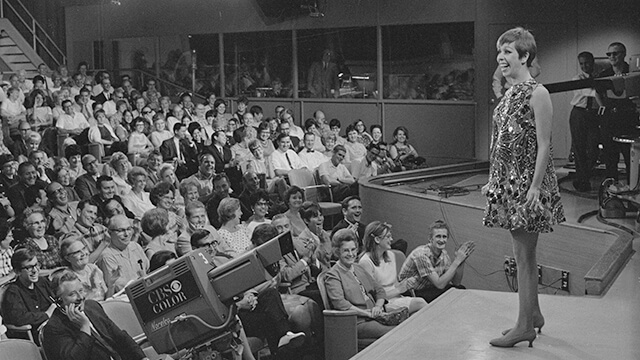

To highlight iconic work by women in television, CNN presents a conversation about strength, authenticity, seeing and being seen. Memorable characters, great stories -- As Told By Her.

Joan Clayton feels a little underdressed for the scenario in front of her. Her boyfriend has surprised her with an elaborate marriage proposal, but she's wearing the universal uniform of comfort -- Ugg boots, a soft cardigan and her glasses. She smooths down her hair with her hands, and as she removes the round frames from the bridge of her nose, her vision blurs. At the request of her boyfriend, Joan puts her glasses back on because he doesn't want her to miss any part of the special moment.

In that scene, "Girlfriends" delivered an engagement seven seasons in the making along with a powerful image: Joan, played by Tracee Ellis Ross, dressed for comfort and fully embraced as she is.

"I had to speak up for those sort of things," "Girlfriends" creator Mara Brock Akil remembered recently this summer during a candid conversation with female actors and producers at the ATX TV festival in Austin, Texas.