City of the Dead

A neighborhood destroyed by Duterte's war on drugs

- By Euan McKirdy, Pamela Boykoff & Will Ripley

- Photography by Linus Escandor II

The following story contains images that may be disturbing for some readers.

Chapter 1

A child's funeral

Maria Musabia slowly walks behind the two white coffins — both cheap, one cruelly small — as they make their way to a shallow trench. The 68-year-old grandmother dabs her eyes with a towel. The caskets are opened for one final viewing, and her body convulses with grief.

This is the last time she will see their faces.

Her 5-year-old grandson, Francisco, is lowered into the earth. Two plastic toys, still in their boxes, are placed on top of the coffin, and the dirt is hurriedly shoveled over. His fragile body will rest in this spot on the side of the cemetery’s path because the cost of a proper plot was too high.

A chick is placed on Francisco's coffin — a Filipino burial custom used for murder victims. The bird's pecking on the glass of the coffin symbolizes the eating away of the murderer's conscience.

Buried alongside the child this same day is Maria’s son, Domingo Mañosca. He was a 44-year-old pedicab driver and an admitted meth user. He was killed in his home for being an alleged drug dealer – something his family denies.

He was also Francisco’s father.

Santo Niño is a poor neighborhood in Pasay City, one of the 16 cities that make up the National Capital Region, also known as Metro Manila. More than 4 million people live in slums like this one. Jobs are scarce, and the community suffers from a lack of sanitation, clean water and adequate, safe housing.

When the killings first started here, a local reporter called it “Patay City" — “City of the Dead."

From Santo Niño's main thoroughfare, it takes just a few turns down trash-strewn alleys to reach the tiny apartment. Up three flights of unsteady stairs is the ramshackle room that Domingo and his family called home.

His partner, Elizabeth Navarro, is not just a widow. At 29, she’s now a mother who knows the pain of losing a son. When we meet, she is heavily pregnant with her fifth child.

It’s two days before Christmas. Here Elizabeth stands, rocking her infant daughter, who is restless and sweaty. A single strand of tinsel hangs from a nail, twisting in the air. Eight people once slept in this home. Now only six do.

This is where it all happened.

Elizabeth remembers that evening earlier in December. Domingo was trying to fix the DVD player when, from the darkness, gunfire tore through the plywood they used as walls. Domingo was killed. Another bullet struck Francisco in the forehead as he slept nearby. Their murders remain unsolved.

Domingo and Francisco are just two of more than 7,500 drug-related deaths that the country has endured over the past six months, according to the Philippines National Police statistics. It’s part of the bloody fallout from Duterte’s war on drugs.

In recent weeks, after crooked cops killed a South Korean businessman, Duterte has called for a total overhaul of the Philippines National Police.

“Cleanse your ranks. Review their cases. Give me a list of who the scalawags are," he said in a press conference at the end of January.

Duterte won the presidency last May after running a campaign focused on law and order. He promised to rid the country of its drug problem — mostly methamphetamine, known locally as “shabu” — by any means necessary. He told users and drug-pushers: “If you really destroy my country, I will kill you.”

Santo Niño has seen its share of death. The war on drugs came early to this “barangay” — the Tagalog word for neighborhood — with the murder of Michael Siaron. His death in July made national news when his wife was photographed holding his lifeless body in the street. Now, the neighborhood has had to confront the murder of a child.

Despite the unsolved murders that Manileños see splashed across their daily newspapers, Santo Niño residents say their streets are safer now. The drug-pushers and users who once plagued this area, and so many others like it, have been removed — jailed, killed or forced back into the darkness.

But, as families of victims caught up in this deadly crusade have discovered, this sense of safety comes at a cost.

Domingo was an admitted user of shabu, which many poor Filipinos use to ward off hunger. Others use it to push their bodies through extended hours of physical labor — the kind of work many pedicab drivers like Domingo endure every day.

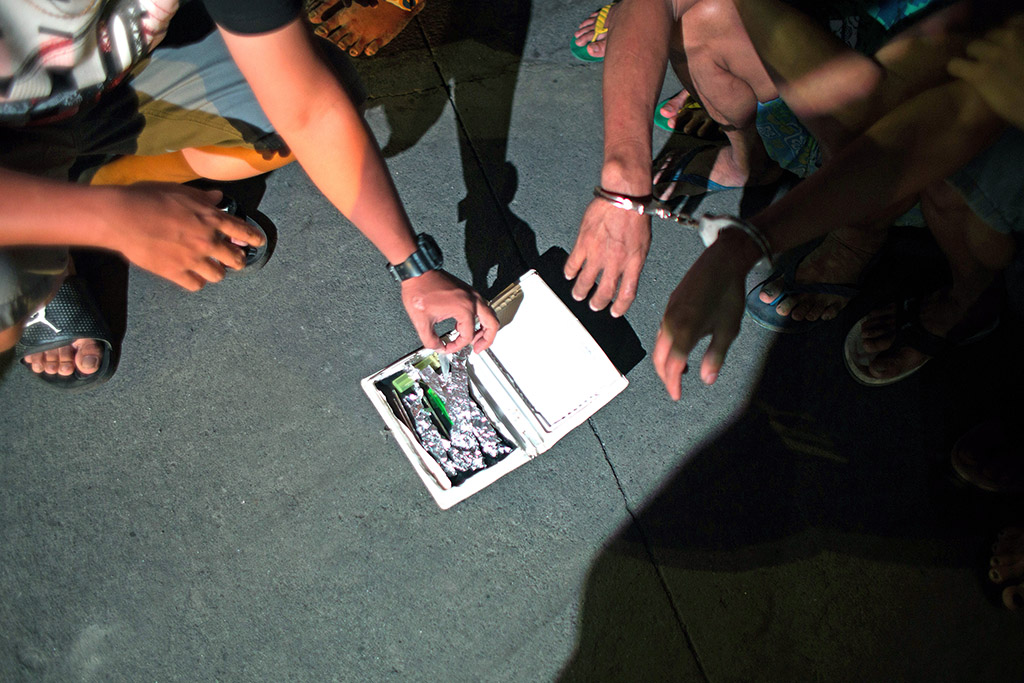

Domingo registered as a user under the controversial “tokhang” anti-drug drive — also known as the “knock and plead” campaign, which is designed to identify drug users. It also allows police to request they register with the local authorities. So far, the police say around 1.2 million Filipinos have registered. Those who sign up are supposed to receive government-supported rehabilitation, but many say it is insufficient or non-existent.

Opponents say the procedure — users are photographed, interviewed, fingerprinted and required to pledge that they will no longer use drugs — is little more than a de-facto arrest. Most poor residents, who lack education and access to information, are unaware they can refuse registration.

Maria says she knew Domingo had previously used drugs but maintains that he wasn’t dealing, as was reported in local media.

In any case, the anti-drug registration campaign didn’t save Domingo. It may have actually brought him to the attention of his killers.

The impunity that those going after the dealers and users appear to have — despite deaths from police action and thousands of other vigilante killings — prompts little more than weary resignation from Maria.

“I have nothing to say about Duterte,” she says. “Even if we get angry there’s nothing we can do. We couldn’t get mad because the people voted for him.”

Duterte has vowed to execute 100,000 criminals and dump them into Manila Bay, and he’s suggested that he has killed before.

Shortly before assuming office, in a nationally televised address, Duterte also appeared to support vigilantism.

“Please feel free to call us, the police, or do it yourself if you have the gun ... you have my support,” he said. “Shoot him, and I’ll give you a medal.”

But Elizabeth feels that Duterte has been focusing on the wrong people.

“He should have first run after those who are making (the drugs),” she says. “There will be no drug users if there is no one selling and making it.”

A cellphone video shows Francisco balancing a coin on his forehead, laughing as he goofs around, mugging for the camera. He’s full of life.

Maria smiles sadly as she watches this artifact of her grandson’s life. “He’s alive … he’s alive,” she says.

Now that the funeral is over, Elizabeth is focused on her new child.

“Right now my only concern is the delivery (of the baby). I don’t want to think anything (more) about it.”

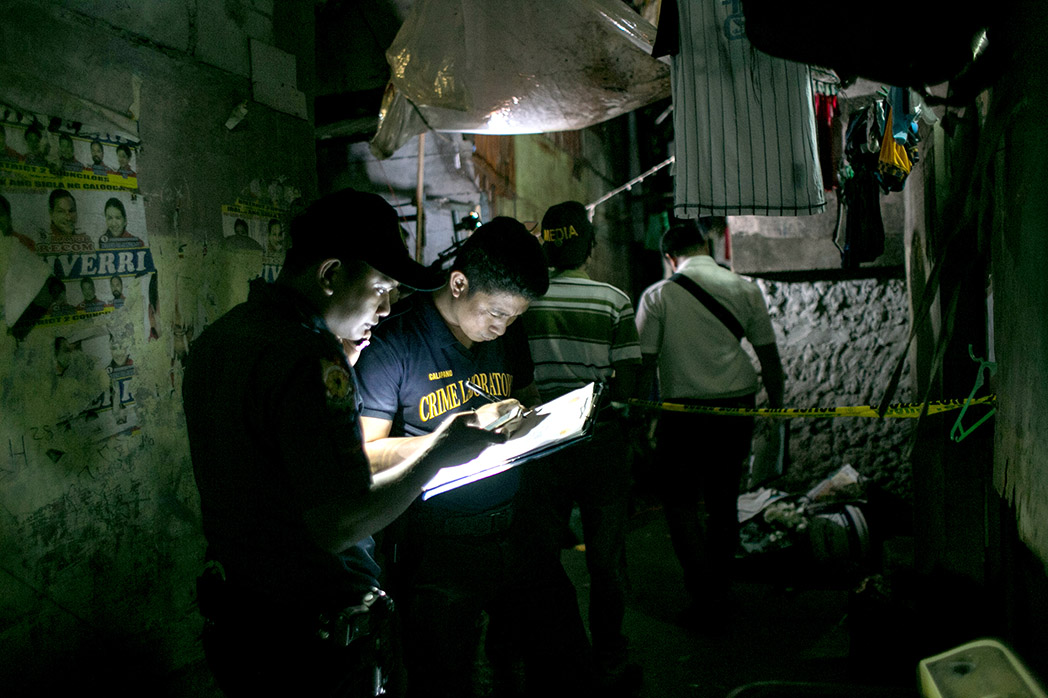

The Philippines Commission on Human Rights (CHR), which operates independently from the administration, looks into cases of rights abuse. It's part of the Global Alliance of National Human Rights Institutions (GANHRI). While it receives funding from Duterte’s government, the HRC is no friend of the president and has opened numerous files on suspicious deaths in his war on drugs.

HRC has visited the family’s home in an attempt to file a case for the slayings. But the family has refused out of fear.

“We don’t know who killed my husband. Better we keep quiet —we don’t want them to come back for us,” Elizabeth says. The safety of her family, she feels, is dependent on her silence.

However, a report has been filed for the family under a Philippine law that allows investigations to be submitted on the victim’s behalf, according to HRC investigator Jun Nalangan.

“We have a certain suspect, a policeman in Pasay City. We will (follow up) the investigation on said policeman,” Nalangan later told CNN via text message. Due to the family’s refusal to cooperate, the HRC says the case is progressing at a snail’s pace.

He says Domingo’s fate was likely sealed when a pusher who was in custody pointed to him in an attempt to extricate himself. It’s called “palit ulo” — “exchange head” — when a suspect is freed if he agrees to tip off authorities to a bigger fish.

Once Domingo was implicated — falsely, Nalangan believes — the pedicab driver likely became known to authorities, and through them, to his killers.

The PNP has not directly responded to CNN requests for comment. But in a statement after the South Korean businessman’s death, it did pledge to rid the force of “rogue cops.”

The Philippines National Police say overall crime is down in the drug war’s first six months, even as the murder rate soars. Polls show most Filipinos support the war on drugs, despite the rising body count. Recent figures from the PNP show that while overall crime rates are down 13.48% for 2016 compared to the previous 12 months, the murder rate has increased by 18%.

Chapter 2

The graveyard

As Maria buried her son and grandson that day, Ricardo Medina watched from nearby.

Ricardo, a caretaker at the Pasay City Cemetery, understands their pain better than most. It’s been less than two months since he buried his own son, Ericardo.

Ericardo was stabbed numerous times and his face was wrapped in packing tape, a grisly MO of the vigilante killings.

Domingo and Francisco are buried just dozens of yards from Ricardo’s own son.

“I buried my son in the grave that was meant for me,” Ricardo says. It was supposed to be a shared plot with his wife, who died in 1998. They gathered her bones in a sack and pushed them to the back in order to make room for Ericardo’s body.

Ricardo’s face is worn with grief, age and grinding poverty. He suffered a stroke about a year ago, but is too poor to even think about retirement. He’s 68 and has worked at this cemetery for 50 years.

He also lives in this cemetery, amongst the tombstones, with his second wife. In a space in between two walls of stacked graves, each about four levels high, Ricardo and his wife live with their dog and some of his surviving children — he’s had 18 in total, including Ericardo.

The cemetery provides somewhere dry to sleep and a place to store their meager possessions — a small portable TV, a stuttering fan and some worn clothes and shoes.

Ericardo worked as a barker. Most often young men, barkers are informally employed to call out the numbers and destinations of bus-like jeepneys – the ubiquitous workhorses of this packed, teeming city’s public transport system.

The night he was killed, Ericardo was out drinking with his friends, according to his father. Even though Ericardo died the death of a dealer, Ricardo insists he wasn’t part of the drug trade.

“He wasn’t a pusher,” he says.

Ricardo says he hates drugs and doesn’t use shabu himself. But he says he’s appalled at the way Duterte has prosecuted drug offenders. Other men who work in the cemetery are outspoken Duterte supporters, he says, and he doesn’t mix with them.

Ricardo worries any time his kids go out after dark. “I’m old, and I’m afraid,” he says.

The morning after his son was murdered, Ricardo recognized footage of Ericardo’s body on the local news because he had a forearm tattoo bearing the family name. Ricardo asked his other children to go fetch the body and bring him home to the cemetery.

“I haven’t asked the police about his death … We have nothing to do. He’s already here,” he says, pointing to Ericardo’s burial spot.

Ericardo’s tomb is no more than 10 yards from his father’s home. It’s unpainted concrete, above ground. The plaque is simple: ERICARDO MEDINA – Jan. 18, 1993 to Nov. 16, 2016. Below is his mother’s name, Yollanda, who died nearly 20 years ago.

In this same cemetery is the so-called “Duterte compound,” a morbid nickname for a wall of graves with photos of fresh-faced young men, some barely out of their teens.

The compound is where Michael Siaron’s body lies, in a third-storey plot painted white and marked with the standard grave plaque. The cause of death isn’t given on these simplified memorials, of course, but the epithet speaks volumes.

Here are Pasay City’s victims of Duterte’s drug war.

Chapter 3

Mixed blessings

After its residents have finally retired for the night, Santo Niño is quieter – but only just.

What seems like a half dozen roosters crow, as reliably as metronomes, through the darkness. Throaty barks from dogs echo over the jumbled rooftops of shelters made of concrete, plywood and corrugated iron.

Though Santo Niño has declined in social standing over the years, it remains a lively, friendly and tight-knit community.

But like many poorer neighborhoods in Manila, it has felt the impact of illegal drugs, especially since Duterte took office.

“Boy,” a drug user who asked CNN to withhold his real name, says the feeling when you’re hooked is hard to explain. “It runs through the veins. It becomes a habit. The body just craves it.”

Boy spent three months in jail on a drug charge before Duterte came to office. These days, the stakes are much higher.

The neighborhood, which is a little over half a square kilometer in size, has seen at least six drug-related killings since the war on drugs began, according to barangay secretary Rey Legaspi. However, residents claim the number is higher.

Legaspi knows the Mañosca family. He says he “scolded” Domingo for his drug use, and tried to get him to go straight. He also knew Francisco and says killings like his have left many spooked.

“A lot of (residents) are afraid,” Legaspi says. “They are afraid that innocent civilians who are living in the community will get hit.”

For the sake of safety in his barangay, Legaspi says he’s satisfied the crackdown is working. But he’s “frustrated” that the extrajudicial killings aren’t being “resolved.”

Legaspi plays his part as an administrator, leading nightly patrols of volunteers around the neighborhood. He stops residents from drinking on the street and would police visible drug use if he still saw it.

Even though his own friends have died as a direct result of the anti-drug campaign, Legaspi says he trusts Duterte’s big picture.

Is Legaspi himself afraid? No, he says. “Because I’m not doing anything wrong.”

But neither was Francisco Mañosca.

Dotted amongst Santo Niño’s market stalls are tiny, wire-fronted “sari sari” shops — slum convenience stores that sell drinks, snacks, candy and cigarettes.

As dusk falls on Santo Niño and the lights flicker on, the neighborhood buzzes with a hum of activity.

At his store on the main drag, 56-year-old owner Benjamin Gallardo watches the neighborhood go by. “It’s a strong community,” he says.

He says the crime scenes from the vigilante-style murders in Santo Niño are nightmarish: faces bound in packing tape, dumped on the side of the road, crude cardboard signs proclaiming their alleged crimes left propped up on the bodies.

But Gallardo is skeptical of authorities’ claims that the police aren’t involved in the deaths. He says he doesn’t know if the police will even bother to try to solve the killings.

A recent Amnesty International report on the war on drugs alleges “unlawful and deliberate killings carried out by government order or with its complicity or acquiescence.”

“Some killings by unknown armed persons appear to be the result of fighting between and within drug gangs,” according to the report.

“Other cases, however, have a direct link to the police, with police officers either hiring paid killers to kill specific individuals or disguising themselves and carrying out the killings.”

Presidential spokesman Ernie Abella denied the allegations in a statement.

“The extrajudicial deaths are not state-sanctioned. This is also the conclusion of the Senate’s Committees on Justice, and on Public Order and Illegal Drugs. Their joint investigation of deaths during police anti-drug operations shows there is no state-sponsored policy of extrajudicial deaths and that there is relentless effort on the part of the PNP to carry out the campaign properly and within legal processes.

“Reforms in the PNP will rid the force of rogue cops.”

AJ Dunpa, who owns the Allan shop across the street from Gallardo, says the neighborhood was unsafe before Duterte took office.

“There was a lot of crime. They were arresting some addicts.” His own cousin is in jail on drug charges.

“There was a shooting, right over there,” he says, gesturing across the busy street.

But crime is in decline. As early as July, just months after Duterte took office, the Philippines National Police reported that the crime rate in the country had dropped drastically.

The murder of Francisco, AJ says, was a tragedy. But he can’t argue with the change in the neighborhood. Before the crackdown, he had to close his small business at 10 p.m. Now the store is open all night.

“It’s so sad,” he says. “I feel sorry for them, but what can we do?”

Chapter 4

La Pieta

The shack Michael Siaron shared with his partner Jennilyn Olaryres stood teetering on stilts over a stagnant canal choked a thick, stinking layer of garbage. It was a precarious living situation, but one the impoverished couple had to endure.

The home is gone now, torn down and replaced with hastily built concrete walls.

Last July, Jennilyn hurried alongside the “creek,” as it’s known here in Santo Niño, to the nearby Pasay Rotonda, a traffic interchange about 15 minutes from their home by foot.

What she saw there, and how she reacted, arguably became the face of the Philippines war on drugs. Ignoring the yellow police tape and the crowd huddled around her husband’s corpse, she fell to her knees and clutched Michael’s body against her chest.

In the image — now known as the Philippines’ “Pieta” photograph, a nod to the Michelangelo sculpture of the Virgin Mary cradling Jesus’ body — Olayres’ grief is quietly etched on her face. A handwritten sign near Siaron’s corpse reads: “drug pusher huwag tularan” — “I am a drug pusher, don’t imitate (me).”

He was killed by unidentified gunmen on motorcycles — one rider, and one gunman on the pillion seat in a tactic known as “riding in tandem.”

Jennilyn has insisted that Michael was just a pedicab driver who had no ties to the drug trade.

Duterte has shown little sympathy for the grieving woman and her murdered partner. Instead, he used the notorious image as a warning.

“If you don't want to die and get hurt, don't pin your hopes on priests and human rights (groups). They can't stop death," Duterte said. “Then you end up sprawled on the ground and you are portrayed in a broadsheet like Mother Mary cradling the dead cadaver of Jesus Christ. Well, that's very dramatic."

Michael’s body now lies in the cemetery’s Duterte compound. Jennilyn left the neighborhood shortly after his death and has been unreachable ever since.

But the couple who helped draw the world’s attention to Duterte’s war will never be forgotten here in Santo Niño.

Epilogue

Elizabeth Navarro’s fifth child, Frank Dominik Mañosca, was born in early January. He’s completely healthy.

Francisco will never meet his little brother, born a month after his death. His father, who was trapped in a cycle of drugs and poverty, will never know his new son.

The Philippines is one of the poorest countries in Asia. In 2014, there were 10 homicides per 100,000 people — similar to Russia, Uganda and Costa Rica, according to World Bank statistics. But the murder rate has risen dramatically since Duterte took office. One lawmaker described it as “open season” on those involved in drugs.

As innocent people are increasingly caught in the crossfire, a growing number of Filipinos are questioning the true cost of their leader’s crusade.