Editor’s Note: Miles O’Brien is the science correspondent for PBS NewsHour and an aviation analyst for CNN. He was previously a staff correspondent and anchor with CNN, based in Atlanta and New York. The CNN Original Series, “Space Shuttle Columbia: The Final Flight,” uncovers the events that ultimately led to disaster. New episodes air at 9 p.m. ET/PT Sunday, April 14. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author. View more opinion on CNN.

On January 16, 2003, I was in a place I loved doing a job I loved. I was the space correspondent for CNN and had been covering NASA and the shuttle program for the network for nearly 11 years.

I was at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida to cover the launch of the space shuttle, Columbia. My team and I were at “the press mound” three miles away from the launch pad, which is as close as they let anybody.

As always, I was thinking about what I would say if things went really wrong. It was my responsibility to be that person.

The September 11 terror attack was still a fresh memory, and this shuttle crew included the first Israeli astronaut, Ilan Ramon. So, there was a lot of focus on security. But I was also thinking about the fragility of the space launch system. Engineers had been most recently vexed by a series of cracks in the shuttle’s main engines, and I was wondering if that had been solved.

But there was always something like that to worry about. The shuttle consisted of a spacecraft called an “orbiter” attached to a giant fuel tank and two solid rocket boosters. It had about a million parts that all had to work in synchronicity for a launch to go off without a hitch. There were a lot of redundant systems to add measures of safety, but also several so-called “single-point failure” scenarios that could most certainly lead to the loss of the vehicle and its crew. Indeed, the fact that it ever worked at all is still pretty amazing to me.

In pictures: Space Shuttle Columbia's final flight

I always worried about the first 8.5 minutes of a shuttle mission the most. That’s the point when the main engines stop firing as the orbiter has enough velocity to remain in low-Earth orbit. At that point, the astronauts are in a relatively stable situation; you can safely walk away from the camera.

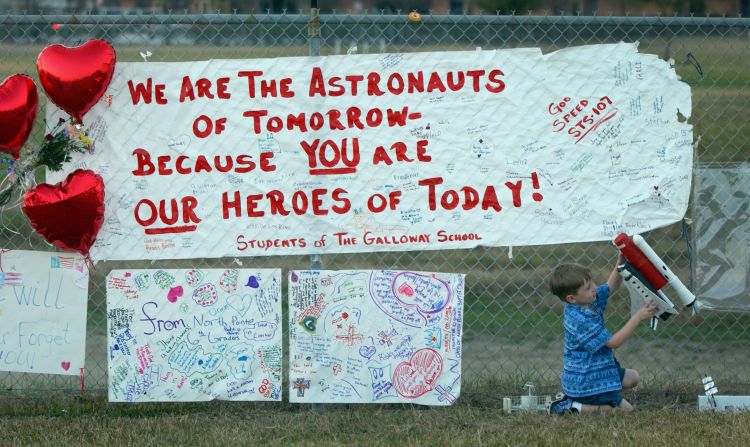

As part of the post-launch routine, NASA began sharing several replays of the launch from various cameras trained on the vehicle. And that was when we saw it.

Producer Dave Santucci called me into our live truck, and said, “You got to look at this.” It was kind of a grainy image of what looked like a puff of smoke, as if someone dropped a bag of flour on the ground and it broke open. We played it over and over again, and it did not look good at all.

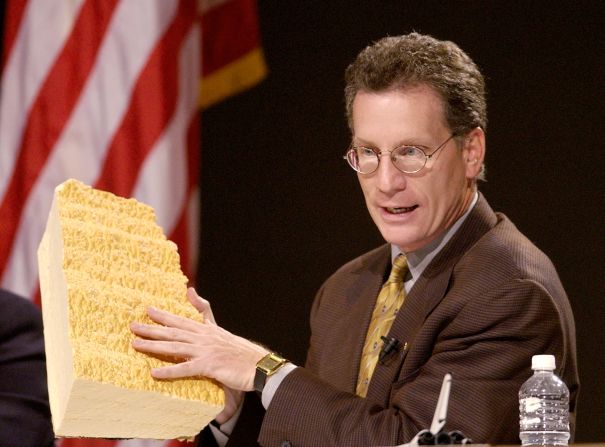

The giant orange fuel tank was filled with super cold liquid hydrogen and oxygen, so it was enveloped in insulating foam. A big piece of the foam had broken away near a strut called the “bipod,” striking the leading edge of the orbiter’s left wing. It was made of reinforced carbon to protect the aluminum structure of the spacecraft from the searing heat of re-entry from space.

I reached out to some of my sources inside the shuttle program. Everyone had seen it, of course, but the people I spoke with cautioned me not to worry. The foam was very light, and it had fallen off on earlier missions and nothing of concern had happened as a result.

So, I decided not to write a piece on the foam and instead I turned my attention to preparing for coverage for another huge story: the US invasion of Iraq. I wish I hadn’t taken my eye off the ball. Space was my beat, and I was uniquely positioned to put this concerning event into the public domain.

Like NASA’s leadership, I went through a process of convincing myself that it was going to be okay. But I had this sinking feeling. It didn’t feel right.

A spacecraft re-entering the atmosphere at 17,500 miles an hour — much faster than a rifle bullet — is enveloped in a glowing inferno of plasma. It’s beautiful — the same phenomena that creates the northern lights — but obviously you want the crew to be protected from it.

So, any time a shuttle was coming home, I was worried. But in this case, I was a little more anxious.

I was doing double duty the morning of February 1, 2003. In addition to being the network’s space correspondent, I was also co-anchor of the weekend morning show — produced out of CNN Center in Atlanta.

When I walked into the newsroom early that morning, I asked the assignment desk to reach out to our affiliates underneath Columbia’s flight path. It was an unusually clear February morning all across the continental United States, and the orbiter was on a diagonal path from northern California to the Florida space coast. I thought it would be a stunning sight — worth seeing and recording.

I called the assignment desk at an affiliate in Dallas to see if they had assigned a photojournalist to capture the streaking space object that was the returning space shuttle. It was a fateful request, as it ensured that we would all bear witness to the breakup of Columbia. Streaking objects — plural.

Once settled on the couch with co-anchor Heidi Collins, I opened a phone line that tapped into the Mission Control audio. I wanted to make sure I could hear what was happening while simultaneously anchoring the morning show. I was interviewing comedian and actress Janeane Garofalo, who was sharing her concerns about the impending invasion of Iraq, when the communication between the ground and the orbiter became non-routine.

Producers in the control room realized the gravity of the situation, and we cut to a commercial break to get me off the couch. As I was making my way across the newsroom, I started heaving.

I knew in an instant that they were all gone. There was no survivable scenario. I was sickened. It was like a body blow.

Somehow I got my act together and started talking.

Get Our Free Weekly Newsletter

- Sign up for CNN Opinion’s newsletter

- Join us on Twitter and Facebook

I felt like it was my responsibility to mention the foam strike, to get the information out there to the public. About an hour after Columbia had disintegrated, I shared with a huge global audience what I knew.

Here’s what I said then: “Let’s try to put together what we know and give you a sense of where this investigation might be headed. Take a close-up here. That bipod is the place where they think a little piece of foam fell off and hit the leading edge of that wing.”

During the mission, I could have easily done a story about the foam strike, spreading the word that some NASA engineers believed there may be some reason for concern. What if I had done that? It might have made a difference.

Columbia’s crew had no capability of seeing the left wing, but of course, the US has an unparalleled fleet of spy satellites in space. Aiming one at the orbiter to assess any possible damage was a possibility.

But what could they have done? Columbia’s sister ship, Discovery, was already on a launch pad. It would’ve been heroic and perhaps a little foolhardy, but a rescue mission would not have been impossible, and I feel certain that if NASA managers saw that gaping hole in Columbia’s wing, they would’ve tried.

We will never know for sure, but I do know how so many of us on the ground failed to do our jobs during that mission. It still haunts me.

![KENNEDY SPACE CENTER, FLA. - In this view, Space Shuttle Columbia is almost dwarfed by the rolling clouds of smoke and steam across Launch Pad 39A. Following a flawless and uneventful countdown, launch of Columbia on mission STS-107 occurred on-time at 10:39 a.m. EST. The 16-day research mission will include FREESTAR (Fast Reaction Experiments Enabling Science, Technology, Applications and Research) and the SHI Research Double Module (SHI/RDM), known as SPACEHAB. Experiments on the module range from material sciences to life sciences.. Landing of Columbia is scheduled at about 8:53 a.m. EST on Saturday, Feb. 1. This mission is the first Shuttle mission of 2003. Mission STS-107 is the 28th flight of the orbiter Columbia and the 113th flight overall in NASA's Space Shuttle program. [Photo courtesy of Scott Andrews]

Date Created:2003-01-16](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/240327131341-01-space-shuttle-columbia-sts-107-final-flight-unf.jpg?c=16x9&q=w_1280,c_fill)