Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

For years, Egyptologists have hotly debated how the massive pyramids of ancient Egypt were built more than 4,000 years ago. Now, a team of engineers and geologists brings a new theory to the table — a hydraulic lift device that would have floated the heavy stones up through the middle of Egypt’s oldest pyramid using stored water.

Ancient Egyptians built the Step Pyramid for Pharaoh Djoser in the 27th century BC, and it was the tallest structure at the time, coming in at about 62 meters (204 feet) tall. But how exactly the monument was erected, with a number of stones weighing in at 300 kilograms (about 661 pounds), has remained a centuries-old mystery, according to the study published Monday in the journal PLOS One.

“Many detailed publications have discussed pyramid-building procedures and provided tangible elements, but these usually focus on more recent, better-documented, and smaller pyramids of the Middle and New Kingdoms (1980 to 1075 BC),” said lead author Dr. Xavier Landreau, CEO of Paleotechnic, a privately owned research institute in Paris that studies ancient technologies.

“The techniques involved could include ramps, cranes, winches, toggle lifts, hoists, pivots, or a combination of these methods,” he added in an email. “But what about the Old Kingdom pyramids (2675 to 2130 BC), which are much bigger? While human strength and ramps may be the sole construction force for small structures, other techniques may have been used for large pyramids.”

Using an interdisciplinary approach, the new paper was the first to report a system consistent with the Step Pyramid’s internal architecture, the authors wrote.

A complex water treatment system drawing upon local resources would have allowed for a water-powered elevator within the pyramid’s internal vertical shaft. Some type of float would have raised the heavy stones up the middle of the pyramid, according to the study.

While the theory is an “ingenious solution,” some Egyptologists aren’t convinced, as a more widely believed theory is that the ancient Egyptians used ramps and haulage devices to put the heavy blocks in place, said Egyptologist Dr. David Jeffreys, a retired senior lecturer in Egyptian archaeology at the University College London who was not involved with the study. Here’s what experts have to say on the new theory.

Egypt’s desert was once savannah

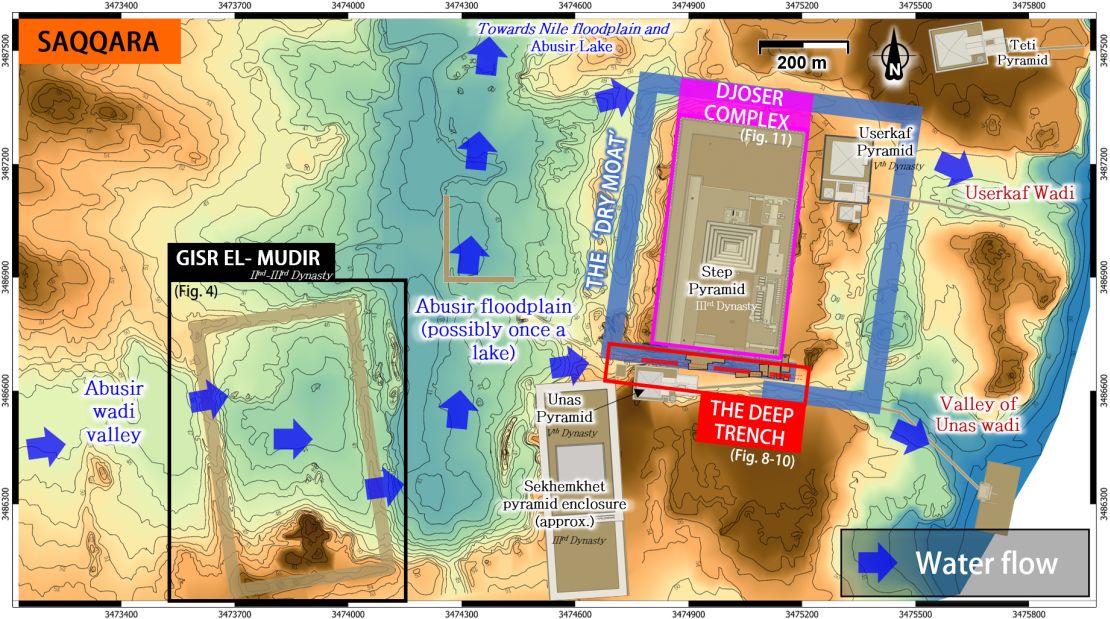

By analyzing available data, including paleoclimatology, the study of ancient climates and archaeological data, the study team suggested that water from ancient streams flowed from the west of the Saqqâra plateau into a system of deep-water trenches and tunnels that surrounded the Step Pyramid.

The water also would have flowed into the Gisr el-Mudir — a rectangular limestone structure that is a massive 650 by 350 meters (2,133 feet by 1,148 feet) — which would have acted as a check dam. This device, which was previously thought to be a fortress, a celebration arena or a cattle enclosure, would control and store water from heavy floods, as well as filter out sediment and dirt so they would not clog the water passageways.

The theorized water treatment system would not only allow for water control during flood events, but also would have “ensured adequate water quality and quantity for both consumption and irrigation purposes and for transportation or construction,” said study coauthor Dr. Guillaume Piton, a researcher with France’s National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment, or INRAE, based at the Institute of Environmental Geosciences of the University Grenoble Alpes.

The authors pointed to several prior studies that found the Sahara Desert saw more regular rainfall thousands of years ago than it does today. The landscape would instead have resembled a savannah, which could support more plant life than arid desert conditions. However, there is debate on when exactly the climate conditions were wetter.

There might have been enough water to support a system such as the hydraulic lift, said Dr. Judith Bunbury, a geoarchaeologist at the University of Cambridge in London who was not involved with the new study. She pointed to past research that found rainwater gutters being built and used in the Old Kingdom, as well as past research thatlooked at the diet of birds during the time, which had consisted of wetland species such as frogs.

“I think there’s fairly widespread belief that it was rainier in the Old Kingdom, certainly the early Old Kingdom when the Step Pyramid was being built,” she added.

On the other hand, experts debate whether there would have been enough constant rainfall to fill up the structures that would have supported the hydraulic lift, such as the “Dry Moat,” a giant channel that surrounds the Step Pyramid and nearby structures, that the authors believe collected water that helped power the elevator when in use.

The Sahara’s greener period most likely ended by the beginning of the third millennium BC, according to Jeffreys. The low rainfall would not be able to fill the structures to the extent needed for a hydraulic lift, and furthermore would not be able to keep up with the water loss within the structure’s limestone, added Dr. Fabian Welc, director of the Institute of Archaeology at the Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University in Warsaw, Poland. Welc was not involved with the new study.

“There was a wetting of the climate (seasonal — winter rains) in northern Egypt (also in Saqqāra) during the 3rd Dynasty (2670-2613 BC), but their intensity was relatively low. These rains, even filling the wadis (a dry valley except in rainy seasons) with water, would not have been able to fill the dry moat even to a small extent … these waters would have been immediately drained by gravity deep into the rock massif, about which there is no doubt (unless it was a biblical flood),” Welc said in an email.

The study authors agreed that it’s very unlikely that the system was filled with water permanently and argue it’s more probable that flash floods of the time could have supplied enough water to support the hydraulic lift during construction of the pyramid. However, there is still more research needed to know exactly how much rainfall and flooding likely occurred during this time, the authors noted in the study.

This is not the first time the Nile has been investigated as to whether it played a role in the building of the pyramids. A study published in May found a dried-up branch of the massive river and theorized that the stream was likely used to transport massive limestone blocks to construction sites of multiple pyramids. There is also some evidence of ancient Egyptians using hydraulics on a smaller scale, Jeffreys said.

Mysteries of ancient Egyptian structures

Researchers previously have not determined a clear purpose for the vertical shaft within the pyramid of Djoser. Some later pyramids, such as the Great Pyramid of Giza, have shafts believed to have been used for ventilation, and it’s possible the internal shaft could have also been intended for lighting or to relieve pressure on the chamber beneath, Jeffreys said. But as the first of its kind, the Step Pyramid was an experimental structure that is believed to have started out as a mastaba (a flat tomb) and was built up, so it remains unclear exactly what its internal features were intended for, he added.

The shaft within the Step Pyramid is connected to a 200-meter-long (656-foot-long) underground tunnel that connects to another vertical shaft outside the pyramid. The external shaft might then connect to a hypothesized water transportation section of the Dry Moat, referred to as the Deep Trench, but further research is needed, the authors wrote in the study.

The internal shaft begins directly below the pyramid near the center where a granite box sits with a plug at its base. This box is more widely believed to be the burial chamber of King Djoser, but instead, the authors suggest it was built for the purpose of opening and closing the hydraulic lift, allowing the water to fill the shaft when in use.

As for whether other pyramids were built using this method, Landreau said that further investigation is needed. “It may hold the key to uncovering the mystery of how the largest monoliths, found in pyramids like Khufu or (Khephren) were raised. These monoliths weigh tens of tons, making it seemingly impossible for them to be hauled using (human labor) alone. Conversely, a moderate-sized hydraulic lift can raise 50 to 100 tons. Exploring concealed shafts within these pyramids could be a promising avenue for research,” he added.

Despite the over 4,000-year-old mysteries that surround the pyramids and features, there is sufficient documentation that the ancient Egyptians used certain technologies such as scaffolding and mud-brick ramps to assist in the construction of varying structures, said University of Cambridge geoarchaeologist Bunbury, whereas there is no documentation or depictions of a water-powered lifting device to her knowledge.

“I think people, even since antiquity, have been inspired by the pyramids as a massive building project,” Bunbury said. “And they find it quite difficult to believe that they were just built by ordinary people at that time, partly because they see it as a long time ago. … It’s puzzling that there are so many proposals of what might be technological sort of innovation that was then dropped again, when we know they had technical solutions to these things anyway.

“It doesn’t mean (the hydraulic lift device) wasn’t used,” she added. “But there’s a sort of Occam’s razor of what’s the simplest thing based on what we already know.”