A pair of blood-spattered trousers in a miso tank and an allegedly forced confession helped send Iwao Hakamata to death row in the 1960s.

Now, more than five decades later, the world’s longest-serving death row prisoner has had his name cleared, according to public broadcaster NHK.

A Japanese court on Thursday acquitted 88-year-old Hakamata, who was wrongfully sentenced to death in 1968 for murdering a family, marking the end of a marathon legal saga that’s brought global scrutiny to Japan’s criminal justice system and fueled calls to abolish the death penalty in the country.

Judge Kunii Tsuneishi of the Shizuoka District Court ruled the blood stained clothing which was used to convict Hakamata was planted long after the murders, NHK reported.

“The court cannot accept the fact that the blood stain would remain reddish if it had been soaked in miso for more than a year. The bloodstains were processed and hidden in the tank by the investigating authorities after a considerable period of time since the incident,” Tsuneishi said.

“Mr. Hakamata cannot be considered the criminal.”

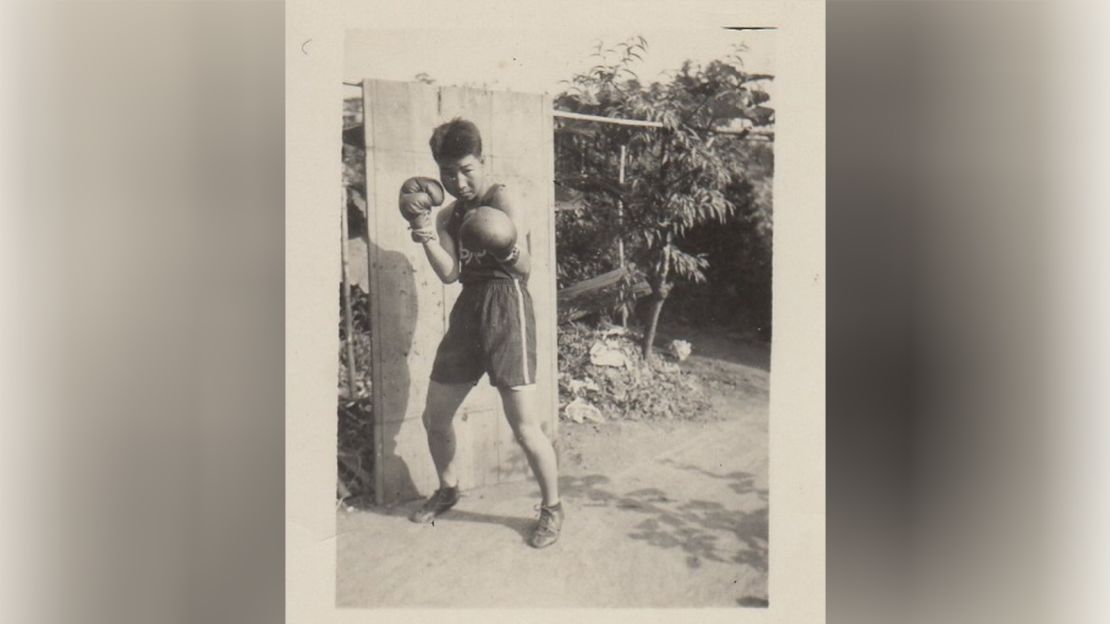

Once a professional boxer, Hakamata retired in 1961 and got a job at a soybean processing plant in Shizuoka, central Japan – a choice that would mar the rest of his life.

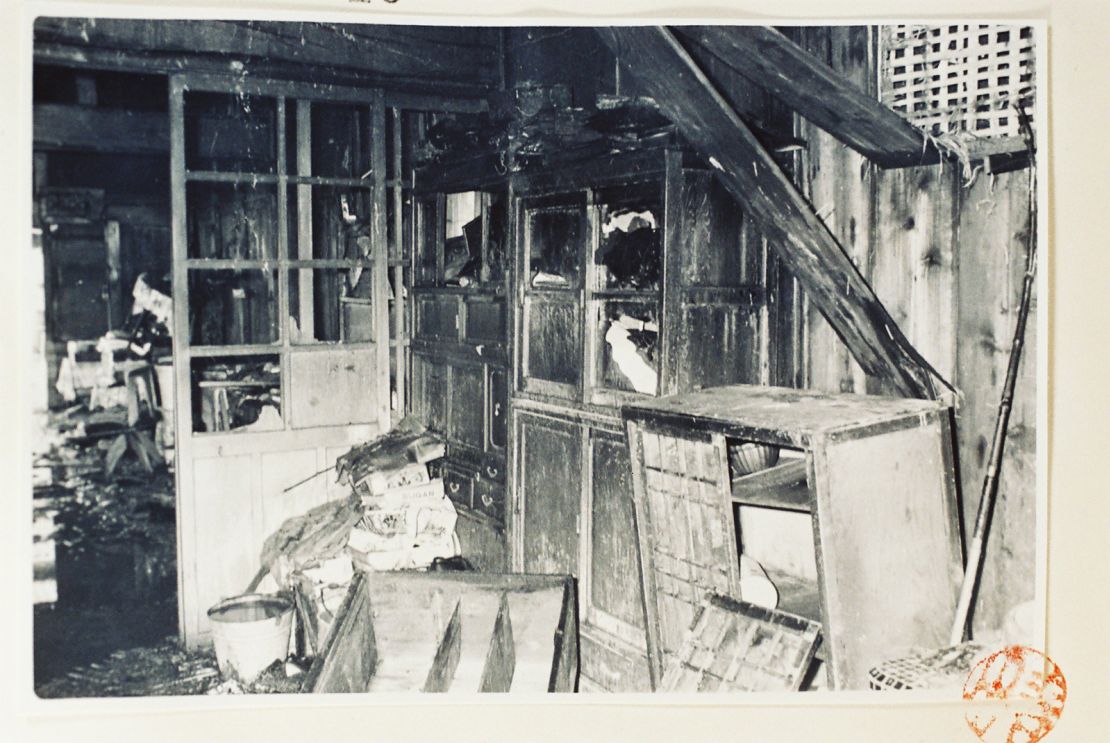

When Hakamata’s boss, his boss’s wife, and their two children were found stabbed to death in their home in June five years later, Hakamata, then a divorcée who also worked at a bar, became the police’s prime suspect.

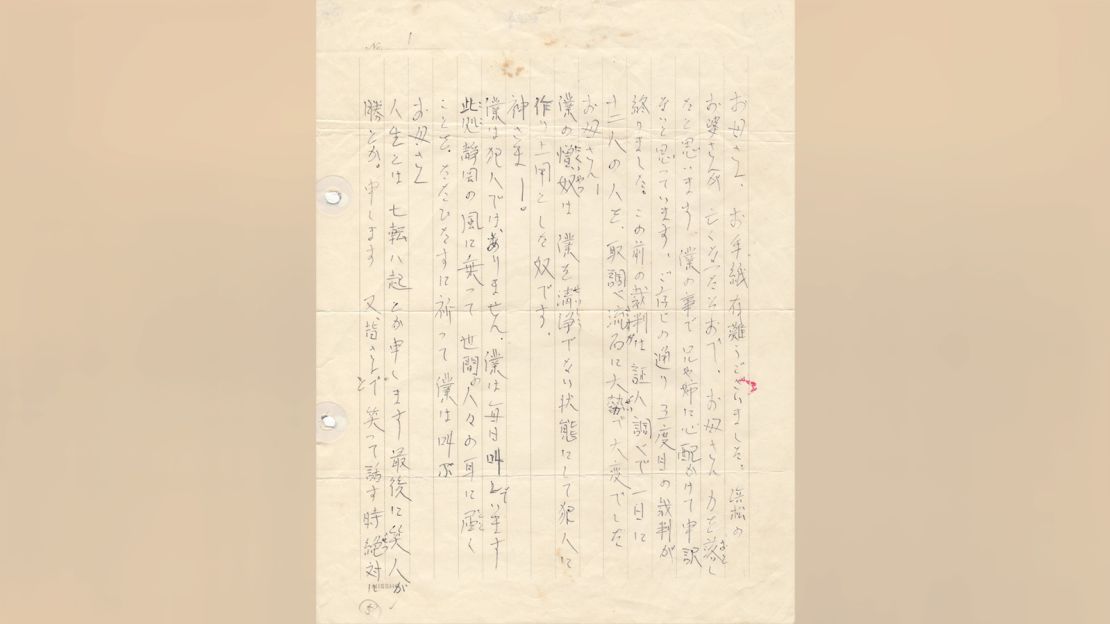

After days of relentless questioning, Hakamata initially admitted to the charges against him, but later changed his plea, arguing police had forced him to confess by beating and threatening him.

He was sentenced to death in a 2-1 decision by judges, despite repeatedly alleging that the police had fabricated evidence. The one dissenting judge stepped down from the bar six months later, demoralized by his inability to stop the sentencing.

Hakamata, who has maintained his innocence ever since, would go on to spend more than half his life waiting to be hanged before new evidence led to his release a decade ago.

After a DNA test on blood found on the trousers revealed no match to Hakamata or the victims, the Shizuoka District Court ordered a retrial in 2014. Because of his age and fragile mental state, Hakamata was released as he awaited his day in court.

The Tokyo High Court initially scrapped the request for a retrial for unknown reasons, but in 2023 agreed to grant Hakamata a second chance on an order from Japan’s Supreme Court.

Retrials are rare in Japan, where 99% of cases result in convictions, according to the Ministry of Justice website.

A justice system under scrutiny

Hideko, Hakamata’s 91-year-old sister said she “couldn’t stop crying and tears were overflowing” when she heard the verdict.

“When the judge said the defendant was not guilty, it sounded divine to me,” said Hideko, who has campaigned for Hakamata’s innocence for more than half of her life.

Hideyo Ogawa, Hakamata’s lawyer, called the ruling “groundbreaking,” adding “58 years was too long.”

Even as his supporters cheered Hakamata’s acquittal, the good news will not likely register with the man himself.

After decades of imprisonment, Hakamata’s mental health has declined and he’s “living in his own world,” said Hideko, who has long campaigned for his innocence.

Hakamata seldom speaks and shows no interest in other people, Hideko told CNN.

“Sometimes he smiles happily, but that’s when he’s in his delusion,” Hideko said. “We have not even discussed the trial with Iwao because of his inability to recognize reality.”

But Hakamata’s case has always been about more than one man.

It has raised questions about Japan’s reliance on confessions to get convictions. And some say it’s one of the reasons why the country should do away with the death penalty.

“I’m against the death penalty,” Hideko said. “Convicts are also human beings.”

Japan is the only G7 country outside of the United States to retain capital punishment, though it did not perform any executions in 2023, according to the Death Penalty Information Center.

Hiroshi Ichikawa, a former prosecutor who was not involved in Hakamata’s case, said historically Japanese prosecutors have been encouraged to get confessions before looking for supporting evidence, even if it means threatening or manipulating defendants to get them to admit guilt.

An emphasis on confessions is what allows Japan to maintain such a high conviction rate, Ichikawa said, in a country where an acquittal can severely hurt a prosecutor’s career.

A long fight for exoneration

For 46 years, Hakamata was held behind bars after being convicted on the basis of the stained clothing and his confession, which he and his lawyers say was given under duress.

Ogawa, Hakamata’s lawyer, told CNN that Hakamata was physically restrained and interrogated for more than 12 hours a day for 23 days, without the presence of a defense attorney.

“The Japanese judicial system, especially at that time, was a system that allowed investigative agencies to take advantage of their surreptitious nature to commit illegal or investigative crimes,” Ogawa said.

Chiara Sangiorgio, Death Penalty Advisor at Amnesty International, said Hakamata’s case is “emblematic of the many issues with the criminal justice (system) in Japan.”

Death row prisoners in Japan are typically detained in solitary confinement with limited contact with the outside world, Sangiorgio said.

Executions are “shrouded in secrecy” with little to no warning, and families and lawyers are usually notified only after the execution has taken place.

Hakamata has spent most of his life behind bars for a crime he did not commit.

However, despite his poor mental health, over the past decade, Hakamata has gotten to enjoy some of the small pleasures that come with living freely.

In February, he adopted two cats. “Iwao began to pay attention to the cats, worry about them, and take care of them, which was a big change,” Hideko said.

After handing down the verdict, the judge, clearly emotional, apologized to Hideko, NHK reported.

“The court is very sorry that it has taken so long.”

Hideko wiped her tears with a handkerchief.

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect that Hakamata was acquitted and exonerated by the court, not declared innocent.

CNN’s Nodoka Katsura contributed to this report.