Calvin Ray’s castle is a beige ranch house that crouches outside the town of Wake Forest like someone trying to sneak in.

Rusted furniture and backhoes hulk on the front lawn. Beat-up trucks, one filled with dirty mattresses, brood in the backyard.

Once upon a time, Ray, who is 89, had big plans for a housing development in the neighborhood. Mimicking the grandly named McMansionvilles down the road, he would call it Lake Forest Estates.

But Ray’s dream dwindled down to five mobile homes, which he rents out. Locals call the streets that snake around his house “Calvin Ray’s Trailer Park” – and some take issue with his tenants.

On a scorching July day, one of those tenants, a man with a quick-to-boil temper and a troubled past, came to Ray’s house to complain about a busted air conditioner.

Jeffrey Daylon Mitchell died hot.

The events that led to his death are the subject of some disagreement – but the end result is not: Ray shot Mitchell in the chest with a .410 shotgun.

Police found Mitchell dead on Ray’s porch, blood pooled around his torso.

Ray says his tenant, who was 47, kicked in the door and threatened his life.

Mitchell’s family and friends say he was a loud, in-your-face kind of guy, but never would have harmed his landlord, whom he considered a friend.

The only opinion that really matters belongs to Ned Mangum, Wake County’s district attorney, and he sides with Ray. No charges have been filed in the killing.

“After reviewing all the evidence, we don’t see that a crime has taken place,” said Mangum.

The district attorney refused to discuss the evidence that led him to that decision. Instead, he referred a reporter to North Carolina’s instructions for jurors considering “defense of habitation” cases.

“Note well,” the first line reads, “the use of force, including deadly force, is justified when the defendant is acting to prevent a forcible entry into the defendant's home, other place of residence, workplace, or motor vehicle, or to terminate an intruder's unlawful entry.”

“Defense of habitation” has another, more common name: the Castle Doctrine.

A man’s home is his castle, runs an old English adage, and the legal principle that a man has the right to defend that home – with deadly force, if necessary -- is even older. The Hebrew Bible says that house-dwellers owe no “blood guilt” for killing intruders.

In the 18th century, William Blackstone, the English jurist who helped codify the common law system, said homeowners have a “natural right” to kill trespassers.

Twenty-seven American states have enshrined the Castle Doctrine in statutory law, sometimes with slightly different guidelines for when deadly force can be used. (In 17 more states, “stand your ground” measures extend self-defense protections to any place a person has a legal right to be, including the home.)

“It’s a reasonable presumption that if someone breaks into your home, you are in danger,” said Curtis T. Hill, a prosecutor in Elkhart, Indiana, and a member of the National District Attorneys Association’s executive committee.

Despite some controversy surrounding the Castle Doctrine, there are no reliable statistics on the number of such killings in the United States each year, Hill said.

It’s easy to see why: Calvin Ray’s killing of Jeffrey Mitchell doesn’t show up on public databases or on criminal records because he was never charged. Under North Carolina law, Ray also is exempt from civil litigation.

But the line between self-defense and aggression can sometimes be blurry, and in several recent cases prosecutors have rejected the Castle Doctrine defense.

In April, a Minnesota man was convicted of murdering two teenagers who broke into his house. Four months later, a Michigan man was convicted of killing a woman who knocked on his door, looking for help. In December, a Montana man will be tried for killing a German exchange student who broke into his garage.

In North Carolina, the debate between those who think Ray murdered Mitchell and those who think he acted in self-defense hinges on Ray’s front door.

It was nearly 95 degrees on July 12. The double-wide mobile home Mitchell rented from Ray offered little relief.

Mitchell and his 12-year-old son, Evan, walked 100 yards to Ray’s house to complain about their broken air conditioner, which the landlord had promised to fix.

Complaints about Ray’s properties – and his tenants – are common among his neighbors, some of whom live in neat modular homes.

In the past, a drunk driver, a sex offender and an ex-con who wore a devil tattoo on his arm and was accused of trying to rob a neighbor lived in properties owned by Ray, according to public records.

Heather Hartle, whose backyard abuts Ray’s, says she’s called Wake County police countless times, asking for help cleaning up the neighborhood and keeping it safe.

Ray patrols the streets himself in his Ford 150 pickup truck, Hartle said, but spends more time yelling at children than ousting troublesome tenants. As her young son biked down the street one day this summer, Hartle sharply warned him not to wander too far.

In parts of the trailer park, waist-high piles of crushed beer cans litter yards. Some mobile homes teeter on the edge of collapse.

Ray’s son, Andy Ray, said the neighborhood is “one that I would not care to be in.” He’s encouraged his father – futilely -- to get rid of the rental properties.

“He’s a very strong-willed person,” Andy Ray said. “If you’ve met him, you know that.”

I have, and I do.

Calvin Ray ended our brief interview this summer by running me off his lawn with his pickup truck.

“I done already answered that f***ing question,” Ray said as he gunned the motor and charged in my direction.

To be fair, Ray hadn’t wanted to talk in the first place.

Liver spots cover his red, raw skin. He had trouble hearing my questions. He said he wanted to put the shooting behind him.

“I liked him,” Ray said of Mitchell. “I hate that it happened.”

The two had known each other for nearly a decade. Ray said Mitchell was a good tenant. Hard-working. Paid his rent on time.

Ray drove Mitchell and his son to the grocery store and movies after Mitchell lost his license by racking up a string of DWIs.

Andy Ray says his father let Mitchell slide on his rent when those DWIs led to one of several stints in prison.

Ray and Mitchell occasionally argued, friends and family said, mostly about the condition of Mitchell’s rented house. A carpenter by trade, Mitchell expected home improvements to be done right, and Ray didn’t always deliver, they said.

Which brings us back to the broken air conditioner, and Ray’s front door.

All sides agree that the incident began on Friday, July 11, when Mitchell told Ray the AC wasn’t working. The landlord sent a repairman over to fix it.

When Mitchell came home on Saturday, it was on the fritz again.

Mitchell had spent much of Saturday with his son Evan, fishing in the pond near his house, his family said.

He had also been drinking heavily. His blood-alcohol content was 0.15, nearly twice North Carolina’s legal limit to drive, according to Mitchell’s autopsy report.

Three kinds of painkillers, including fentanyl, used in a potent patch given to cancer patients, were also found in his system, the report says.

Scott Mitchell, Jeffrey’s younger brother, said it’s possible the painkillers had been legally prescribed.

“He was 47, and he had worked in construction his whole life,” said Scott Mitchell. “That’s a hard job. His back was killing him.”

But doctors counsel against mixing painkillers, much less three different kinds, with large quantities of alcohol.

Family members said Mitchell had long struggled with liquor. Neighbors said they rarely saw him without a drink in hand.

“He drank a little too much,” said Mitchell’s ex-wife, Janice Mitchell Seanor. “But as he got older, he got better.”

More than anything, Mitchell’s family said, he loved his son Evan.

He had another son who recently turned 25, said Mitchell’s mother, Iva Spell. But father and son seldom spoke.

“Jeff had let (his elder son) down,” said Spell. “But Evan was his whole world. It was like he was getting a second chance to be a good daddy.”

Mitchell worked weekends to buy Evan fancy sneakers, watched from the sidelines at Evan’s baseball and basketball games. He had Evan’s name tattooed on his right shoulder, right above where he was shot.

If he had intended to hurt Ray, he would not have brought his son along on the night of July 12, Mitchell’s friends and family said.

But Spell said police told her that Mitchell had asked Evan to walk away from Ray's front porch. Wake County police declined to speak in detail with CNN about the shooting.

Ray said he was sitting on the couch, watching a weather report, when he heard Mitchell, who was 6-foot-1 and 178 pounds, hollering his name and banging on his front door.

He went back to his bedroom, Ray said, and retrieved his shotgun, which he had never fired before.

“I’ve never shot nobody, except a few Japs in the war,” said Ray, who served during World War II.

Ray said Mitchell kicked in his door and was met with birdshot from the .410, which tore through his ribs, right lung and heart.

Mitchell’s family members note that he was wearing flip-flops; they doubt that he could have kicked down the door.

Wake County police, in their application for a search warrant, say the door was halfway open when they arrived, with some of its molding lying on the ground. But it’s unclear when the molding fell. Many parts of Ray’s house seem to be falling apart.

After the shooting, Evan, who was a short distance away, ran back and knelt next to his dying father, according to family and witnesses.

The next day, Evan posted this picture of him and his father on Facebook:

His mother said Evan was once a carefree child – but not anymore.

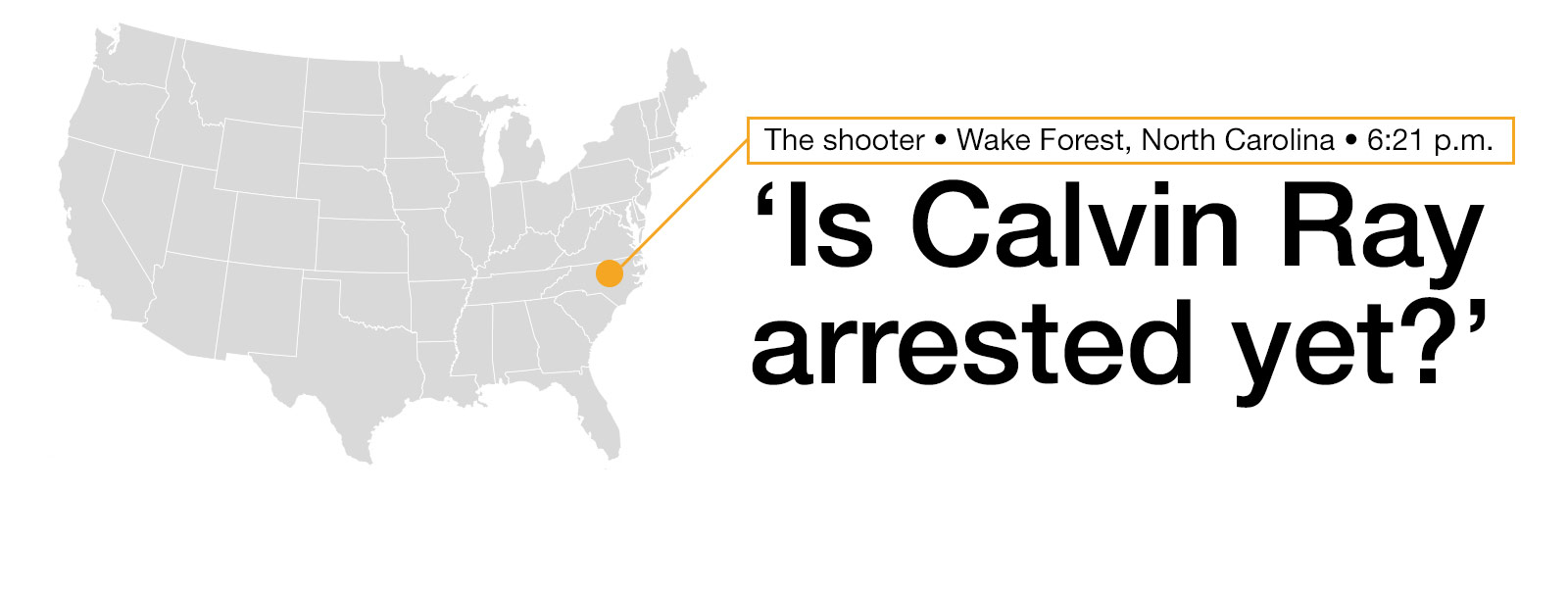

“He keeps asking me, ‘What’s going on, Mama?’” said Seanor. “Is Calvin Ray arrested yet?”

Guns Project

Guns Project