A version of this story appeared in CNN’s What Matters newsletter. To get it in your inbox, sign up for free here.

It’s a story — young memoirist with an Ivy League law degree tells a compelling story, catapults into the Senate and joins the national political conversation — familiar to anyone who followed the career of Barack Obama.

But instead of Obama, the memoirist of the moment is JD Vance, the Republican senator from Ohio, who has been tapped by former President Donald Trump as his vice presidential running mate and, at 39, the next generation of the MAGA movement.

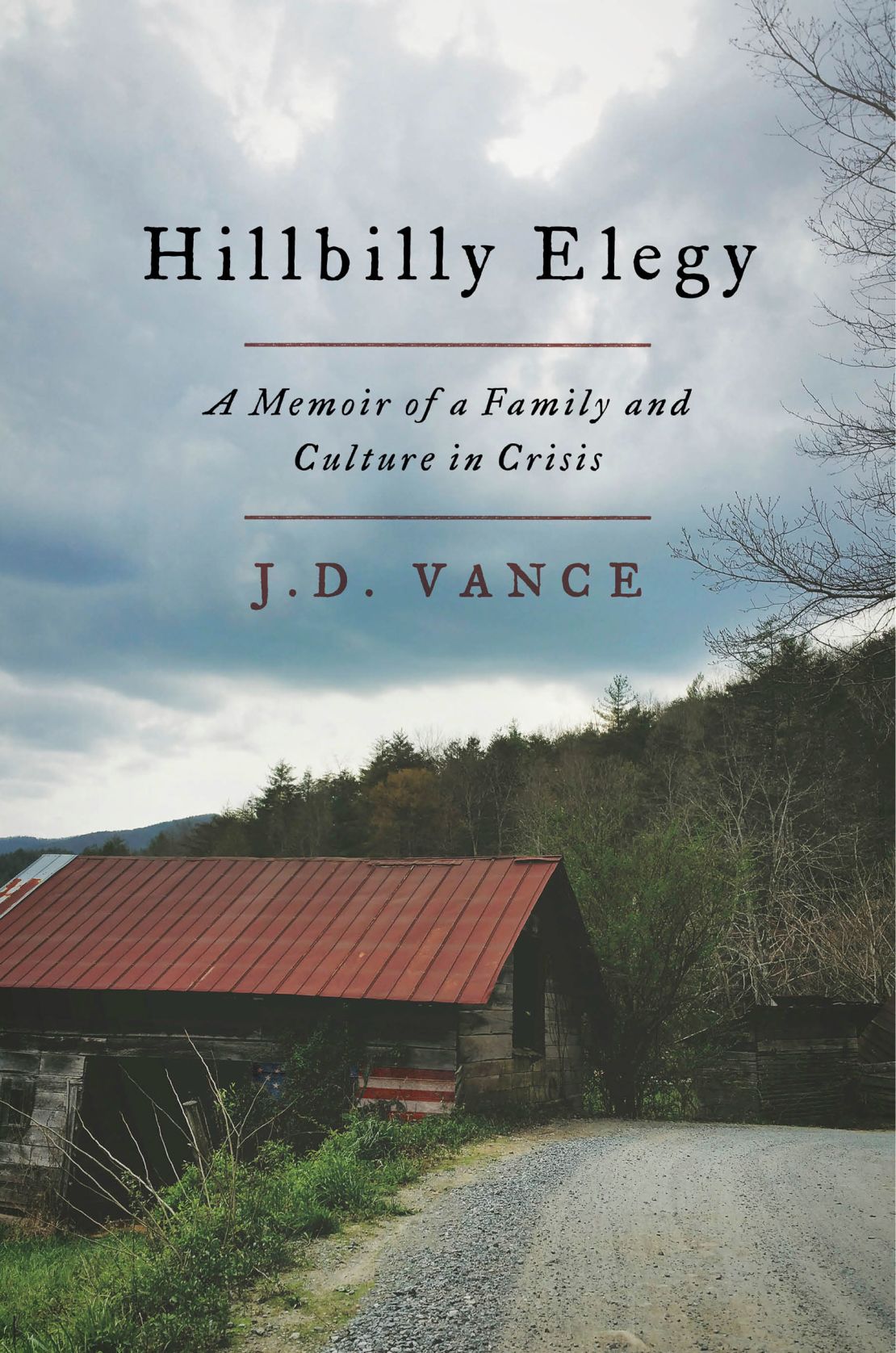

Vance’s book, like Obama’s, is about a young man largely raised by his grandparents and overcoming themes of alienation. Vance’s“Hillbilly Elegy” was also turned into a Ron Howard movie.

“Hillbilly Elegy” caused a sensation after Trump’s election in 2016 as people tried to understand how Democrat Hillary Clinton had lost the Rust Belt states. The book, with touching stories about Vance’s upbringing, his drug-addicted mother and his foul-mouthed, gun-toting grandmother, attempts to explain the disaffection of the white, working-class Americans who felt like American society was passing them by as they witnessed the decay of once-thriving towns.

Vance has clearly evolved since the book’s publication. He opposed Trump when it was first published just before the 2016 election and is now on the same presidential ticket, a full-fledged Trump acolyte.

Trump’s and Vance’s stories are about as opposite as it is possible for the stories of two white men to be.

Trump built his business career with loans from his father. Vance dropped his biological father’s name, Donald, to simply become JD.

Trump was born into wealth in a city where he lived most of his life. Vance counts his home as Kentucky, where his grandparents were from and where he visited as a child.

Trump avoided service in Vietnam. Vance enlisted in the Marines and deployed to Iraq.

Where Trump has an “I alone can fix it” view of the world, Vance takes a far more humble approach to his own abilities and credits others with helping him succeed despite despair in his home town.

Here are some quotes from the book that struck me on a rereading:

Vance’s grandparents didn’t graduate from high school and they moved, he says, from Kentucky to Ohio when his grandmother was pregnant at the age of 14, in search of work and a better life. His grandfather made a life as a steelworker and, despite his mother’s descent into addiction, his grandparents were among “a handful of loving people (who) rescued me.”

He feels kinship with people whose families, like his, have roots in Appalachia and have not kept pace with social mobility in the US.

There are multiple passages about how views in these communities about how a man should act are hurting men, who, he says, drop out of the labor force and refuse to relocated for opportunity.

While Vance acknowledges that his Mamaw only survived in her later years with government help, there is a marked disdain for programs that help people who are not old. Vance says:

Much of the book is built around Vance’s relationship with his grandmother, Mamaw, “the toughest woman anyone knew,” who died in 2005 and who he lovingly mentioned in his speech Wednesday at the Republican National Convention. The book is filled with foul-mouthed quotes and gun-toting anecdotes about her and other members of his Kentucky forebears.

At a time when immigration plays such an important role in national politics, it’s interesting that migration within the US is a key component of Vance’s book. His family and millions of others like them had to move to make their way in the world.

His grandparents were Democrats because of social class.

He argues that the American Dream felt attainable to his grandparents’ generation.

The book is specifically about white, working-class Americans. But at several points Vance compares the plight of white Americans in Appalachia and in the Rust Belt to that of Black Americans left behind in American cities.

Vance takes a dim view of people who complain about lack of work in their towns. He says many of them are lazy.

Now a practicing Catholic, he is frustrated that more people in the Rust Belt do not attend church and he repeatedly argues that churches can provide support to people who are in need.

In one key section describing a job during his teenage years at a grocery store in roughly the early 2000s, Vance expresses anger at people getting help from the government, but able to have phones, which were not as ubiquitous back then.

It was seeing people “live off the dole,” that began to turn Vance against Democrats, although I have to say that reading this passage today I’m not sure how many people getting food assistance are buying T-bone steaks.

A general move away from Democrats in the Rust Belt could be explained through a racial lens, by the Democrats’ embrace of the Civil Rights movement, or for social reasons, as evangelical Christians gravitated to the right. But Vance says an aggrieved perception of welfare programs is largely to blame. He also tells the story of his grandmother’s frustration when a neighbor rents out his house as a Section 8 property. Conversely, Mamaw would also bristle that ballots to raise taxes for local schools would fail.

Eventually, Middletown, Ohio, began to founder much as the Kentucky of Mamaw’s youth.

Vance sees a general societal decline in these areas and it’s about more than a lack of jobs.

Vance prizes hard work and thoughtful financial decisions. He joins the Marines specifically in order to afford college, so it should be no surprise that today he is a vehement critic of student loan forgiveness.

There is also a passage where, as an Ohio State student, he describes making use of a payday loan. He argued that while these loans might have exorbitant interest rates and appear rapacious to consumer advocates, the loan was there when he needed it. So he opposed a bill then under consideration in Ohio to regulate payday loans.

As Vance headed off to Yale Law School, his future bright after years of work, he began to feel out of place in Middletown, where despair was growing.

There are the beginnings of a desire for a populist hero.

Vance does not see racism in the rejection by many White Rust Belt viewers of Obama, but rather anti-elitism.

He also sees a failing on the right to promote accountability and inspire people to succeed.

Vance feels out of place in Middletown, but also at Yale. He also becomes more health-conscious during the course of the book.

At one point, Vance meets a politician from Indiana.

One can imagine Daniels, a former Indiana governor and George W. Bush official who is opposed by the MAGA wing of the GOP, is no longer Vance’s hero.

The short final chapter that suggests social policy needs to do more to understand the white working class, but it’s not particularly detailed. Vance points out that his rise was built on government help, including student loans, the old age benefits his grandmother shared with him and the public schools of his youth and college years. He argues that the country should do more to integrate low-income people into the middle class. The closest he comes to a policy proposal is frustration at how the federal government applies Section 8 housing assistance. Later, he admits that answers are hard to come by.