The consecration of a controversial Hindu temple symbolizes the seismic shift from India’s secular founding values, analysts say, as Prime Minister Narendra Modi disregards norms separating religion from state in his push to win a rare third term this year.

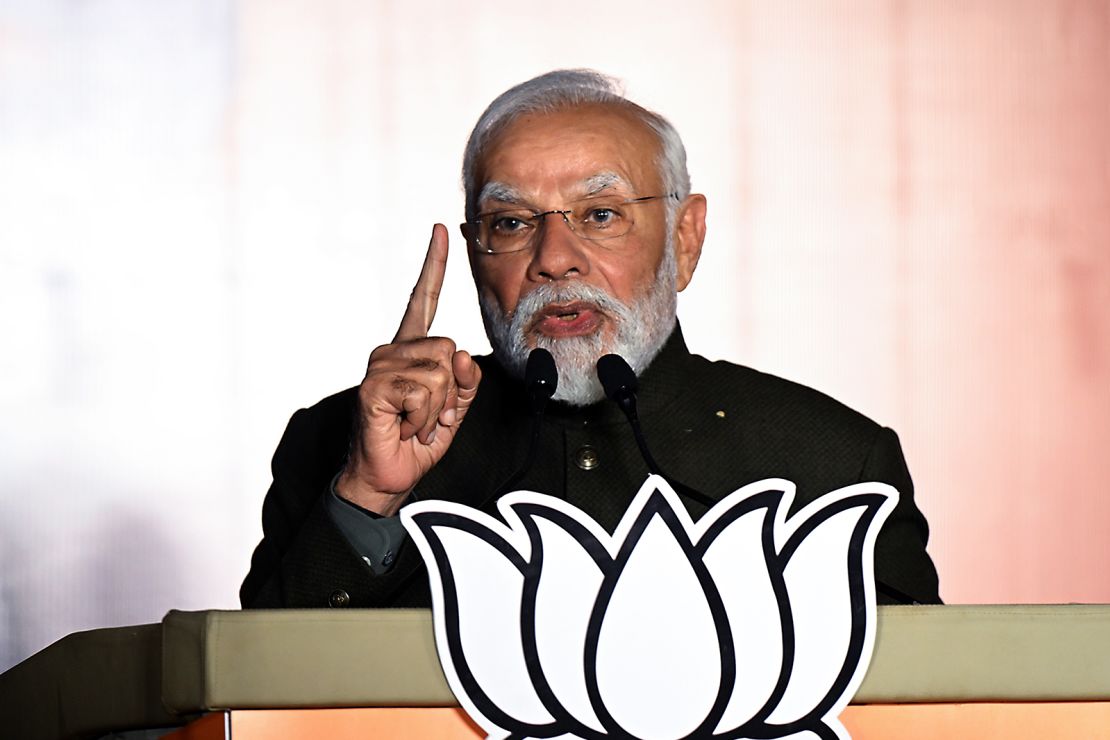

Modi presided over a lavish opening ceremony last month of the Ram Janmabhoomi Mandir in the sacred town of Ayodhya, fulfilling a longstanding promise to voters that helped propel him and his Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to power in 2014.

“(Today) is the beginning of a new time cycle,” Modi said at the new temple honoring Hindu deity Lord Ram. “After centuries of waiting, our Ram has arrived.”

Modi’s vision of a “divine India” is a far cry from the ideas of the modern country’s founding fathers. During nearly a decade in power, the prime minister has enveloped himself in the language of religion in pursuit of his Hindu nationalist agenda, isolating millions among India’s sizable religious minorities.

“This moment is both a culmination of a political project that has been 100 years in the making, and a new departure for India, no longer a secular republic,” said political scientist Gilles Verniers, a senior fellow at the Centre for Policy Research in New Delhi.

“India becomes a de facto Hindu nation, where the task of building national Hindu religious symbols falls to the state. And in which its leader officiates simultaneously as prime minister and head priest for the country.”

‘King of Gods’

The Ram Janmabhoomi Mandir stands on the site of the Babri Masjid, a 16th century mosque that was destroyed by hardline Hindus in 1992, setting off a wave of deadly sectarian violence not seen in India since its bloody 1947 partition.

The temple’s inauguration was attended by thousands of hand-picked guests – including cricket legend Sachin Tendulkar and billionaire industrialist Mukesh Ambani – and streamed live to millions across the country.

In Ayodhya, billboards celebrating the temple’s opening featured an image of Hindu deity Ram alongside Modi’s face, with the leader of his BJP even dubbing the prime minister “The King of Gods.”

Modi fasted for 11 days in a purification ritual before the event and visited temples across the country, performing customs sacramental to India’s majority faith.

He publicly called himself “an instrument” of Lord Ram, anointed by the divine to “represent all the people of India.”

At the consecration, Modi presided over the “Pran Pratishtha” – the unveiling of the much-anticipated Ram idol – taking on a role typically reserved for priests. The move was well received in most quarters, with his supporters praising the leader’s actions.

But for some Hindus, Modi’s actions represent a betrayal of their religion for political capital.

“This is obviously an electoral stunt, it should not be happening in the name of my faith,” said Indian American activist Sunita Viswanath and member of the US-based Hindus for Human Rights group in a statement the day before the temple opening.

“Modi is not a priest, so leading this ceremony for political gain is both technically and morally wrong. This weaponization of our religion tramples what’s left of India’s secular democratic values.”

Yet, in blurring the lines between state and religion, Modi has achieved what his predecessors were unable to, analysts say.

“Much of this is about solidifying his image in India as someone who is devout, someone who delivers on his promises,” said Foreign Policy editor-in-chief and former CNN New Delhi bureau chief, Ravi Agrawal.

“This is a very popular move, and while it’s being criticized… it remains popular in a country that is 80% Hindu.”

Hindu right emboldened

Modi rose to power in 2014 with a pledge to reform India’s economy and usher in a new era of development – but he also heavily pushed a Hindutva agenda, an ideology that believes India should become a land for Hindus.

When he stood for reelection in 2019, Modi’s Hindutva policies became more brazen, according to analysts.

A few months after winning, he announced he was stripping the statehood of India’s only Muslim-majority territory, Jammu and Kashmir, and turning it into two union territories while bringing it under federal control. Later that year, his government passed a controversial citizenship law considered by many to be discriminatory against Muslims.

And he reiterated his party’s desire to build the Ram Temple on the contested holy site.

Many Hindus believe the Babri Masjid was built on the ruins of a Hindu temple, allegedly destroyed in 1528 by Babar, the first Mughal emperor of South Asia. For years, they rallied to tear down the mosque and make way for a temple.

The dispute reached its climax in 1992 when, spurred on by the BJP and right-wing groups, Hindu hardliners attacked the mosque, triggering widespread communal violence that killed more than 2,000 people nationwide.

In a victory for Modi and his supporters, India’s Supreme Court in 2019 granted Hindus permission to build the temple, ending the decades-long dispute – but dealing a blow to millions of Muslims who fear that religious divisions are becoming more pronounced under Modi’s BJP government.

The Indian government denies it is discriminating against minorities, but analysts say last week’s festivities have only emboldened right-wing Hindus to act with impunity against minorities.

Communal tensions rose in western Maharashtra state, with three reported altercations between Hindus and Muslims, according to local police.

In a separate incident in central Madhya Pradesh state, a group of right-wing Hindus was seen placing saffron flags on top of a Christian church. The color is closely associated with Hinduism.

“India has become more majoritarian. India has become more nationalist. India has become more pro-Hindu,” Agrawal said. “This is partly due to the government’s ability to point to India’s history and the wrongs they perceive India to have faced.”

Shedding colonialism, correcting injustice

Since assuming power nearly a decade ago, Modi has positioned himself as a disrupter of India’s colonial legacy, often in speeches marked by emotive language.

He has emphasized the need to “liberate (India) from the slavery mindset,” making steps to steer the country away from what the government has called the “vestiges of British rule.”

Similarly, Modi has also made comments about India’s erstwhile Islamic rulers, the Mughals, who ruled much of the country from 1526 to 1858. Many hardline Hindus believe the era was a period of oppression under Muslim rule, a view that has also been echoed by some members of the BJP.

Hindu groups have for decades claimed the Mughals destroyed Hindu temples, building mosques and other monuments in their place. Many of these cases are now being debated in courts across the country, in a move Indian liberals fear could spark further violence and disharmony.

Just this week, a court in the city of Varanasi ruled that Hindus can pray inside the disputed Gyanvapi mosque built by former Mughal ruler Aurangzeb - purportedly on the site of a destroyed Hindu temple – in another major religious dispute.

“Aurangzeb severed many heads, but he could not shake our faith,” Modi said in a 2022 speech, referring to the ruler who died more than three centuries ago.

As the country heads toward a national election expected to be held in April and May, the government “sees itself as addressing these injustices,” said Foreign Policy’s Agrawal.

Gilles, the political scientist, said last week’s display of Hindu nationalism at the Ram Temple shows the strength of the alliance between the BJP and India’s business and cultural elites.

The temple’s inauguration was a “dark day for India’s religious minorities,” he said.

“(They) have officially become second-class citizens.”