It was 2022 and Florida Sen. Marco Rubio had just finished debating his Democratic opponent Val Demings when former President Donald Trump was on the line.

According to a source familiar with the conversation, Trump was calling to relish in Rubio’s performance, telling the Republican senator that he’d done well and offering to do whatever he needed in the closing days of his campaign to make sure Rubio went back to Capitol Hill.

Weeks later, Trump appeared at a massive rally in Miami, telling the audience, “You need Marco Rubio fighting for you in the US Senate. He is fantastic.”

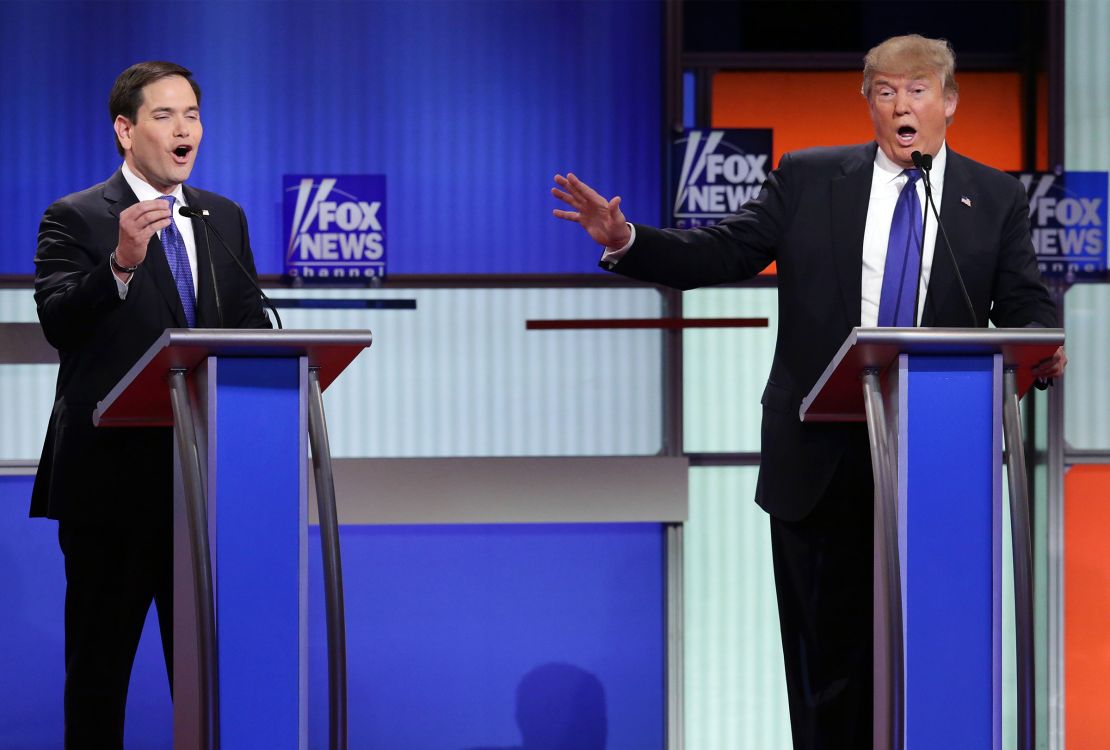

It was a remarkable shift for two men who just six years earlier had been bitterly entrenched in a primary battle for the White House, but also reflects Rubio’s ultimate embrace of Trump, whom he learned to work with closely in his presidency.

For Rubio, the last eight years have been an education.

In failure. In humility. In navigating a Republican Party overtaken by Trump and a job he was once desperate to leave. The story of Rubio’s transformation is not entirely unique for a member of Congress or even a one time foe, but reflects the political reality that surviving in the party at odds with Trump is no longer an option for members who want a future beyond him.

And now, as he finds himself on the shortlist of candidates who could be selected as Trump’s running mate, Rubio’s evolution is both a liability and perhaps his greatest asset.

The Florida senator, who nearly left the body after he was defeated in the GOP presidential primary in 2016, has spent the last eight years rebuilding his image in the likeness of a populist in Washington. At the same time, he has sharpened his foreign policy credentials as the leading Republican on the Senate Intelligence Committee, while building relationships in his party, across the aisle and around the globe.

In interviews with lawmakers, aides and GOP strategists, many see Rubio as a clear messenger and a figure who could be a reliable conduit to the White House, a key negotiating partner, and in the eyes of Republicans, maybe even a steadying force for Trump if he returns to the West Wing next year.

But Rubio, 53, is hardly the same politician whom Time magazine once dubbed “The Republican Savor” on its cover, nor the person who pitched himself to GOP voters in 2016 as the son of Cuban immigrants and a living demonstration that the American dream was alive and well. Rubio now defends his change, saying the 2016 campaign was an education and one that changed his outlook and approach to politics. Trump was part of it. But Rubio argues that isn’t the whole story.

“I got to go to places I’d never been and meet people I’d never interacted with and realized there’s millions of millions of Americans out there for whom the American dream I believed in and was so enthusiastic about, a lot of them thought it was increasingly out of reach. They’d lost their jobs because they got sent to China. They lived in a town where everywhere some shuttered factory or boarded-up Main Street shop reminded them of a once vibrant town that was hollowed out,” Rubio told CNN in an interview.

“You know in time, you grow to appreciate how Trump gave voice to that sentiment that needed to be heard and that needed to transform our party,” he added.

Still, some former supporters who once saw great promise in Rubio as part of a new generation of Republicans now view him as an example of a GOP that has lost its way.

“He’s made a 180-degree transition from being a center-right Republican with certain issues he championed like immigration, to becoming a total Donald Trump follower,” said Al Cardenas, a former Florida Republican Party chairman and one time mentor to Rubio. “He’s not the only one who made the transition.”

From ‘Republican savior’ to Trump convert

The Rubio of today looks very different from the freshman senator plotting his way to the White House more than a decade ago.

Back then, Rubio was in his early 40s and already viewed in Florida as an ambitious climber.

At age 28, he jumped at the chance to run for Florida’s House of Representatives, leaving behind the West Miami City Council seat he was just sworn into the year prior. He steadily rose up the party leadership in Tallahassee, eventually becoming speaker of the House.

Termed out of his seat in 2010, he decided to run for US Senate, pitting himself against his party’s own governor, Charlie Crist. By capturing tea party fervor, Rubio eventually pushed Crist to run as an independent and emerged victorious in the three-way race.

“If you look at his political climb, it’s an impressive climb,” said Cardenas, who once employed Rubio at his law firm. “He came from being a humble kid, who graduated from law school and barely eked out a victory in a small municipal race. Now he’s a US senator for one of the three biggest states in the country. Anyone looking at it from the outside would say that’s a very impressive rise.”

The establishment and GOP donors were reckoning with how to become a more inclusive, big tent party, with immigration reform seen by many – including a young Rubio – as a way to make inroads with Latino voters who had voted in droves for President Barack Obama over Republican Mitt Romney.

Rubio took the opportunity in stride, helping negotiate a massive, bipartisan immigration bill that would have invested more than $40 billion in border security and legalized millions of immigrants living in the US unlawfully at the time.

The bill passed the Senate, but then stalled out in the House. Rubio distanced himself from it. Then, as Trump emerged on the scene, the trajectory of the party and Rubio’s own path began to shift.

“Clearly he has evolved along with the rest of the party on issues like immigration and is far more populist,” one former Rubio aide told CNN. “But, I think he would argue the facts on the ground have changed too.”

When Rubio declared his candidacy for president – even as his friend former Gov. Jeb Bush was laying the groundwork for a run of his own – the then-junior senator from Florida announced his decision first on a call with donors before a rally in MIami.

“My candidacy might seem improbable to some watching from abroad,” Rubio said when he announced his candidacy. “In many countries, the highest office in the land is reserved for the rich and powerful. But I live in an exceptional country … where even the son of a bartender and a maid can have the same dreams and the same future as those who come from power and privilege.”

But in the closing days of his campaign, Rubio spared no schoolyard attack on Trump, saying he wasn’t going to “make America great. He’s gonna make America orange,” mocking the size of Trump’s hands and calling him a “con artist” vying to take over the Republican Party. In his concession speech in 2016, Rubio appeared to grapple in real time with what had become apparent in the primary: Voters weren’t interested in expanding the tent of the GOP with a hopeful message, they were attracted to Trump’s bluster and his populist message.

“People are angry. They are frustrated and left behind by this economy and then they are told, ‘Look, if you are against illegal immigration, that makes you a bigot,’” Rubio said. “Quite frankly there are millions people in this country that are tired of being looked down upon.”

And in the intervening years since, Rubio and Trump’s relationship has not only thawed, it’s flourished.

“I didn’t know him before he ran. I got to work with him and grew to respect the way he functioned as president, but when he first ran I didn’t know anything about him other than I knew he was famous and well known, but I didn’t know him as a person,” Rubio said.

Asked how he could go from being the butt of Trump’s attacks in 2016 to being as close as he is with Trump today, Rubio fired back, “that was a campaign.”

“That is like asking a boxer why they punched somebody in the face in the third round. It’s because they were boxing. Doesn’t mean you hate the guy, but we were in a competition for the same job,” he said. “Maybe other people are different, but if he was a Democrat and we had a tough campaign wouldn’t everybody be insisting we come back and work together, right? So why not expect that and then some when it’s a Republican?”

Mike Fasano, a former state House majority leader in Florida, said he’s unsurprised by Rubio’s political shift.

Fasano named Rubio to his leadership team soon after he arrived in Tallahassee, hoping the “shining star of the Republican Party” would also help carry the banner of Ronald Reagan conservativism to a new generation of voters. Instead, Fasano said, “I found out soon after that he went where the wind blew.”

“I would have a problem with anyone who demeans me like he was during that campaign when he ran for president,” Fasano said. “And then to suck up like he is doing now? But Marco is the type of person who will do that. He’s always been like that. Whatever it takes.”

A return to the Senate

Rubio returned to DC in the spring of 2016 defeated and intent on quitting politics. His frustrations with Washington at the time had reached a tipping point after just one term in the Senate. And, as one of the upper chamber’s least wealthy members, he appeared ready to cash in with a private-sector gig.

None of the Florida Republicans eying his seat (which included a little-known congressional back bencher named Ronald DeSantis) much impressed GOP donors and leadership. To try to change his mind, the US Chamber of Commerce deployed one of its board members, Frank VanderSloot, an Idaho nutritional-supplement mogul who had helped bankroll Rubio’s White House bid.

The two met at Rubio’s office, where VanderSloot said he told Rubio: “America needs him to stay in the Senate.”

Rubio would later attribute his change of heart to the deadly mass shooting at Pulse, a popular night club for LGBTQ people in Orlando. The shooter killed 49 people, mostly gay men, and wounded 53 others. Rubio, who has spent his time in public office arguing against gun restrictions and opposing same-sex marriage, nevertheless told a conservative radio host at the time that he was “deeply impacted” by the tragedy and that made him reconsider “where you are most useful to your country.” Twelve days after the shooting, Rubio jumped back into the race just ahead of the filing deadline.

Trump and Rubio’s relationship also evolved quickly. While they sparred publicly on stage, after Trump won, he had Rubio to the White House for dinner, a turning point. And throughout his presidency, Trump relied on Rubio’s expertise of Latin America to help guide him on issues related to Venezuela, Cuba and Colombia.

“We used to joke that his side job was being the Western Hemisphere desk coordinator,” one former aide told CNN, noting that Trump called frequently to gauge Rubio’s opinion on matters in the region.

When the pandemic hit, it was Rubio and Democratic Sen. Ben Cardin of Maryland who worked with the administration to swiftly build out the Paycheck Protection Program, a loan program that gave small-business owners around the country a way to finance payroll and other expenditures during Covid.

“It was a really good experience working with him,” Cardin said. “We had to get a result, and we had to do it quickly so we had to forgo any of the usual shadowboxing that’s done around this place and reach decisions.”

Rubio also played a critical role in working closely with Trump’s daughter Ivanka Trump and helping design the child tax credit in the GOP’s 2017 tax bill, threatening to initially vote against the package unless the refundability of the credit in the bill was expanded, which eventually it was.

‘Don’t take the good ones’: GOP colleagues see Rubio as good pick for Trump

In the years between his presidential run and now, Rubio has spent less time building his public profile and more time investing in his relationships in the Senate. In conversations with nearly a dozen lawmakers, many observe Rubio has matured as a legislator and spent most of the last eight years keeping his head down, focused on his role on the Senate Intelligence Committee and being a resource to members.

“I think we look to him for good, solid advice,” said Sen. Lisa Murkowski, a Republican from Alaska. “I think when he moved from the failed effort … to run for president and then back into the Senate, I did see a change. He seemed more focused on some of the policy initiatives he was working on . … Was that because there was just more time in the Senate or was that because running for president can be a bit humbling? It can put anyone down a peg or two.”

Members also say they appreciate Rubio’s personal and stylish delivery in dry party lunches when he does speak up, which they say would be an asset if he were selected to be Trump’s VP.

“He’s kind of like a steady horse. He’s not going to speak unless he needs to speak. He’s not one of those flamboyant people who’s gonna try to stand out and be the face of every topic. He stays in his lane,” Alabama Sen. Tommy Tuberville said.

Asked whether Rubio has the experience to be the VP, Tuberville nodded.

“He’s the right age. That is the perfect age. He’s been hardened, he’s been called names by Trump himself, so I would not have any qualms,” Tuberville said. “I would hate to lose him in the Senate, but again we’ve gotta do what’s best in the next four years and the eight after that.”

Tuberville said he has joked with Trump “don’t take the good ones” from the Senate, but he argues he’s resigned himself to the fact that Rubio might be needed in the Trump administration more than in the chamber.

Others see Rubio’s personal story as an added advantage at a time when the GOP has made some inroads with Latino voters in states like Florida, Nevada and Arizona.

“Obviously, he is Cuban American, and Hispanics are increasingly coming to vote for Republicans. He speaks Spanish. He demonstrates a broader appeal than just a traditional Republican audience,” said GOP Sen. John Cornyn of Texas.

Trump has done little to tip his hand in the veepstakes. Rubio is seen as the preferred pick among many donors, and two of Trump’s trusted confidants – Kellyanne Conway and Sean Hannity – see him as a strong pick for Trump.

But while some have gone out of their way to flaunt their allegiance to Trump, Rubio has taken a more nuanced approach, not appearing with Trump at the courthouse in Manhattan with others such as Sen. J.D. Vance of Ohio, another VP contender. Rubio did, however, vote against a massive aid package for Ukraine in April, arguing it didn’t do anything to address the US’ own border. Rubio has also been more reluctant to say whether he will support the results of the election this cycle, telling NBC In an interview last month, “I think you are asking the wrong person. The Democrats are the ones that have opposed every Republican victory since 2000.”

Rubio – along with other senators – has also been helping Trump prep for the debate on Thursday and will be a surrogate for Trump in the spin room afterward.

Rubio does face a potential hurdle as Trump weighs his options. Trump and Rubio both live in Florida, and while there is no law preventing a president and vice president of the US being from the same state, the Constitution dictates that state electors must vote for a president and vice president “one of whom, at least, shall not be an inhabitant of the same state with themselves.” Meaning, Florida’s 30 Electoral College votes couldn’t go to two Floridians. In a close election, that could prevent either Trump or Rubio (presumably the latter) from reaching 270 electoral college votes to assume their office.

Rubio is open to moving if Trump selects him, and his residency is not a major concern among the former president’s advisers at the moment, a person with knowledge of both sides’ thinking told CNN. And while Rubio’s ascension to vice president could mean a vacant Senate seat, he says he’s not worried it could be lost to a Democrat.

“I would certainly feel a lot better about Florida today as a Republican than I would have a decade ago,” he quipped.