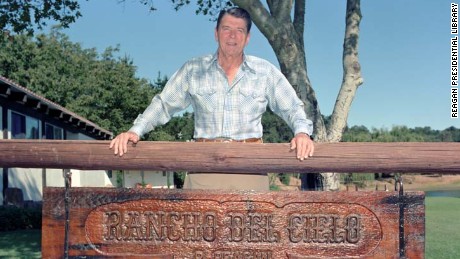

- Reagan's

ranch - Mount

Vernon - The

Hermitage - Wilson's

house - The 'Texas

White House'

How Woodrow Wilson pulled off 'an exceedingly difficult stunt'

On November 10, 1923, President Woodrow Wilson stood in his dressing gown in his dark-paneled library, swallowed his anxiety and prepared to execute “an exceedingly difficult stunt” — the first live, remote, nationwide radio broadcast.

Washington (CNN)

At 8:28 p.m. on November 10, 1923, President Woodrow Wilson stood in his dressing gown in his dark-paneled library, swallowing his anxiety and preparing to execute "an exceedingly difficult stunt."

That stunt, which he described in a letter to his friend Bernard Baruch, was the first live, remote, nationwide radio broadcast.

At that time, Wilson's four-minute address lamenting America's decision to withdraw "into a sullen and selfish isolation" after World War I was at the vanguard of technology. Though out of office and in chronic pain following a stroke, Wilson was determined to use every form of new media at his disposal to persuade the country to reverse course and join the fledgling League of Nations.

Ninety-two years later, the nation is in the midst of a presidential campaign largely defined by social media. Our most prominent politicians are once again wrestling with America's proper place in a chaotic world. And those politicians are promoting their messages through new media, showing off their communication prowess (or sometimes unintentionally, lack thereof) on Snapchat, Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

A fast-paced presidential race waged in the moment also offers an opportunity to turn backwards -- a chance to explore stories of presidents who came before, places that they loved and moments that defined them.

Wilson is the only president to remain in the nation's capital after leaving office. He moved into the stately house at 2340 S St., NW, at noon on March 4, 1921. Unlike most other presidents, he had no family home to return to and not much money. His friends felt that a former president should achieve a respectable standard of living, so 10 of them pitched in $10,000 apiece to help him pay for the $150,000 property. The president's $50,000 Nobel Peace Prize covered the rest.

About this series

Presidential Places is a weekly series on past presidents and places they loved. Over the next five weeks, we'll take a look at iconic presidential sites from Mount Vernon to LBJ's ranch.

Wilson pushed hard during his presidency for a lasting peace. He stayed in Europe for six months negotiating the Versailles Treaty at the end of World War I and campaigned across the country for the League of Nations when he returned, collapsing after a speech in Pueblo, Colorado, on September 25, 1919. The stroke he suffered when he returned to the White House left him debilitated and largely in seclusion for the remainder of his presidency.

Wilson's deepest disappointment was that his opponents in the Senate rebuffed his efforts and refused to approve U.S. membership in the League. Despite his poor health, he continued to advocate for participation in the League of Nations after he left office, even allowing Baruch's daughter, Belle, to persuade him to give the radio address.

Wilson appreciated the technological advances of his era: He was a contemporary of Thomas Edison's and went to college without electric light. The movie screen that hung in his library was a gift from Hollywood stars Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, and he often watched shorts to unwind before bed. His Victrola stood outside the library and played his favorites: Enrico Caruso, John Philip Sousa and the lively sounds of the music halls.

"President Wilson was what we call today an 'early adopter of technology,'" said Robert Enholm, executive director of The President Woodrow Wilson House. "But he didn't benefit from radio while he was president. Radio still had not reached the point where you could credibly reach an audience with radio of any size."

The technology advanced a few years later.

On the morning of November 10, radio technicians arrived early to start wiring Wilson's house. The President was anxious all day and spent most of the afternoon in bed with a headache, his biographer A. Scott Berg recounts. His wife, Edith, saw his stress mount in the two weeks before the speech and urged him to back out, but he refused.

Just before 8:30 p.m., Wilson came downstairs in his dressing gown. He was nervous about speaking into the microphone without an audience present and insisted on standing, accustomed to giving speeches on his feet. His headache had exacerbated his already failing eyesight, so Edith sat nearby to help if he needed prompting.

"Stations in Washington, New York and Providence carried the speech, which reached across most of the nation," Berg writes in "Wilson." "Some towns installed speakers in their civic auditoriums to simulate the collective experience of a live address."

The New York Times estimated that millions of people may have heard it.

"For the first time, a large number of American people were able to hear a senior official speak to the public," Enholm said. "It's said that the broadcast ... was able to be heard by a majority of Americans."

But the listeners weren't present in Wilson's home. And the president, an accomplished orator, struggled with the unfamiliar medium and no audience to energize him.

"The affairs of the world can be set straight only by the firmest and most determined exhibition of the will to lead and make the right prevail," he told his listeners in an eight-paragraph address.

He spoke slowly, deliberately, steadily -- sounding determined, and also a bit nervous. At the conclusion of the speech, Wilson felt deflated.

"When he was done, he had no sense that it went well," Enholm said. "He was sort of crestfallen about it."

The next day, Armistice Day, however, the public response was overwhelming. Supporters sent flowers, telegrams and letters.

"Your speech was a wonder," wrote his eldest daughter, Margaret. "Every word was clear and easily heard. There were no statics to mar it."

A crowd of 20,000 supporters gathered outside his home, filling S St. and packing the area between Massachusetts and Connecticut Avenues. Many were women -- mothers mourning the loss of their sons in the war.

Despite Wilson's physical discomfort, he insisted on dressing in his morning coat and silk hat, and walked to his front door at about 2:30 p.m. to address the crowd. He spoke for two minutes, breaking down with emotion three times as the enthusiasm of supporters brought him to tears.

"I am not one of those that have the least anxiety about the triumph of the principles I have stood for," Wilson told them to sustained applause.

Enholm, standing in the hall of the Wilson House, recounted the scene that day: Wilson, a biographer of George Washington and scholar of government and leadership, fighting back disappointment in the results he had achieved but hoping for a different future.

"Wilson understood that even though he as an advocate had failed, that his idea would live on," Enholm said. "I think he took a lot of comfort in that."

The President died soon after, on February 3, 1924, at 67. He had presented the house to Edith as a gift, and she stayed there until own death 37 years later.

She lived long enough to see that two decades after her husband passed away, at the end of World War II, the United States played a critical role in forming the United Nations.