In a harsh new world of climate disasters, Amber Henry clutched her four young children as they stood atop the oven in their home in Lakeland, Florida.

Transformers exploded outside. The surging floodwaters from Hurricane Milton poured in through the windows late Wednesday and their refrigerator slowly floated away.

“All I could do is pray and I had to be brave,” Henry told CNN the next day, saying she feared being electrocuted and leaving her children to fend for themselves.

“Mom, I don’t want to die for my birthday,” Henry recalled her daughter, who will soon be 11, telling her before the single mother summoned the will and strength to safely lead her children to a neighbor’s house on higher ground. The family’s home, around 35 miles east of Tampa, wasn’t even in an evacuation zone.

Broad swaths of the Sunshine State, in fact, are experiencing back-to-back jolts of anxiety, uncertainty and fear that experts say could have lasting effects.

Milton’s fury has already claimed at least 23 lives in Florida, delivering a lethal storm surge, torrential rains and dozens of tornadoes – compounding the suffering inflicted less than two weeks earlier by another “once in a lifetime” storm, Helene, which killed another 20 people as it barreled through the state.

Along with widespread death and destruction, two major hurricanes over a short period of time have left a vast trail of despair and frayed nerves that experts warn could make many Floridians more susceptible to depression and post-traumatic stress syndrome.

“It’s hard for me not to imagine the heartbreak,” Hillsborough County Sheriff Chad Chronister said Friday, becoming emotional as he surveyed flooding about 20 miles east of Tampa in the suburb of Valrico. Floodwaters from the Alafia River were six feet deep in some areas, lapping against the walls of homes.

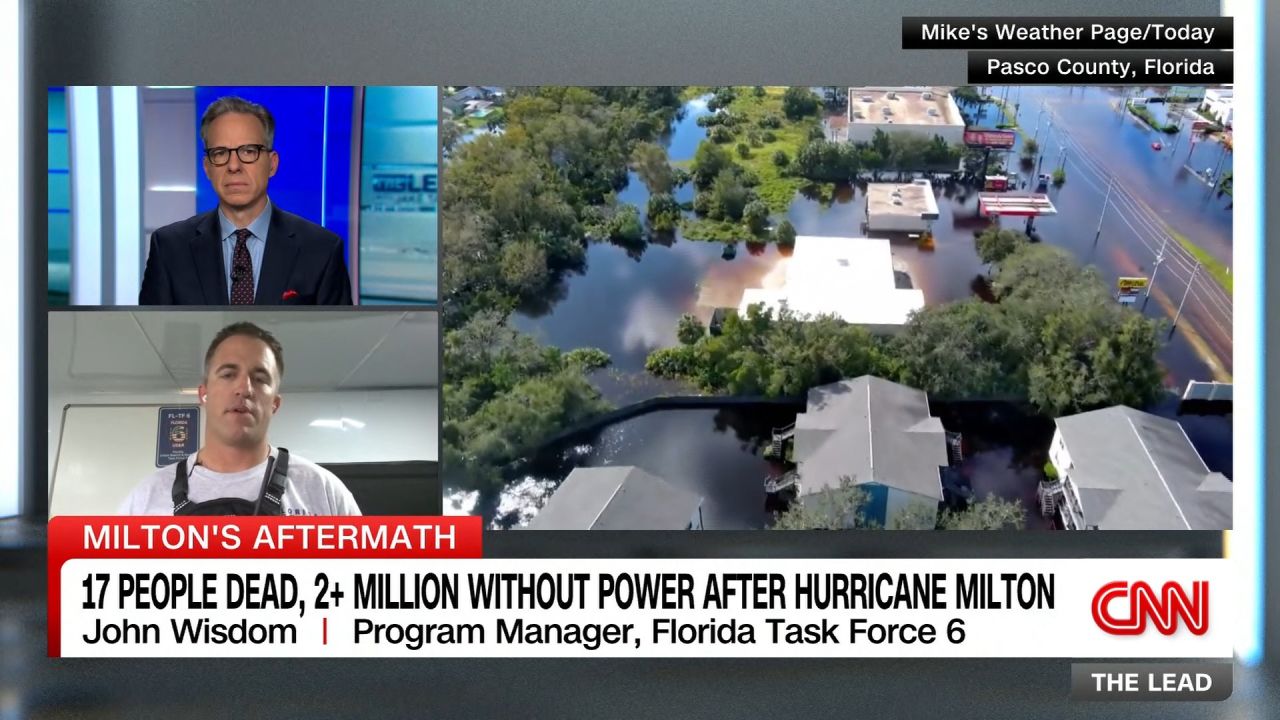

A flood warning was issued for the river in Lithia as it crossed major flood stage Thursday and exceeded more than 24 feet on Friday. In Hillsborough County alone, first responders have rescued more than 700 people since Milton made landfall on Wednesday night as a Category 3 storm near Siesta Key, on Florida’s west coast, with 120 mph sustained winds.

“Where do those people go that don’t have family? They don’t have friends. They don’t have the money to get a hotel. What happens to them?” Chronister asked of locals still losing homes days after Milton made landfall.

Even after floodwaters subside, the stress and anxiety can lead to lingering mental health challenges.

Florida residents who lived through Hurricanes Irma and Michael in 2017 and 2018 were more likely to experience compounded mental health issues, according to one 2022 study. Hurricanes and flooding generate anxiety, depression and stress. Storms can exacerbate existing mental health problems or lead to new ones. And the biggest health concern from a flood may be mental, studies have shown.

“What we’re seeing now is much more intense in terms of that repeated exposure,” said Dana Rose Garfin, a psychologist and professor of public health at UCLA who co-authored the 2022 study.

“There’s the psychological aspect of not really having time to recover and prepare before you’re on to the next crisis,” Garfin said. “But in this case, there was the physical inability to recover from the disaster before the next one hit. People were still clearing the debris.”

‘Your heart shatters for these people’

More than a million utility customers in Florida were still without power this weekend, according to PowerOutage.us. The highest numbers of outages were in areas where Milton made landfall, including Pinellas, Hillsborough, Manatee and Sarasota counties.

Milton brought the ocean’s fury ashore with several feet of storm surge, three months’ worth of rain in three hours in some areas and a deadly tornado outbreak as it churned from the Gulf to the Atlantic. The hurricane tore apart homes, toppled trees, tossed boats and trucks like toys, inundated roads and shredded the roof of Major League Baseball’s Tropicana Field in downtown St. Petersburg as it was being prepared to serve as a shelter for first responders, who have rescued more than a thousand flood victims so far.

On Thursday, Hillsborough County sheriff’s deputies rescued about 135 elderly people, many using wheelchairs or walkers to get around, who were trapped in waist-deep water at a Tampa assisted-living facility where many had been taken to from an evacuation zone.

“They were evacuated from Bradenton to stay safe,” Chronister, who has been with the sheriff’s office for more than three decades, told CNN, his voice choking with emotion. “This is a neighborhood that doesn’t have a lot.”

Water came up to four feet into first floors of buildings in the largely Latino community, he said. Their church, their cars and more were gone.

“They have very little … and they’ve lost everything,” Chronister said. “These are people that live day to day and they have nothing … Your heart shatters for these people.”

As they waited to be loaded onto a school bus, some residents in wheelchairs, still shivering, described sitting overnight with their feet in the cold floodwaters that poured in through windows and air conditioning vents.

Concerns about the mental health effects of back-to-back disasters come as researchers predict more frequent extreme weather events.

Research published last year in the journal Nature Climate Change found rising sea levels and climate-driven hazards could make destructive back-to-back hurricanes more common, particularly in areas such as the Gulf Coast.

“When we talk about a new era, we have to recognize these kinds of possibilities,” said Ning Lin, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Princeton University and co-author of the research paper.

“Before we were thinking about how do we deal with one event,” she said. “People have not really thought about how to deal with such kinds of events back to back.”

Back-to-back disasters make recovery harder

On Wednesday, as Milton made landfall, Sara Lesker managed to ride out the storm in her home in St. Petersburg, where she moved two months ago from Long Island in New York. She hunkered down with her 15-month-old daughter, who watched one of the Trolls movies during the night, and their two cats.

“The weather here is different,” she told CNN. “We expected storms and sunshine, but I don’t think we expected like two hurricanes in less than 10 days.”

About 60 miles east that same night, in Lakeland, a WFLA TV news crew eventually rescued Henry and her children after they were trapped in a flooded house for seven hours.

They are now homeless; the family car underwater, she said.

“I have nothing. Me and my children didn’t even have shoes. The only thing we have is wet clothes on (our) backs,” Henry said. Social security cards, birth certificates and other vital documents are gone.

She took video that night that showed floodwaters rising in the home.

“I pray to God, come help us. God, help us. This water is so tall. It’s going up the cabinets,” Henry said in the video.

From the neighbor’s home, Henry said, she spotted a person up the road and called out for help before the news crew rescued them.

“It felt like a movie, the worst nightmare and I’m so glad I’m able to actually talk about it right now,” Henry said.

The full scope of the emotional toll from Florida’s back-to-back disasters will not be known for some time, said psychoanalyst Dr. Gail Saltz, a clinical professor of psychiatry at New York Presbyterian Hospital. But research suggests the hurricanes will make people more vulnerable to mental health problems and likely make it harder for them to recover, she said.

“That is what we’re seeing in Florida right now,” she added.

In Bartow, Florida, Kayla Lane, her brother and mother were awakened early Thursday after Milton’s howling winds knocked a tree through the roof of their home. Insulation and other debris rained down on the living room couch where they had been sitting less than an hour earlier.

“It’s a home for squirrels,” Lane said of what remained of the family house 40 miles east of Tampa.

Staying at a hotel for now, Lane said, her family is “Fine, physically. Emotionally, maybe not.”

CNN’s Isabel Rosales, Ashley R. Williams, Christina Zdanowicz, Amanda Jackson, Emma Tucker, Cindy Von Quednow, Cheri Mossburg, Chelsea Bailey, Caroll Alvarado, Rebekah Riess, Devon Sayers, Mary Gilbert, Andy Rose, Zoe Scottie, Taylor Romine and Paradise Afshar contributed to this report.