The 2024 Atlantic hurricane season isn’t here yet, but is already shaping up to be one for the books, with more hurricanes and named storms predicted in a pre-season forecast from Colorado State University than ever before.

This June through November could see 23 named storms in all, including 11 hurricanes and five Category 3 or higher “major” hurricanes, according to the university’s Atlantic hurricane season forecast, released Thursday.

“This is the most active April forecast that we have ever issued,” lead forecaster Phil Klotzbach told CNN. “Our prior highest hurricane forecast in April was 9 hurricanes, which we have called for several times” since the forecasts began in 1995.

With the caveat that early outlooks aren’t set in stone given the “considerable changes that can occur in the atmosphere-ocean between April and the peak” of the season, it’s still an ill omen for a particularly active storm season.

And, researchers say they have “above-normal confidence” for this April’s predictions.

“We anticipate a well above-average probability for major hurricanes making landfall along the continental United States coastline and in the Caribbean,” the group said in a news release.

On average, the Atlantic season brings 14 named storms, with seven hurricanes, three of them major. Last hurricane season had 20 named storms including seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes.

The only other Colorado State outlooks to predict this many hurricanes were mid-season forecasts in August 2005 and 2020 – which ended up being the two most-active Atlantic seasons on record.

“The highest number of hurricanes that we have predicted at any lead time is 12 … which we forecast in August of 2020,” Klotzbach said, adding that was still an undershot, with 14 hurricanes total that year. “We also forecast 11 hurricanes in August of 2005. That season ended up with 15 hurricanes.”

The researchers will issue updates to the forecast on June 11, July 9 and August 6.

El Niño to La Niña

With the forecast in, the next question is: Why?

You may have heard talk of El Niño during last year’s hurricane season. Now, we’ll be dealing with the opposite natural climate phenomenon, La Niña, and its potential impacts will be key this season.

El Niño is when the surface waters of the central and eastern Pacific are warmer than normal.

El Niño heats up the atmosphere and changes circulation patterns around the globe; it also influences global weather, including cyclone seasons. When the Pacific is warmer, the region typically sees more tropical cyclones, but the Atlantic sees fewer, thanks to more upper-level winds that rip apart storms and prevent them from forming.

As El Niño’s opposite, La Niña suppresses those upper-level winds, making conditions ideal for hurricane formation and intensification.

There is a 55% chance for La Niña to develop from June to August and a 77% chance from September to November, according to a March forecast from NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.

A warm world favors hurricanes

The overarching impacts of climate change are also, as ever, at play.

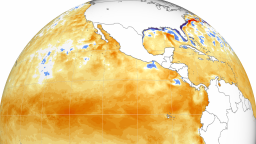

Planet-warming pollution is driving global and ocean temperature rise, and the world’s oceans have now experienced an entire year of unprecedented heat thanks to this human-caused warming and El Niño.

And as the planet warms, the impacts of hurricanes are becoming more dangerous.

Global sea levels are also on the rise, driven mainly by the rapid melting of ice sheets and glaciers. A rise of only a couple of inches can make a dramatic difference in how far inland a hurricane’s storm surge can travel.

A warmer climate also means there will be more water vapor available in the atmosphere to potentially fall as rain.

The water in the Atlantic, particularly where most hurricanes form, has been record-warm. A warm Atlantic in spring usually means warmer water during hurricane season because it creates conditions that stop water-cooling winds from forming, Colorado State University researchers said in Thursday’s news release.

And more warm water means more chances for storms.

“A very warm Atlantic favors an above-average season, since a hurricane’s fuel source is warm ocean water,” the release said. “In addition, a warm Atlantic leads to lower atmospheric pressure and a more unstable atmosphere. Both conditions favor hurricanes.”

CNN’s Eric Zerkel contributed to this report.