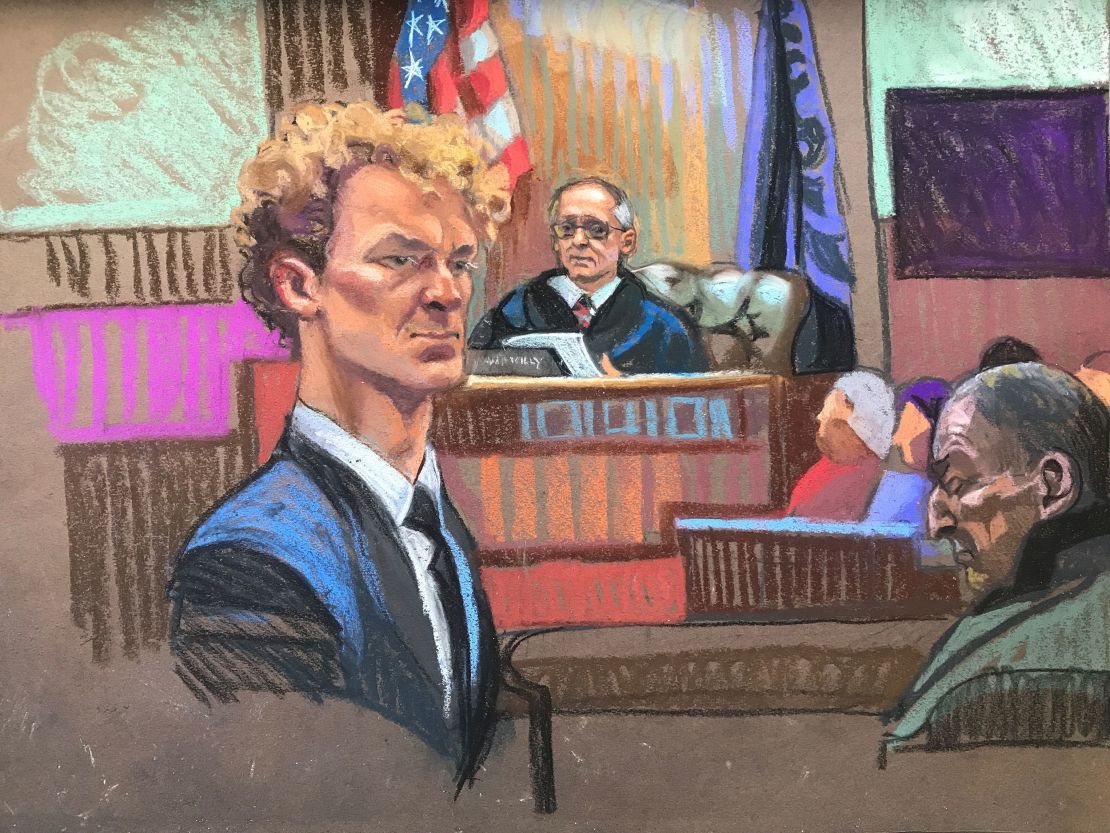

A judge granted a motion from Manhattan prosecutors to dismiss the more serious charge of second-degree manslaughter against Daniel Penny on Friday in his trial over the chokehold death of Jordan Neely on a New York City subway last year.

The ruling clears the way for the jury to consider a remaining lesser charge of criminally negligent homicide. It came after a Manhattan jury said they were deadlocked twice on the manslaughter charge and Penny’s defense attorneys renewed their motion for a mistrial.

Over defense objections, Judge Maxwell Wiley agreed with prosecutors, who argued that dismissing the first count of second-degree manslaughter eliminates the defense’s concern about a compromise verdict.

Penny, 26, a former Marine, now faces a single charge of criminally negligent homicide in Neely’s death, which carries a maximum penalty of four years in prison, significantly less than a potential maximum sentence of 15 years tied to the more serious charge. The judge could also choose to sentence Penny to no prison time if he is convicted.

Penny could not have been convicted of both charges, according to the judge’s instructions to the jury.

Wiley told the jury the second-degree manslaughter charge has been dismissed, functionally allowing them to now consider the remaining charge of criminally negligent homicide.

“What that means is you are now free to consider Count 2. Whether that makes any difference or not, I have no idea,” the judge told the jury after updating them.

Judge Wiley had instructed the jurors to keep deliberating after they were deadlocked on the charge earlier in the day. Penny’s defense attorneys objected and moved for a mistrial over the deadlocked panel of 12 Manhattanites.

After informing them of the manslaughter charge dismissal, Judge Wiley sent the jury home earlier than usual, telling the panel to “think about something else” over the weekend. The jury will return Monday morning to continue deliberations on the remaining charge.

“It’s not time for a mistrial,” Wiley told the attorneys outside the presence of the jury, after the jury first reported being deadlocked.

Shortly before the judge’s ruling, lead prosecutor Dafna Yoran had indicated her office would drop the second-degree manslaughter charge if the jury could move on to consider the lesser charge of criminally negligent homicide.

Defense attorney Thomas Kenniff objected to the motion, telling the judge he was unaware of any legal precedent for the prosecution’s proposal and called it “novel.”

Granting the proposal, Kenniff argued, would “encourage prosecutors’ offices to overcharge in the grand jury.”

Penny’s defense attorney made clear they would appeal Wiley’s decision if the jury ultimately convicts Penny on the criminally negligent homicide charge.

Wiley acknowledged there may not be an explicit precedent for his ruling, telling the attorneys, “I’ll take a chance and grant the prosecution’s application.”

Explaining his rationale, the judge said it is a unique case because typically in an indictment including a lesser charge, there is a “very clear” difference between the counts, but in this case, he said, there is not.

“We are obviously very pleased with the Court’s decision to withdraw the top count of this indictment,” Keniff said in a statement Friday evening. “However, we have always maintained that Danny acted reasonably in restraining Jordan Neely, and justice will not be served until he is acquitted of criminally negligent homicide as well. We are hopeful that will happen when the jury returns on Monday.”

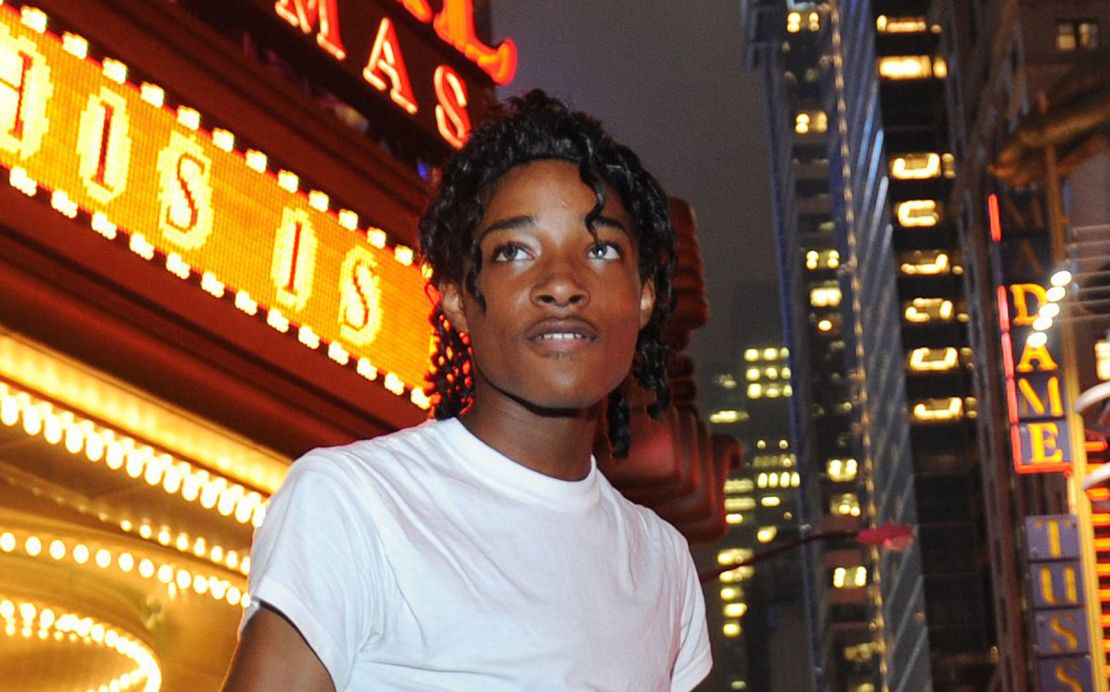

Neely, a 30-year-old street artist who struggled with homelessness, mental illness and drugs, had entered a New York City subway car on May 1, 2023, and began acting erratically. He threw down his jacket and yelled at passengers that he was hungry and thirsty and didn’t care whether he died, witnesses said. Penny, a subway passenger, grabbed Neely from behind in a chokehold, forced him to the train floor and restrained him there for several minutes. When police arrived and Penny let go of the hold, Neely was nonresponsive.

Several minutes of the chokehold were captured on bystander video that quickly went viral. That video, as well as Penny’s interview with NYPD investigators explaining his actions and autopsy findings, were central pieces of evidence in the trial.

“I wasn’t trying to injure him,” Penny told police. “I’m just trying to keep him from hurting anybody else. He was threatening.”

Prosecutors have said Penny acted recklessly by restraining Neely in a chokehold for so long, even after Neely stopped moving, while his defense has said he was acting to protect others from a threat.

The case has polarized NYC residents, many of whom have personal experiences with disorder on the subways, and raised broader questions about mental health, race relations and the line between protector and vigilante. Black Lives Matter protesters have added Neely’s name to its roll call of victims – including just outside the courthouse – while others have praised Penny’s efforts to try to protect others.

In closing arguments Monday, the defense argued Penny “was justified in the actions he took to protect the other riders.”

Neely “was on a collision course with himself” and Penny “acted when others could not,” defense attorney Steven Raiser said during his two-hour closing argument.

The defense also has challenged the medical examiner’s determination Neely died from the chokehold and suggested the charges were brought because of “a rush to judgment based on something other than medical science.”

Prosecutor Dafna Yoran, in her closing arguments, said Penny intended to protect fellow passengers but “he just didn’t recognize that Jordan Neely’s life too needed to be preserved.”

“We are here today because the defendant used way too much force for way too long in way too reckless of a manner,” she said.

What happened at the trial

The trial began with jury selection in late October and has featured testimony, video and 911 calls from subway riders, responding police officers and martial arts and medical experts.

The prosecution called more than 30 witnesses to the stand, including one man who helped restrain Neely’s arms during the struggle and testified he advised Penny to loosen his grip. “I’m going to grab his hands so you can let go,” Eric Gonzalez told Penny, according to his testimony.

Further, Gonzalez could be heard in video footage of the incident saying that Penny wasn’t “squeezing” Neely’s neck in the 51 seconds before he released the chokehold. Gonzalez also testified he initially lied to investigators about what he saw and did on the subway out of fear he would be “pinned” for the killing. Prosecutors promised not to charge him in the case, he testified.

In addition, the Marine Corps martial arts expert who trained Penny in chokeholds testified that Penny was aware the holds could be lethal.

Several subway riders testified they were terrified Neely was going to attack and that they were relieved when Penny put him in a chokehold and kept him there.

“Restraining him for the moment was a relief, but if he would have gotten up, he would have done what he would have done,” subway rider Caedryn Schrunk said.

The defense’s case focused on emphasizing Neely’s threatening behavior, character witnesses from Penny’s time in the US Marines and challenges to the medical cause of Neely’s death.

Penny served four years in the Marines as a sergeant, from 2017 to 2021, with his last duty assignment at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina, according to military records.

The city medical examiner who performed Neely’s autopsy, testifying for the prosecution, ruled the cause of his death was “compression of neck (chokehold).” She made that determination after performing an autopsy and watching the cell phone video on the subway but did not wait for the toxicology report, she testified.

The defense presented its own medical expert who said Neely died of a combination of factors, including a sickling crisis linked to his sickle cell trait, a schizophrenic episode, the struggle and restraint by Penny and K2 intoxication.

The jury began deliberating on Tuesday afternoon. Over the first two days of deliberations, jurors sent several notes to the court requesting to review video evidence and rehear parts of the jury instructions and testimony during the trial.

Separately, Neely’s father filed a lawsuit in New York Supreme Court on Wednesday accusing Penny of assault, battery and causing Neely’s death. Andre Zachery, who is listed as the administrator of Neely’s estate, accused Penny of having caused the death “by the reason of the negligence, carelessness and recklessness.” The suit does not specify the amount of money the family is seeking.

Penny’s defense attorney Kenniff did not respond to a request for comment on the suit.

This story has been updated with additional information.