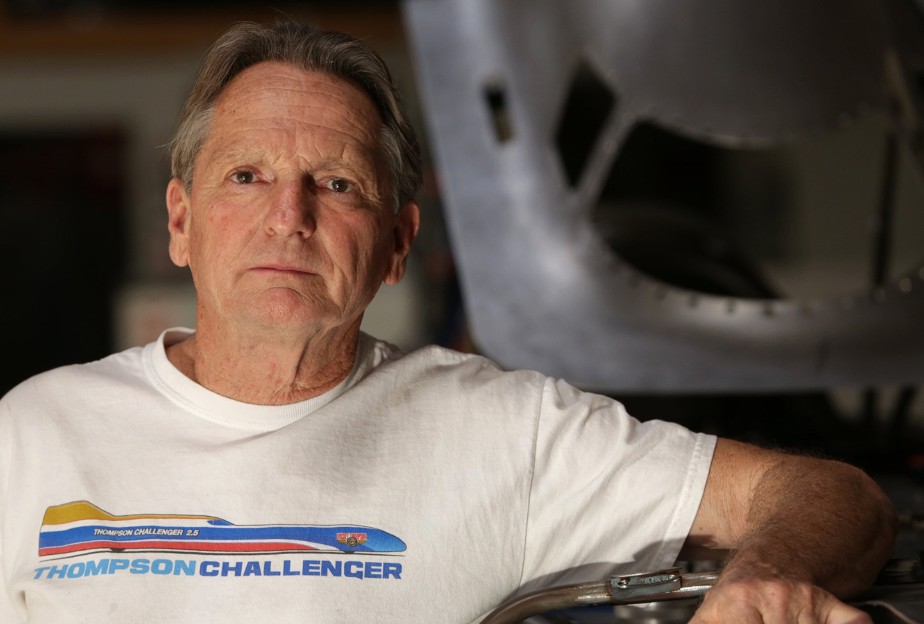

What drives Danny Thompson?

Why would a 64-year-old blast across the Utah desert faster than a 747 at takeoff? For Danny Thompson, it’s all about proving something to his famous father -- and himself.

By Ann O'Neill, CNN

Video and photographs by Brandon Ancil, CNN

Huntington Beach, California (CNN)

On the first day he started up his race car, Danny Thompson drank poison. He joked that he did it to impress a girl, but it was really an accident. A crew member had filled a Pellegrino water bottle with methanol, the sweet toxic fuel Thompson uses to warm up the engines.

It was hot, and the afternoon sun was beating down on the parking lot behind Thompson's garage. He wiped beads of sweat from his brow, took a long swig, and the next thing anybody knew, he was gagging and heaving in the bushes.

Man, did it burn going down. Burned coming back up, too.

He spent the evening in the emergency room, where a doctor hooked him up to an IV saline solution and flushed him out in more ways than one. The damage: $1,300.

"They freaked out at poison control when I called," Thompson said, his voice a hoarse growl. "That stuff can make you go blind."

But Thompson was unfazed. He was back at work promptly at 7 the next morning. He snapped on his helmet, climbed into the cramped cockpit and gunned 4,000 horses of methanol-fueled engines, this time mixing in a little nitro.

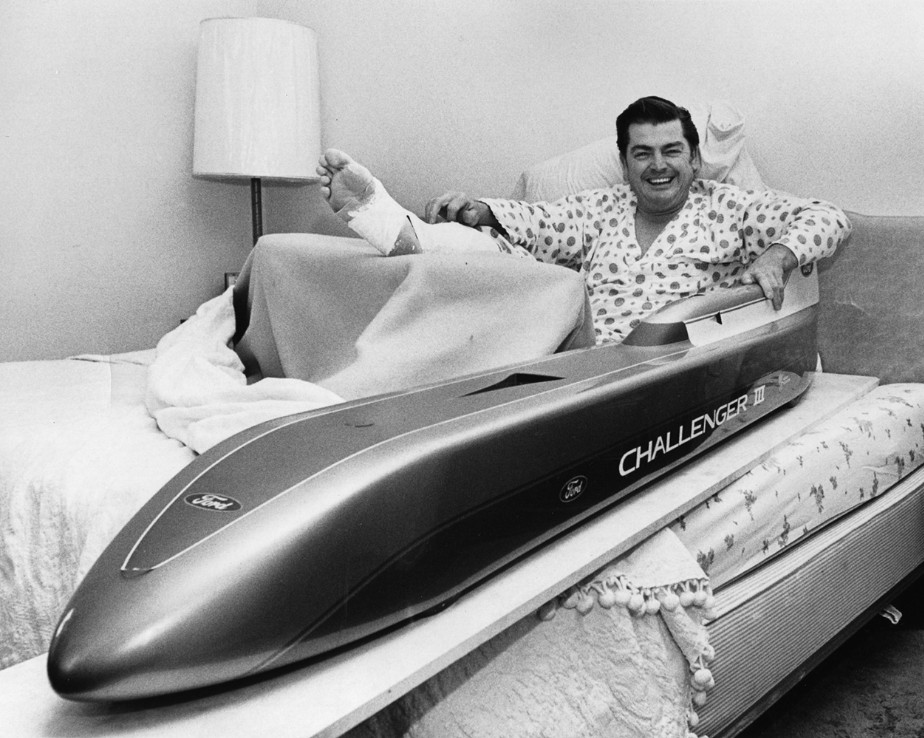

"Hoo-ya," he hooted, pumping his fist in the air. His baby, Challenger 2, was ready to roll.

Now, all he had to do was put on the wheels.

Danny Thompson is trying to become the fastest driver of a piston-engine car, just like his dad, Mickey Thompson.

Later this summer, when the temperature dances around the century mark and the horizon shimmers over the Utah desert, Danny Thompson will squeeze into the "cigar on four wheels" that he has rebuilt by hand and rage across the desert floor faster than a 747 at takeoff.

He has more than one chance to break the record. The first was to have come this weekend, but rains forced the cancellation of the 100th annual Speed Week at the Bonneville Salt Flats. The next will be in mid-September at Mike Cook's Bonneville Shootout, followed by the Southern California Timing Association's World Finals at Bonneville a few weeks later.

When his time comes, he will lie almost flat, his body mere inches from the earth, in a space the size of a coffin. He will see blinding white light ahead, noxious fumes will tease his nostrils, and he will hold onto the steering wheel for dear life; a wobble would signal that he's losing his grip on the salt.

If he's lucky, he'll see the mile markers zip by -- 2, 3, 4, 5 -- and then he'll pop the parachute.

Seventy seconds, that's all it will take. Spectators who cluster at the three-mile mark -- they can't get any closer to the finish line for safety reasons -- will spot a tiny dot and a rooster tail of salt in the distance. Then, because light travels faster than sound, a few seconds later they'll hear what sounds like a hive of angry bees.

In his mind, there can be just one outcome: Danny Thompson will hold the land speed record -- driving faster than 439 mph, maybe 450, maybe even 500 to hold onto the record for good. He'll be the master of a tiny universe, one of just a dozen men to top 400 mph in a piston-engine car.

Or, he'll die trying.

He is not even thinking about the third possibility: Failure.

His father, Mickey, was one of racing's early giants, an innovator who tasted both success and failure. He became the first American to top 400 mph, back in 1960, but a technicality kept him out of the record books.

Mickey was 32 then. Danny will be twice that age, and he doubts more than a few people will notice his feat, no matter how fast he goes.

Danny first seriously thought about restoring his father's race car, Challenger 2, four years ago, on the 50th anniversary of Mickey's record-breaking run. It had been on his mind for a while, and he wasn't getting any younger.

That was about $2 million ago. His retirement savings are gone, the 401(k) shot all to hell. He's flat broke, not sure where his next dime will come from. He doesn't have enough change to put gas in his pickup and jokes ruefully that he'll go home one night and find his wife of 26 years has finally given up on him and changed the locks. He prays for a sponsor to magically appear.

But the truth is he's never been happier. He can't wait to get up in the morning and go to work. He's fit, his cholesterol is low, and there's a twinkle in his eye. No 64-year-old should feel this frisky.

Danny knows he's risking his life. Mickey didn't want him to race because losing his son in a crash was his worst fear. In the end, it was Mickey who died too young -- and it wasn't behind the wheel of a race car.

When he lost Mickey, for awhile Danny lost a version of himself. Now the youthful race car driver in him is back, and he craves speed.

"He's hungry in a way that a very small percentage of people are," says Danny's 26-year-old son, Travis. "He's hungry in a way that is not vicious, that doesn't want to hurt other people. He's hungry for his own success."

It's not easy to measure that success. There's no pot of gold at the end of this rainbow, and likely no fame, either. So why is he doing it?

What drives Danny Thompson?

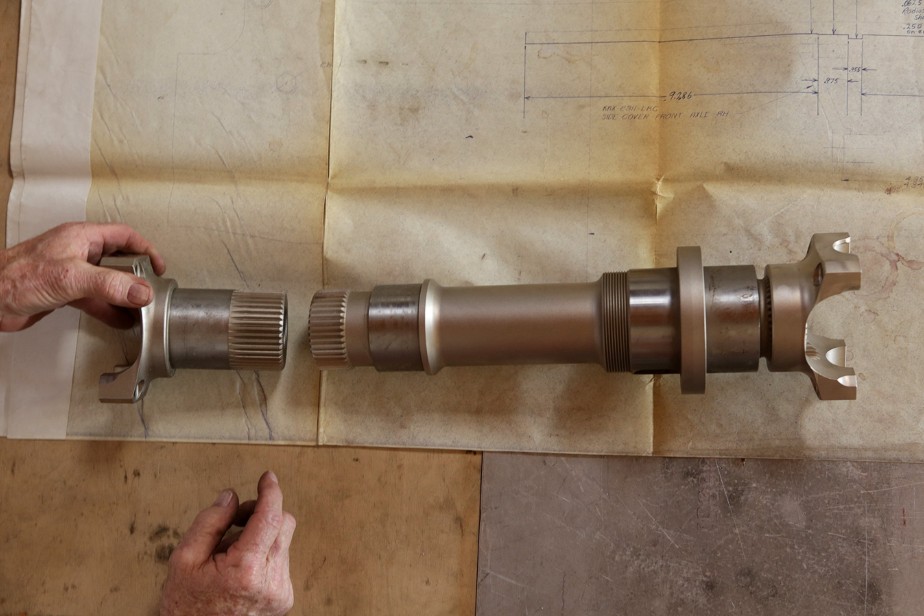

Racing legend Mickey Thompson built his cars from blueprints laid out on the floor of his garage in Southern California.

'Stand on the gas'

Racing is in Danny Thompson's blood. He idolized his hot-rodder father, an icon of Southern California's car culture whose motto was "stand on the gas."

Danny's parents met in high school, during spring break in Newport Beach; Judy, a cool blonde, beat Mickey at street-racing and he asked her to a dance. She didn't like the red-haired Irishman at first; he was short and a bit of a loudmouth. But he took her to a drag race at El Mirage, and love bloomed.

Judy was in the middle of a valve job, covered with grease, when she went into labor with Danny. Mickey wasn't home. He was off racing, and setting the first of many records.

As he grew up, all Danny wanted to do was race cars. By the time he was 9, he was entering events in the quarter-midget class at Lions, a drag strip his father managed outside Long Beach. Kids drove race cars a quarter the size of adult cars around a track Mickey built behind the grandstand.

When Danny won his first heat, he was pumped with pride and hoped Mickey would be, too. But that's not the reaction he got. Mickey sprinted from the other side of the track, leaping over the bales of hay lining the course. He yanked Danny out of the car.

"That's the last time you'll race, ever," he told his son.

Then he sold the car on the spot.

Someone had given Mickey bad information, told him Danny had flipped the car and was hurt. Mickey's reaction was purely visceral. He knew one thing: He didn't want his boy to die in a race car.

Mickey had lost eight friends racing and was haunted by two tragedies from early in his own career. He veered off course into the crowd at a sharp curve during the 321-mile mountain leg of the Mexican Road Race in 1953, killing five spectators. A decade later, Dave MacDonald, a rookie driver who was under contract with Thompson, slammed into the wall coming out of the fourth turn at the 1964 Indianapolis 500. He was incinerated in the crash, which also killed driver Eddie Sachs.

Mickey Thompson held more speed records than anyone else. He brought off-road racing out of the deserts and into the arenas of big cities across America. It made him a millionaire. But he never got over those deadly crashes, especially the one at Indy. He blamed himself, according to a sports editor friend from Long Beach.

Like most fathers, Mickey wanted more for his son: a better education, bigger opportunities, a step up from the working class. And so he did everything he could to thwart Danny's racing dream.

Danny grew up feeling trapped by his father's fears and perhaps by Mickey's competitive edge.

"He was just a gung-ho, 20 hours a day, flat out, out of my way or I'll run you over kind of guy," Danny said. "If we walked across the street, it was who's going to get to the other side first. You didn't walk to the door, you raced. And you pushed and shoved over who would be the one to turn the knob and open it. It was just the way it was."

Eventually Mickey's refusal to let Danny race came between them. Danny pleaded his case almost every day, but Mickey didn't budge. Danny rebelled. They fought about everything. As he put it, "We butted heads, severely."

Danny worked up the courage to challenge the old man after an argument about curfew. Mickey had taught him to box, but at 18, Danny was as tall as his dad, and he'd been working out. He thought he was hot stuff. He was ready to settle things with his fists.

They put on the boxing gloves, and Danny took a swing. His first punch caught Mickey in the jaw. He knew right away that he'd made a big mistake.

Mickey knocked him down with one punch, broke his nose. A few more jabs broke a couple of ribs. Each time he got back up, crying, Mickey would knock him back down.

"Don't get up, kid," Mickey begged. But Danny kept getting up, kept swinging, kept missing.

He was spent, used up. "At the end of the night I was, 'OK, I'll be home at 11 tomorrow night, Dad.'"

Danny Thompson's Challenger 2 is just 32 feet long, 34 inches wide and 26 inches tall, but it's built for speed.

A few weeks later, when he decided to pursue his dream and race motorcycles, Danny kept the gloves off and his mouth shut. He quietly moved out of the house, up to Mammoth Lakes. Mickey would call and ask how he was doing, and he'd just say he was working hard.

He won his first 18 races. Mickey eventually found out about the racing from someone else and showed up unannounced at an event in Mammoth. Danny couldn't tell whether his father was angry or proud. He won the first race, and then, distracted, crashed in the second.

After that, Mickey begrudgingly accepted that he couldn't stop his son. But Danny's career never really took off. He sensed that his father was working against him, behind the scenes.

His mother, who was by then divorced from Mickey, later confirmed his suspicions.

"They were on the outs for a long time because Mickey wouldn't let him race," said Judy Thompson Creach. "I often wonder how far Danny would have gotten if he had support."

He might not have become an Unser or an Andretti, but Danny Thompson eventually was able to make a decent living at racing. He won a few championships in Formula A cars, a class or two down from the prestigious Formula One circuit. He raced off-road cars, drove for Ford and worked on other people's cars at the Indy 500 and in Europe. And he worked for his father's entertainment business, which staged racing events in arenas around the country.

By the end of 1987, Danny said, his father was starting to come around to the idea of seeing his son behind the wheel of a race car. Mickey came to Danny with an offer he couldn't refuse: Let's take the Challenger to Bonneville, Utah, and go for that land speed record.

He asked Danny to drive.

Mickey went 406.6 mph at Bonneville in 1960, but because Challenger 1 broke down on the return lap, he never made it into the official record books. At Bonneville, a driver has to go out and back within an hour and average the speed of both trips. Otherwise, it doesn't count.

Today, racers drive jet-powered cars much faster -- the current land speed record stands at 763 mph -- and jets are where the glory is. But purists still see the beauty in doing it the old-fashioned way, with a piston engine. "The same way you drive to work," as Danny puts it.

Challenger 1 was put in a museum in Pomona, California, after Mickey broke 400. Eight years later, he was ready to go for the official record in a second Challenger. But the rains came early to Bonneville that year, turning the salt flats into a lake. The following year, 1969, the sponsors pulled out and put their money behind jet-powered cars. After coming close to 400 mph in test runs, Challenger 2 would spend the next two decades in storage.

1988 was going to be the Thompsons' year.

It was the end of a huge impasse between father and son.

"I get goose bumps when I talk about it because that was a real coming together," said Danny. It was the moment he'd waited for since he was 9.

'The Feud'

By the late 1980s, Mickey also was looking for a partner to help him run his entertainment business. His companies made high-performance parts and racing tires, and the Mickey Thompson Entertainment Group had made him a wealthy man. He was ready to start enjoying life a little more.

He found a partner in Michael Frank Goodwin, a charismatic former rock promoter who'd put on tours for Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, the Doors and the Rolling Stones. He'd popularized Motocross, arena spectator exhibitions at which drivers race motorcycles over obstacle courses.

But no partnership can survive two alpha dogs, and the merger was doomed from the start. Mickey accused Goodwin of failing to hold up his end of the deal. So began a four-year court battle that became known in racing circles as "The Feud."

Mickey prevailed in court. But he was never one to just beat an opponent; he had to crush him. He was relentless in his efforts to collect from Goodwin, who was equally determined not to pay Mickey a dime. When Mickey persuaded a judge to seize Goodwin's Mercedes, he drove the car to the courthouse the next day just to rub Goodwin's nose in it.

Goodwin appealed the case all the way to California's Supreme Court. He lost.

To avoid paying, Goodwin filed for bankruptcy and put everything in his wife's name. He sold his house in Laguna Beach and sailed off in a 57-foot boat named "Believe."

Mickey started telling people he was getting death threats. If anything happened to him or his second wife, Trudy, Mickey would say, Mike Goodwin was behind it.

Judy Thompson Creach, 84, raced Mickey Thompson on the day they met -- and won. She was working on a car when she went into labor with Danny.

'There's no closure'

Danny was on his way to work early on March 16, 1988, when he heard the news on his car radio. The details were sketchy, something about a tragedy involving "a major sports figure in Bradbury." He knew Mickey was the only sports figure who lived in the small, affluent community nestled in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains.

He turned north on the freeway, his heart in his throat. At the gate to Mickey's driveway, he encountered a line of police cars, lights flashing.

A young cop blocked his way: "You can't come up here, this is closed."

Danny identified himself as Mickey's son. He looked into the cop's eyes. He knew it was bad news, the worst.

The cop buzzed Danny through the gate. He raced up the hill and spotted two bodies on the driveway.

"There my dad was, covered up in a sheet," he said. "I just wanted to go over there and pick the sheet up because I couldn't believe it's him."

It was just a few weeks after Mickey and Danny had agreed to take the Challenger back to Bonneville.

Mickey and his wife had been gunned down, execution-style. Neighbors heard Mickey shout, "Don't hurt my baby!" and Trudy scream, "Don't shoot!" But they didn't hear any gunshots.

Police reconstructed the crime from neighbors' accounts and evidence at the scene. They say the gunmen wore hoods and used a silencer. They shot Mickey first to disable him, forced him to watch Trudy die, then finished him off with a shot to the head. They pedaled away on bicycles and were never found.

Sportswriter Jim Murray eulogized Mickey Thompson in his column as someone who "went through life like a guy escaping a bank robbery." More than 1,000 people attended the Speed King's service, some waving tiny checkered flags.

Speed came at a price. Mickey broke his back four times and too many bones to count. But racing merely broke Mickey; it was business that killed him, said Danny's mother, Judy. He shouldn't have gone out that way.

"I always said I'd give my life if Mickey had died in a race car. It would have been so fulfilling and so wonderful," she said. "That's what carries me through with Danny, and I think that's what carries Danny through."

"Absolutely," Danny said. "If you die doing something you love, then it's OK."

From day one, Goodwin wasn't talking to the cops. It took nearly 19 years for authorities to build and prove the case against him. Murder charges were filed in June 2004; Goodwin was convicted in January 2007.

To this day, Goodwin maintains he is innocent, the target of a vast, corrupt conspiracy. No physical evidence placed him at the shooting scene or tied him to the mystery gunmen. The key evidence against him was the feud, Mickey's reports of threats, the memory of a 14-year-old eyewitness and a second witness who came forward many years later to report he'd seen a man fitting Goodwin's description a few blocks away on the day of the murders.

Because the evidence against Goodwin was circumstantial, some people still doubt his guilt.

Danny Thompson is not one of them.

"It was a sad deal," he said about his father's murder and the long journey to the trial. By the time the verdict came, Danny had retired from racing, thrown everything into storage and moved to Colorado.

"People say, 'Ah, well, you have closure now that Goodwin's in jail.' You don't have any of that. There is no closure. Closure is my dad standing here."

Danny Thompson talked about life, death and unfinished business while shopping for bolts, screws and other car parts with CNN in tow in June.

Making good with Mickey

So what drives Danny Thompson? Ask him, and you'll get a smile and some talk about getting to go really, really fast.

But there's much more to it.

His father's murder knocked him down flat. He had grown up in the shadow of a larger-than-life personality, been denied his dream and finally gotten the validation he'd been waiting for, only to have his dream of a father-son racing team snatched away.

For years, he bottled everything up inside.

"I didn't do anything for a long time," he said. "My dad's been gone 26 years. I didn't feel right doing it without him."

The same year he lost his father, he gained a son. And so he focused on raising his own boy. He says he tried to be there for his son, Travis, and to let him make his own decisions. When Travis decided he wanted to finish high school in England and Scotland, Danny didn't stand in his way.

Travis works for Apple, and he is wise beyond his 26 years. He has no interest in racing cars, but he understands his father in a way Danny could never get Mickey. He can see why his dad would put everything on the line to beat an archaic record that will pay him no money and that hardly anyone will talk about.

"There's no specific reward at the end," Travis said. "You're the first person to do something. You've overcome incredible obstacles to do it. It's about the hardest, most esoteric kind of racing you can do. It probably doesn't get the recognition it deserves, but it's a bunch of guys alone in a desert going unfathomably quick. You have to be a little strange to do it."

Danny has been lured out of retirement a couple of times to race at Bonneville. Once, he raced one of his father's old cars. Another time, he set a land speed record in a Mustang.

As a boy, he'd been left behind with his grandparents when Mickey raced at the flats. Now, at a time when most men his age are thinking about slowing down, Danny Thompson craves the speed of the salt in the summertime.

The flats occupy about 30,000 acres in western Utah, stretching from the Great Salt Lake nearly to the Nevada border. They're the remnants of a salt lake that dried up during the Pleistocene Era.

The first speed record was set there 100 years ago by Teddy Tetzlaff in a vehicle called a Blitzen Benz. Racing on the salt flats became popular in the 1930s and since then several events during the summer and early fall draw thousands of drivers of hot rods, streamliners and motorcycles to the flats, which are on federal land and operated by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management.

Racers like the slick, flat surface, although traction can be a challenge. Courses at Bonneville run from five to seven miles, and most of the records are set between the fourth and fifth mile.

Drivers fondly refer to the flats as the Great White Dyno, a play on dynamometer, a device used to measure engine power.

"The salt, as soon as you drive out there, the place is just magic," Danny said. "The salt has its own story. You get out there before the sun even comes up and point towards Floating Mountain. It's all white and magic and you can see the curvature of the Earth."

The Great White Dyno and the 50th anniversary of Mickey's claim to fame got Danny thinking about their unfinished business. He's ready to stake his own claim this summer, which happens to be the centennial year for racing at Bonneville.

"I'll be 65 soon, and I've still got the passion to drive," he said. "There's not many things you can still go and do as a race car driver, and Bonneville is one of them. I can finish this up. I want to be the baddest man there."

Right now, George Poteet is the baddest man, at least in Danny's class. Poteet set the current land speed record for a piston-engine car -- 439 mph -- during last year's Speed Week. It's a tough needle to move if you consider that Mickey Thompson went just 33 mph slower half a century ago.

To clinch the record for the Thompson family name, Danny thinks he'll have to top 450 mph. He'd like to hit 500 mph, and he thinks Challenger 2 is up to the task.

A noxious cloud of methanol and nitro fills the air the first time Danny Thompson starts the engines of Challenger 2.

Indeed, during time trials earlier this month, he clocked 317 mph -- the fastest he's ever gone. Until then, all the work he had done was pure theory. Now he knows this car can perform.

The first Bonneville record he's going for, 392.5 mph for Challenger 2's vehicle class, is within sight. Then comes Poteet's world record.

But Poteet probably isn't Danny's biggest competition. It's the guy he says he's doing this for -- Mickey Thompson

"I think Danny's really driven over this because he never really grieved when his father died," said his mother. "He never really cried or showed any real emotion. He never really let go."

Judy is 85 now and a fixture at the garage in Huntington Beach. She was there the day the engines started. Wiping a tear, she called the rough growl "beautiful" and compared it to a symphony.

She has every intention of being at the salt flats to cheer Danny on and is confident he will break the record this summer.

"This is his way of making good with Mickey. He's doing this for himself, but he's also doing this for Mickey. All of these things he's kept inside himself, I think this is it. Danny will go fast."

Danny acknowledges that grief and that old competition with Mickey may play a hand in what motivates him. "People say I didn't grieve when my dad died. Did I show it? Probably not. Driving is my way of dealing with it.

"This is a quest my dad started. I want to eat that record. I want to bring that speed record to the Thompson family name. This journey is probably the most important because Bonneville is what put my dad on the map. I get to finish, and he didn't. Maybe there's always a little bit of that competitiveness."

And, he's making good with himself. Danny Thompson is finally getting to be the man he was meant to be. He's happy, funny and, as he put it, "64 going on 18."

Danny hopes his dad approves. "Hopefully he's up there watching and rooting me on. I miss the guy. I miss being pissed off at him, even."

This time the son is meeting the father on his own terms, as an equal.

CNN Longform

24 hours in the world's busiest airport

With 95.5 million passengers and 930,000 takeoffs and landings, Atlanta's airport is No. 1. CNN pulls back the curtain to expose a world unto itself -- and countless untold stories.

Taken: The coldest case ever solved

In five spellbinding chapters, CNN shows how cops cracked a case more than half a century old: the 1957 disappearance of 7-year-old Maria Ridulph. Was there justice for all?

War and fashion

War is ugly. Fashion is beautiful. There are photographers who shoot both: battlefields and runways, guns and glamour. At first, photographing war and fashion appear as incongruous acts that are difficult to reconcile. Until, perhaps, you take a deeper look.

Grit on wry: Dinner with Elmore Leonard

People who write about crime for a living have curious dinner conversations. As they pass the potatoes, they dwell on the unsavory details of hookers and pimps, junkies and bookies, crime scenes and corpses.