What happens within North Korea’s soccer team has been kept a closely guarded secret since its creation at the end of World War II.

Millions around the world caught a glimpse of the North Korean men’s team in two World Cups. The Cheollima – a mythical winged horse found in East Asian mythology and featured prominently in North Korean society – beat Italy 1-0 in a stunning performance in Middlesbrough, England, in 1966.

However, the team’s appearance at the 2010 tournament in South Africa was far less successful, as the team lost all three of its matches, including a 7-0 shellacking by Portugal.

But much like the reclusive nation itself, the team in recent years has fallen back into the shadows. Now in an exclusive interview with CNN Sport, retired North Korean midfielder An Yong Hak, who lives in Japan, has revealed what it’s like to play for the team.

The secrecy surrounding the North Korean national team was also evident in the case of star player Han Kwang Song.

At his peak, Han was on the roster of Italian giant Juventus and featured in its U-23 side, but then he vanished from the public eye for more than three years. He had been last spotted lifting a trophy with his most recent team, Qatari club Al-Duhail, in 2020 as UN Security Council resolutions later forced the repatriation of all North Korean workers abroad.

But that rapid change of fortune – from playing in top divisions in Italy and Qatar to being stuck at an embassy for the better part of three years – did not cause the striker to consider quitting soccer.

Almost out of nowhere, Han publicly reappeared last November with North Korea for its World Cup qualifiers, scoring a header in a 6-1 drubbing of Myanmar.

Retired North Korean midfielder An, who is now 45, laments Han being stuck in diplomatic limbo, saying it was unfortunate that the striker was unable to join Pyongyang’s leading domestic club team – 4.25 SC, or April 25 SC – sooner “to develop at an age when he could have advanced more.”

“He was stuck in an embassy in China, and he had to train alone for about two to three years. Last September, I think, they let him into the country,” An told CNN Sport, citing a North Korean official he spoke with. Han stayed in the embassy while the North Korean borders were shut due to the Covid-19 pandemic, An added.

Born in Japan with a North Korean passport, An represented North Korea on the pitch for 10 years, a national team career which Han told An he enjoyed witnessing, according to the retired international midfielder.

An recalled meeting Han for the first time in 2019 in Pyongyang, where he watched the former Cagliari striker play against South Korea, captained by Tottenham Hotspur star Son Heung-min, in a qualifier for the 2022 Qatar World Cup.

After that match, An said he was waiting to fly back home to Japan and coincidentally ran into Han and two other North Korean players – Pak Kwang Ryong and Choe Song Hyok – who were playing in Austria and Italy respectively at the time.

“[Han] told me that he had been watching me at the stadium when I played on the national team,” An said of his first interaction with the striker.

An recalled telling Han and the young North Korea players, “You guys have to do well from now on, and I’ll also go to Italy to cheer you guys on.’”

“Yes, please come! I’ll come pick you up,” Han replied to An.

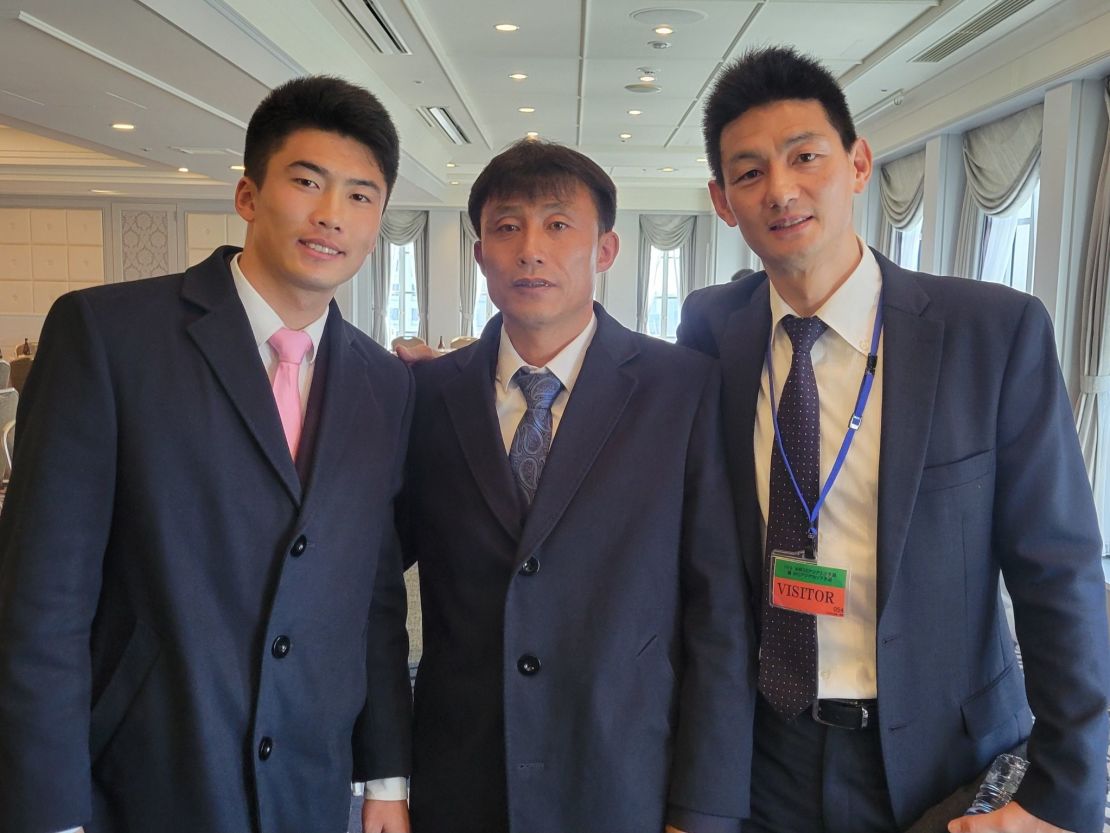

Then in March this year – five years and one pandemic later – the two met again, this time in Tokyo, Japan.

“I went to the hotel [the team was staying at] a day after the game, and I told him, ‘It’s been a long time,’” An said.

The pair talked about the previous day’s 2026 World Cup qualifying match where North Korea had lost to Japan by one goal.

“Han’s shot had hit the post and it didn’t go in, so we talked about how close he was [to scoring],” said An.

“Because of the sanctions, Han said, ‘I’m playing in [North Korea],’” said An, adding that there was not much time to get into deeper conversation.

He referred to Han as “the kind of talent that comes around every 10 or 20 years” and as someone who had the potential to become “a world-class player.”

“I want him to be a symbol of the DPRK [North Korea] national team… I would like to see him become a player like Son Heung-min or someone of that caliber,” An said of the 25-year-old Han.

‘A hoax’

Although North Korea has long isolated itself from the rest of the world, it has frequently participated in international sporting competitions, with the notable exception of during the Covid-19 pandemic.

When the Cheollima ended its 2010 World Cup run – losing every group stage match, against Brazil, Portugal and Ivory Coast – rumors and reports arose that the players and coaches were subjected to punishments back in Pyongyang.

Citing anonymous sources, Radio Free Asia reported that coach Kim Jong Hun was sent to do forced labor, while the players were subjected to “harsh ideological criticism,” except An and another North Korean-Japanese striker, Jong Tae Se. CNN could not independently verify this report.

An called such reports “a hoax.”

“It’s pretty hard to get information about DPRK, so there are still stories about people being sent to a coal mine after losing a match or being lectured for six hours, but there are no such stories at all, as far as I know,” An said, denying rumors about the isolated country, citing his 10-year career of playing for the national team.

“I think it’s time to put an end to that kind of false information,” he said.

Earning a spot at the 2010 World Cup marked only the second time North Korea had qualified for the world’s marquee soccer competition since 1966, when the Cheollima made it to the quarterfinals, losing to Portugal 5-3.

When North Korea secured its ticket to South Africa, the squad’s players were acknowledged by the regime with a certificate and an apartment in Pyongyang, a rare but well-known practice by the Kim regime to reward loyalty, according to state media KCNA and verified by An.

“Everyone received a certificate, and we each received an apartment in Pyongyang,” An said, adding that he did not get one because he is “Zainichi Korean.”

Koreans who migrated or were forced to move to Japan under colonial rule before the peninsula was divided in half are known in Japanese as “Zainichi Korean,” including their descendants.

They are eligible to apply for a North Korean passport or acquire South Korean nationality as they are not given Japanese citizenship – they are, however, legal residents in Japan and can gain citizenship through naturalization.

A third generation Zainichi Korean, An holds his North Korean nationality with pride.

“My grandparents kept their DPRK identity, although they could have chosen to live an easy life, so I didn’t want to easily change that identity of mine,” An explained, adding that he also considered South Korea his geographical home.

Another Zainichi Korean on the 2010 squad was Jong Tae Se, who grabbed the world’s attention as he broke down in tears during North Korea’s national anthem ahead of the squad’s 2-1 loss to Brazil.

Jong’s tears moved the fans and even An said, “Many Zainichi Koreans were extremely moved by it.”

“This Zainichi Korean, born and raised in Japan, had a big dream and made it come true. I was able to stand side-by-side with the athletes from my home country and sing the national anthem,” said An.

Earning respect

When An joined the North Korean national team upon receiving a call-up letter in 2002, he remembers not being immediately accepted by teammates.

“The players, coaches and managers didn’t know us very well. We needed to be accepted. We weren’t exactly welcomed from the beginning,” the retired midfielder said.

North Korean players have strong bonds, as the majority of them – except for those like Han who used to play abroad and Zainichi Koreans – reside in the country, and therefore, can be called up for the national team at almost any time, according to An.

To be accepted by the squad, newcomer An had to prove himself to the other North Korean players.

“I had to compete with the players in daily practice to win their trust and gain recognition. However, practice alone was not enough,” he said.

“I scored two goals in a World Cup qualifying match and, by producing a result, I was accepted as a member of the national team,” An said, referring to his brace in a 4-1 win against Thailand in the 2006 World Cup qualifiers.

It was then that the team welcomed An wholeheartedly and the squad members became “like a family” to him, he said.

“Usually, we’re apart, as I’m in Japan and they are in DPRK… it is difficult to keep in touch,” he said, reflecting on the unfortunate reality where he cannot even message his friends in Pyongyang.

Although, as fate would have it, An met his former teammate and current manager of the North Korean national team, Sin Yong Nam, last March. Sin asked An to visit Pyongyang to share his soccer experience with young, promising talent.

“When we met again after a long time, I felt nostalgic,” said An as he reflected on meeting his compatriots and former teammates after almost five years.

“If another opportunity arises, I would like to return to Pyongyang and, hopefully, provide some assistance to the national team,” An added.

CNN Tokyo’s Himari Semans and Rinka Tonsho contributed to this story