Editor’s Note: Kara Alaimo, an associate professor of communication at Fairleigh Dickinson University, writes about issues affecting women and social media. Her book, “Over the Influence: Why Social Media Is Toxic for Women and Girls — And How We Can Take It Back,” was published by Alcove Press on March 5, 2024. Follow her on Instagram, Facebook and X. The opinions expressed in this commentary are her own. Read more opinion on CNN.

When scholar Kaitlyn Regehr’s team set up accounts and searched for information commonly sought out by young men in the UK, such as information on loneliness, mental health and fitness, the amount of misogynistic content suggested on TikTok’s “For You” page quadrupled over just five days. In response to the report, TikTok told The Guardian that “misogyny has long been prohibited on TikTok and we proactively detect 93% of content we remove for breaking our rules on hate. The methodology used in this report does not reflect how real people experience TikTok.”

“Extremist misogyny that was once really segregated to … [less mainstream] platforms is now disseminating onto much more popular platforms like TikTok and permeating into youth culture more generally,” Regehr, an associate professor at University College London who studies online extremist groups, told me. A few years ago, it would have been considered shocking to post on mainstream social networks about a woman’s anatomy being disfigured after violent sex, Regehr pointed out. Now, “we’re moving into this new act where that type of dark edgy humor is not that shocking, and that is unique compared to other forms of extremism.”

This kind of content started out in the so-called “manosphere,” where many men came together to share their hatred towards and grievances against women. Social media provided a space for them to find one another and commune, making their beliefs even more extreme. Over the past several years, these views have spread onto more mainstream platforms.

Friday is International Women’s Day. This year, women are, in many ways, less safe and have fewer rights and resources than we did just a few years ago. It’s not just that progress has stalled — we’re going backwards. As I argue in my new book, “Over the Influence,” there are many reasons for this, but one we need to start to contend with is how the violence and abuse directed at women on social networks is making the offline world more dangerous for us.

It’s common to use the phrase “in real life” (or just IRL) to refer to things that happen offline. This phrase hasn’t just become antiquated — it’s now dangerous, because it negates the very real effects of what’s happening online. What our society is sharing and seeing on social media is profoundly affecting the way women are viewed and treated in all aspects of our lives.

For example, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey, released last year, found that the percentage of US high school girls who said they’d been forced to have sex increased from 12% to 14% from 2011 to 2021. There are about 15.4 million students in high school in the US. Assuming that roughly half are female, if we applied these findings, approximately 154,000 more girls were forced to have sex.

Among many factors, one thing that could account for this is the violence against women and girls that is celebrated on social apps. A wide body of research confirms that people who witness acts of violence in the media are more likely to commit acts of violence.

As this way of thinking and posting about women becomes more normalized, it’s unsurprising that people are taking greater liberties to abuse women and deprive us of rights and resources offline. Activists in Africa told The New York Times that killings of women increased during the pandemic — when we all, of course, spent more time online. Women also experienced greater domestic violence during the pandemic when they were trapped in their homes with sometimes abusive spouses.

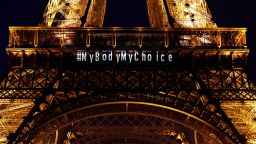

By June 2023, a year after the US Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, half of US states had passed laws banning or restricting access to abortion. “We are the first generation in American history to have to tell the next generation they have less rights than us,” Palestinian-American feminist activist Linda Sarsour told me when I interviewed her for my book.

Of course, right-wing groups were working to repeal Roe long before X (formerly Twitter) and TikTok arrived on the scene. But for the high court to reverse women’s rights to terminate non-viable pregnancies that threaten their lives, it had to believe that women would passively accept losing this potentially life-saving legal protection. One thing that could have factored into their calculus that this was politically and socially feasible was the way our culture has shifted to accept and even glorify misogyny — an extremely online trend.

This might also help explain why the US government thinks it’s acceptable to deprive women of essential resources. In September, Congress let billions of dollars in badly-needed temporary funding for childcare provided by the American Rescue Plan Act during the pandemic expire rather than making it permanent. As a result, The Century Foundation estimates that over 70,000 childcare programs will close, leaving 3.2 million kids without care and forcing many moms to stop working or reduce their hours.

Similarly, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) enjoyed 25 years of bipartisan support in Congress until last year, when lawmakers failed to provide additional funds needed due to rising participation and food costs. As a result, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates 2 million pregnant and postpartum women and young children won’t get the help they need in order to eat.

Sometimes the chain of events seems even clearer: In China, for example, a 23-year-old woman died by suicide last year after being viciously attacked on social media. The bullying was prompted by a picture she shared of herself visiting her grandfather in the hospital to tell him she’d been admitted to grad school. Some accused her of being a prostitute because she had pink hair; others falsely claimed her grandfather was her husband. Another Chinese woman, who was a high school teacher, recently died from a heart attack that her daughter blamed on hackers, who disrupted classes she was teaching online and prevented her from sharing her slides.

A common question I have been getting when I speak about my work is why I don’t just recommend that women delete our apps since I believe they are so toxic. But this wouldn’t address the fact that others are using social networks to spread misogyny and hate that is endangering women and girls.

To solve this problem, tech companies need to stop hosting misogynistic content on their platforms. They need to get better about identifying such content and rapidly removing it, using both human moderators and artificial intelligence. When we see friends or family members posting it, we need to do what activist Loretta Ross terms “calling them in” or offline conversations about why it’s not okay (clapping back to trolls on social media just boosts their engagement). We should also report content that violates the community standards of social networks to the social networks we see it on. While tech companies are infamous for often not taking action in response to these reports, if we all did this en masse, it would send a powerful message to tech companies that users are demanding that they stop allowing people to be abused on their platforms.

Get Our Free Weekly Newsletter

- Sign up for CNN Opinion’s newsletter

- Join us on Twitter and Facebook

And we need to counter this content by posting about powerful women and issues we care about and following, reposting and engaging with the content of other people who do so. To add my own contribution, I’ve posted a list of “feminists to follow” on my website. If we all started sharing more content that empowers women, social networks’ algorithms would serve us more of it.

What happens on social media doesn’t stay on social media. This means women can no longer end the abuse we’re up against without a serious status update on social networks.