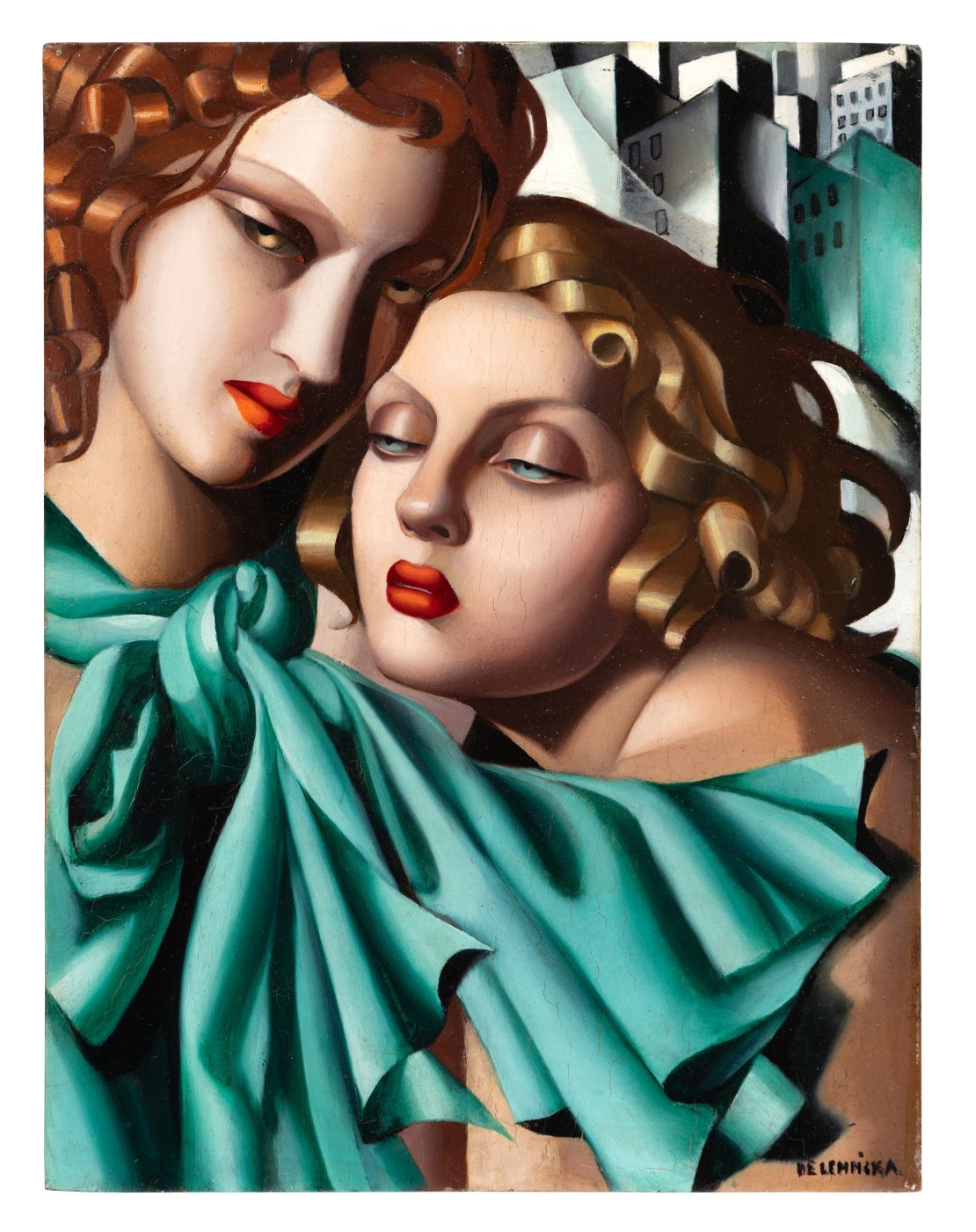

With her portraits of red-lipped women painted like sculptures in resplendent jewel tones, the Polish painter Tamara de Lempicka has posthumously become an Art Deco icon. Her figures are sumptuous and moody, seemingly longing for something more as they pose in front of crowded skylines or behind the wheel of a car, scarves and draped gowns billowing in the wind.

Though Lempicka never found sustained critical success during her lifetime (she died in 1980), she’s collected today by superstars including Barbra Streisand and Madonna — the latter who displayed some of Lempicka’s paintings onstage during her “Celebration” tour last year. Lempicka’s market has soared, with a painting of cabaret singer Marjorie Ferry setting her auction record at £16.3 million ($21.3 million) in 2020. A century after the height of her career, Lempicka’s life and work are fascinating the art world more than ever.

Lempicka has never received a major museum retrospective in the US — until now. A new show at the de Young, a part of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, will showcase more than 150 works.

“She captured optimism as Europe was rebuilding itself after the First World War,” explained curator Furio Rinaldi — who organized the show with art historian and Lempicka biographer Gioia Mori — in a video call with CNN.

“There was an electrifying sense of hope (for) a future and world where women had a new role; they entered the workforce in a massive way,” he said. “The fashion changed because they needed garments that allowed much more movement and freedom of expression and Lempicka really captured the essence of this new woman: liberated, sexually free, financially independent.”

But Lempicka is often not given her due, Rinaldi explained, with her impact simplified. “She’s been perceived — mostly by art historians — as a phenomenon of the Art Deco period… of the world of decoration and fashion,” he said. “But actually she was much more than that. She’s an incredibly gifted and outstanding painter, possibly one of the best of her generation.”

Lempicka was born at the end of the 19th century to a wealthy Polish family, though her exact place of birth is still unknown. She later settled in St. Petersburg, but was forced to flee the Russian Revolution and made her way to Paris in 1919. There, Lempicka blended a number of styles to make her own. Over her career, she took notes from the Russian avant-garde, the flat planes of cubism, the elegance of fashion illustration and advertising, and the composition and form of the Italian Renaissance and French Neoclassical painters.

But she was an outlier of major art movements and wasn’t always taken seriously on account of her aristocratic background — she was bitingly nicknamed the “Baroness with a Brush” in print in 1941.

Today, it’s difficult to stage a large showing of Lempicka’s work, Rinaldi explained, since her paintings and drawings are mostly in private collections, rather than in museums, and can change hands repeatedly.

“That had a great impact on her critical appreciation, because she’s not represented in museums and she’s not really seen as part of the canon,” he said.

An air of mystery

In 2021, the de Young acquired a drawing by Lempicka — a study of a young girl with ringlets and arched eyebrows she composed in 1937. It made the institution the first in the country to purchase one of her works, Rinaldi said. But three years on, the de Young’s curators have organized a full show filled with rarely and never-before-seen works.

They have also uncovered new information about the enigmatic artist, who often concealed or exaggerated details about her life and had a penchant for communicating through dramatic press releases. Streisand, who penned an opening essay for the show catalog, described Lempicka as a woman who “moved easily through the highest echelons of society — a cool, glamorous blonde with an air of mystery who had lovers of both sexes.”

Rinaldi pointed to her savvy sense of self-promotion. “She made great use of the media of the time,” he said. “She lied about some things. She introduced her daughter as her younger sister — sometimes silly things, sometimes more serious things. But certainly it shows a woman who’s fully in control of her life and her identity, who’s crafting her own persona.”

Some of Lempicka’s exaggerations were meant to place her in key historical moments, such as her claim that she arrived in New York from Europe on the very day the stock market crashed in 1929, catapulting the country into the Great Depression (she had actually arrived several months earlier). But other misrepresentations were an armor of sorts, like her Polish Catholic identity, when evidence points to Moscow as her birthplace, and research has recently revealed her Jewish heritage.

“Her grandparents are buried in the Jewish cemetery in Warsaw, but her parents converted to Christianity and baptized their children,” Streisand wrote. “It was safer not to be Jewish, and Lempicka clearly understood that. She painted her only daughter, Kizette, in her First Communion dress and made sure she was identified as Catholic.”

New revelations

In the show “Tamara de Lempicka,” the curators reveal her birth name for the first time: Tamara Rosa Hurwitz. They also update her birth year to 1894, four to eleven years earlier than Lempicka claimed when she was alive, based on documentation found by the Polish historian Andrzej Slowicki. And there’s new works on display for the very first time, including the 1928 painting “Spring,” of two women, one appearing to whisper to the other as she cradles small white blooms.

The exhibition spans from early Russian folkloric-influenced compositions in the 1920s; to the sultry nudes and modern, aristocratic portraits that became her calling card; to the quieter tabletop scenes she began painting during World War II. It includes the first painting that caught Streisand’s eye from a book cover the singer spotted in 1979: a self-portrait of Lempicka, her gaze fixed on the viewer as she drives a green Bugatti.

Lempicka received her first solo show in 1930 in Paris, and exhibited regularly around the city in the early years of her career. But that decade and the following, her style was “not aligned” with Surrealism or Abstract Expressionism, which prevailed as the dominant art movements, Rinaldi noted. “As maybe a defensive reaction, she really goes back to an extreme appreciation for the Old Masters, and she starts producing these religious scenes or very humble, simple still lives.”

The only group she fully embraced with was The Society of Modern Women Artists in Paris, which promoted equal representation of women in art and hosted an annual salon in which she participated throughout the 1930s. When she returned to the US just before war broke out in Europe in 1939, she exhibited at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Institute. Later, she and her second husband, Baron Kuffner, funded a traveling exhibition in New York, San Francisco and Milwaukee with the famed art dealer Julien Levy — eight of the twelve works from this original San Francisco stop hang in a recreated room in the de Young show.

In the 1940s, Lempicka’s work was the subject of a book for the first time, coinciding with an exhibition in Rome. But until the very last years of her life, when the Art Deco period had a scholarly resurgence, interest in her work remained thin and she considered her style “out of the fashion,” the de Young’s catalog notes.

Though Lempicka’s art is in fashion once again, and has enjoyed sustained interest for decades, Rinaldi says there’s still much scholarly and curatorial work to do to uncover her secrets.

“We’re really chipping just the surface of what can be done, what can be discovered about her,” he said.

Clarification: This story has been updated to include attribution of the discovery of the artist’s birth year.