Getting there

It is a powerful need: to see the man who shaped your life from afar for almost 13 years. For 14-year-old Jesús and his mother, it was enough to propel them on a dangerous and illegal journey. They made it to America. But what happens next?

By Catherine E. Shoichet, CNN

Video and photographs by Evelio Contreras, CNN

Tucson, Arizona (CNN)

Jesús kneels next to a fleece Disney princess blanket on the bus station floor.

Toddlers squeal, announcements blare, and frantic passengers scramble to stock up on supplies for long rides ahead. The chaos doesn't rattle Jesús. The Guatemalan 14-year-old scans the room with a serene smile, flips through a book about dinosaurs and tickles a baby lying beside him.

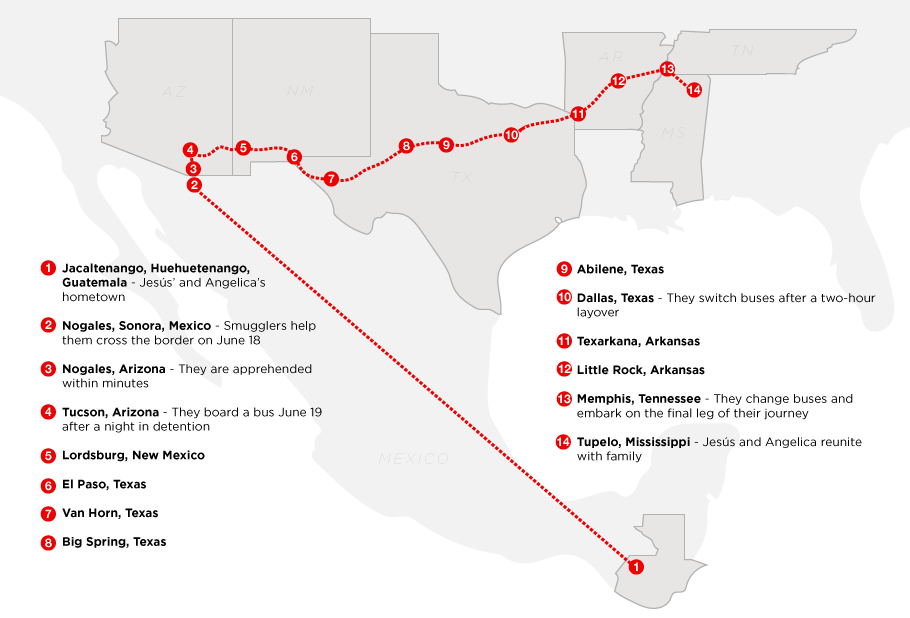

A week earlier, he and his mother boarded a bus bound for Mexico. Then, cloaked in predawn darkness, they climbed a ladder and scaled a 15-foot-high steel fence to cross into the United States. Border Patrol agents caught them within minutes. After one night in detention, they were released on this morning in late June and dropped off at the bus station here, more than 2,000 miles from their home.

Now that they've made it this far, Jesús has no doubt that the moment he's dreamed of his whole life is near. He is finally going to see someone he's long looked up to but never stood beside.

He's strung together details from nearly 13 years of phone calls, photos and video clips to paint a picture of the man he's about to meet:

He lives in Mississippi. He works in a Mexican restaurant as the head cook. He can slice a cucumber faster than anything Jesús has ever seen. His voice sounds kind when he calls Guatemala every day. His first question is always how Jesús and his siblings are doing.

He plays soccer in his free time. He roots for Barcelona. (So does Jesús.) He's good-looking but not very tall. He has short black hair. Some people say Jesús looks like him, but Jesús isn't sure.

There are many things Jesús knows but one he can't predict: What will happen when they see each other for the first time?

Three buses are about to take Jesús and his mother through 10 cities and six states on a winding 34-hour journey to Tupelo, Mississippi. The trip would make most kids squirm and shout, "are we there yet?" But Jesús is beaming.

"Voy a conocer a mi papa," he says.

I am going to meet my father.

Fourteen-year-old Jesús is excited about their journey while his mother, Angelica, is a bit wary. The unfamiliar scenery outside the window reminds her of how far they are from home.

A man with a booming voice pulls Jesús' mother aside. Before she leaves the station, he tells her, he wants to explain the documents she received from immigration officials this morning.

Angelica pulls out a stapled packet of papers and hands them over. The documents are in English, a language the 37-year-old can't speak or read.

The man is a retired Spanish radio host helping the wave of undocumented Central American immigrants who have arrived at the bus station in recent weeks. He slides his glasses forward on his nose and scans the first sheet.

"This says that you need to go to meet with immigration in Atlanta in one month," he says to her in Spanish. He points to words in bold that say, "Reason: Immigration Status Review." Then he turns the page.

"This says you were apprehended in Nogales," he says, pointing to a three-letter abbreviation circled on the form.

He stresses the importance of getting in touch with an immigration lawyer who can advise and guide her. He warns that she shouldn't skip the appointment with immigration officials.

"If you do not go," he says, "they can come for you to deport you."

Angelica has been released on parole and must check in regularly with immigration officials. She doesn't have a court date, but soon, it's likely she'll make her first appearance before a judge. Officials have said that dealing with the cases of women and children who recently crossed the border is a priority. But whether that means it will take weeks, months or years for Angelica's and Jesús' case to wind its way through the backlogged system is still anybody's guess. Only one thing is clear: the date scribbled on the form, beneath the word "PAROLED."

"You are protected until the 19th of September," he tells her. "If you do not appear, after the 19th of September, they can come for you."

"Any questions?" he asks.

So many questions swirl in Angelica's mind that she has a splitting headache.

Will she and Jesús make it to Mississippi? They've barely any money for the trip; what will they eat? Can they afford to pay for an immigration lawyer once they get there?

But those are questions she knows this man can't answer.

She shakes her head, folds up the paperwork and heads back into the waiting room.

Sebastian Quinac scribbles notes on a clipboard as Jesús, Angelica and other immigrants file into the waiting area.

"Don't worry," he tells them. "We will help you."

Today is Quinac's first day at this desert bus station. The Guatemalan consulate in Arizona has asked him to help keep track of the situation here.

New arrivals fill several rows of seats in the waiting area. As Quinac greets them, one mother lays her newborn down to change his diaper.

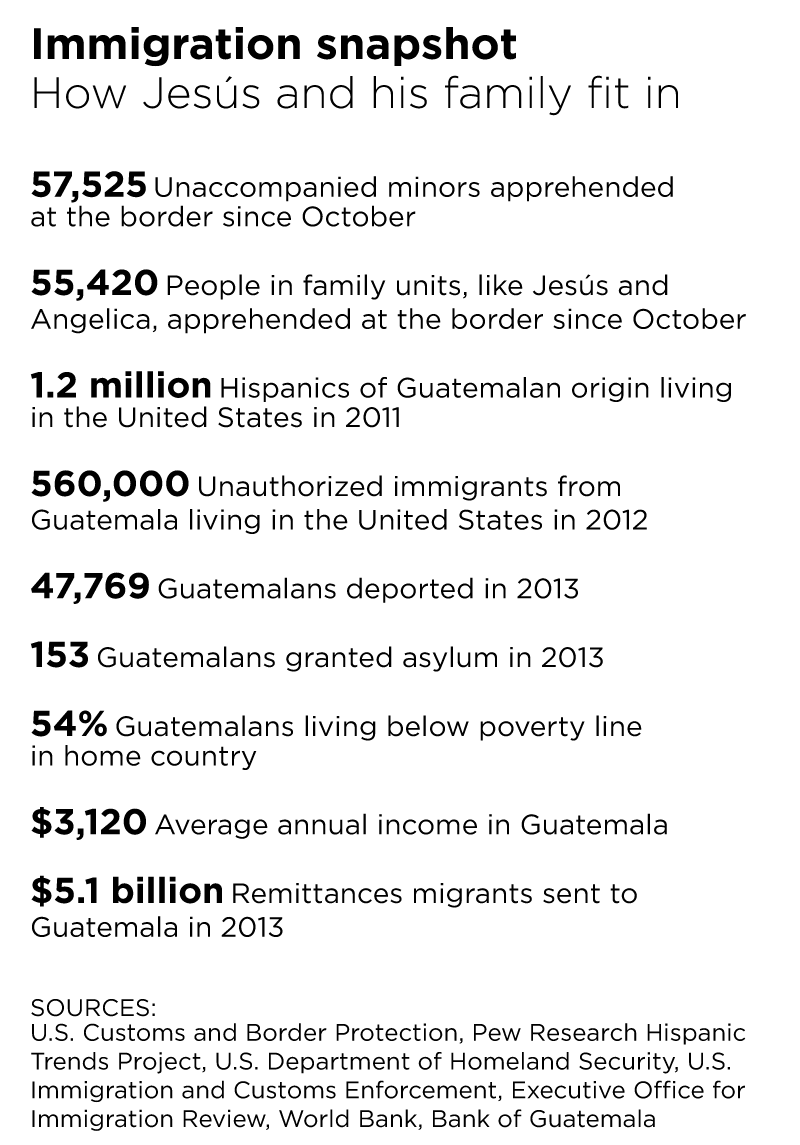

They're part of a surge of immigrants arriving in the United States daily from Central America -- mostly Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. Tens of thousands are children traveling alone, making headlines and fueling fierce debate in Washington and across the United States. There's also another growing group: mothers with children who cross the border illegally together.

It's a significant change in who's making the dangerous trek -- and who's getting caught. Illegal immigration from Central America has been on the rise for several years. But before, it was common to see Border Patrol agents capturing men and sending them to detention centers or quickly deporting them. Now, they're apprehending an increasing number of mothers and children, and the flow of people north shows no sign of slowing.

Since October, U.S. immigration authorities have taken into custody more than 55,400 people along the southwest U.S. border who were part of what they call "family units," adults with children crossing together. That's an increase of nearly 500% from the same time period last year.

The Obama administration has labeled the situation a "humanitarian crisis." The surge has shaken an already strained immigration system, overwhelmed officials and sent leaders scrambling to come up with new plans. The government response keeps changing as politicians face off over what to do.

On this day in June, there aren't enough detention beds to house families streaming across the border. So the mothers with children who've proved that they have family or friends who will house them have been released on parole. Dropped off at bus stations, they pick up tickets their loved ones bought them from afar.

These journeys beyond the border often go unseen.

In pockets across the country, in small towns and big cities, new immigrants slip into the shadows -- their lives far from the view of politicians who debate their fates and foreign to many Americans who, whether they know it or not, depend on their labor daily.

Angelica and Jesús agreed to let CNN follow them on the first leg of their journey inside America. They gave permission to be photographed, but asked CNN to identify them only by their middle names and not name the town where they're moving.

The road ahead could be complicated and dangerous for them as they learn to live in a foreign land where some will view their arrival with hostility. They don't know it, but they're on the way to a state where the governor calls fighting illegal immigration a top priority. Workplace raids, court battles and deportation orders could be part of their future.

They've managed to make it over the border fence, but they have no idea what's around the corner.

Even the next few days could be dicey. Quinac asks them where they're coming from and where they're going. He tells them to check in with the consulate again once they arrive at their destination. He wants to make sure they've made it safely after what's bound to be a long, confusing trip.

"I want you to trust me, because I am an immigrant, too," he says. "I have papers, thank God, to be here."

A brutal decades-long civil war made many -- including Quinac -- flee Guatemala in the 1980s and 1990s. Many said they were escaping repression and asked for asylum. When U.S. courts refused it, churches and activists stepped in, spawning a Sanctuary Movement that started in Tucson and expanded across the country. Eventually, a church-led federal court battle gave Guatemalans protection from deportation and forced the government to reconsider their asylum cases.

Since the war ended in 1996, thousands of migrants still have found reasons to leave Guatemala. In recent years, violence has been on the rise as powerful drug cartels expand their reach. And more than half of the country's population lives in poverty, according to the World Bank. The average person makes $3,120 a year.

That's one reason Angelica and her husband, Pedro, made a decision nearly 13 years ago that would change their family forever.

She was 18 and he was 22 when they married in their hometown of Jacaltenango, a city nestled among the Sierra Madre about two hours from the Mexico border. For six years, they scraped by on whatever Pedro could make as the caretaker of a coffee farm. They spent all the money he earned on the day he made it.

Their family grew to include two boys and a girl. They lived in a tiny adobe house that filled with mud when it rained.

Things were already tough. Then, men in ski masks ambushed Pedro one day at work, threatening to kill him if he didn't quit his job. At first, Pedro assumed they were empty threats aimed at shutting down a competing coffee farm. But then they found him again and made it clear they wouldn't take no for an answer.

Pedro and Angelica wanted to give their children a better life and send them to school. He'd thought about going to America before. After the threats, they agreed, there was no other choice.

On the day Pedro left, Jesús was 18 months old and so small he could barely walk without toppling over. His siblings were 3 and 5.

While they slept, Pedro gave them each a kiss and slipped out the door in the dark of night. Angelica cried. Pedro promised to return.

Along with a brother, he crossed the Mexico-U.S. border, trekked through the desert to Tucson and then headed east toward Mississippi, where more family awaited; Angelica's sister and brother-in-law had moved there after crossing the border illegally several years earlier.

It's a common story in Angelica's hometown. She says that nearly half her neighbors have family living in the United States and sending money home. Migrants abroad sent more than $5 billion to Guatemala last year, according to the country's national bank.

About 1.2 million Hispanics of Guatemalan origin live in the United States, according to 2011 Census figures. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security said there were about 560,000 unauthorized immigrants from Guatemala in the United States in 2012 -- the most recent estimate available.

Since the summer day when he left in 2001, Angelica says, Pedro's support has never wavered. He calls home three times a day and sends her and their three children everything they need. But still, she's felt alone -- left to deal with family problems, neighborhood disputes and the everyday drama of feuding children.

Angelica says Jesús is moody and often picks fights with his siblings. But today, he giggles and plays with the other kids waiting at the bus station. Outside, it's a scorching 100 degrees, but air conditioning keeps the place so cold that Jesús puts on a bulky Notre Dame sweatshirt and a pair of black winter gloves his mother found in the pile of goods collected by volunteers.

Angelica and the other mothers swap stories about how they crossed the border and their time in detention. They are all from Guatemala and on their way somewhere else.

A 22-year-old mom with a chubby 7-month-old is headed to Sarasota, Florida. A 30-year-old with two toddlers plans to end up in Memphis, Tennessee; a friend with a newborn is going with her.

Angelica and Jesús are the only ones traveling to Mississippi, but they'll all ride tonight's last bus out of Tucson.

Just before midnight, they board the bus bound for El Paso and settle into seats near the back. Angelica tugs on the blue V-neck shirt she's been wearing for days and runs her fingers through her long black hair. Jesús curls up on the seat beside her and rests his head on her shoulder.

They close their eyes and cuddle beneath a fuzzy blue blanket.

The journey from Guatemala has been difficult. And the road ahead could get complicated as Jesús and his mother learn to live in a foreign — and sometimes hostile — land.

As the sun rises, the bus barrels down Interstate 10 through the New Mexico desert. The sky turns bright orange, then yellow, then light blue, with gray mountains rising up in the distance. The driver speaks in the soothing voice of a seasoned captain, giving a play-by-play of the sights as they near El Paso.

"There's the Rio Grande on the right. Of course, everything on the right side of the fence is Mexico," he says. "We're driving right on top of the border line."

Two days ago, Angelica and Jesús crossed this line 340 miles away, near Nogales, Arizona. Angelica is still reeling from the experience. Smugglers, she says, tricked them.

In the dark of night, the men told her and Jesús to leave their things inside a house while they showed them where they'd cross the next day. So they left a backpack behind and headed with the men to the border.

Against a massive steel fence that seemed to stretch for miles, the smugglers leaned a large metal ladder with a rope dangling from the end. They barked out orders for Jesús to climb it -- and fast. His mother, they said, would follow.

Angelica protested, saying she needed their backpack to cross. Jesús, worried they'd hurt his mother, quickly fired back.

"No. First my mom. Then me."

They scrambled up the ladder and over the fence, slid down the rope and sprinted into the desert.

Their lime green backpack, which held clothes, mementos from home and 2,800 pesos (about $215), remained in Mexico with the smugglers.

Within 10 minutes, mother and son were in the hands of the Border Patrol. Angelica hadn't expected it to happen so quickly, but getting caught was always part of her plan.

She'd heard on the news in Guatemala, and from several people she knows, that U.S. authorities were apprehending women with children and then letting them go and giving them permission to stay. That's why she finally decided to travel to America, after years of weighing the rewards and risks.

Already, they've lost most of their possessions. Now, in bags they picked up at the Tucson bus station from volunteers, they carry immigration papers, donated food, clothes, and a blanket, and $16 they got in exchange for pesos. One bag says "Guidance when you need it most," and the other: "Team USA."

The bus slows to a stop under an awning that arches across the highway. Two men in dark green uniforms step on board.

The fence dividing the United States and Mexico is 30 miles south, but officials have set up a checkpoint here in Sierra Blanca, Texas, as part of efforts to crack down on drug trafficking and illegal immigration. The Hollywood Reporter dubbed it "the checkpoint of no return" in 2012; Willie Nelson, Snoop Dogg and Fiona Apple are among the celebrities who've gotten arrested here on marijuana possession charges.

Today, the Border Patrol agents walk slowly down the bus aisle, peeking in a few backpacks and asking each row of passengers a two-word question: "U.S. citizen?"

When Angelica, Jesús and the other Guatemalans respond with blank stares, one agent switches into Spanish and asks to see their papers. Angelica hands over the documents she got when she was released from detention.

He glances at the first page and then hands them back.

When the agents get off the bus, Jorgelina, a 22-year-old mother cradling her 7-month-old across the aisle from Angelica and Jesús, says she was shaken by the experience.

"It scared me," she says, "after everything we went through."

When they traveled on a bus through Mexico on the way to the U.S. border, she says, uniformed men regularly boarded and demanded money from passengers. Angelica nods in agreement but says this time she wasn't worried, even when the men asked to see her papers.

"We already have permission," she says.

Whether that's true has sparked a fiery debate in Washington, with critics arguing that lenient government policies are fueling the immigrant surge. Obama administration officials insist that they'll soon step up efforts to deport families who are illegally crossing the border -- and they stress that no one who does so has any kind of special permission to be in the country.

Still, Angelica says she's not concerned about getting kicked out of the United States. If she goes to her meetings and follows instructions, she thinks, officials will let her stay.

But something else does worry her as she watches out the bus window, scanning the desolate landscape dotted with small shrubs, a few cows and an occasional dilapidated farmhouse.

"There aren't places to walk," she says, "or children playing."

And where are all the cemeteries? "Don't people die here?" she asks.

The bus passes some cars for sale.

"Who will buy them if nobody is here?" Jesús asks.

As they continue their trip through Texas, Jesús tells his mom he has a theory.

"Maybe here the people are vampires, and they only come out at night."

Angelica felt that the time was right to risk coming to America. But the farther away she gets from home, the more doubt consumes her.

Angelica stares out the window at the city auditorium in Big Spring, Texas, where the bus makes a quick stop. The journey is nearly half over, and there are still no people to be seen, but the buildings have gotten grander. This one looks almost like a cathedral, with arches and big bricks.

Outside, there's an 8-foot-tall copper replica of the Statue of Liberty.

More than a century ago, the towering statue in New York's harbor became a beacon greeting millions of immigrants. A poem inside its pedestal said America's shores were ready to take in hungry, tired and poor, the "huddled masses yearning to breathe free." But there is no welcoming message inscribed beneath this small copy.

Top U.S. officials are sending a very different signal as Angelica and Jesús head toward Mississippi. At a White House news conference, spokesman Josh Earnest describes adults with children illegally crossing the border as a "growing problem." He says the government plans to build new detention facilities to hold them and boost staffing to process their cases more quickly.

In Guatemala City to discuss the issue with government leaders there, U.S. Vice President Joe Biden takes an even harsher tone.

"Those who are pondering risking their lives to reach the United States should be aware of what awaits them," he tells reporters. "It will not be open arms. It will not be 'come on.' It will be, 'we're going to hold hearings with our judges consistent with international law and American law, and we're going to send the vast majority of you back.' "

The top official in Mississippi, Gov. Phil Bryant, has pushed for more crackdowns on illegal immigration, joined a lawsuit over how the federal government handles deportations and wrote a report when he was the state's auditor detailing the millions of dollars he said illegal immigrants cost the state's taxpayers.

Angelica hasn't heard these politicians' messages. For now, all she knows is that everything out the bus window looks brown, dry and deserted.

She worries, is life here nothing but bleak?

When she heard about the opportunity to come to America, Angelica felt like she had to take it. The needs of her family keep growing, and there isn't enough money to go around. Her children want to stay in school. Her sister is trying to save her house from foreclosure.

She borrowed 28,000 quetzales ($3,600) to pay smugglers but felt that surely, with a job in America, she could make enough to pay the lender back.

Neighbors and cousins cried when she said goodbye. Angelica was risking everything but felt confident in her decision.

For her family, the years of separation had brought financial gain but also had serious costs. Jesús had started talking back and stopped listening to anything she told him. He needed his father's guidance, and she longed to see her husband again after so much time apart.

But now, she's beginning to have second thoughts.

There is one sacrifice that still weighs on her: She left two children behind in Guatemala.

She cries as she thinks about 16-year-old Arnoldo and 18-year-old Raymunda. Arnoldo was supposed to come with Angelica and Jesús but changed his mind.

"I am not going anymore," he told his parents, "because then my sister will be left alone."

Raymunda is studying to become a teacher. She has three more years of school to complete. Angelica never studied past elementary school. Some friends say she's wasting money by putting her kids in school instead of making them work. But Angelica never had any doubt that she wanted them to study more than she and Pedro ever could. She beams with pride as she describes the awards they've won as top students in their classes. It's an inheritance for them, she says, that nobody can take away.

As she looks out the window now, questions haunt her: Are Arnoldo and Raymunda ready to be on their own? Will her mother-in-law know how to take care of them while she's gone? Who will scrub the stains out of their school uniforms? Will anyone make her son the chicken soup and spaghetti he loves? Was leaving them behind a terrible mistake?

The hunger pangs won't stop. Jesús has barely eaten since they left Tucson, and Angelica is worried. When they change buses in Dallas, she picks out snacks she knows he'll like from the bus station store: a liter bottle of Coke and small bags of Cheetos and Ruffles.

After midnight, they get on the bus again.

They wake up hours later in Memphis. On their layover there, they brush their teeth in the bathroom and stare across the waiting area at a wall displaying a map of the United States.

They smile as at last they board another bus for the final leg of their journey. They are on their way to Mississippi.

Jesús looks out the window and leans in towards his mom. They speak softly to each other in Popti', an indigenous Mayan language used in their hometown, and in Spanish, the national language of Guatemala.

"I beat my brother and sister because I am going to see my papa before them," he laughs.

As he waits, he stretches out his arm and reaches up, tapping his fingers on the window.

For years, his father has sent him money for school and soccer uniforms, toys and video games. But Jesús felt sad when he'd see his cousins walking with their fathers.

"A toy isn't the same as a father's affection," he says.

He presses his face against the window, his mouth agape as he stares at the new world he hopes to call home.

The bus pulls into a Tupelo gas station parking lot that doubles as a bus stop. Jesús and Angelica peer out the window for signs of someone they know and then step outside, looking lost.

As the sticky Mississippi heat hits them, a man walks around the back of the bus. He is carrying a dozen red roses.

His eyes meet Angelica's. Tears stream down his face. It's like a part of him that was missing is returning to his body. Suddenly, everything fits.

"I love you," Pedro tells his wife. He leans in, presses his face into her shoulder and squeezes her tight as they both sob. She wraps her arms around him.

He looks different than Angelica remembers. The last time she saw him, he was 28. Now, he's 41. He's not as thin, he has less hair, and some of it is gray. But her feelings for him haven't changed. After years of being alone and days of uncertainty about whether they'd make it, she finally feels safe. She wipes tears from her eyes.

Jesús runs up from behind her and throws his arms around his father's neck.

"Thank you for coming to see your papa," Pedro says.

He hasn't slept or eaten for days. Waiting for Angelica and Jesús to arrive, he tortured himself. Would they make it across the border? Would they get lost in the desert? If authorities caught them, would they release them from detention or send them back to Guatemala? For so many years, he fought to make it in America so his family would not suffer. How could he have allowed them to make the dangerous trek north?

He cried in his bed at night, paralyzed with fear. His own illegal crossing in the desert 13 years ago nearly broke him. He remembers the heat and the hunger and the fear that he wouldn't make it -- and the skeletons he saw of immigrants who didn't.

Now, Pedro looks up at the sky and then down at his son. He blinks away tears of disbelief.

Jesús doesn't cry. He can't stop smiling.

Pedro drives a friend's car past a duplex and points out the window. "That's the place we could rent," he says.

Right now, Pedro lives with three others in a two-bedroom apartment. They all work in the same restaurant.

"We're here," Pedro says as he pulls off a quiet country road into his apartment building's parking lot.

It's a far cry from their six-room house in Guatemala, which has potted plants out front near a bustling street. Here, there's a bed in the living room, gray carpet on the floor and a tiny porcelain cross above the couch.

In Pedro's room are two twin beds. Normally, he shares the space with the restaurant's second cook, but his roommate went to stay with a sibling when he heard that Pedro's family was coming. Jesús will sleep in the cook's bed now.

Back home, Jesús has his own bedroom filled with school awards and posters on the wall of lucha libre wrestlers and soccer stars, like Argentina's Lionel Messi. Here, the only decoration Pedro has placed on the wood-paneled wall is a framed photo of his three children.

They pose with bicycles bought at Christmas with money their father sent from America. Jesus and his brother straddle sleek red bikes. His daughter shows off a pink one.

Growing up, Pedro says, his family never had enough money to buy him a bicycle. He pulls a photo album from under his bed.

"My family is my life," he says.

On one page, his older son receives an academic award. On another, his daughter wears her plaid school uniform and holds a gray laptop he sent her from America. Pictured together, his three children stand in a row, the tops of their heads like a staircase. His wife sits stoically on the front step of their house, which he sent the money to buy but has never seen in person.

"When I see them," he says, "it motivates me to work and get ahead."

When Pedro first came to America, he struggled to make ends meet. Some Guatemalans helped him find a road construction job in Mississippi, but that dried up after several months. He helped clean yards and then packed CDs at an Alabama warehouse until that fell through. For weeks, he couldn't find work.

A friend told him about a job at a Mexican restaurant in Mississippi, washing dishes for $270 per week. He stayed there for more than a decade, working his way up. Now, he's the head cook at another restaurant, where he went when the owners at his old job wouldn't promote him.

Once he paid off the $5,000 loan he'd taken out to cross the border, he began to send a few hundred dollars home every two weeks. Now, he sends about $1,000.

Often, he's slept with the family photo album under his pillow or in his arms after long days at work.

"Now, she is going to be my pillow," he says, smiling, as his wife walks by.

"I love her," he says. "I hope she still feels the same way about me."

Hanging on the wall is a black backpack containing Pedro's important documents, including paperwork he's filed to try to gain asylum in U.S. immigration court. Letters from a lawyer and a doctor Pedro once worked for in Jacaltenango say death threats forced him to flee Guatemala. A police report filed by Angelica details more recent threats made against their family. Men in the local market have cornered her, the document says, claiming that her husband will be killed if he ever returns to Guatemala. "She does not know the individuals and has no problem with anyone," it says, "so she is filing this report in case anything happens to her and her family."

Angelica thinks the recent threats might have something to do with a business deal her father made that hasn't panned out. Talking about it makes her cry.

Seeking asylum is the best chance Pedro has to stay in America. It's a claim Angelica will have to make as well if her case ends up in court.

But it's a hard sell. To get asylum, an applicant must prove that they've been persecuted or fear persecution based on race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion.

Last year, only 53% of asylum claims were granted nationwide. In some parts of the country, the approval rate is far lower.

In February, Pedro says, he could face deportation if a judge doesn't grant his request. Fears about what that would mean financially for his family haunt him. But his greatest worry has nothing to do with money.

For 13 years, he couldn't hand Angelica gifts at Christmas or give her a hug on Mother's Day. Now that they're together, he wants to give her more: clothes, makeup, a nicer place to live. He wants to make plans for a new life.

Now that she's finally made it to America, what if he gets sent away?

Hours after arriving in Mississippi, Angelica and Jesús shop to replace the clothing they lost when smugglers tricked them into leaving their backpack behind in Mexico.

"Mami!" Jesús screams.

Angelica bolts out of bed. Pedro follows her into the kitchen.

A pot of black beans left on the stove is boiling over, and the apartment smells like smoke. Pedro flips on the hood fan and turns down the burner.

In Guatemala, Angelica cooks with gas. Here, the burners are electric.

"I know how to cook, but in my house," she says. "This is someplace else."

Angelica didn't sleep well last night. The roar of passing trains and the spritz of a wall-mounted air freshener that sprays every 36 minutes kept waking her up.

Everything here is foreign. She struggles to understand the buttons on the microwave, the coins in the pocket of her jeans, how to turn on the washing machine downstairs.

There aren't enough dishes. The stove isn't clean.

But Angelica tries not to let it bother her.

"Little by little," she says, "we will learn."

In the kitchen, Jesús slowly chops up a cucumber to make himself a snack. He thinks about a video his father once sent, showing him speedily slicing and dicing a cucumber in the restaurant's kitchen.

And he thinks about his family in Guatemala. They're preparing food now, too, for a festival they celebrate each year. There will be tamales and marimbas, dancing and traditional music. One song sticks out in his mind. It's about migration -- and about missing Guatemala when you're working in the United States.

"When I am there, I want to go back home," the song says. "But when I am home, I want to go back there."

Jesús can't quite remember all the words, but he remembers the reason the singer feels torn between two countries: "because of the economic possibilities," Jesús says.

It's a reality he's beginning to understand in his first days in America. He hasn't had much of a chance to explore on his own. But the desolate landscape he saw from the bus window stuck with him. America must be a place, he says, where you're always trapped inside.

One of his father's friends describes it as a "cage of gold," where you constantly work to make money and never go out.

Jesús gazes across the way at kids' bicycles on a nearby balcony. In Guatemala, he had three bicycles: the tiny red one in the picture his father treasures, another that got destroyed when his grandfather accidentally ran over it and a black one he's been riding ever since. Here, even if he had a bike, he doesn't know anyone to ride with. The only toy in the apartment is a remote-controlled helicopter, and the propeller just broke.

It's been two days since they arrived in Mississippi, but Jesús has spent only a few hours with his father, who puts in 13-hour days at the restaurant and goes to sleep soon after he gets home at 10 p.m. To pass the time, Jesús has been searching YouTube for videos of Guatemala on his father's laptop and watching the few movies he can find.

He curls up on the gold-colored couch in the living room and flips through a DVD menu. He selects "Languages" but doesn't find what he's looking for there. The choices are French or English.

"Nothing in Spanish," he sighs, shrugging his shoulders and hitting play.

The 2010 "Karate Kid" remake starts up on the screen in English.

The movie's opening sequence shows a woman and her son getting ready to leave everything they know behind in the United States and start fresh in China. The boy looks dejected as he says goodbye to his friends and then struggles to speak Mandarin and fight off bullies in their new home.

His upbeat mom tries to put a positive spin on things.

"It's like we're brave pioneers on a quest to start a new life in a magical new land," she tells him.

In Guatemala, Jesús' grades were so good that he was one of 158 children nationwide selected to be a congressman for a day. He loved studying natural and social sciences. He spent his spare time playing video games and watching "Transformers" cartoons.

Here, he plans to spend the summer studying English so he'll be ready when he starts school. Right now, the words characters speak on the TV screen are just a sea of sounds washing over him. Only greetings like "hello" and "goodbye" stick out.

He's seen parts of the movie a few times in the past two days. It's one of the few DVDs in the apartment that aren't home movies from Guatemala. This time, he wants to watch it all the way through and find out whether the Karate Kid learns how to survive.

His mother is also in search of reassurance. A few hours later, a video of her daughter's three-day school field trip across Guatemala blares on the big-screen TV, filling the apartment with sounds of rushing waves and laughter.

As scenes flash by, the memories of those moments play in Angelica's mind.

Daredevil circus acts. An ancient cobblestone street. A boat packed with wide-eyed students gently drifting across a clear blue lake.

When her daughter appears on the screen, Angelica stands up and smiles. She recorded the video and mailed it to Mississippi so Pedro could feel like he was on the trip, too.

She never imagined she'd be on the other side of the border with him, staring at a TV screen to feel close to half of her family.

This is the moment Jesús has long awaited. For years, his father sent him money for school and soccer uniforms, toys and video games. But "a toy," Jesús says, "isn't the same as a father's affection."

Angelica and Pedro flip off the lights, kick off their shoes and lie down in the twin bed beneath the picture of their children.

So many nights, Pedro has laid here and dreamed of them. He never thought they would be by his side.

Already, he can't imagine living without his wife and youngest son. Maybe someday, he says, his other two children and his mother can come, too.

He hopes Angelica's and Jesús' release from detention is a sign that America's immigration policies are changing, that more families divided for years will have a chance to be together.

Just a few inches away, Jesús kneels on the floor and leans in toward a laptop on a bedside table. The glow of the screen shines like a spotlight on his wide eyes as he watches a movie about the Mayan Empire.

Jesús is excited for school to start and to go fishing with his father on his day off this week. He tells his mom that even if his parents get sent back to Guatemala, he plans to stay in the United States.

"I am going to work, like my father did. But first, I am going to study."

The family has just returned from a shopping trip to buy pots, pans and dishes they can take with them when they move into a new apartment. Pedro's two-hour afternoon break is almost over. He doesn't want to leave Angelica's side, but soon he must get out of bed and head back to the restaurant.

Hearing him talk about work makes Angelica anxious. She starts a new job cleaning tables at the restaurant tomorrow, and she's worried about messing up.

What will they ask her to do? Will she be any good? What if she doesn't understand something?

Pedro tells her not to worry. "Don't blush if they tell you you're doing something wrong," he says.

Angelica says she always turns red when she's under pressure.

"Be calm. Just ask questions," he tells her, "and if you're in between tasks, always ask what else needs to be done."

She knows he's right. It's been a while since she's held down a paying job. But for years she's been taking care of their kids, so she knows how to work.

In the dark, they speak to each other softly and gaze at the ceiling like young lovers searching for shapes in a cloud-streaked sky.

More on immigration

Stories from a desert bus station

At this crossroads of hope and fear, America's most recent undocumented immigrants carry tickets to their destinations – and papers stamped with the date they could be deported.

Daniel's journey: How children are creating a crisis

Immigration reform has stalled in Washington, but a shocking new reality has brought the issue back to the forefront. How did this happen?

Documented

He earned a college scholarship, paid taxes and even won a Pulitzer Prize – all as an undocumented immigrant living in America. Jose Antonio Vargas tells his story.

Your path

If you’ve immigrated to the United States, we want to hear your story. What was your journey beyond the border like? Share a personal essay about your experiences and upload a photo of yourself.