The huge industrial park sprawls across the rural landscape with row upon row of warehouse-sized manufacturing units. Logos and signs plastered with red and gold — lucky colors in Chinese tradition — brighten the otherwise gray exteriors while aromas of Peking duck come from an on-site canteen.

But this development is thousands of miles from Beijing or Shanghai — and just a few hours’ drive from the Texas border, in northern Mexico.

With street signs in both Chinese and Spanish and the flag of the People’s Republic flying high alongside that of Mexico, this is one of many “industrial Chinatowns” that have been created in recent years around Monterrey, turning farmland to factories and boosting the local and national economies.

Much of the growth owes to the phenomenon of “nearshoring” — Chinese companies moving production to Mexico to have tariff-free access to the US market under the USMCA trade deal. President-elect Donald Trump negotiated that deal with Mexico and Canada in his first administration but is now threatening tariffs on Mexico and other countries and an “External Revenue Service” to collect dues. With days until the beginning of Trump’s second term, these companies and their Mexican hosts are now planning their options if the trade restrictions come.

Matt Harrison, president of Kuka Home North America, which has a furniture manufacturing base in Monterrey, fears the future could be bleak.

“Simply put, 25% tariff on Mexico puts me out of business,” Harrison said, “We’re waiting to see what happens when Trump moves into office — if we can continue to grow or not.”

But César Santos, who has welcomed much Chinese investment on his land, still sees good business ahead.

“Even with a 25% tariff on Mexican goods, many companies believe it’s still a better option than manufacturing in China,” he told CNN.

From horses to housewares

Santos remembers riding horses up to his family home; for generations, this was a ranch belonging to his forebears.

The old farmhouse still stands but construction is all around — for factories, housing and a hotel.

Santos and his family began developing their 1,500 acres of land in 2013, initially partnering with Chinese shareholders looking to build factories closer to their US customers, Santos said. Trump’s imposition of tariffs on Chinese-made goods entering the US starting in 2018 — which President Joe Biden largely kept and expanded — supercharged the dynamics.

“Actually, that helped us. When they put a tariff there (on) China, then those companies came to us,” Santos said. Firms started with temporary leases but quickly transitioned to purchasing full facilities as other factors came into play, he added.

“From here, we are 160 miles from Texas. So, in 24 hours, 44 hours, the products are in the US from here. This logistics is very important, it is good for them,” Santos said of the incoming manufacturers.

Santos launched a partnership with two Chinese entities to build and manage Hofusan in 2015, creating the industrial park that now has deals to host 40 Chinese companies. The factories already up and running and those set to come online produce everything from electronics to furniture to car parts — all destined for the US.

He and many others have benefited from soaring Chinese investment in Mexico, which has risen from just $5.5 million in 2013 to $570 million in 2022. The first six months of 2024 — the latest period for which figures are available — showed $235 million coming to Mexico from China in direct investment, according to government statistics.

And Santos is staying bullish on the future for companies starting production in Mexico, even if Trump does impose levies on goods as punishment for what the President-elect says is a failure to stop undocumented migrants heading north into the US.

Looking for security against any growth of cartel power as well as to protect his profit, Santos has donated land for Fuerza Civil, the state police, to build a station adjacent to his industrial Chinatown.

He said he likes the incoming US president and admires Trump’s strength and character.

“For all the issues we have in terms of all the criminal gangs and everything like that, the drugs … we need the help of people like him to stop that.”

Combining cultures

Both Mexicans and Chinese are forging new relationships as they try to keep the boom going.

Developer Ramiro González has traveled to China and has his nickname of “Da Long” or “Big Dragon” stitched in Chinese characters on his vest.

“The Chinese culture is that they appreciate time. So, they expect to be fast in everything. So here in Mexico, we have to try to get a better construction process and design process to be faster,” he said.

Earthmovers and building equipment beeped around him as he showed plans for his latest development — another industrial park but this one a little outside Monterrey as he said there had already been so much building there.

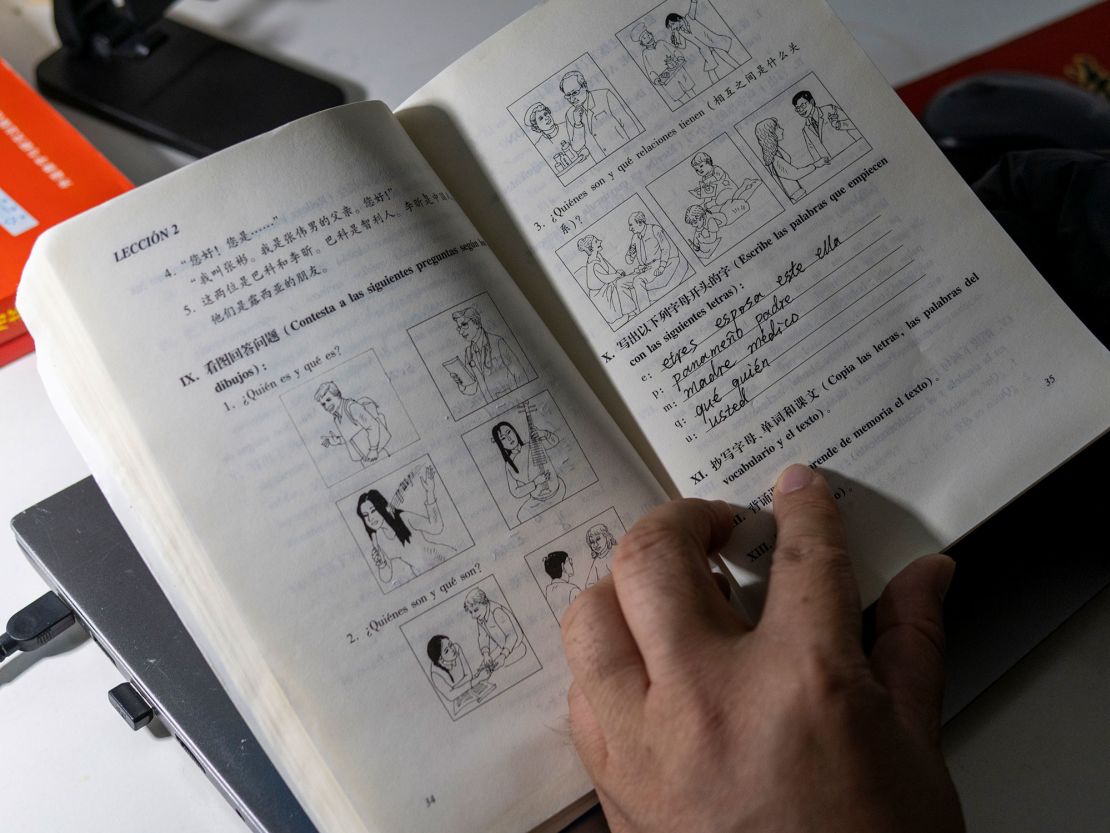

There are, of course, cultural hiccups especially for the incoming workers. Zhang Jianqiu, an engineer who provides services for robotics equipment in new factories, acknowledged he was homesick living halfway across the world from his family. He said he and his housemates had to source their preferred type of electric kettles to boil water for the Chinese tea that is brought in by every returning countryman.

But once he started exploring the local culture and cuisine and learning Spanish, he became more settled, said the man known as Lupe to his Mexican friends.

Now acting as a bridge between Chinese companies and the welcoming Mexican communities they invest in, Zhang has a clear view of what tariffs could mean for growth.

“Most Chinese companies are still waiting and watching,” he explained, ”and then they will make a final decision.”

It’s complicated, he said, but also nothing new.

“For Chinese companies, if they want to go global, they have to face different challenges from different countries, not only about tariffs, but also about the policies and regulations of the local country,” he said. “But business is business, politics is politics.”

And despite the tariff threat, Zhang, like the Mexican workers we talked to, said he looked to Trump as a successful businessman who would likely do what makes sense financially and not do anything to hurt the American economy. Economists and CEOs say it’s American consumers that will pay for tariffs as companies pass on the costs through increased prices. And while tariffs on imports could in theory boost domestic manufacturing by making its costs more competitive, there are other factors like consumer demand and interest rates that may make any increased business harder to obtain.

“For a businessman, I think profits are of vital importance,” Zhang said of Trump’s mindset. “Sometimes we may argue before the election to defeat (an opponent) but when he becomes the president officially … I think it will change.”

The Chinese government retaliated to the tariffs of Trump’s first term with their own tariffs but is not directly involved in the shift of individual business operations to Mexico.

In November 2024, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning spoke of China and Mexico as “good friends” and “good partners” and said that would continue. “We always believe that politicizing economic issues serves no one’s interest,” she added.

Mexican workers and Chinese bosses

On the factory floors, as sofa frames are nailed together and cushion covers stitched, Chinese and Mexican customs are combined. The laborers and their managers are mostly Mexican, while bosses are Chinese, breaking down to about 95% local, and 5% Chinese workers, said a representative of Kuka Home.

The Mexicans say their hard-working nature gels with the Chinese expectations of the managers brought in to train them, and the Chinese bosses seem happy, adamant that they abide by local labor rules.

At the Kuka Home factory — located in a facility closer to downtown Monterrey than Hofusan – the assembly lines hum with activity.

A supervisor, Christian Cordero, spoke proudly of their furniture output, which ends up in high-end chains like Crate & Barrel and Williams Sonoma. “90-95% of what we produce here we export. For this reason, we are committed to quality. Mainly, we have to teach people to put quality first, with that culture and then audit it ourselves as leaders and as supervisors,” he said.

His colleague, Eric Espinoza, just three months into his new job, said the industrial Chinatowns had drawn many people to Monterrey.

“This has been a great opportunity. Right now, we have more than 1,100 employees,” he said.

Any tariffs would likely make their products more expensive for US customers, but Espinoza also pointed to another potential impact.

“Without these jobs, many families would be affected,” he said. “If these jobs vanish, crossing the border to find work may be the only option left for many of us.”

Some impacts are already being felt. Harrison of Kuka Home North America has halted construction on a neighboring building that would have accommodated more orders from the US, because, he said, of the tariff threat. Harrison is now exploring sites for further expansion in Vietnam with his Chinese backers. Vietnamese exports to the US also face tariffs, but it’s relatively cheap to manufacture goods there and is seen as a viable alternative.

“Absorbing 25% is not going to happen for any company,” he said. “Who ends up paying for it at the end of the day? It’s us, the American consumer and, to me, that’s immediate inflation.”

Caught in the middle

Horacio Carreón, an assistant professor of international business and logistics at Tecnológico de Monterrey, is focused on the ripple effects that could come with the imposition of new tariffs from the US.

Right now, he’s watching the different messaging techniques between an unconventional President-elect Trump and Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum, who prefers an academic approach to geopolitical issues. But Carreón recognizes this may end up being a matter between the US and Chinese superpowers, with Mexico caught between them, almost like a soap opera.

“That’s like the love triangle that can be attached to a Mexican telenovela, and we’re just in the middle,” he said. Mexico has done well as a business partner for both China and the US as their economies grew but might now be at a crossroads, he added.

“What we’re seeing right now is that Mexico has a very complicated position because they need to assess where should I go next? Should I continue being with my partner of my entire life, which has been the US, or should I start looking elsewhere?”

In recent years, Mexico has experienced record-breaking investment in industrial and commercial construction, according to statistics provided by the Secretary of the Economy. In 2023, it also surpassed China to become the leading exporter to the US.

González’s construction company has been inundated with more interest from Chinese companies hoping to expand in Mexico. He believes there is still plenty of room. “We’ve created spaces for thousands of jobs, and there’s so much potential ahead,” he said. “We just have to see how the landscape shifts.”

And Santos, who saw his family ranch redeveloped into an industrial hub, said he is ready for more change if needed.

“If the US market becomes too challenging, we’ll look to Latin America and beyond.”

CNN’s Steven Jiang contributed to this story.