The most trafficked mammal you've never heard of

JM for CNN

I went undercover in Southeast Asia to learn why a bizarre, scale-covered mammal -- which has been called a walking pinecone and a modern-day dinosaur -- is trafficked by the ton. It could go extinct before most people realize it exists. You voted for me to cover this topic as part of CNN's Change the List project.

By John D. Sutter

John D. Sutter is a columnist for CNN Opinion and head of CNN's Change the List project. Follow him on Twitter, Facebook or Google+. E-mail him at ctl@cnn.com. The opinions expressed in this story are solely those of the author.

.Cuc Phuong National Park, Vietnam (CNN)

Inside a metal vault here in rural Vietnam is a creature believed to be the most trafficked mammal in the world. No sounds come from its cage. No squeaks or howls. A padlocked door creaks open to reveal an animal that seems far too unassuming to be traded by the ton.

It looks like a ...

"Dragon,” I say.

"Artichoke,” says a colleague.

"His name is P8," a researcher says.

But everyone calls him Lucky.

If you hear his story it's easy to understand why.

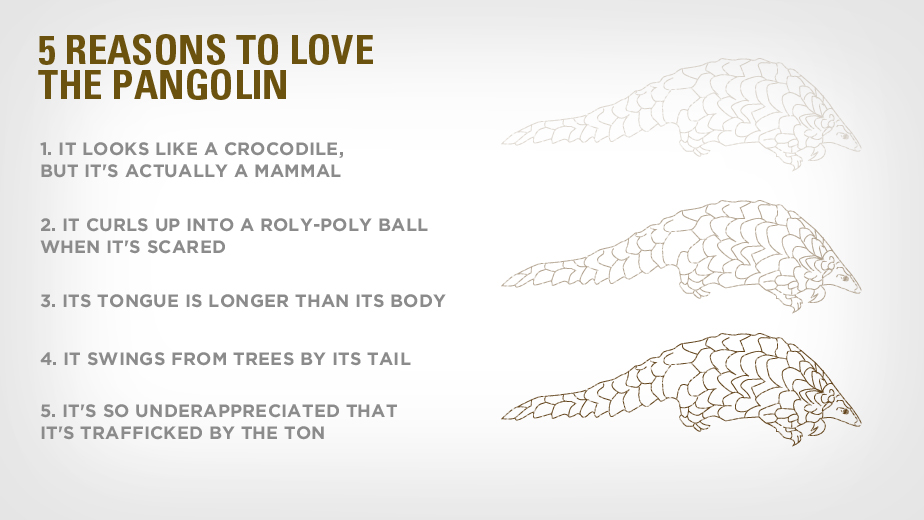

Lucky is a pangolin -- a rare, scale-covered mammal, about the size of a house cat, that’s so bizarre it almost forces your brain to flip through a Rolodex of more-familiar images. It could be described as a walking pinecone or an artichoke with legs – a tiny dinosaur or friendly crocodile. The pangolin possesses none of the cachet of better-known animals that are hot on the international black market. It lacks the tiger’s grace, the rhino’s brute strength. If the pangolin went to high school, it would be the drama geek -- elusive, nocturnal, rarely appreciated and barely understood. When it's frightened, it actually curls up into a roly-poly ball.

The pangolin could go extinct before most people realize it exists.

Or, more to the point: It could go extinct because of that.

Pangolins -- two species of which are endangered and all of which are protected by international treaty -- are trafficked by the thousands for their scales, which are boiled off their bodies for use in traditional medicine; for their meat, which is a high-end delicacy here and in China; and for their blood, which is seen as a healing tonic.

"It's almost like, 'You've got a pangolin you've got a brown bag lunch -- and also a medicine chest,'" said Crawford Allan, director of TRAFFIC North America and a pangolin lover. (He's got a wooden carving of a pangolin in his office in Washington.)

The numbers are astounding. By the most conservative estimates, 10,000 pangolins are trafficked illegally each year. If you assume only 10% to 20% of the actual trade is reported by the news media, the true number trafficked over a two-year period was 116,990 to 233,980, according to Annamiticus, an advocacy group.

No one knows how many pangolins are left in the wild.

But scientists and activists say the number is shrinking fast.

Some experts say the pangolin is likely the most trafficked mammal in the world. It’s impossible to say for certain, of course, because poachers don’t exactly submit spreadsheets on their activities. But aside from pangolins, only elephants would come close to the most-trafficked title in terms of total numbers, said Dan Challender, co-chair of the pangolin specialist group at the International Union for Conservation of Nature and a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Kent.

Yet, few seem to care. International environmental groups and governments have been slow to fund pangolin research and rescue. You don’t see them on the cover of National Geographic. You rarely find them in marketing campaigns. On a two-week trip to Vietnam and Indonesia, I did come across a few pangolin enthusiasts who have dedicated their lives to saving these curious creatures.

DIGITAL DOC: Inside the illegal animal trade

Video by John. D. Sutter and Edythe McNamee/CNN

The activists and researchers are doing amazing, helpful work.

But they have vastly inadequate support.

On this trip, I wanted to figure out why that’s happening -- and what might be done to stop the pangolin from going extinct. After meeting Lucky at a pangolin rehabilitation and rescue center in Vietnam, I set out to trace his path in reverse. How does a pangolin end up in the illegal trade in the first place? Who runs these operations? What are their motives? How could the trade be shut down? The journey would take me to restaurants and medicine shops where pangolin is sold; to meet with mafia-type pangolin bosses (one of whom offered to sell me -- me who wears hipster glasses, isn’t buff and looks nothing like he belongs in the wildlife mafia -- three tons of pangolins, live); and ended with me running around the forests of Sumatra, Indonesia, learning from poachers exactly why and how they hunt pangolin.

It's possible you've read this far and still are thinking: Why does this matter? That's a question -- and I probably shouldn't admit this up front -- I found myself asking again and again on this trip. It nagged at me from one location to the next, like a thorn stuck in my side. But if you want to understand pangolins -- or the illegal wildlife trade in general – it is perhaps the essential question.

It's the one I needed to answer.

I'd never heard of pangolins.

I got weirdly obsessed with them only after CNN readers voted last year for me to cover illegal wildlife trafficking as part of my Change the List project, which focuses on bringing attention to bottom-of-the-list issues and places. When I started calling up experts on this topic, I had no idea what they were talking about.

Have you heard of the pangolin? one wildlife expert asked by phone.

Ummmm, I said, frantically typing into Google.

How do you spell that again?

The more I learned, however, the more I fell in love with this awkward underdog. Do a quick YouTube search (P-A-N-G-O-L-I-N) and I'm sure you will, too.

Among the gems you'll find:

- Baby pangolins riding around on their mothers' tails.

- Pangolins sticking out their tongues, which are longer than their bodies. (The tongues can be longer than a foot, and they actually start at the pelvis.)

- Chinese pangolins roaming around with ears that look almost human.

- African pangolins toddling on their back legs, like mini-T-Rexes.

- And my favorite: Pangolins rolling up into scale-covered balls to protect themselves from lions and tigers, which just bat at them, seemingly confused.

Pangolins, it turns out, are pretty much invincible in the wild.

We're their only credible threat.

When the door opened to Lucky's cage, he didn't appear to be alive.

He was just this nautilus of rust-colored scales, all spiraled up in a ball inside that underground metal box, which was connected by a concrete pipe to his cage, or "pangolarium," as it's called here at Cuc Phuong National Park.

I'd arrived at the park late that morning after driving about 3½ hours from Hanoi, past enormous gumdrop mountains and flooded rice paddies that reflected perfect rectangles of sky when the sun peeked through the rain. Phuong Quang Tran, a researcher who introduced me to Lucky, met me at the gate of the Carnivore and Pangolin Conservation Program, just outside the park. The setting reminded me of the TV show "Lost," with person-sized ferns and aging concrete buildings covered in moss. The gate at Pangolin Rehab, as I'll call it, is topped with barbed wire. Hidden cameras perch on the property like birds of prey.

With pangolins, it turns out, you can't be too careful.

I had to dip my boots in two vats of chemical disinfectant before I was allowed into the pangolarium. This was for the pangolins' protection, not mine.

"We don't know why they die," Phuong said matter-of-factly.

But it happens frequently in captivity.

Lucky is the biggest and friendliest pangolin at Cuc Phuong National Park in Vietnam. He weighed only 4 pounds when he was seized from the wildlife trade. He now weighs 17 pounds.

JM for CNN

These pangolins have avoided a major cause of pangolin death -- poaching -- because they were found in shipments that were intercepted by the Vietnamese government, bound for markets in Hanoi or, by road, to China.

Here, they face new threats.

Maybe it's the food that kills them, Phuong said. There's not been enough research on what pangolins eat in the wild to know for certain what their caregivers should feed them in captivity. Pangolin Rehab has been relatively successful with a combination of frozen ants (25%), soy (35%) and silkworm larvae (50%).

Yet they still have occasional digestive problems.

And the stress of captivity alone can be fatal.

It's one reason you rarely -- almost never, actually -- see them in zoos.

(The San Diego Zoo is the only one in North America that has a pangolin. His name is Baba. The zoo used to have two pangolins, but one died of digestive problems, according to Jenny Mehlow, a spokeswoman for the zoo.)

It's hard to overstate the amount of stress that trafficking routes put on pangolins. They're not happy travelers. Often they haven't had food or water for days and are perilously dehydrated. Forty percent die within a day or two of arriving at the center, Phuong told me. The rest are injected with hydrating fluids and kept in quarantine until they can be moved to a larger cage.

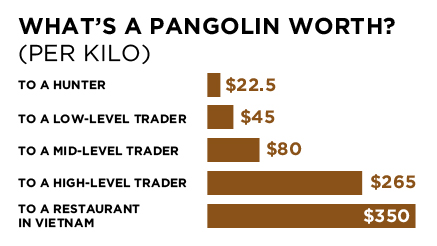

Sources: TRAFFIC, South Africa and IUCN. Note: Rhino numbers are for South Africa only.

All of this made me a little nervous to meet Lucky.

After standing there for a minute, I saw him breathing. It was hard to notice at first, but the hexagonal scales on his back rose and fell in a slow, oceanic motion. He must have smelled us, because his slender, toothless snout started to peek out of the ball like a cobra rising from a snake charmer's basket. Soon, he was looking at us with curious blueberry eyes, bobbing his head and sniffing the air.

The photographer, who asked not to be identified in this story because he lives in Vietnam and fears retribution, got right in his face -- SNAP SNAP SNAP -- and Lucky just kept investigating the scene, putting his nose right up against the lens.

"He's performing," Phuong said with a smile.

After Lucky had a few dozen photos taken, a worker from Pangolin Rehab picked up the pangolin -- wait, what? -- and passed him over to me. I tried to refuse at first, but I could tell this was happening whether I wanted it to or not.

He felt like a lump of bricks in my arms, and a squirmy one. He's one of the biggest pangolins in the world in captivity, Phuong told me. He weighs about 8 kilos, or 17 pounds. Lucky wrapped his girthy pangolin body around my forearm, scales and claws pinching my skin, and held on tight. His stomach was warm and hairy, a somewhat awkward reminder that this otherwise reptilian-looking thing is actually a mammal. His body clamped around my arm like a giant snap bracelet.

"Careful, he's very strong," Phuong said.

I could tell. This animal must have the abs of Pink.

And, this is embarrassing, but I kind of wanted him off of me.

Partly to have my arm back.

And mostly because I didn't want to drop him.

I'm bad at holding babies.

Just think how much I could stress out a pangolin.

After meeting Lucky, I sat in the office at Pangolin Rehab with Phuong and rattled off what I thought would be a ridiculously softball list of questions about pangolins:

- How long do they live?

- How big do they get?

- What's their gestation period?

- What do they eat in the wild, and how much?

- Are they solitary or do they live in pairs?

Phuong, who has talked about pangolins at international conferences, couldn't answer any of these with specificity. No one can. It's known that pangolins can live up to 20 years in captivity, for example, but it's not clear exactly how long they live in the wild. Pangolins eat ants, termites and various larvae, but it's also possible they consume bee larvae, flies, worms and crickets, according to a 2007 technical review of pangolin diets and husbandry. Estimates on their weight range from 4 to 72 pounds.

Pangolins are a near-complete scientific mystery.

And it's not hard to see why if you keep poking around.

Next question: What's your annual budget?

Answer: $27,000.

That includes a staff of seven, the rehab program at Cuc Phuong National Park, and a program to release pangolins at Cát Tiên National Park in the south of Vietnam.

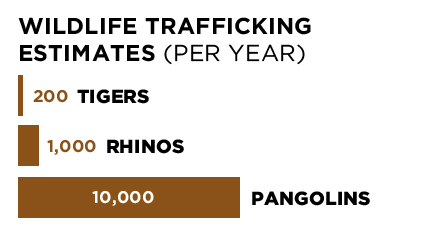

A waitress in Hanoi, Vietnam, shows how pangolin is prepared. Pangolin sells for as much as $350 per kilo.

John Sutter/CNN

"You find pangolins, and I'll give you money." That's what Ruslan, 58, says he was told by a wildlife trader from out of town.

John Sutter/CNN

Pangolins are traded by the ton, frozen and alive. They're sometimes mixed with frozen fish or snakes as cover.

Courtesy TRAFFIC Southeast Asia

Governments and international conservation organizations tend to put their muscle behind "charismatic" species like the rhino or elephant, which are seen in zoos worldwide and are universally beloved.

But pangolins, as a volunteer at Pangolin Rehab, Thai Van Nguyen, explained it to me, are "not a very attractive species -- not beautiful, not colorful.

"Some people -- Western people -- think it's a crocodile."

It's true that more attention has been coming the pangolin's way recently. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature hosted World Pangolin Day on February 15, the day before I left for Vietnam. The main celebration seemed to be rallying support online. Some news organizations -- from Yale Environment 360 to the BBC -- have posted videos and articles. And, out of dumb luck and because he's a nice guy, I somehow persuaded the creator of that "honey badger" YouTube video to make a new (hopefully) viral video about pangolins as part of this story.

But the pangolin, as writer Richard Conniff put it, is still "obscure" at best.

In the public mind, it's definitely no rhino.

When I tell people about pangolins, they often think I'm saying "penguin" with some newly acquired Paula Deen accent.

Perhaps no one would miss a species they never knew existed.

The Pangolin Rehab researchers and others don't see it as an accident that we know so little about pangolins. It's a bias, and I agree. The International Union for Conservation of Nature says the sunda pangolin population (which includes Lucky) likely has declined by 50% in recent years -- but nobody knows what baseline the species is starting from. An update is due out later this year, but the only thing clear about pangolin science is how little of it is being done, and that's because so little of it is being funded. What we're left with is anecdotal evidence, like the stories I heard from Thai in Vietnam. He grew up here, not far from Cuc Phuong National Park, and remembers seeing pangolins outside the park when he was a kid.

Now, he said, it would be impossible to find a wild pangolin anywhere nearby. You could sit outside all night -- night after night -- and never, ever see one.

I spent two nights at Cuc Phuong National Park, and the longer I stayed the more I started feeling like a pangolin. That's weird, I know, but it's not entirely without precedent. A few years ago, children's author Anna Dewdney (if you have young kids, they probably know her "Llama Llama" series) visited Cuc Phong to see pangolins before she wrote the book, "Roly Poly Pangolin," about a shy animal that learns to make friends. She based it on her experiences at the park.

"They're like little tiny dog dragons," she told me. "They look like dragons but they're completely nonaggressive and when they get to know you they're very friendly. They're very shy. They're like small children. So they don't warm up to you right away but once they know you, they bond."

Her boyfriend recommended she look into doing a book on pangolins because he'd read about them somewhere, and they reminded him of her.

Dewdney's awesome, so she didn't take offense at that.

"As a small child, when I felt overwhelmed or terrified of situations, what I would do is go off by myself and draw. I would go to my room and shut the door. And it's still what I do. I can't live in a city because of the constant barrage of things and people. I live in Vermont where it's generally very quiet.

"When I feel overwhelmed, I shut the door and be by myself in my own little safe world. Pangolins do that at any given moment. They just curl up into a ball and they are in their own little world in that way. Literally, they look like a little round planet."

A little round planet. I love that.

Pangolins are trafficked by land and sea in Southeast Asia and China. As supplies dwindle in the region, pangolin is also being sourced from Africa, experts say. Source: Education for Nature Vietnam

I'm not much of a visual artist, but I think almost anyone can see a bit of themselves in those stories. I was an awkward kid, bad at baseball, good at gymnastics; I think all of us encounter situations in which it might be advantageous to curl up into a ball of armor and safely wait out the world. I would feel that way later on this trip, in Sumatra, meeting with the mafia-esque wildlife traffickers.

At Cuc Phuong, I stayed in what seemed like an abandoned building. There was no heat, and the windows didn't shut all the way. I felt like a pangolin as I burrowed under all the blankets I could find, trying to stay warm during the 40-degree nights, curling up in a ball.

My first night in the park, I stayed up late to try to see one of the nocturnal pangolins in action. It's difficult to glimpse them because they emerge from their burrows for only several minutes at a time and then return to safety.

I was lucky enough to catch a pangolin known only as P21 rummaging about that night. This pangolin, I learned, was quarantined for three years (three years!) not because she was sick but because the center didn't have enough money or room to move her into the larger pangolarium. The night I saw her, she seemed to want to release some of that pent-up energy.

At first, all I heard was a sound -- the clanging of a fence, which sounded like a person banging on a typewriter. I looked up to see P21 skittering across the chain-link cage. She seemed to be enjoying herself, running up the fence, across a tree branch -- then, suddenly, up my thigh. She looked at me cockeyed for a moment and then went back to her rounds.

All that was cute, but P21 won me over when she latched her back legs and muscular tail onto the fence and levitated into the air -- her entire body stretched out horizontally, her claws reaching forward in a Superwoman pangolin pose.

She stayed that way for quite a long time, sniffing the air.

She probably was looking for ants, but I imagined her wanting to fly.

A pangolin with a dream.

The next night, I saw Lucky in action.

Phuong brought an ant nest and propped it up in his cage. It wasn't long before he smelled the ants. I heard him sniffing the air -- SNNNF SNNNF SNNNF -- like the sound a motorized air pump makes when you're topping off a car tire's pressure.

Lucky's not as quick-moving as the other pangolins, but there was something magical about seeing him in his element -- out in his cage at night.

I found myself smiling ear to ear, laughing for no reason.

It's usually true that the more time you spend trying to get to know someone, the better you identify with him or her, and the more you like each other.

That was the case with Lucky and me. I learned -- when he wasn't attached to my arm -- that Lucky is the only pangolin at Pangolin Rehab with a nickname. He got it from Thai, the spiky-haired, motorcycle-riding volunteer who rescued him from a warehouse in December 2006, after the government seized 60-some pangolins. Officials told Thai, as he recounted it to me, that he only could rescue the five pangolins that weighed the least. Pangolins, like cocaine, are sold by weight. And the officials planned to resell the heavier pangolins at auction to benefit the government.

(That corrupt but formerly legal practice has since been discontinued, a government environmental official told me. He did not deny that such auctions had taken place in the past. Environmentalists would prefer the pangolins be euthanized so they don't go into the illegal market and end up feeding demand for the animals.)

Lucky was one of the smallest pangolins.

Totally expendable.

And that's precisely why he made it.

Time-out for a quiz:

Is the pangolin your spirit animal?

Answer yes or no to these five questions.

- You sleep all day and party all night. (Partying may or may not include swinging from trees by your tail and/or eating ants).

- When confronted with an awkward situation, you run away and hide.

- You're not so sure about that whole "pairing off" thing. #solitarylife

- You get so stressed out that sometimes you could just, I mean, like, die.

If you answered yes to any of these questions then -- congratulations! -- you might just be a pangolin person. Maybe it's best to keep this to yourself ...

T here were six pangolins when I arrived at Pangolin Rehab and five by the time I left.

Thankfully, none of them died of journalist-related stress.

But one of them, P26, did leave for a new home.

His car arrived around 4 a.m. I met Phuong around 3 to watch him get the paperwork ready. The previous day, he'd affixed a radio-tracking device to P26's tail by drilling two holes in one of his scales. P26 is doing what Phuong hopes all of the pangolins here will eventually do: He's going back to the wild, to a national park in the south of Vietnam, where the climate is warmer and the threat of being hunted is a little lower.

So far, the Carnivore and Pangolin Conservation Program has released five pangolins in Cát Tiên National Park. Researchers are trying to prove such releases are viable, but three of the pangolins have lost their tracking devices (Phuong put P26's lower on his tail, in hopes that might help) and one of their transmitter batteries died. In January, one of the pangolins that had been released died as well.

It's unclear what exactly happened, Phuong said.

His guess?

Stress.

"It's a very sad story."

That was Phuong's favorite pangolin, the liveliest of the bunch.

Lucky, one of the other pangolins that's gotten to him personally, likely will never be released into a park, Phuong told me. The researchers give the pangolins tests to see if they're ready for release. They hide their food, bury it slightly underground, monitor them more closely. The goal is to see if they're ready to fend for themselves in the wild -- or if they've gotten accustomed to life in captivity.

Lucky could never pass, Phuong said.

He wouldn't dig for the food. He waits to be served.

He's too used to humans.

Phuong Quang Tran prepares to put live ants in a dish for a pangolin named Lucky.

JM for CNN

I kept my headlamp on as I followed Phuong past the vats of foot disinfectant and to the quarantine cage where P26 was waiting. Phuong helped move him into a wooden box he'd made by hand. It's the kind of animal carrier you'd expect to see in a cartoon: holes on the side for air, packing slip attached to the top.

P26 would be driven to Hanoi, then flown to Ho Chi Minh City, and then driven to Cát Tiên National Park, where he would be released, on March 17.

I could tell Phuong was worried as he watched the car disappear in the pre-dawn darkness. "OK, good luck to you!" he said in a singsong way that sounded almost like a prayer.

I was told later by Louise Fletcher, who handles pangolin releases at Cát Tiên National Park, that researchers put P26 out in the park inside a box, opened it, and waited for him to run. This was no "Free Willy" moment. He didn't budge.

So they left the box out there overnight, hoping this pangolin -- thought to be the shyest of all these Morrissey types -- finally would get up the nerve to leave.

I said goodbye to the Pangolin Rehab center early the next day, thinking how lucky I was to have met some of these amazingly bizarre animals, each with its own personality and characteristics. P8 is huge. P26 is shy. P21 is an acrobat.

None is just like the next.

There's something wonderful about encountering a creature you had no idea existed, and that millions of years of evolution helped create. The earliest pangolin fossils date back to the Eocene epoch, 35 million to 55 million years ago, shortly after the dinosaurs went extinct. It once was thought that pangolins were most closely related to anteaters, sloths and armadillos. New evidence, however, suggests they may be more similar to carnivorans, a diverse group of animals that includes cats, civets, dogs and pandas. All eight species of pangolin, four in Africa and four in Asia, are in the order Pholidota, which is made up entirely of pangolins. The name pangolin comes from a Malay word meaning "one that rolls up."

Just realizing they're alive -- and in such an otherworldly form -- has a certain magic to it. And then there are all the little surprises -- that P21 can levitate; that P8's sniffing sounds like a DustBuster; that their scales feel like balsa wood; and that they can cover their eyes and ears so ants don't crawl in while they're eating.

They're curious little bastards.

And I developed an unlikely fondness for them.

Which made the next leg of my trip all the harder.

From Cuc Phuong National Park, I drove to Hanoi, a bustling, old-world city that's overrun by honking motorbikes and old women wearing cone-shaped hats. The city is known for its spicy pho, or noodle soup, which customers eat while sitting at plastic, outdoor tables sized for 2-year-olds. The soup is lovely. You often don't have to order. Just sit down and a bucket-sized bowl arrives in no time, clouds of steam rising from the broth.

There's little chance you'll be served noodle soup with pangolin.

The meat is far too expensive.

To eat pangolin, you have to go looking.

And you need lots of cash.

With the help of a wildlife crime investigator from the group Education for Nature Vietnam, I went out in search of restaurants that sell pangolin meat. I was a little nervous about this for several reasons: It's illegal to buy and sell pangolin; I was filming with a hidden camera; and I really didn't want to eat a pangolin.

My editor, however, did want me to order it -- both to prove that it's possible and to find out what it tastes like. What if it's delicious? she asked before I left.

I squirmed at the thought of it.

Like I'm going to come back proclaiming pangolin the new pork belly?

The first stop we made was at a high-end restaurant with a regal-looking lion etched into its window. The entryway was lined with fish tanks, and the hostess stood beside a fan of peacock feathers fashioned into a kind of indoor palm tree.

All of the waitresses were dressed alike: sherbet-orange blazers and gold polka-dot dresses. One showed us a menu. In the "wild animal" section, near the back, was a picture of a live pangolin. (Imagine, for a moment, a U.S. menu with an image of a live chicken on it -- well, outside the show "Portlandia.") It was labeled clearly -- and the "appetizing" preparation options included: "blood wine," "stir-fried pangolin skin with onion and mushroom," pangolin "steamed with ginger and citronella," pangolin "steamed with Chinese traditional medicine"; and, for the unadventurous, the people who would rather eat pangolin at Chili's, there's "grilled" pangolin, too.

Pangolin could be prepared in about 30 minutes, a waitress said with a smile. You have to order it whole, at a minimum of 5 kilos (11 pounds). Price: $350 per kilo.

Or $1,750.

(Maybe it's best to split it with a group).

I considered ordering it right then, although I wondered how I would account for an endangered-animal meal on a CNN expense report.

Sir, it seems you've exceeded your per diem limit.

Traditional medicine has a long history in Vietnam and China. Pangolin scales are made of the same material as fingernails but are claimed to help with lactation issues and other ailments.

JM for CNN

I talked it over with Z, the wildlife investigator who was my tour guide and whose identity I'm withholding because he continues to investigate the wildlife trade in Vietnam undercover. He suggested that I not place the order – or that he didn't want to be a part of it if I did. I'd be giving a substantial amount of money to a black-market industry, he said. And I'd also be ensuring that one specific live pangolin (I thought of Lucky in this moment) would end up dead.

That last part didn't quite make sense to me.

I figured pangolins, like chicken or whatever, would already be dead in a meat freezer in the kitchen. Consequently, I figured I could argue (to myself and to you) that I hadn't actually killed a pangolin by ordering it. It was already dead.

See! Not my fault!

But that's not how it works.

As the waitress explained, with the poise of a "Downton Abbey" cast member, the staff would bring the pangolin out to the table live -- and slit its throat.

Right in front of us.

Think of it as a quality assurance measure, designed to prove to us that we indeed were eating real, endangered pangolin. Not a substitute.

Won't the blood get everywhere? I asked, realizing that's probably not a question a genuine pangolin eater would actually be concerned with. No, she said, giggling. Of course it wouldn't. And we'll serve the blood to you with wine if you'd like.

Rattled by this -- they slit its throat at your table?! -- I asked for more info about the preparation methods. Another waitress, within earshot, approached us with her phone. This is what it looks like, she said, pulling up a photo of a pangolin lying on its back on a plate, stubby little legs sticking up in the air, claws curled under.

Was this served here? I asked.

Yes.

Have you ever tasted it?

Yes.

What does it taste like?

Delicious.

I needed to think this over.

Thanks, I said. Maybe we'll be back.

"What does pangolin taste like?"

Super-scientific poll results:

- Like the absolute best thing you've ever tasted. (This remark came from another waitress in Hanoi. I pressed for details on what the "best thing you've ever tasted" actually tasted like. She looked confused by this.)

- "It's chewy, like chicken."

- "It tasted like chicken."

- Gamey, like duck. "Good, but not too good." Good enough that you would eat it again? "No, I have hypertension."

- "It tastes like ants."

One man was served pangolin at an end-of-year university party.

Another ate it not to blow his cover as an investigator.

In November, the Vietnamese government issued a decree bumping pangolins up to the highest category of legal protection, banning any use, sale or possession of live or dead pangolin, according to Do Quang Tung, the government's director of CITES, the United Nations treaty that governs trade of endangered species of plants and animals.

The maximum penalty, he said, is $25,000 or seven years in prison.

Strike two for eating pangolin, right?

Maybe not. Enforcement doesn't exactly sound rigorous.

At another restaurant, the waitress actually told me ordering pangolin is legal.

And here's an excerpt from my conversation with Tung:

Me: "When I was in the country recently it was fairly easy to find stores selling pangolin scales and restaurants selling pangolin meat. I'm wondering what your comment is on that. It was my impression -- and it's the impression of some environmental groups -- that this material is sold fairly openly."

Tung: "This selling is not allowed in Vietnam."

Me: "Does it happen though?"

Tung: "No."

Me: "It's something that I saw there firsthand ..."

Tung, backtracking: "Yes, of course there have been some restaurants or some areas selling that, but it's illegal now."

"Of course there have been." More like there are. I found pangolin meat for sale in three restaurants; pangolin scales for sale in three traditional medicine shops; and a disturbing pangolin product on display at a fourth restaurant in Hanoi.

All of this was in a matter of hours.

At the fourth restaurant, we saw four glass jars displayed prominently on the back wall of the dining room. Three of the jars were covered in red velvet, and all were under spotlights. With the permission of the wait staff, but without identifying myself as a journalist, Z and I pulled back the cloth on the covered jars.

Floating lizards, bear arms, king cobra. And pangolin.

Floating in rice wine. The pangolin's tongue hung grotesquely out of its mouth.

No way I'm drinking that, I thought. (And it would be impossible now, I'm told, since the pangolin wine was removed after Z reported it to the police).

But the next day, we did go back to the throat-slitting restaurant.

Composite menu of endangered wildlife:

For Hanoi, Vietnam; prices according to Z and other staff at Education for Nature Vietnam, unless otherwise noted; all health benefits are, of course, alleged but unproven and irresponsible:

- Rhino horn: ground into a powder and used to cure hangovers, cancers and to remove toxins from the body. According to a report in The Guardian, a rumor that a former Vietnamese official was cured of cancer by eating rhino horn drove up demand and helped ensure that the last rhino in Vietnam was poached. The cancer connection has no basis in fact and no roots in traditional Chinese medicine, that report says. Price: $50,000 to $60,000 per kilo.

- Tiger bone glue: Made into a gelatin with other animal parts, including those from serow, a type of goat, and macaque monkey bone; used allegedly to relieve pain, treat bone disease and improve male sexual performance. Price: $10,000 per kilo.

- Tiger penis wine: Claimed to improve sexual performance. Price: Unknown.

- Bear bile: Allegedly cures skin disease, including discoloration from bruising; claimed to heal broken bones; seen as a general health remedy. Price: $1 to $6 per cc.

- Pangolin: Eaten as a delicacy and to show off. Price: $250 to $350 per kilo.

- Pangolin scales: Ground up and eaten as an alleged treatment for lactation issues, blood circulation problems and cancer. One prescription I received: Grind up four scales per day and eat them with rice. Continue for seven days. It might taste funky, but just add sugar. Price: $600 to $1,000 per kilo.

- Pangolin tongue: In China, I'm told by a separate investigator, pangolin tongue (yes, that foot-long tongue) is dried and carried in a person's pocket as a good luck charm, kind of like a rabbit's foot. Price: unknown.

- Pangolin fetus: Eaten for alleged health benefits. Price: unknown.

There are plenty of ways to rationalize a pangolin purchase.

Here in Vietnam, it's a sign you've made it. The country is still communist -- red flag, yellow star -- but its economy, like China's, has opened up and boomed in recent years. Status culture has followed. I saw at least three couples in Hanoi taking their wedding photos -- like their actual, for-real wedding photos, white dresses and the whole bit -- in front of the logo for a Louis-Vuitton store.

Eating rhino horn, tiger bone or pangolin meat has a similar effect.

We're rich, y'all. Take a look.

Who cares whether the animal is rare, right? The point is it's expensive. Like eating other exotic animals, it's a "VIP-only" experience, one pangolin eater told me.

The argument is different for pangolin scales. They're sold for about $600 per kilo in clear plastic bags in traditional medicine shops in Hanoi. Dried and curled, they look like seashells or pork rinds. Not exactly appetizing. But a history spanning thousands of years emphasizes the use of pangolin scales to cure lactation issues in women. When I went into these shops, I was also told the scales, when ground up and eaten with rice, can solve blood circulation problems and cure cancer.

It's not about status, it's about alleged healing.

It matters less whether this actually works (keep in mind pangolin scales literally are made of the same material found in fingernails) than that people believe it does.

Neither of those arguments works well for me.

I'm not a member of the Vietnamese nouveau riche.

And, thankfully, no one's asking me to lactate.

The more persuasive argument is that I've eaten rare animals before.

This hunting dog in Sumatra, Indonesia, has been trained on the scent of pangolins, which are difficult to find at night.

John Sutter/CNN

Pangolin scales are sold in traditional medicine shops like those found in an old quarter of Hanoi.

JM for CNN

Pangolin fetus is an unproven aphrodisiac.

Courtesy TRAFFIC Southeast Asia

On assignment for CNN in Alaska, for example, I ate walrus stew, with hair still on the chunks of blubbery meat; and dried seal meat, which I dipped in "seal oil."

I didn't seek out a walrus- and seal-eating experiences. But I was staying in remote indigenous villages, and families were kind enough to offer these dishes to me. I thought it would be unthinkably rude to refuse.

Why not just buckle down and order pangolin?

These thoughts ran through my mind as Z and I went back to the first restaurant and sat down at a table. There was a dark part of me that wanted to eat a pangolin.

Who isn't curious about the new or forbidden?

What does it taste like?

The preparation method didn't actually matter that much to me. In a way, it's more honest and ethical to watch an animal's throat be slit in front of you than to pretend, as most of us do in America, that worse things don't happen in factory farms, far outside our restaurants and kept, intentionally, far from sight and mind. We're big hypocrites when it comes to animals in America, and I'll include myself in that assessment. I've always been a meat eater, but I have given that up, at least temporarily, following this reporting trip. People here in Hanoi eat dogs, which we'd never dream of doing. But Americans eat pigs, and they're just as smart and loving.

For pangolins, what matters is that they're rare.

And they're faced with the prospect of extinction.

I thought about Lucky. I understood the consequences of ordering pangolin, both for an animal I'd weirdly come to care about -- and for a criminal enterprise that's linked in with other nasty networks. One pangolin boss in Vietnam is nicknamed "Iron Face," and she's thought to deal in other illicit goods as well. Some pangolin bosses are known to trade rhino horn, for instance. (The last Javan rhino in Vietnam was poached in 2010, according to World Wildlife Fund. Now, as few as 35 individuals remain, all of them outside this country.) Other wildlife crime networks have been linked to Al-Shabaab, the East African militant group that the United States identifies as a terrorist organization, and to the smuggling of arms and drugs, which even people who aren't animal lovers can agree is bad.

It's selfishness and ignorance, all of it.

Because I knew all that, I couldn't stomach pangolin.

I wanted to -- for the thrill of it, mostly, and for the story -- but I couldn't.

Z and I got the pho instead.

It's impossible to say exactly where Lucky and the other trafficked pangolins in Vietnam came from. But there's reason to suspect Indonesia, the 253-million-person nation made up of thousands of islands that straddle the equator.

In August 2013, nearly 7 tons of pangolins from Indonesia were seized at a port in Haiphong, Vietnam. In 2008, almost 14 tons of pangolins, frozen, were seized in Sumatra, the westernmost island, likely bound for Vietnam or China.

The man responsible for that 14-ton bust -- I'll call him Q to protect his identity -- picked me up at the airport in Sumatra. He's a put-together guy who wears button-up shirts, parts his hair in the middle and listens to jazz.

He also leads a double life.

He works as an undercover wildlife investigator for an international organization.

His young children think he's unemployed.

Q has been able to pull off that deception because of personal connections. Someone in Q's network (I'm not saying exactly who) once was a tiger-trading and slaughtering kingpin. Ask him about it and Q matter-of-factly says that this man is partly responsible for the fact that there are only 400-some tigers left in Sumatra.

But Q is making good on that connection. He uses his link to a now-deceased trafficker to get access to criminal wildlife-trading networks.

And then he shuts them down.

He's had a surprising amount of success.

I asked Q to help me understand the supply side of the pangolin trade. Where do the pangolins come from, and how are they shipped for export?

He towed me into that world, which felt at times like I was being pulled into an episode of "CSI" or "Weeds." I hoped the whole thing wouldn't end up like "Locked Up Abroad" -- me in jail, or worse, left in the hands of cutthroat traffickers.

Q wasn't too reassuring on that front.

At breakfast before we set off to meet with one of the pangolin mafiosi, he dropped on the table a jar containing a dead, baby pangolin floating in a yellow liquid.

A trafficker we were going to meet gave this to Q as a gift, he told me.

Q plays every situation, dangerous or not, with a smile and a joke. But Q knew I would be taping the interview with two hidden cameras.

He knew what could happen if this guy noticed.

"Big boss," he kept telling me in heavily accented English. "Big boss."

Subtext: Don't end up like that pangolin in the jar.

Encounters with pangolin mafia, incident 1 of 2:

The first member of Sumatra's wildlife-trading mafia who Q helped me meet looked like Barack Obama -- cropped hair, coffee skin, a toothpaste-commercial smile. That lightened the mood a bit. I walked past his spiked gate, up the driveway and into his living room, which has a large rug with a lion's head on it.

The trafficker, whose identity I'm withholding since I did not identify myself as a journalist, displayed a strange fondness for pangolins for someone who admitted to buying them from hunters and arranging their transport to larger cities. (Q told him that I also was involved in the illegal wildlife trade in order to hold his cover).

He built an entire room for pangolins in his house, in the Lebong district of Sumatra, but he couldn't keep them inside, he told me.

The good news: Some former hunters are now trying to protect the pangolin. The bad news: Pangolin is easy to find on menus in Hanoi. Some restaurants slit its throat in front of customers.

JM for CNN

In February, a restaurant in Hanoi kept this pangolin floating in rice wine. CNN reporter John Sutter was told it was removed after authorities were called.

John Sutter/CNN

They kept digging their way out through the tile floor.

"Oh, I think this animal is very smart!" the trafficker said, lighting up.

This man seemed to think pangolins had video-game-like powers. He told me the pangolins tried to escape from his house by curling up into balls and then spinning with Sonic-the-Hedgehog speed to burrow through the floor.

He said they can hide underwater for upwards of 15 minutes without air.

And he told me their blood has magical healing properties -- four of them.

"My boss says if you want to make medicine from pangolins, you take rice wine and boil it with a baby pangolin, and put it in a jar," he said in a local dialect, which I recorded and had translated later. "You don't have to mix it with other ingredients, you just boil it with the wine and you put it in a jar. Every morning you drink one small cup -- and it can heal you from disease. There are four ways it will help: First, for skin disease. Second, it will make you always feel fresh. It will help you breathe easily (that's three) … and I forget what the fourth reason is."

I would let the four-reasons thing go, except that he kept going with it: "I guarantee you, if you drink that wine, you will get healed from those four diseases."

Right, four.

He said he's gotten out of the pangolin trading business recently because it's risky to ship them. He was trying to move pangolins by car from his town to Palembang for export (usually to Vietnam, he said). The car's tire popped on the way and police threatened to confiscate the 1-ton load of pangolins in the back. "We had to pay about 300 million (rupiah, or $26,000) to get the pangolins and car out of there," he said. He laughed about the bribe.

Police threw in a free spare tire as part of the deal.

"With money," he said, "you can make everything easy."

There was a time, perhaps a decade ago, when pangolins were so common in some parts of Indonesia that people literally hit them with their cars. Three such car-pangolin crashes were described to me on my trip.

From them I can draw two conclusions:

- This never happens anymore because pangolins are so rare.

- Pangolins are tougher than cars.

None of the pangolins died on impact. The drivers said they checked.

Encounters with pangolin mafia, incident 2 of 2:

"Would you like to see the snakes?"

That's a question that, in normal life, I would always say no to … 100% of the time. But on assignment in Sumatra, in a wildlife trafficker's living room, I had to say yes.

I kind of wanted to say yes.

The trafficker, the one who gave Q the pangolin in a jar, looked like every drug dealer you've seen cast for a U.S. TV series -- surfer shorts, button-up, short-sleeve shirt, slouchy-but-I'll-kill-you demeanor. He led me into his back hallway and opened the door to what appeared to be (or formerly was) a bathroom. Dozens of rice sacks were tied at the top and each, from my understanding, contained a live python. I didn't quite believe that until this man grabbed one of the bags and dumped out a 12-foot python at my feet -- my bare feet, by the way.

I jumped like a meerkat -- directly over the snake, which was slithering at me, and fast. The trafficker and my translator thought this was pretty hilarious.

Where do you go from there except back to the sitting room to talk about trafficking pangolins? From my chair by the door, I could see the trafficker's kids around the corner watching TV and playing with little-kid toys. One (no joke) was holding a helium balloon in the shape of a panda, an endangered animal.

Q explained to me later that this trafficker uses pythons as a cover for his pangolin shipments. He puts them on top, because pythons can be shipped out of Sumatra with a permit and under a certain quota. I asked the trafficker if I could see a pangolin (this was probably overly bold in retrospect) and he declined.

But he did make an offer.

"Yes, there are plenty of pangolins here," he told me, thinking that, because I'd come with Q, perhaps I wanted to strike up a deal. "If you have enough money, for one month, I could supply you with two or three tons" of pangolins.

He asked for an inflated price – the Chinese price, he said.

Three tons for about $790,000.

Some time ago, he would have accepted maybe a third of that.

But it's getting harder to ship pangolins out of Sumatra, he said, both because there's more police presence (thanks probably to the bust Q orchestrated in 2008) and because customers in Vietnam and China now demand live pangolins, for slaughter at the table, and live pangolins are more difficult to pack into cars and drive around.

Tellingly, none of that means the trade will stop -- it just means it's more expensive.

"I have connections at every level of the police force in the region," the trafficker said. "I have to pay them every month -- about 15 million" rupiah, or $1,300 total.

Learn to speak trafficker! In addition to having their own nicknames -- "Iron Face," "Golden Scales" -- wildlife traffickers also speak in their own code language.

A key, courtesy of Q:

- "08" = whole tiger

- "Yellow bamboo" = ivory

- "CB" = rhino horn

- "TH," or "tonti" = pangolin

- "Jacket" = tiger skin

Ketenong, population 580, is squished between two picturesque national parks in South Sumatra Province. That makes it prime poaching territory.

No one here cared about pangolins -- never gave them a thought -- until a few years ago when a wildlife trader from Bengkulu came to town. Ruslan, a 58-year-old who used to hunt pangolin, remembers the man well -- and what he promised.

"You find pangolins, and I'll give you money."

Simple enough.

So Ruslan did.

A wiry man with porcupine hair and a raspy, Joan Rivers voice, Ruslan worked in the rice fields by day, then climbed into the forest at night to hunt pangolin. He didn't know it was illegal, but he got quite good at it.

Some pangolin hunters say they're just trying to support their families. They use the money to buy milk, not luxury items.

John Sutter/CNN

Ruslan, 58, and another pangolin hunter, Ropi, a 29-year-old who wears a pink backpack, showed me one night what it's like to go on a pangolin hunt. Both men told me they're not currently hunting pangolin, but they took me into the forest to show me how it's done. I asked them not to actually trap any pangolins on my behalf.

Let me just tell you, pangolin hunting is hard work.

A few notes from my journal entry that night:

"Holy s***! That's work! Trudging through mud that's shin deep. There could be tigers or rhinos to chase you down. Looking for an animal some consider satanic. When you hit it with a flashlight (which we didn't) it looks like a ghost -- you see its red, beady eyes. Crossed rivers I don't know how many times.

I don't know why I didn't lead with the leeches. I only got one leech stuck to my shoulder, but my traveling companions all had more. One had seven. We were out in the forest for maybe two hours, patrolling like security guards with flashlights. It's almost impossible to watch where you're going and look for pangolins, which means you're often sliding down mud-covered mountainsides, getting stuck in tangles of ferns and vines and plants with spikes on them. I reiterate: This is hard.

"The second hunter climbed up a slippery cliff, hoisting himself up vines, chopping down other vegetation with a machete. The first grabbed my hand to pull me up to a (pangolin) nest -- shone light on the "tracks," which were so faint in the Martian red mud that I couldn't see them even with his guidance."

Ruslan helped me understand the experience by summing it up this way:

"If we were rich people, we wouldn't want to go into the forest to hunt pangolin."

We didn't find a pangolin, but the experience was enlightening. Pangolin hunting is the worst. And it hasn't made Ruslan and Ropi rich. They're not motivated by greed. They're not buying fancy cars -- any cars -- or big, showy houses. I went in both men's homes. Ruslan's cache of electronics includes a (non-smart) cellphone, a small TV and a rice cooker. Ropi lives in a humble wood home that appeared to have two rooms. Their village only got electricity two years ago -- and many rice farmers here only earn the equivalent of about $2 per day. This is a desperate place. Ropi told me he only considers going out to hunt pangolin again when he sees his two young children, a boy and a girl, and realizes that, without the extra income from the hunt, he doesn't have enough money to buy them milk.

People in this part of Indonesia once saw the pangolin as cursed.

Find one in your house and someone in your family might die soon -- or the house might burn down. Some people, according to Q, even believed that pangolins were mystical, almost satanic. If lightning struck, they could disappear in a flash.

Now those beliefs are gone.

International demand has infected this place.

"I think when you find the pangolin you are lucky," Ropi told me.

"You can change the pangolin (into) money."

Estimated value of a pangolin:

To a hunter in Indonesia: $18 to $27 per kilo

To a low-level trader in Indonesia: $45 per kilo

To a mid-level trader in Indonesia: $80 per kilo

To a high-level international trader: $265 per kilo

To a restaurant in Vietnam: $350 per kilo

I told one of the hunters, who had been getting $18 to $27 per kilo for pangolin, what restaurants in Vietnam charge. "Wow! That's a very fantastic price!" he said.

Then he thought about it.

"I think that's unfair."

My thinking about pangolins got caught in a loop after visiting the hunting village of Ketenong. Is better enforcement of the law the solution? I didn't like the idea of cops arresting people like Ropi and Ruslan, the men in the food chain with the least to gain, although I did hear that the threat of arrest is an effective deterrent.

Enforcement should focus primarily on the international networks – on breaking down the barriers that insulate the real players in this trade from arrest.

Part of that means rooting out corruption.

Part of it means hiring more people to patrol the forest. Rangers I met told me their numbers in Sumatra are ridiculously inadequate to protect wildlife here.

But what about other solutions? Education? It seems like a hard sell to think that explaining to people why pangolins are important -- something I have enough difficulty articulating after nearly two weeks of talking about them -- would suddenly change the minds of big-boss wildlife traffickers or ground-level poachers.

At least that was my skeptical view before I met a man named Suryatin.

Suryatin has managed almost singlehandedly to turn a village of pangolin hunters into pangolin protectors. And he's done it by gently coaxing people to Do the Right Thing by supplying them with better information about pangolins.

"If the forest is destroyed, life is also destroyed," he told me.

"Enforcement isn't effective out here. People need to know why you're not allowed to hunt pangolin," he continued, before offering the most concrete ecological argument for the pangolin's importance I'd heard. "Next door is a rubber plantation. Sometimes the ants eat the rubber trees. Why that happens is because there are no more pangolins -- so because of that, I try to convince people to let the pangolins live.

"Letting the pangolins live can help the rubber trees survive."

Where was this guy two weeks ago?

It's not just about the rubber trees, of course.

Suryatin, 63, and the 1,260-person town's mayor, Yendra, actually buy pangolins back from poachers if they see them leaving town to sell to a collector. They pay full market price, he told me, or about $22, because he cares that much about pangolins -- and because he sees it as a teaching moment. He takes the opportunity to explain to the would-be poacher that pangolins are unique and valuable -- a cornerstone of the local ecosystem, and that many industries would unravel without it.

"I just talk about why I care about wildlife and pangolins," he said, as if that's the simplest and most why-didn't-you-know-that solution ever. "People who buy the pangolins don't understand the benefits of the pangolins for nature."

It's working, but not for exactly the reasons he thinks.

I met one former pangolin hunter, Zainal Abidin, 54, who had one of these confrontations with Suryatin. He used to track pangolins by sound -- listening for the CRRRUK CRRRUCK CRRRUK of their scaly tails rattling against the tree branches -- before spotting them with a flashlight and, sometimes, clubbing them on the head. He told me he heard Suryatin's arguments about the pangolin's ecological value, and he understood. "Pangolins are interesting animals," he said. "Pangolins are just like humans; if the pangolin goes extinct it will affect the humans, too." But there were other factors in his decision to stop poaching: He is getting older, for one, and hunting pangolin is hard. Jail time is part of it, too.

But he also found another job.

When the economic incentive to hunt went away, it was no longer a consideration.

Education is an important part of the solution, but people also need jobs.

That's certainly something Suryatin can understand.

He got on this enviro kick several years ago when he received training from World Wildlife Fund, to start a tree nursery to help in reforestation efforts. He's done very well for himself, planting 5 million trees since 2003, he told me. He ended up buying the land across from his greenhouse because it's home to an enormous "root tree" where pangolins are known to nest, and where people used to hunt them.

If he owned the land, he thought, he could stop the poaching.

Ropi, a 29-year-old in Sumatra, Indonesia, said he has hunted pangolins to feed his kids; not to get rich.

John Sutter/CNN

The root tree is a sight -- a tangle of vines that's easily three stories tall and as wide as a small house. Think of the tree from "Avatar" or something out of "Fern Gully."

It's that spectacular.

Suryatin calls it -- and I'm not kidding -- "The Tree of Life."

I had no idea I would meet Suryatin when I traveled out to his village, which is called Karang Panggung and is the closest thing I can imagine to a Sumatran enviro-utopia.

I thought I was traveling there to go on another pangolin hunt.

But that's not happening here anymore -- not much at least.

I talked with several people who expressed Suryatin's enthusiasm for nature. And I kind of fell in love with the place. I spent part of an afternoon taking photos with kids who were playing volleyball. They practiced their English on me: "Good morning I love you!" Almost every home seems to have potted trees out front, because many residents are helping in reforestation efforts.

So, instead of going on a pangolin hunt on my last night in Sumatra, I decided to take several people from the village with me to the Tree of Life.

I hoped we could see a pangolin in the wild.

Headlamps and flashlights in tow, we walked over to the tree around 8:30 p.m.

I asked one of my companions what other animals we might find out here. "Oh, tigers and leopards," he said. "You can see leopards in the secondary forest like this."

Great, I thought.

Tigers by dark.

The first hour was marked with lots of activity. One man climbed at least 20 or 30 feet into the tree to look for a pangolin that turned out, fittingly, to be a chameleon, the master of disguise. Some of us paced circles around the tree. Others walked the nearby forest, panning our lights like prison wardens. At one point, there was a faint light moving among the roots. A pangolin eye? Nope, lightning bug.

Around 10 p.m., we decided to have a seat and wait.

"Everyone turn off your flashlights," said Q, who still was traveling with me.

"Let's try being silent."

The next hour and a half was one of the most magical periods of my trip to Southeast Asia. I looked around, checking for pangolins and leopards, then lay down on my back and listened. The jungle will play music for you if you let it. An owl hooted on the upbeats; birds in the distance sounded like they were shooting lasers in video games; frogs squeaked like chew toys; and something behind my right ear sounded roughly like a car with an ignition struggling to fire.

(Please be a tiger. Don't be a tiger.)

The longer we were quiet, the more layers of sound revealed themselves. Sumatra is home to incredible plants and animals -- to elephants, rhinos, orangutans and the largest known flower in the world, Rafflesia arnoldii, with a bloom 3 feet across. All of those icons of nature are featured on national park brochures and Wikipedia pages. But in the echoing silence of that night, I was reminded of why the diversity of life matters.

The insect string section. The faint WHOOP WHOOP of the gibbon.

All of them are needed for the song to continue.

We've discovered and named perhaps 10% of the species that exist on this incredible planet, according to Harvard biologist E.O. Wilson. The unknowns are mostly the little guys -- the fungi, bugs and microbes. For me, the personal list of "unknowns" included the pangolin. It was new to me at the start of my journey.

Who doesn't want to live in a world where those discoveries are possible -- where the planet is full of possibility and wonder?

The alternative is awful: Knowing that we live in a place that is continually getting less diverse, less interesting, less capable of supplying humanity with scientific discoveries and medicines and better/stronger materials.

And, most importantly, less capable of supporting life.

The planet, like the pangolin, is surprisingly fickle.

"As extinction spreads, some of the lost forms prove to be keystone species, whose disappearance brings down other species and triggers a ripple effect," Wilson wrote in his 1992 book, "The Diversity of Life." "The loss of a keystone species is like a drill accidentally striking a power line. It causes lights to go out all over."

Perhaps that could be the case with pangolins.

Too little is known to be certain.

But everything in the natural world is connected. All of it matters. As one wildlife crime expert, Crawford Allan, put it to me: What's the point of saving Mona Lisa's smile if the rest of the painting is gone? That's the perfect metaphor for what's happening with the wildlife trade. Advocates have become so focused on nature's celebs -- the rhinos, the elephants, the tigers -- that they've neglected the bigger picture.

It's easy to ignore a species like the pangolin.

But we do so at our peril.

At first, lying there on the ground, I was telepathically willing a pangolin to emerge from the dark. Come on pangolin -- this would be the perfect way to end this story. Us meeting out here in the wild, under the "Tree of Life" no less. I need an ending here!

But the more we waited, the more at peace I was with the idea that I likely never will see a pangolin in the wild. Right then, under the tree, that seemed perfect. Not just OK, but better. I knew from what Suyratin and the others had told me that at least two pangolins actually do live in the tree. If they're smart enough to hide from us, they're probably better off than the pangolins in Vietnam, whose developed need for attention has cost them their freedom. These pangolins are wise -- and they're lucky. They live in a village where, even if they did present themselves, they would be protected. People here realize the world is a better place with the pangolin -- a little stranger, a little more wonderful. They're protected because they're understood.

That's the best the lowly pangolin can hope for.

And that's actually quite a lot.

About this story

In 2013, more than 30,000 CNN.com readers voted for columnist John D. Sutter to cover five social justice issues as part of his Change the List project. The illegal wildlife trade is the third of five issues readers selected for the series. Upcoming stories will focus on water scarcity and childhood poverty. A sixth topic will be chosen by CNN's editors, based on your suggestions. This is journalism as democracy. For more, follow Sutter on Twitter and visit CNN.com/Change.

Change the List

You pick it, I'll cover it

Columnist John D. Sutter asked readers in 2013 to vote on their top five social justice issues of our time. Learn more about the vote and how you can get involved in the coverage.

The rapist next door

Alaska's rate of reported rape is three times the national average. John D. Sutter met with politicians, victims — and rapists — to learn why.