Besting Ruth, beating hate: How Hank Aaron made baseball history

Hank Aaron made sports history on April 8, 1974. On that day he broke Babe Ruth's total home run record -- something few thought could ever be done -- but swinging that bat came with a great personal risk. CNN takes a behind the scenes look at how this sports legend was made.

By Jen Christensen, CNN

Hank Aaron is met by his Braves teammates and his own mother who grab the slugger at home plate to celebrate his breaking baseball's total home run record on April 8, 1974, at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. (AP photo)

Editor's note: The following story contains epithets that may be offensive to some readers.

It was 40 years ago today that Henry Louis "Hank" Aaron did what most thought was impossible. On April 8, 1974, the Atlanta Brave hit home run number 715.

It broke Babe Ruth's all-time home run record. It was an incredible athletic accomplishment made even more incredible because it happened in the shadow of hate and death threats. Those threats came from people who did not want an African-American to claim such an important record.

Aaron finished his career with a record 755 homers, a stat so impressive it has been bested by only one player, Barry Bonds, who finished his career with 762 – though that record has come under a cloud of steroid-use allegations.

When Major League Baseball scouts first took a look at the teenage sensation in 1952, they saw potential but could not know the legend he'd become.

Those scouting reports show a player with natural talent but also little coaching or experience. He grew up in the 1930s and ‘40s deep in the heart of the segregated South – an African-American man without access to organized baseball teams, fields or equipment.

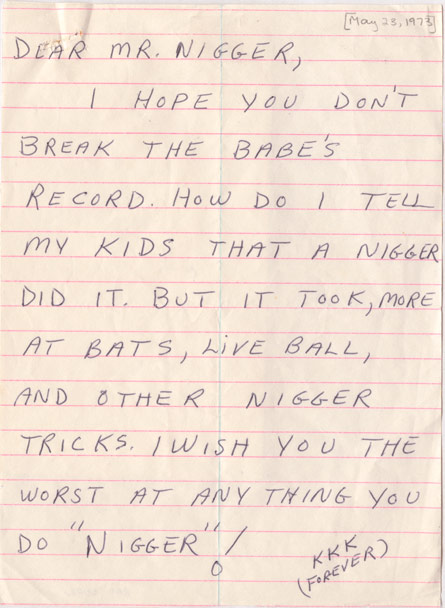

The nearly million letters sent to Aaron as he chased the home run record also show an ugly side of American culture in the early 1970s. The letters drip with hate and threaten his life just for playing baseball.

Some of those letters and other documents from Emory University's Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (MARBL) will be on display at Emory's Robert W. Woodruff Library in an exhibit that opens April 24 in Atlanta. The letters are a testament to what Aaron overcame to become one of the greatest players of the game.

The scouting reports

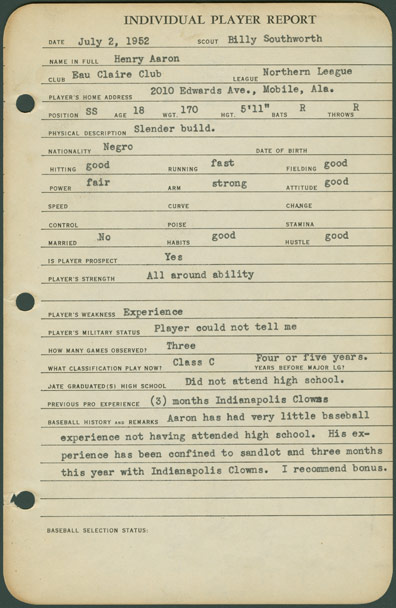

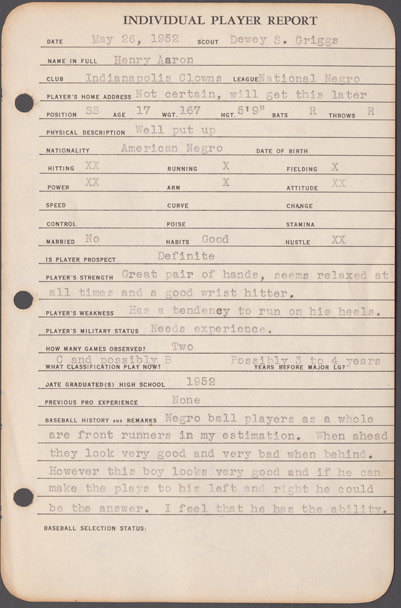

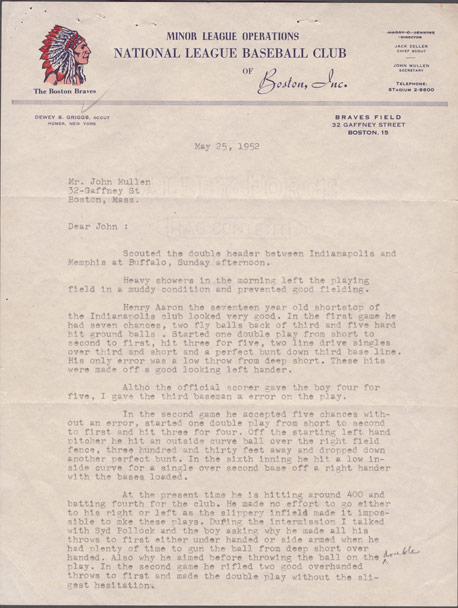

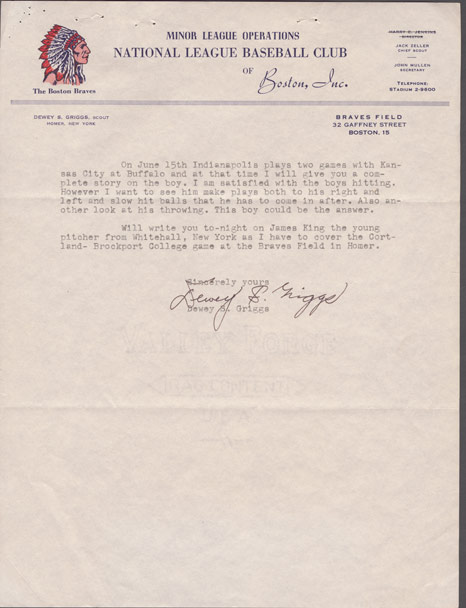

The May 26, 1952, report from Braves scout Dewey Griggs describes Aaron as physically "well put up." Another report from July from scout and baseball Hall of Famer Billy Southworth describes Aaron's "slender build."

Listed as 5'11", 170 pounds on one report, he was even skinnier when he lived in Mobile, Alabama. It was so noticeable that a Dodgers scout told Aaron he'd never play professionally.

Griggs and Southworth disagreed. Perhaps they knew skinniness could be fixed. It happens when a young man's diet is limited to what his family grew in their garden. After all, Aaron was only 18, and there was still time to fill out.

By all reports, Aaron's childhood was marked by his obsession with baseball. He even got kicked out of high school when he cut too many classes to listen to Dodgers games on the pool hall radio.

When Aaron's hero Jackie Robinson, the first African-American to integrate Major League Baseball, came to Mobile in 1948, Aaron cut class to hear the Dodger speak at a drugstore. Later that day, he told his father that's what he wanted to do with his life. Robinson "gave us our dreams," Aaron wrote in his autobiography.

There was no school team, so he'd play fast pitch softball at school and pickup baseball games with neighborhood kids. They carved a makeshift diamond in an abandoned lot, their baseball made from rags.

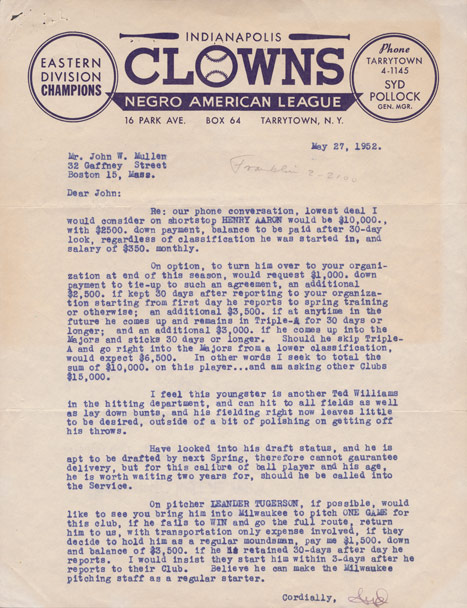

A letter from Syd Pollock, the owner of the Indianapolis Clowns to Braves executive John Mullen concerning the terms of Hank Aaron's contract. From the Richard A. Cecil Collection, Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, Emory University (MARBL).

He remembers though, even then, he had to separate his playing from the racial hate that swirled around him.

"When I was growing up in Mobile, Alabama on a little dirt street, I remember my mother about 6 or 7 o'clock in the afternoon. You could hardly see and I'd be trying to throw a baseball and she'd say 'Come here, come here!' And I'd say, 'For what?' She said, 'Get under the bed,' " Aaron said in a rare interview with CNN this month.

The family would hide under the bed for several minutes and then "the KKK would march by, burn a cross and go on about their business and then she (my mother) would say, 'You can come out now.' Can you imagine what this would do to the average person? Here I am, a little boy, not doing anything, just catching a baseball with a friend of mine and my mother telling me, 'Go under the bed.'"

In the scouting report, Southworth notes Aaron's strength is his "all around ability," but "his experience has been confined to sandlot and three months this year with the Indianapolis Clowns."

Nevertheless, Southworth closes his report with "I recommend bonus."

In the space for player's strength, Griggs writes, "I feel that he has the ability." And in the letter Griggs wrote to the Braves front office, he closes his letter about 18-year-old Aaron with, "This boy could be the answer."

When the Braves bought Aaron's contract from the Indianapolis Clowns in 1952, they promised him $350 a month and paid the Clowns $10,000. The Buffalo Criterion newspaper reported this was "one of the highest prices paid for an American League star in many years."

Aaron's signing bonus? A cardboard suitcase.

The ticket to his future

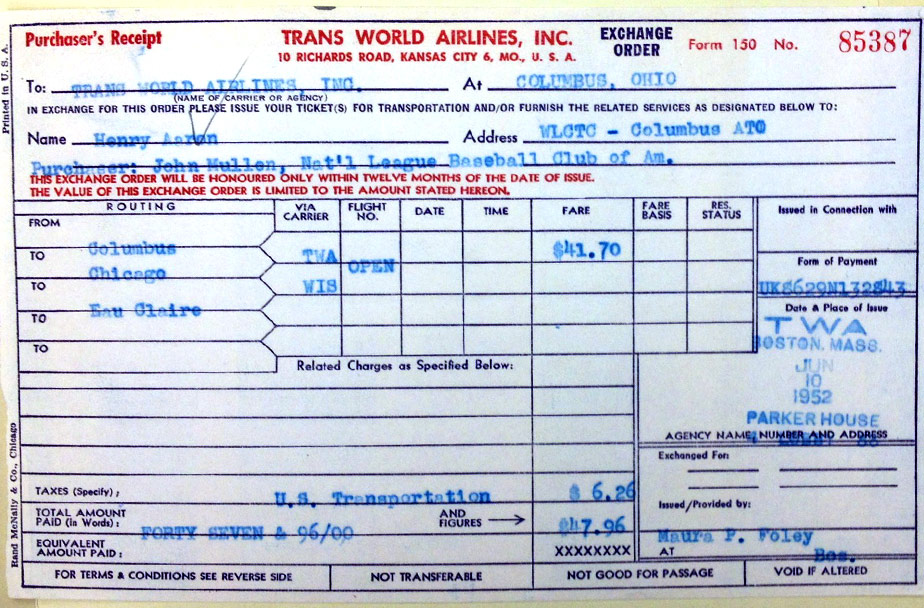

With his new gig, Aaron embarked on what would be his first airplane ride in June 1952 to meet the Braves Class C farm team in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. The ticket cost $47.96. He writes the flight terrified him: "I was a nervous wreck, bouncing around in the sky over a part of the country I'd hardly ever heard about, much less been to, headed for a white town to play ball with white boys."

The ticket for the flight the Braves booked to bring Hank Aaron to play for the Braves Class C farm team in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. From the Richard A. Cecil Collection, Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, Emory University (MARBL).

Eau Claire wasn't a "hateful place for a black person – nothing like the South – but "we didn't blend in," Aaron wrote in his autobiography. When he went out, people stared. Nonetheless, the Northern League named him Rookie of the Year. He batted .336.

Aaron's race became more of a challenge when the Braves promoted him to Class A ball the next season. He and Horace Garner and Felix Mantilla broke the color line in the Sally League, the Deep South's league. With the Class A team based in Jacksonville, Florida, Aaron writes the mayor warned him he'd hear racist shouts from fans that he should "suffer quietly."

Fans threw rocks. They wore mops on their heads to mock the black players. They threw black cats onto the field. The FBI investigated death threats. The players knew to ignore the hate, but "we couldn't help but feel the weight of what we were doing," Aaron wrote in his autobiography.

The stadiums had segregated seating. Brown v. Board ended "separate but equal" on paper in 1954 -- the year Aaron got promoted to the big league. But, like with other facilities, the "whites only" signs didn't come down immediately. It wasn't until 1961 that the Braves took down the "whites only" signs, according to Aaron. The segregation also extended to the team.

While the white Braves got to eat in restaurants in the South, the black players took their meals on the bus. They were also housed separately in towns that kept public accommodations segregated. Some Florida newspapers wouldn't even print the pictures of the black players. But by the end of his Sally League season, Aaron says in his autobiography "little by little -- one by one -- the fans accepted us. Not all of them, but enough to make a difference … and we were part of the reason why."

His hitting also got him noticed. In 1953, the South Atlantic League named him Most Valuable Player. He won the batting title with a .362 average and led the league in hits at 208 and 115 runs. He had more total votes than the next three vote-getters combined. He started his Major League career that following year.

Aaron had record success. He was named an MVP (1957), a Gold Glove (1958, '59, '60) and picked for countless All Star teams. Over the 23 years he played, Aaron achieved an incredible .305 lifetime batting average. Yet some fans couldn't see past their hate. That was never clearer than when he got close to breaking Babe Ruth's home run record.

Racist hate mail

The Braves front office kept a handful of the 990,000 letters Aaron received in the early 1970s. He received so many that the U.S. Post Office gave him a plaque for receiving more mail than any other American (not including politicians).

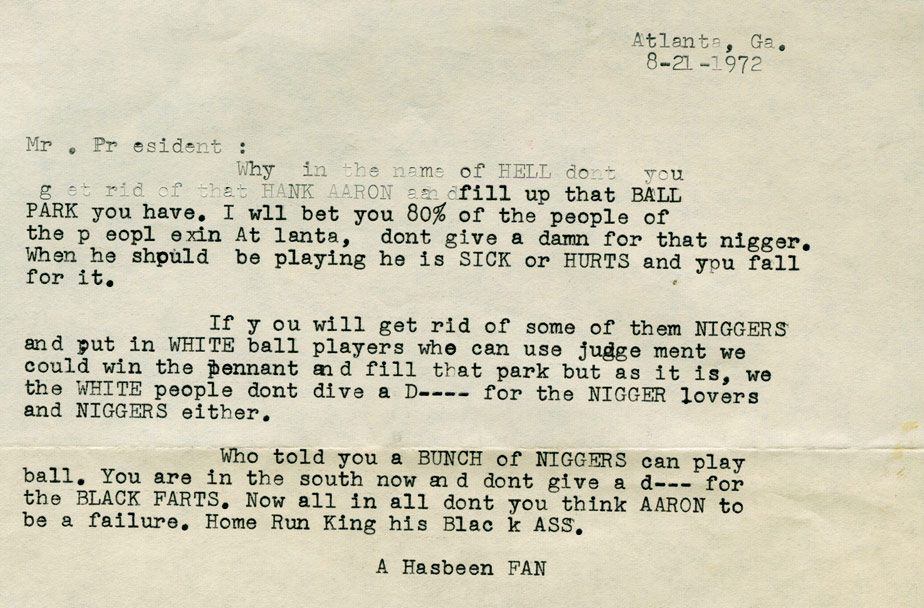

One angry letter sent to management suggests the Braves low attendance records were because of race. Sent in August 1972, it says, "If you will get rid of some of them NIGGERS and put in WHITE ball players who can use judgment we could win the pennant and fill that park."

Aaron originally told reporters he didn't want the team to move from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to Atlanta in 1966. The city was home to Martin Luther King Jr. and a cluster of top-notch African-American Universities, but he felt many Atlanta residents were stuck in a racist past. At the opening game in Atlanta, Aaron says the biggest cheer came after the scoreboard flashed a message that said "April 12, 1861: First Shots Fired on Fort Sumter … April 12, 1966: The South Rises Again." His wife often heard fans call her husband "nigger" from the stands.

Knowing this context, Aaron writes that as "a black player, I would be on trial in Atlanta, and I needed a decisive way to win over the white people before they thought of a reason to hate me."

He decided home runs would win them over. That year, he led the National League with 44. By 1972, reporters started asking about breaking Babe Ruth's home run record.

Ruth was considered the guy who saved baseball. The Sultan of Swat’s numerous home runs were such a marvel (in 1920 his 54 home runs beat the home run total of all but one team that year) and he was such a colorful character that fans flocked to the stadiums to see this power player’s swing. Up until then the fans had been staying away, disgusted by the Black Sox scandal, when players for the Chicago White Sox conspired with gamblers to intentionally lose the 1919 World Series. Ruth restored people’s faith in the game.

As Aaron got within reach, a popular bumper sticker popped up around Atlanta that read "Aaron is Ruth-less." Hate mail poured into the Braves office.

Aaron says he didn't read most of it but kept it as a reminder. It made him hit better, he wrote. "Dammit all, I had to break the record," he writes in his autobiography. "I had to do it for Jackie (Robinson), and my people and myself and for everybody who ever called me a nigger."

The FBI also investigated several death threats and kidnapping plots against his children. An armed guard started accompanying Aaron. Somehow he was able to stay focused.

Hank Aaron talks to CNN's Terence Moore about breaking Babe Ruth's home run record.

"I've always felt like once I put the uniform on and once I got out onto the playing field, I could separate the two from say an evil letter I got the day before or event 20 minutes before," he told CNN. "God gave me the separation, gave me the ability to separate the two of them."

The hate left its mark, though. Even long after he retired, Aaron still scanned crowds for threats. And it does leave him wondering if he could have hit more. "That is one thing I often think about," Aaron told CNN. He says the FBI wouldn't let him open his mail for at least two or three years. Because of the threats, he says he missed his kids' graduations, and they had to have police escorts at school.

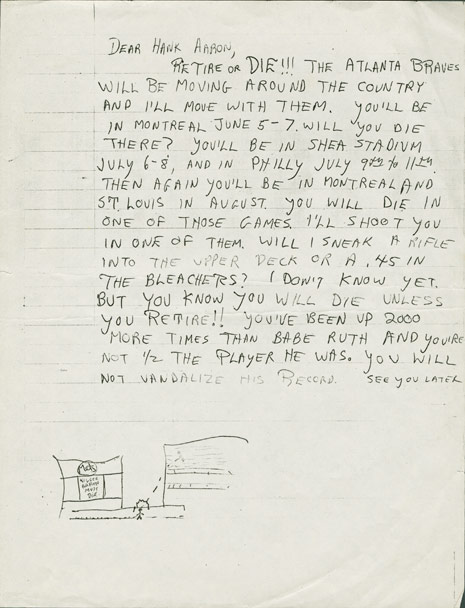

This is another piece of hate mail Hank Aaron received as he got close to breaking Babe Ruth's home run record, many of the letters included death threats, the FBI investigated several of these threats. Aaron and his family were so threatened they were protected by armed guards. From the Richard A. Cecil Collection, Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, Emory University (MARBL).

When the press wrote about his hate letters, positive letters started pouring in. Fans at away games started giving Aaron standing ovations. And finally, a couple home runs shy of the record, at his last home game of 1973, Braves fans stood and cheered for five minutes.

Aaron writes "I couldn't believe I was Hank Aaron and this was Atlanta, Georgia. I thought I'd never see the day," he writes.

With the first swing of his 1974 season, Aaron tied Babe Ruth's record at 714. Vice President Gerald Ford made a speech.

Back at the Atlanta home opener, nearly 54,000 fans greeted him. Sammy Davis Jr. was in the stands as was Jimmy Carter, then Georgia's governor and America's future president.

He hit his record-breaking home run during his second time at bat. The Braves had been playing the team that brought Aaron his hero, the Dodgers. Aaron's entire team greeted him at home plate. So did his mother. "I tell you to this day, I don't know how she managed to do it… but she got to home plate quicker than I got to home base," Aaron said.

A small celebration stopped the game, and all Aaron said was "I just thank God it's all over."

President Richard Nixon called, and thousands of positive telegrams arrived. "Having integrated sports in the Deep South, Aaron already was a hero to me as I sat in the stands that day," President Carter said recently in marking this 40th anniversary. "As the first black superstar playing on the first big league baseball team in the Deep South, he had been both demeaned and idolized in Atlanta."

Carter believes Aaron's success in baseball played a huge role in advancing the cause of civil rights. "He became the first black man for whom white fans in the South cheered," said Carter. "A humble man who did not seek the limelight, he just wanted to play baseball, which he did exquisitely."

That night, Aaron got down on his knees and prayed. "I probably felt closer to God at that moment than at any other time in my life," he would later write.

Aaron retired in 1976 and became a Hall of Famer in 1982. He went on to work in the Braves front office as the vice president of player development and then became the senior vice president and assistant to the president. At 80, he runs the Chasing the Dream Foundation, which gives children mentoring and financial support to follow their dreams.

Reflecting on his accomplishments despite all the obstacles, Aaron said it was his motto that got him through: "Always keep swinging."

CNN.com sports contributor Terence Moore contributed to this report.