Americans have spent the last few years complaining about inflation. But price rises in Russia are eye-watering by comparison – and just one symptom of an economy that is overheating.

Butter, some meats, and onions are about 25% more expensive than a year ago, according to official data. Some supermarkets have taken to keeping butter in locked cabinets: Russian social media has shown stocks being stolen.

The overall inflation rate is just shy of 10%, much higher than the central bank anticipated.

Inflation is being driven by the rapid rise in wages as the Kremlin pours billions into military industries and sends millions of men to fight in Ukraine. In the middle of a war, companies outside the defense sector can’t compete for workers without paying much higher wages. In turn, they charge higher prices. So the spiral continues.

“Prices are rising because of the war,” Alexandra Prokopenko at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center in Berlin told CNN. “Demand in the economy is distorted in favor of unproductive spending. Wages rise because employers have to compete for labor.”

Other economists dub this as growth without development. National income grows, but there is no broad improvement to health, education, technology and infrastructure.

In an effort to cool inflation, the central bank raised its key interest rate in October to a record high of 21%. But an influential group of Russian economists said on Telegram this week that “increased inflationary pressure will not only persist but may even increase.”

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin said earlier this month that the Russian economy needs nearly 1 million new workers because of an unemployment rate of only 2.4%, or “virtually no unemployment,” as he put it.

Putin described Russia’s labor shortage as “currently one of the main obstacles to our economic growth.”

“We have about half a million people in construction - the industry will take 600,000 people and not even notice,” he told a think tank summit this month. Manufacturing needed at least 250,000 more people, he said.

High labor costs and interest rates are squeezing companies. Russia’s Alfa Bank said last month that “companies are already having a hard time, and with the (central bank) rate increased to 21%, it will become even more difficult, so we do not rule out the risk of increased bankruptcies.”

Along with most economists, Alfa expects the central bank rate to rise to 23% next month. At the heart of the overheating is the Kremlin’s spending. The military budget will rise by nearly a quarter in 2025, amounting to one-third of all state spending and 6.3 per cent of gross domestic product. Add in other so-called “national security” spending, and it amounts to 40% of the federal budget.

According to the draft budget published in September, defense spending next year will be at least double social spending, which includes benefits and pensions.

Crisis? What crisis?

Analysts don’t see the Russian economy as tumbling over a precipice but instead as a slowly gathering crisis.

“With a steady stream of commodity revenues, a competent economic team and escalating repression at home, the Kremlin can continue funding its war effort for the foreseeable future,” Prokopenko said.

The International Monetary Fund expects Russian GDP to rise 3.6% this year, compared with its 2.8% forecast for the United States.

International sanctions have not delivered a knock-out blow. Russia has evaded sanctions by importing Western technology through third countries, especially through central Asia and Turkey.

And despite all those Western sanctions, EU imports from Russia still totaled nearly $50 billion last year.

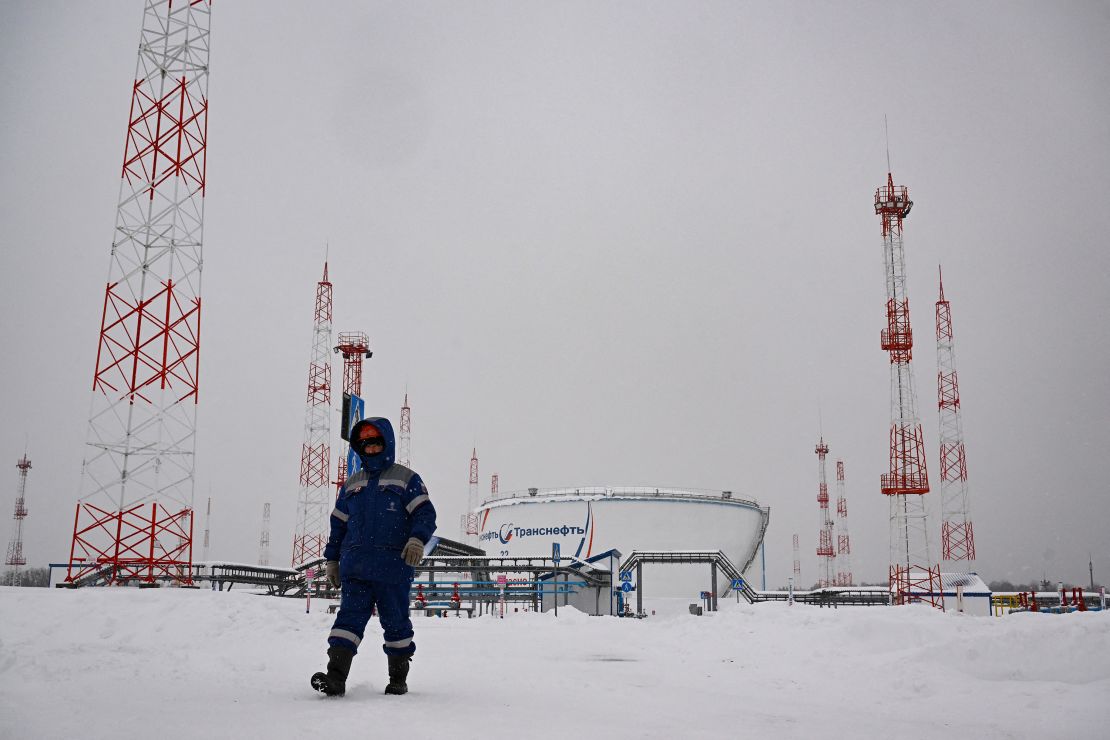

The Russian state continues to reap the benefits of exporting oil and gas to India and China, largely through a shadow fleet of ships that evade a $60 per barrel price cap that Western governments have tried to impose. At home, state receipts are rising, especially through sales tax as Russians spend more.

According to Russia’s State Statistics Service, incomes adjusted for inflation rose 5.8% last year as companies chased workers.

For millions of Russians working overtime, especially in IT, construction and manufacturing, times are good. And the wealthy who used to spend much of their money in European resorts are now spending it at home, further stimulating the economy.

Families are also benefiting from higher pay and bonuses paid to men recruited into the armed forces. Russian contract soldiers are paid nearly three times the average wage and receive a signing-on bonus of anywhere between $4,000 and $22,000.

If they are killed in combat, there is a further payout to their families of well over $100,000 depending on the region, leading a Russian economist in exile, Vladislav Inozemtsev, to conjure the phrase “deathonomics.”

All this cash is helping to drive a spending spree far from the front lines. Official figures show much higher spending on domestic tourism and leisure.

But not all benefit from rising incomes.

Public sector workers, including doctors and teachers, as well as pensioners and social benefit recipients, are the hardest hit by rising prices, Prokopenko said.

And there is no quick fix to the chronic labor crunch.

Russia has traditionally turned to central Asia for unskilled labor, and Putin recently suggested more foreign workers are needed. In 2023, 4.5 million foreign workers came to Russia, mainly from central Asia. Then came a wave of Russian xenophobia following the terror attack in Moscow last March.

“Immigration from Central Asia could therefore fall short of expectations in 2024,” Prokopenko said, “especially as Russia is also competing with the Middle East and South Korea for Central Asian workers. Russia has virtually nowhere else to find new workers.”

And its longer-term demographics are bleak.

The United Nations expects the Russian population to shrink to 142 million by 2030 from just under 145 million now. Its average age is also increasing: Over a fifth of the population is now age 60.

The UK Defense Ministry estimated that some 1.3 million people left Russia in 2022, when Moscow launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, aggravating a 15-year trend of a shrinking workforce. Many of those who left were young professionals.

While it is difficult to be precise about the exodus, the Atlantic Council noted that “if 700,000 Russians now registered as living in Dubai is any indication, the émigrés may number far more than 1 million.”

Despite its surprising resilience over the past few years, the Russian economy is still vulnerable to shocks in an uncertain global environment. Lower commodity prices, a slowdown in Chinese demand for Russian oil and trade wars would all have an impact.

And when the war ends, Russia will have to adapt to a post-war economy, curbing state spending, reintegrating huge numbers of demobilized soldiers and reorientating companies away from feeding military industries.

The big Russian cities are enjoying the fruits of a wartime economy, but there may be a reckoning ahead.