Why can't we all get along?

Why can't we gather round the fire and sing Kumbaya like our forefathers?

Why can't we make America harmonious again?

That's easy. We can't.

Because we never could.

We can't because it never was.

"One of the characteristics of Americans is that we don't have a good sense of our history," Colin Woodard tells me as we stroll Manhattan's High Line park. "We don't know our past. And that leads to all kinds of problems."

"We the people" included puritanical English, libertine French, Scotch-Irish brawlers, Caribbean slavers and pacifist Quakers...

Colin is an award-winning journalist and author and his books "American Nations" and "American Character" are brilliant reminders that by the rules of human nature, this country is an impossible experiment.

Humans are tribal creatures. We are naturally most content when surrounded by people who look, think and pray the same as we do.

America is a 241-year-old argument between people who look, think and pray in every possible variation.

"We the people" included puritanical English, libertine French, Scotch-Irish brawlers, Caribbean slavers and pacifist Quakers and this continent is an accidental, real-life "Game of Thrones;" built by people with very different definitions of "liberty and justice for all."

And the key thing is they didn't know that they were all going to be part of the same country!" Colin laughs. In "American Nations," Woodard redraws the map according to cultural values and immigrant streams. When he strips away familiar borders, the 50 United States of America become the 11 Divided Nations of America.

The land from New England to the upper Midwest he calls "Yankeedom," founded on a Puritan's passionate belief in teamwork. "They were coming on a mission to build a more perfect society on earth, that shining light on the hill and they were going to do it as a community and the individuals had to get on board with the program."

For these early Americans, the first thing they did after getting off the ship was to divvy up the land in lawyerly fashion, chip in to build a school and meeting house and build a society around the belief that We're All In This Together.

"So there's more trust in government because it's supposed to be an extension of ourselves," Colin explains. "Those are all things that are not true of other regional cultures, and in fact, are anathema to them, and in the historical experience of other regional cultures, wouldn't make any sense."

In fact, this kind of trust in authority made no sense to the people who first settled western Pennsylvania and spread the "nation" of "Greater Appalachia." These were Scots-Irish fighters and fiddle-players right off the set of "Braveheart." "Places where there was constant warfare for generations and generations, where if government came, it was usually in the form an army with lances trying to mow down your family. And they tended not to be farmers but herdsmen, so people can steal all your valuables very easily."

Their knee-jerk instinct? Get Off My Land. Unlike the folks in Yankeedom, these new Americans built self-reliant clans, wary of outsiders and downright resentful of far-away government.

This set up an intercontinental tension between "We're All In This Together" liberals vs. "Get Off My Land" libertarians.

Sound familiar?

"It's not just abortion," my friend Ralph says as he explains his vote for Trump. "For me, it's a bigger government, small government argument."

We're sitting in a Tulsa backyard, surrounded by some of the most generous people I know. They believe it is their Christian duty to give time and money to people in need, near and far. Ralph builds homes for the poor in Central America and works for a company with a "giving motive" instead of a profit motive.

But he is also the product of "Greater Appalachia," where they bristle at the idea of powerful people far away telling them what to do. "The bigger the government gets, the less control we have in our own life," Ralph says with a shrug.

If that is a guiding principal, deep in the cultural DNA, it becomes easier for a Christian to vote for candidate who is nothing like Jesus.

The not-so-Great Divide in Trump's America is only going to get worse. Unless we realize that we are all from different, but vital American nations.

You may think that the borders of these cultural nations would fade over the centuries, as "The Bachelor" and Applebee's turns us into homogenized American mush. But the differences are actually getting more dramatic as Americans sort themselves by values.

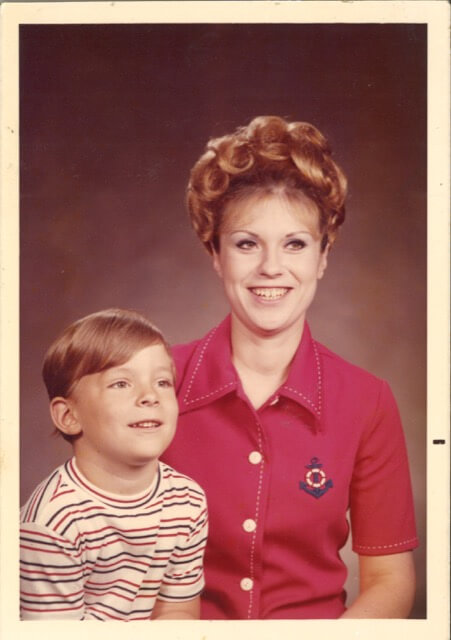

When Mom left Yankeedom Milwaukee to live among Evangelicals in Greater Appalachia, she was part of a trend that shows up in red and blue maps after election day. It's why Thanksgiving becomes so fraught with tension after Junior moves to the Big City and can't fathom how Mom and Dad could possibly vote for X.