It may be spring, but it’s not too soon to look ahead to summer weather, especially when El Niño – a player in last year’s especially brutal summer – is rapidly weakening and will all but vanish by the time the season kicks into gear.

El Niño’s disappearing act doesn’t mean relief from the heat. Not when the world is heating up due to human-driven climate change. In fact, forecasters think it could mean the opposite.

What this summer’s weather could look like

El Niño is a natural climate pattern marked by warmer than average ocean temperatures in the equatorial Pacific. When the water gets cooler than average, it’s a La Niña. Either phase can have an effect on weather around the globe.

By June, forecasters expect those ocean temperatures to hover close to normal, marking a so-called neutral phase, before La Niña builds in early summer, according to NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

But the strength of El Niño or La Niña’s influence on US weather isn’t uniform and varies greatly based on the strength of the phenomena and the season itself.

The influence of El Niño or La Niña on US weather isn’t as clear-cut in the summer as it is in the winter, especially during a transition between the two phases, said Michelle L’Heureux, a climate scientist with the Climate Prediction Center.

Temperature differences between the tropics and North America are more extreme in the winter, L’Heureux explained. This allows the jet stream to become quite strong and influential, reliably sending storms into certain parts of the US.

In the summer, the difference in temperature between the two regions isn’t as significant and the obvious influence on US weather wanes.

But we can look back at what happened during similar summers to get a glimpse of what could come this summer.

In short: It’s not cool.

The summer of 2016 was one of the hottest on record for the Lower 48. La Niña conditions were in place by midsummer and followed a very strong El Niño winter.

Summer 2020 followed a similar script: La Niña conditions formed midsummer after a weak El Niño winter but still produced one of the hottest summers on record and the most active hurricane season on record.

Then there’s the fact that these climate phenomena are playing out in a warming world, raising the ceiling on the extreme heat potential.

“This obviously isn’t our grandmother’s transition out of El Niño – we’re in a much warmer world so the impacts will be different,” L’Heureux, said. “We’re seeing the consequences of climate change.”

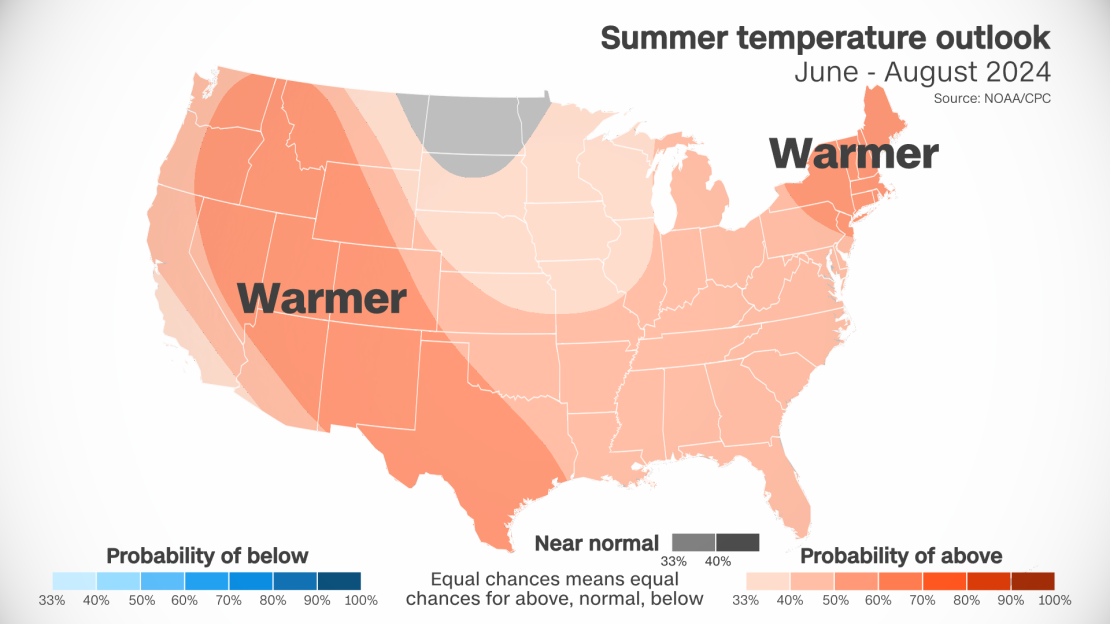

Current summer temperature outlooks for the US are certainly bringing the heat.

Above-average temperatures are forecast over nearly every square mile of the Lower 48. Only portions of the Dakotas, Minnesota and Montana have an equal chance of encountering near normal, above- or below-normal temperatures.

A huge portion of the West is likely to have warmer conditions than normal. This forecast tracks with decades of climate trends, according to L’Heureux.

Summers have warmed more in the West than in any other region of the US since the early 1990s, according to data from NOAA. Phoenix is a prime example. The city’s average July temperature last year was an unheard-of 102.7 degrees, making it the hottest month on record for any US city. It was also the deadliest year on record for heat in Maricopa County, where Phoenix is located.

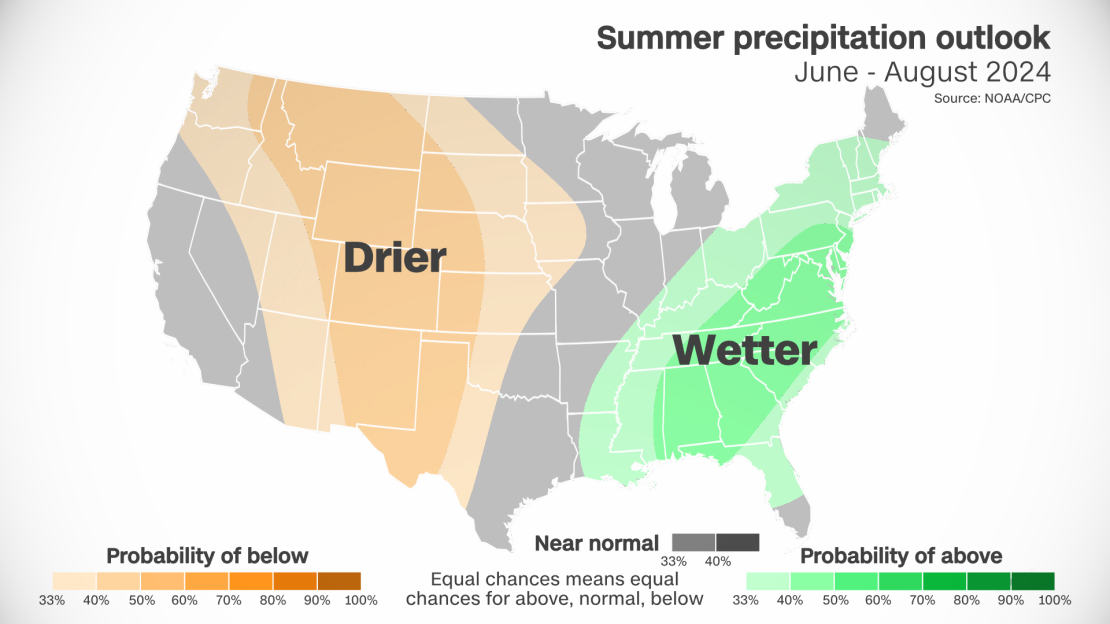

Forecasts also show a worrying precipitation trend for parts of the West.

Large sections of the West and the central US are likely to be drier than normal. This dryness, combined with above-normal heat, which only amplifies the dryness, could be a recipe for new or worsening drought.

Wetter than normal conditions are in the forecast from the Gulf Coast to the Northeast. Stormy weather could be a consistent companion for much of the East – but whether it comes from typical rain and thunderstorms or tropical activity won’t be known for months.

A brutal summer also predicted in the water

Heat isn’t the only threat to look out for.

The strengthening La Niña conditions, coupled with ocean temperatures which have been at record highs for over a year, could supercharge the Atlantic hurricane season.

A warming world generates more fuel for more tropical activity and stronger storms. La Niña tends to produce favorable atmospheric conditions to allow storms to form and hold together in the Atlantic.

Early this month, forecasters at Colorado State University released their most active initial forecast ever.

“We anticipate a well above-average probability for major hurricanes making landfall along the continental United States coastline and in the Caribbean,” the group said in a news release.