Editor’s Note: Alice Randall is a country music songwriter and publisher who’s been in the business for more than four decades. Her book “My Black Country: A Journey Through Country Music’s Past, Present and Future,” was published this month. The views in this commentary are her own. Read more opinion at CNN.

Over a long career in music, I’ve known the profound alienation one feels as an unacknowledged member of the country music family. I first experienced it when I showed up in Nashville years ago as a 23-year-old country music songwriter, one of very few Black people working in the genre at the time.

I felt the same way a dozen years later — even after having “made it” with a number one song on the country charts (the song “XXX’s and OOO’s” that I co-wrote with Matraca Berg) but not always getting the acceptance of my White peers.

As a Black country music composer who has been in the business for 41 years, however, I’ve seen something new in just the past few weeks: a landscape markedly altered following the release of Beyoncé’s “Cowboy Carter.”

Now she’s made history as the first Black woman ever to top Billboard’s Top Country Albums chart. It’s an achievement I celebrate as much as if it were my own.

For years, I had populated my own country songs with Black characters only to discover, when the songs were performed by White artists, those Black identities had been erased from country radio’s audio landscape and purged from mainstream America’s understanding of the south and the west.

Suddenly, in Beyoncé’s country compositions (and I use the term advisedly, since she has described it as a “Beyoncé album and not a collection of country music songs), I experience a whole Black world infused with our understanding of the country genre. I hear Black moonshiners and Black cowboys, Black nature lovers and Black ghosts, Black angels, Black freedom fighters, gunslingers and Black shotgun riders.

You can also find Black mamas and babies; good Black lovers (the ones who “put a ring on it”) and bad ones (who get entrapped by women like “Jolene.”) You can find all of that and more — striding, strolling, grinding and floating through the 79 minutes of “Cowboy Carter.”

It could be the start of something truly wonderful. It could start a groundswell of long overdue recognition of the overlooked Black country legends and hope for the Black country stars of the future.

At last, a seat at the table

Beyoncé’s new album is many things, but perhaps more than anything, it is a giant gathering to which a global audience has been invited. But for Black performers in particular, it offers a seat, at long last, at a gathering of the country music family.

For a lot of Black folk, family reunions are where we share our history, our hearts, our faith, our values, our identity. It’s where we define and sometimes broaden the parameters of who is one of us, and at times delineate who’s not kin — who’s not invited to the barbecue.

I can’t help but recall the many times when our White country music family failed to acknowledge us. I think back to March 1983, when the Country Music Association celebrated its 25th anniversary with a concert at DAR Constitution Hall in Washington, DC, in front of an audience that included President Ronald Reagan, Vice President George H.W. Bush, Sen. Ted Kennedy and the presidents of several major record labels and performance organizations.

As I write in my book “My Black Country,” at that gathering, country music legend Roy Acuff announced to the assembled audience, “Nobody in country music is there alone… Country music is a family.”

But he then proceeded to call not a single Black name — not even DeFord Bailey, the Grand Ole Opry’s first superstar who had helped jumpstart Acuff’s own career. It was two days after that concert that I, undeterred and undaunted by his omission to make a little room for Blacks working in the genre, headed south and west to Nashville to begin my career as country songwriter and country song publisher.

Admittedly, country was not an obvious career choice for me in the eyes of some. I was born in Detroit in 1959, the same year and the same city that R&B mecca Motown Records was founded. My parents were not in the music industry but they hung out with people who were — my father was a friend of Anna Gordy, daughter of Motown mogul Berry Gordy and wife of soul music legend Marvin Gaye. My dad made sure I knew that Anna Records was co-founded by Anna Gordy — a woman — a year before Motown’s historic founding.

Black Detroit was fixated on R&B, and while friends and family suspected I might pursue a career in music, no one thought it would be in Nashville. But for some reason I can’t fully explain, country music was always a thing for me — it was a passion I shared with my mother, aunt and grandmother, and it feels like it was always my destiny.

Broadening the guest list

“Cowboy Carter” is not Beyoncé’s first foray into country. She blew into Nashville in 2016 with “Daddy Lessons” and was summarily rebuffed by the industry. She certainly wasn’t treated like the member of the country music family. So she decided to host her own family reunion — and she significantly broadened the guest list.

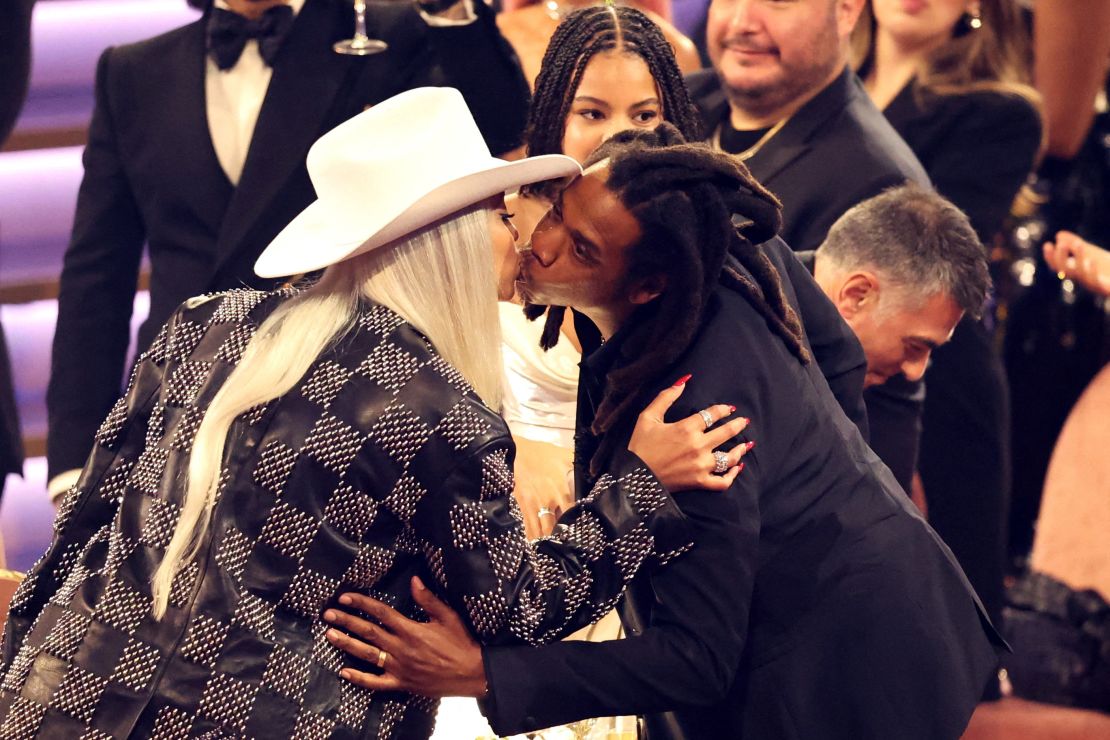

Listening to “Cowboy Carter,” we travel backward in time on the voice of Linda Martell, the first Black woman to sing on the stage of the Grand Ole Opry in August 1969. We travel forward in time too, on the voice of Rumi Carter, Beyoncé’s six-year-old daughter.

A few established names also got invitations to appear on the album — notably Dolly Parton, Willie Nelson and Miley Cyrus, daughter of country music royalty Billy Ray Cyrus. Yes, pillars of the White country establishment have graced their brilliant Black cousin with their presence.

At the same time, Beyoncé uses her power to acknowledge all the Black relations, living and dead, who are a part of the country music family but have not been claimed as such. “Cowboy Carter” redefines the genre by centering on storytelling and four elemental truths: Life is hard; God is real; the road, whisky and familial love are significant compensations; and the past was better than the present.

Black relations country never knew it had

With “Cowboy Carter,” Beyoncé also resolves what has been called the Saturday night/Sunday morning paradox in country music: The desire to party with the devil on Saturday night and sing with angels on Sunday morning. Beyoncé teaches us that these desires are not opposites; they are aligned.

My favorite song on the album is “Ya Ya.” It is the big tent at the reunion. Listening to it for the first time I felt as if I was meeting a cousin I had never known, one who had the same odd obsessions that I had that we both believed no one on Earth shared. Beyoncé also connects Black and European musical traditions.

As I write in “My Black Country,” “I have imagined Black country and country to be born as an art form, as an aesthetic, in the year 1624 near Jamestown, Virginia. William Tucker, the first Black infant born in the British colonies that would become America, was born that year near that place. I have imagined his mother weaving English ballads she heard with African melodies she knew and singing to her son.”

We have much to learn at this family reunion, a lot about the surprising people who are in the family that you didn’t even know about or knew about and didn’t know were in the family. For some, I hope it will be an introduction to a Black country singer called Stoney Edwards who sang a song called “Blackbird,” released in 1976 the year that America celebrated its 200th birthday.

Get Our Free Weekly Newsletter

- Sign up for CNN Opinion’s newsletter

- Join us on Twitter and Facebook

As I wrote in my book, the song is a country parental-advice-song like no other: A child who has been dismissed with a racial epithet is encouraged by loving parents to imagine himself “a proud and soaring ‘Blackbird’ who in its flight is an indictment of the American Eagle being celebrated in the bicentennial moment.”

“Cowboy Carter” is an album that resists the limits of the country music genre while highlighting its aesthetics. Beyoncé exhibits the classic formula of Celtic ballad + Black influence + evangelical Christianity = Country Music.

At last, the Black faces and voices in that equation are no longer unacknowledged. The gathering no longer leaves some contributors on the outside looking in. It’s a whole new family reunion.