President-elect Donald Trump’s choice to be the government’s top lawyer before the Supreme Court burst on the national scene about a year ago and is best known for winning Trump immunity from prosecution for election subversion.

But D. John Sauer has been an unswerving, if low-profile, foot soldier in America’s culture wars for more than a decade.

The nominee for US solicitor general has opposed abortion rights, birth-control access and same-sex marriage. He backed efforts to overturn Trump’s election defeat in 2020 and last year was one of the most prominent conservatives arguing that the Biden administration censored right-wing views about Covid-19 and vaccines.

Now, he is poised to become one of the most powerful lawyers in the country, representing the Trump administration before a conservative bench that could be even more open to the president’s agenda than the first time. Three of the nine justices were appointed by Trump during his first term.

The confluence of Sauer’s experience, his personal tie to Trump and the transformed court he will face could lead to some of the most ambitious advocacy on behalf of an administration in decades.

Sauer has already been at the lead of litigation over transgender rights, which was one of the flashpoints of the presidential race and at the center of the most closely watched case of the current term.

Within 48 hours of Trump’s November 14 selection of Sauer for the solicitor general post, Sauer appeared on a previously scheduled Federalist Society panel in Washington entitled “Sex, Gender, and the Law.” He spoke about a case he’d recently appealed to the Supreme Court on behalf of Arizona legislators who want to keep transgender girls and women from playing on female sports teams. (A federal appellate court blocked Arizona’s “Save Women’s Sports Act,” in the case brought by two transgender girls who wanted to play girls’ sports at their schools, finding that the prohibition violated the Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection.)

In the general comments he offered, Sauer emphasized that lower courts are divided over the level of constitutional coverage for transgender people alleging discrimination and that legal battles are bound to continue.

Earlier this month, the justices heard arguments on whether states may ban gender-affirming treatment for children experiencing gender dysphoria, that is, distress over an identity that does not match their sex at birth. The Biden administration had petitioned the justices to take the case after a US appellate court upheld bans in Tennessee and Kentucky.

One of the first challenges for the new US solicitor general will be to alert the justices to a new Trump position. The incoming administration may not want to withdraw the petition or otherwise slow down the court’s consideration of the case, US v. Skrmetti, since the justices appeared ready to uphold the bans.

Sauer declined a CNN interview request for this story.

The 50-year-old nominee is a Harvard Law grad and Rhodes scholar who served as a law clerk for the late Justice Antonin Scalia and eventually became Missouri state solicitor general.

He shunned the sometimes-confining world of corporate law that many lawyers of his pedigree choose. As a result, Sauer, intensely conservative and a committed Catholic, has been able to chart his own course in the law. He remained largely under the radar until the Trump representation.

After his nomination, Rebecca Hart Holder, president of Reproductive Equity Now, a Boston-based national abortion rights group, raised concerns about where Sauer would take the federal government on reproductive rights, for example, related to emergency-room services for pregnant women experiencing complications. The Biden administration has argued in recent lawsuits that the 1986 Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) ensures emergency abortion care.

“The fact that President Trump is nominating a very well-educated conservative attorney who has made attacking abortion rights one of the cornerstones of his career is deeply troubling,” Holder told CNN, “He is an attorney who will go after not just the right to access to abortion but also, really, surveillance of people who could be seeking abortion care.”

During Sauer’s time as Missouri solicitor general, a state health director reportedly gathered information on menstrual cycles and pregnancies. The information emerged in a 2019 hearing over the state’s effort to deny Planned Parenthood a license to perform abortions.

This year, according to Missouri Ethics Commission figures, Sauer contributed $777,000 to the Missouri Right to Life political action committee and two other groups opposed to a ballot measure, known as Amendment 3, to ensure abortion rights in the state.

Among those ready to praise Sauer’s nomination was former US appellate judge Michael Luttig, who otherwise is an unrelenting critic of Trump and the Supreme Court’s decision to give him substantial immunity from prosecution.

Sauer was as a law clerk to Luttig, who sat on the Richmond-based US based appellate court, before Sauer served in the chambers of Scalia, a conservative icon who died in 2016.

“He is a man of great faith and great principle,” Luttig said of Sauer, “He has stayed close to his roots in all respects. He is devoted to his family.” Luttig has declared Trump v. United States a mistake akin to the 1857 Dred Scott decision that denied Black people citizenship. But he lays it at the feet of the justices, not Sauer.

Yet it is precisely the case that has catapulted Sauer to one of the most powerful and prestigious legal positions in any administration.

When Trump announced the solicitor general nomination on November 14, his statement referred to Sauer “winning a Historic Victory on Presidential Immunity, which was key to defeating the unconstitutional campaign of Lawfare against me and the entire MAGA Movement.”

Clerkships and anti-abortion efforts

The SG, as the position is known colloquially, decides which of the government’s legal losses in lower courts to appeal and then defends the administration before the nine justices.

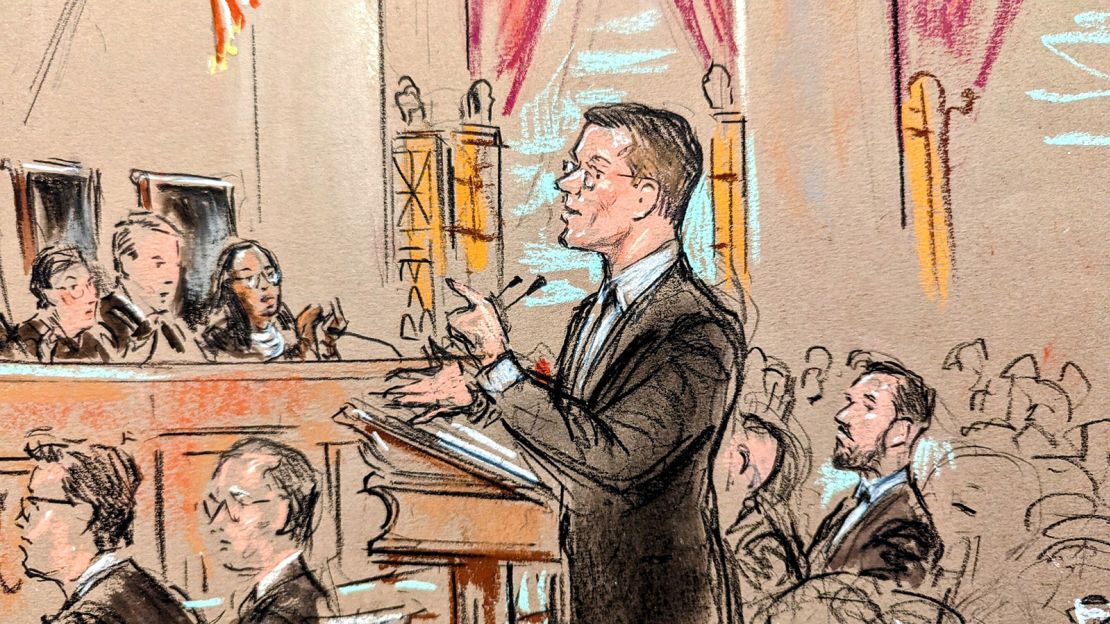

Most visibly, the SG stands at a mahogany lectern, before the nine justices on their elevated bench. The men who have taken the role (and all but two SGs in history have been men) wear the traditional garb of grey morning coat and grey striped trousers.

The post is currently held by Biden appointee Elizabeth Prelogar; the first woman SG was Elena Kagan, who served for a year before President Barack Obama appointed her to the Supreme Court in 2010.

Sauer’s appointment breaks a pattern of SGs chosen from large corporate law firms or high-ranking academic positions. In his first presidential term, Trump chose Noel Francisco of the global Jones Day firm.

After his judicial clerkships, Sauer worked briefly for the small but influential conservative firm of Cooper Kirk, then spent five years as an assistant US attorney in the eastern district of Missouri. He then worked for small firms and eventually founded his own law group named after James Otis, a leading political and legal activist of the colonial era who developed foundational views of a limited government and individual property rights. Sauer was captivated in his childhood by the portrayal of Otis in the Revolutionary War classic work, “Johnny Tremain.”

In private practice, Sauer wrote briefs backing abortion restrictions and arguing against the Obamacare contraceptive mandate.

He represented 67 Catholic theologians and ethicists on the side of Hobby Lobby Stores, challenging the Affordable Care Act’s birth-control insurance regulation for employers.

“The Mandate,” Sauer wrote in the 2014 case, “imposes a substantial burden on the religious freedom of Catholic employers and other religious believers who object on religious grounds to providing insurance coverage for abortifacients, elective sterilization, and/or contraceptives, and for education and counseling designed to encourage the use of such services. … (T)he Mandate thrusts Catholic and other religious employers into a ‘perfect storm’ of moral complicity in the forbidden actions.”

The Supreme Court sided with the challengers in a 5-4 decision.

Sauer also represented members of Congress who opposed same-sex marriage, in a case that eventually led to the Supreme Court’s 2015 landmark Obergefell v. Hodges decision creating a fundamental right to gay and lesbian unions. The following year, he wrote a brief for a group of conservative scholars in support of a restrictive Texas abortion law. The Supreme Court in June 2016 struck down the regulations as an undue burden on a woman’s right to end a pregnancy, in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt.

From 2017 to 2023, Sauer served as the Missouri state solicitor, first taking the position at the urging of then attorney general (and now US senator) Josh Hawley. He joined with other Republican-run states in briefs to the high court against federal Covid vaccine mandates for certain health care workers and against abortion rights, including in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case that led to the reversal of Roe v. Wade in 2022.

During Sauer’s tenure as state solicitor general, he defended Missouri capital cases, including one that went all the way to the Supreme Court. That case, Bucklew v. Precythe, was brought by a convicted murderer challenging the state’s lethal injection protocol. The state won in a 5-4 decision.

The square-jawed Sauer keeps his dark hair closely cropped and wears small oval shaped wire-rimmed glasses. He exudes a buttoned-down restraint but can become animated on all manner of topics.

“He’s a very well-read person with a ton of interests, from the sacred to the profane, almost literally,” said John Demers, who was a co-clerk in the Scalia chambers nearly 20 years ago and has stayed friends through the years. Demers, a vice president at Boeing, was an assistant attorney general for the National Security Division in the first Trump administration.

“He’s a practicing Catholic and we share that piece in common,” Demers said. “He can talk about theology, and he can talk to you about ‘South Park.’”

Sauer’s argument style can be similarly animated with moments of drama.

When he appeared before a federal appellate court in 2023 for the state of Louisiana (after leaving the Missouri SG post) in a challenge to the Biden administration’s social media practices, he spoke rapidly and emphatically.

At one point, his voice intensified with a personal claim that he had been censored after talking about the case in a recorded law office presentation: “The notion that Covid censorship is over is totally unsupportable. Two weeks ago, I gave a talk about this very case … criticizing federal government censorship.” He said the video had been posted on social media but then removed. “I was censored as a lawyer for the Louisiana attorney general,” he said, offering no further explanation nor being pressed on it by the judges hearing the case.

When the social media case later went to the Supreme Court, the justices by a 6-3 vote rejected that position, put forward by two states and five social-media users. Justice Amy Coney Barrett wrote that the challengers had failed to demonstrate that they were injured by any administration actions.

Deep roots in Missouri

Sauer’s first name is Dean, but he has always gone by his middle name of John. He attended a Catholic grade school and then Saint Louis Priory, a Benedictine monk-run boys’ secondary school. He went to Duke on an academic scholarship and became captain of the varsity wrestling team. Before studying at Harvard Law School, he was a Rhodes scholar, attending Oriel College at the University of Oxford.

Sauer’s family goes back several generations in Missouri. He and his wife have five young children. Associates say he is still deciding whether to move the family to Washington, DC.

Sauer’s father, Fred, founded an investment firm and became president of Missouri Roundtable for Life, a cause to which John has contributed. (Fred Sauer ran unsuccessfully for the Republican nomination for governor in 2012.)

John Sauer also contributed heavily to the Missouri Right to Life PAC this year as the group was fighting the ballot measure to establish a right to abortion in the state’s constitution. Voters approved Amendment 3, which overturned a state ban and gave residents a right to end a pregnancy up to the point that a fetus would be viable, that is, live outside the woman.

Since Sauer’s time as a state solicitor general, he has been active in numerous red state litigation efforts.

After the 2020 presidential election, he joined with a handful of other Republican state lawyers to challenge the election results that gave Joe Biden the White House. He shepherded a brief on behalf of six states that sought to intervene in the case first filed by Texas against Pennsylvania and other swing states that favored Biden. (The Supreme Court declined to hear the case.)

Trump v. United States

Sauer came to real national prominence at the end of 2023, when he represented Trump’s defense to charges brought by Department of Justice special counsel Jack Smith, who had accused the former president of election fraud, conspiracy and other offenses that culminated in the January 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol.

He was connected to Trump by Will Scharf, who was working in Missouri with Sauer and has since been designated by Trump to be White House staff secretary.

Scharf recounted a call from Trump in August 2023 in an interview with the Missouri Independent, “His legal team was looking to bring on a dedicated appellate team, and the president just called me and asked me if that was something that I was interested in.” Scharf said he, Sauer, and another lawyer “pitched the campaign the way you would pitch any client, and a couple days later, they hired us. And we’ve been working for the president ever since.”

Sauer presented oral arguments before the DC Circuit and then Supreme Court on behalf of Trump. His ardent claims for presidential immunity extended famously in the lower court even to a situation when a president would order Seal Team Six to kill a political opponent.

Before the justices in arguments last April, Sauer defended Trump on constitutional principles, as well as against the specific details of the election-subversion charges.

When confronted with the allegations that Trump helped create a “fraudulent slate” of presidential electors in the states, Sauer interjected: “so-called fraudulent electors.” He said referring to them as “fraudulent” amounted to “a complete mischaracterization.”

“On the face of the indictment,” he told the justices, “it appears that there was no deceit about who had emerged from the relevant state conventions, and this was being done as an alternative basis.”

He brushed aside any suggestion of wrongdoing by Trump in the states, despite that Smith’s indictment said Trump had “organized fraudulent slates of electors” to “obstruct the certification of the presidential election.” (State prosecutions related to 2020 fraudulent electors are ongoing.)

Sauer told the justices Trump “absolutely” had a right to put forward alternate Republican electors.

More broadly, Sauer asserted, “Without presidential immunity from criminal prosecution, there can be no presidency as we know it.”

It turned out the Supreme Court, where he could soon regularly appear as solicitor general, agreed.