When a man called to confess he had shot his wife, was armed with an AR-15 and planned to kill himself, police in Jefferson City, Missouri raced to the scene.

Heavily armed officers ordered the homeowner to walk outside with his hands up. From the doorway, a middle-aged man emerged. It was Jay Ashcroft, Missouri’s Secretary of State who minutes earlier was gearing up for a workout on his home treadmill.

“I just couldn’t believe this was happening to me,” Ashcroft, a Republican and the state’s top election official, said in an interview with CNN. “It was very surreal.”

What went down at Ashcroft’s house that night was a potentially deadly hoax called “swatting” in which a caller makes a bogus crime report intended to trigger a massive law enforcement response to a target’s residence.

The practice has emerged as a major concern for election officials ahead of this year’s presidential election, but combatting swatting is fraught with unique challenges that authorities are seemingly unprepared for: The inherent anonymity of swatting and the technological tools that fuel it have outpaced law enforcement’s ability to tamp it down, according to interviews with 16 current and former election and law enforcement officials.

Threats have become pervasive, law enforcement officials say, as technology has enabled the calls to become more realistic sounding and harder to trace. Artificial intelligence now allows malicious pranksters to mimic the voices of targeted individuals, while proxy servers and encrypted-communication apps add layers of privacy. A cottage industry of purported swat-for-hire accounts has popped up on social media, seeking to monetize the practice.

CNN identified multiple such accounts online and conducted interviews with people linked to two of them who declined to identify themselves or offer definitive proof of their services, though they offered to discuss their methods and motivations. Both accounts claimed to have made thousands of dollars through swatting and denied fear of legal consequences due to their processes of using software for anonymity.

“i dont think ill ever get caught,” stated one who responded to questions in a messaging app and claimed to use text-to-voice programs and VPNs – virtual private networks – to contact law enforcement.

Another threat to election officials

At least four swatting incidents have been aimed at the homes of senior officials who oversee or work to secure elections since December. Aside from Ashcroft, who is running for governor in Missouri, those hoaxes involved officials’ homes in Maine, Georgia and Virginia. Each case remains under investigation, local authorities said.

The incidents come amid a broader wave of swatting and election-related threats. An FBI database set up last year has tracked about 600 swatting incidents. Separately, a Department of Justice taskforce launched in 2021 has reviewed more than 2,000 allegations of hostility, harassment, abuse, or threats to election officials and staffers, a department spokesperson said.

One such threat occurred in January, when an anonymous account warned election officials and others in at least 23 states that “multiple explosives” had been hidden in state capitol buildings that would “make sure you all end up dead,” according to an email obtained by CNN. The message triggered evacuations and bomb sweeps even though the FBI later called the incident a “hoax.”

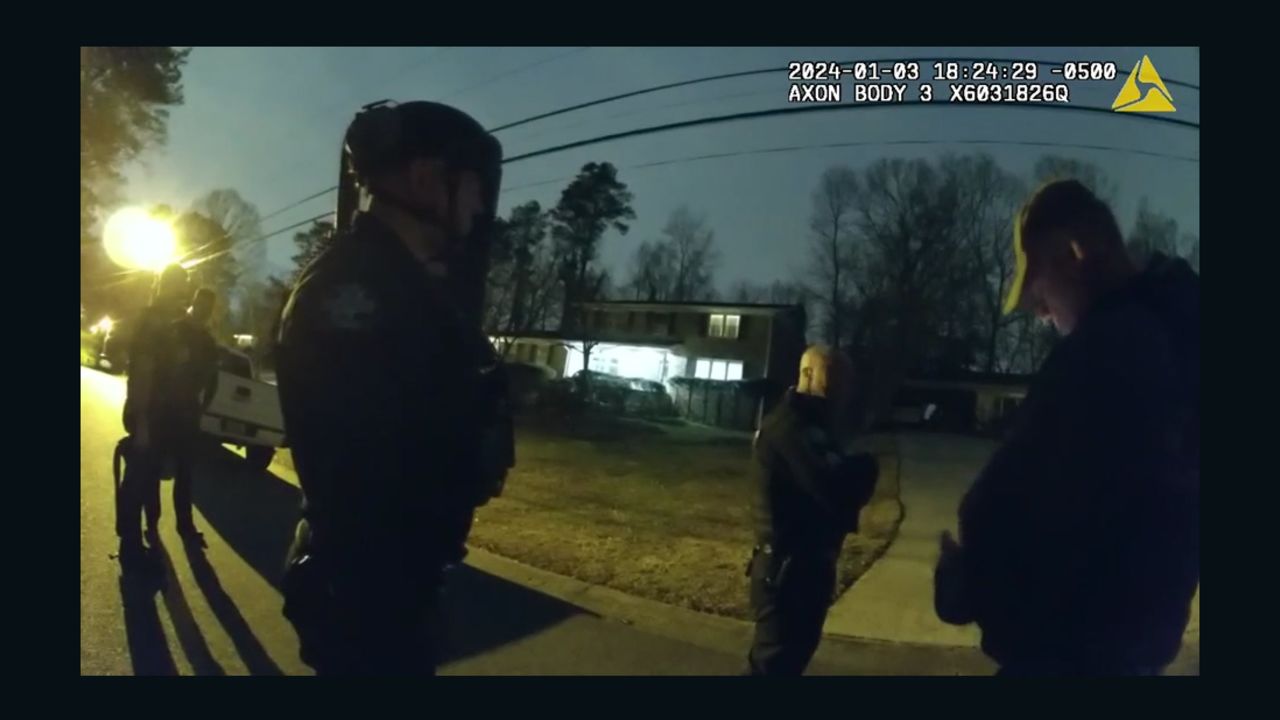

That same day, Gabriel Sterling, the chief operating officer for Georgia’s secretary of state, tweeted about that threat and warned of “chaos agents sowing discord” in an election year. Hours later, Sterling’s home was swatted.

Local police received a report that a drug dealer had shot someone at Sterling’s address. Even though an officer quickly identified the situation as a possible swatting incident because the address belonged to Sterling, a call-taker reported “possibly” hearing gunshots on the call and police continued to respond, according to a dispatch recording.

An officer soon determined the call to be “unfounded,” according to a police report.

“I anticipate we’ll probably see some more of these as we get closer and closer to the election,” said Sterling, who noted the challenge of identifying those responsible for such hoaxes. “This could be a kid in Britain who is bored. This could be a concerted effort. This could be Russians. This could be Americans. That’s one of the things about swatting … you can’t trace the individual. It’s very, very difficult in most cases.”

The evolution of swatting

The phenomenon of swatting emerged in the early 2000s, according to the FBI, which investigated a case of five individuals motivated by “bragging rights and ego” who swatted more than 100 victims between 2002 and 2006.

The trend expanded to target celebrities such as Justin Bieber and Ashton Kutcher in 2012 and became a way for gamers to prank one another while playing online games, such as “Call of Duty.”

But swatting has had deadly consequences. A hoax call led to a Kansas police officer shooting an unarmed man in 2017. A Tennessee man reportedly died of a heart attack after police, responding to a swatting call, told him to come out of the house with his hands up during an incident in 2020.

That danger has not stopped swat-for-hire accounts from appearing on social media, though authorities have brought charges in some swatting cases.

In a high-profile case unveiled in January, an investigation that involved multiple FBI field offices and local agencies led to the arrest of Alan Winston Filion, a 17-year-old from California.

Court documents filed in the case allege Filion “is responsible for hundreds of swatting and bomb threat incidents” and allegedly linked him to accounts that offered swat services, including one that advertised “$50 for a major police response” and “$75 for a bomb threat/mass shooting threat.” An affidavit further alleges Filion swatted FBI agents and would “likely” threaten other government officials.

Filion has pleaded not guilty. His attorney did not respond to a request for comment.

Challenges to combatting swatters

Such cases often present complex obstacles for investigators, current and former law enforcement officials said. For example, a swatter’s use of VPNs and messaging apps may require authorities to send subpoenas to compel the companies behind those platforms to share potentially identifying information, but even then, the companies may not comply or may not hold the requested information.

“It is a cat-and-mouse game and we are playing catch up,” said Jennifer Doebler, a former intelligence analyst with the FBI. “The point is not that swatters have the upper hand. It’s we are at the mercy of technology, and it’s growing faster than we can.”

Moreover, while some states have enacted laws to stiffen penalties for swatting, no federal law specifically criminalizes the practice, said Lauren R. Shapiro, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice who has written about swatting.

“Without a specific law against swatting, prosecutors at the state and federal levels are forced to determine which aspects of the swatting incident matches specific elements in current laws for the purpose of charging,” said Shapiro, who noted that some serial swatters have received relatively lenient penalties. “What’s disheartening is the sentencing sometimes is very low.”

In January, Republican Sen. Rick Scott of Florida and others introduced legislation to expand a criminal hoax statute to specifically prohibit swatting and impose stiff penalties.

That bill came after Scott’s home in Naples, Florida was swatted in December. A recording of the swatting call obtained by CNN featured an artificial-sounding voice stating, “Hello, I just killed my wife and I have a hostage.”

An officer who answered the call struggled to understand the muffled voice’s attempts to share Scott’s address and responded, “Sir, I could not hear the address. It was very mechanical.” The voice eventually communicated the address after repeated attempts. “I want 10-grand in cash and I will let the hostage go,” the voice added.

The incident remains under investigation, a Naples police administrator said.

“Most of the time, there’s not an arrest,” said an officer currently investigating a swatting case who was not authorized to speak to the press. “It’s not like we’re going to issue a warrant for a juvenile child outside of our state, so it ends up being a lot of work with nothing at the end.”

Preparing for the worst

Such incidents have prompted some election officials to take extra precautions.

Swatting was featured in a tabletop exercise for election officials in New Jersey last month, a spokesperson for the secretary of state told CNN. The exercise included a hypothetical situation in which “coordinated swatting calls” occurred after a decision to keep polls open, which in turn caused election workers to flee amid “chaos.”

In Georgia, Sterling said there have been a series of meetings between county election directors and law enforcement to flag their personal information in police databases to help prevent swatting.

Arizona’s secretary of state’s office is working with election officials and law enforcement to mitigate potential incidents, said a spokesperson who also noted that elected officials now have contact information for threat-intelligence officers in each county.

“Make no mistake, just because swatting is a fake emergency doesn’t make it any less dangerous,” Maine’s Secretary of State Shenna Bellows, whose home was swatted in December, told CNN in an interview. “We are preparing for the worst but expecting and hoping for the best.”

The incident that targeted Bellows’ home came after her decision to remove former President Donald Trump from the state’s 2024 primary ballot based on the 14th Amendment’s “insurrectionist ban” (the Supreme Court last week ruled that Trump could not be removed from the ballot in any state). Following Bellows’ decision, an anonymous account posted her personal information – including her home address – online.

Likewise, the swatting incident involving Ashcroft’s home occurred days after he posted a tweet that criticized the decision in Maine to remove Trump as “disgraceful” and floated the idea that something similar could happen to President Joe Biden.

Asked about the swatting trend facing election officials, Ashcroft said, “There’s a coarsening of a political debate, where instead of taking our arguments to the ballot box or, as I would say, cussing and discussing in a polite way … people are looking for other ways to do things.”

“It’s wrong if it happens to Democrats; it’s wrong if it happens to Republicans,” Ashcroft added.

Such incidents have prompted The Elections Group, a consulting group led by former election officials, to begin sharing resources on swatting with election workers and incorporating the topic into trainings.

The group advises officials to share names and addresses of key staffers with local police and limit sensitive personal information shared on social media.

Tina Barton, a former adviser to the US Election Assistance Commission who currently works with The Elections Group, said swatting poses an additional layer of strain on an already stressed election system. A wave of election officials have departed their roles since November 2020, when false claims of a stolen election proliferated.

“What we have seen criticism turn into are threats to life and threats to family,” Barton said. “I do have concerns that good people won’t run for office, or good people will walk away, and I see it every day.”