The whir of the helicopter shakes the marquee tent’s roof and kicks up a plume of dust that swirls through the thronging crowd, announcing the arrival of the man they’ve all come to see.

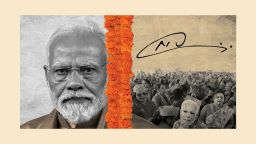

Chanting his name, waving his party’s flag and quoting his slogans, in many of their eyes he can do no wrong. Narendra Modi, India’s hugely popular but deeply polarizing prime minister, has landed in the battleground state of Uttar Pradesh as he campaigns for a third consecutive term in power.

Arrival at the rally in Aligarh, a three-hour drive from New Delhi, was preceded by a cacophony of horn-honking cars, motorcycles, and trucks all muscling their way in and out of traffic with few discernible lanes.

Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state of 240 million people, is right in the heart of the nation’s “Hindi belt”, the predominantly Hindi-speaking Indian states where support for Modi and the devotion of his followers is especially strong.

Win UP, so they say, and you win India.

As the sun glares down on the dusty field in Aligarh and temperatures soar to 38 degrees Celsius (100 Fahrenheit), the crowd don’t seem to mind.

“Modi! Modi! Modi!” they chant, as the prime minister speaks about the BrahMos – a nuclear-capable, land-attack cruise missile jointly developed by Russia and India – that will soon be assembled in a local factory.

With nearly 970 million eligible voters, India’s ongoing weekslong election – the world’s largest democratic exercise – is seen as critical in shaping the South Asian country’s trajectory over the next five years, with Modi widely expected to win. And here in Uttar Pradesh, a sense of pride is evident among the thousands gathered to hear the prime minister speak.

“We feel proud to have such kind of a leader,” says math teacher Pramod Charma. “Whatever he says, he does – that’s why he calls it ‘Modi’s guarantee.’ In politics, he is the biggest star right now. No one can replace him.”

In many ways Modi is part of the wider global wave of populist leaders with an authoritarian streak that have amassed a fervent voter base in recent years.

Modi projects himself as an outsider from humble origins. Born as the son of a tea seller in a small town in western Gujarat state, he does not fit neatly within the often privately educated, resolutely metropolitan, English-speaking template set by many previous Indian leaders.

To his devoted followers, he’s a man who has transformed the lives of ordinary Indians with his welfare and social policies – while cementing India as a key power broker. But to his critics, he’s a divisive leader, whose Hindu nationalist ambitions have given rise to growing religious persecution and Islamophobia, with many of the country’s more than 200 million Muslims fearing his re-election.

Just a day before this April 22 rally in Aligarh, Modi sparked a row over hate speech while campaigning in northwestern Rajasthan state when he accused Muslims – who have been present in India for centuries – of being “infiltrators.” He also echoed a false conspiracy voiced by some Hindu nationalists that Muslims are displacing the country’s majority Hindu population by deliberately having large families.

That speech stirred widespread anger and calls for election authorities to investigate the comments. BJP spokespeople subsequently said Modi was talking about undocumented migrants.

And Modi’s remarks did little to shake the faith of his devoted followers in Aligarh.

Lawyer Gaurav Mahajan says this is the fifth Modi campaign rally he has attended. “(He is the) most powerful leader in the world,” he says. “Indians have faith in Modi.”

With just two out of seven phases of voting complete, Indian politics remains unpredictable. But with no one in the opposition camp to possess the kind of brand name and star quality that Modi has, analysts say his re-election is widely expected.

Opposition leaders have meanwhile accused Modi’s right-wing government of becoming an electoral autocracy by attempting to rig the vote, weaponizing state agencies to stifle, attack and arrest opposition politicians, and undermining democratic principles. They also warn that Modi’s brand of Hindu nationalism is uncorking dangerous religious divides in a country with a long and tragic history of sectarian bloodletting.

The BJP’s national spokesperson has previously said the party is not prejudiced against Muslims and that democracy is protected under the constitution.

Modi is expected to remain on the campaign trail until India’s next prime minister is named in early June, traversing the huge country, visiting city after city and delivering his roaring speeches that attract the masses.

In Aligarh, the mood feels like a jovial pep rally, and there is none of the divisive rhetoric that was on show in Rajasthan.

When the crowd spots our camera, as if on cue, they begin to chant: “Modi! Modi! Modi!”

Old and young, the sentiment in the crowd appears universal.

“There are no words to express the goodness of Modi,” says engineering student Narayan Pachaury, 17.

“No one is bigger than him.”