Hanadi Gamal Saed El Jamara, 38, says sleep is all that can distract her children from the aching hunger gnawing at their bellies.

These days, the mother-of-seven finds herself begging for food on the mud-caked streets of Rafah, in southern Gaza.

She tries to feed her kids at least once a day, she says, while tending to her husband, a cancer and diabetes patient.

“They are weak now, they always have diarrhea, their faces are yellow,” El Jamara, whose family was displaced from northern Gaza, told CNN on January 9. “My 17-year-old daughter tells me she feels dizziness, my husband is not eating.”

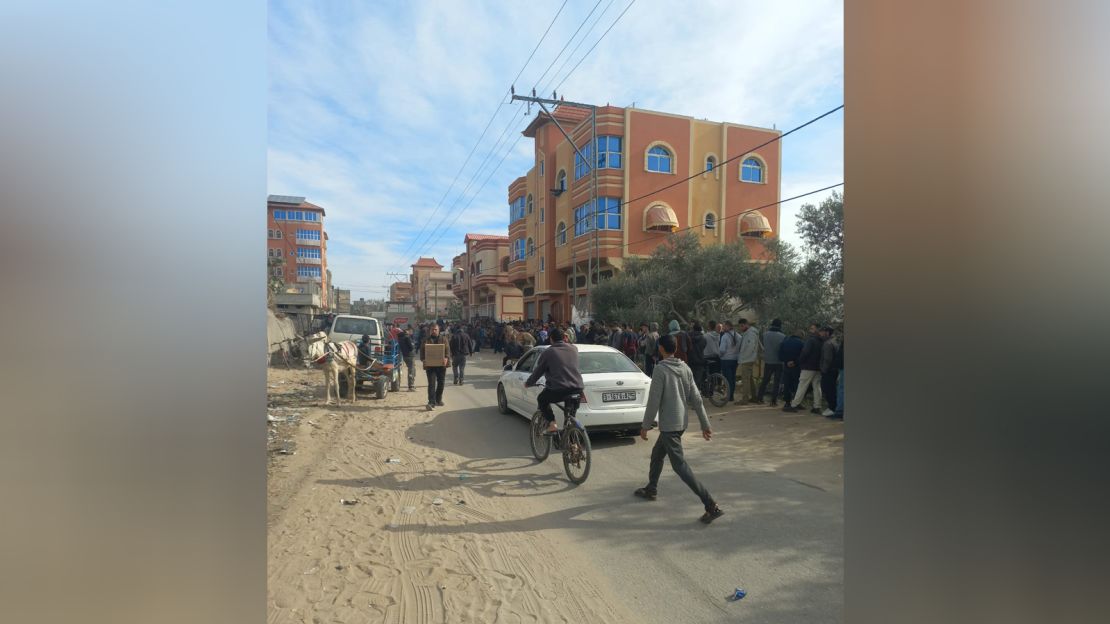

As Gaza spirals toward full-scale famine, displaced civilians and health workers told CNN they go hungry so their children can eat what little is available. If Palestinians find water, it is likely undrinkable. When relief trucks trickle into the strip, people clamber over each other to grab aid. Children living on the streets, after being forced from their homes by Israel’s bombardment, cry and fight over stale bread. Others reportedly walk for hours in the cold searching for food, risking exposure to Israeli strikes.

Even before the war, two out of three people in Gaza relied on food support, Arif Husain, the chief economist at the World Food Programme (WFP), told CNN. Palestinians have lived through 17 years of partial blockade imposed by Israel and Egypt.

Israel’s bombardment and siege since October 7 has drastically diminished vital supplies in Gaza, leaving the entire population of some 2.2 million exposed to high levels of acute food insecurity or worse, according to the Integrated Food Security and Nutrition Phase Classification (IPC), which assesses global food insecurity and malnutrition. Martin Griffiths, the UN’s emergency relief chief, told CNN the “great majority” of 400,000 Gazans characterized by UN agencies as at risk of starving “are actually in famine.” UN human rights experts have warned “Israel is destroying Gaza’s food system and using food as a weapon against the Palestinian people.”

Over more than 100 days, Palestinians in Gaza have seen mass displacement, neighborhoods turned to ash and rubble, entire families erased by war, a surge in deadly disease and the medical system wrecked by bombardment. Now starvation and dehydration are major threats to their survival.

“We are dying slowly,” reflected El Jamara, the mother in Rafah. “I think it’s even better to die from the bombs, at least we will be martyrs. But now we are dying out of hunger and thirst.”

Israel’s strikes on Gaza since the October 7 Hamas attacks have killed at least 26,637 people and injured 65,387 others, according to the Hamas-run Ministry of Health. The Israeli military launched its campaign after the militant group killed more than 1,200 people in unprecedented attacks on Israel and says it is targeting Hamas.

People in northern Gaza ‘eat grass’ to survive

Mohammed Hamouda, a physical therapist displaced to Rafah, remembers the day his colleague, Odeh Al-Haw, was killed trying to get water for his family.

Al-Haw was queueing at a water station in Jabalya refugee camp, in northern Gaza, when he and dozens of others were struck by Israeli bombardment, Hamouda said.

“Unfortunately, many relatives and friends are still in the northern Gaza Strip, suffering a lot,” Hamouda, a father-of-three, told CNN. “They eat grass and drink polluted water.”

Israel’s blockade and restrictions on aid deliveries mean stocks are desperately low, driving up prices and making food inaccessible to people across Gaza. Shortages are even worse in the northern parts of the strip, according to the UN, where Israel concentrated its military offensive in the early days of the war. Communication blackouts stifle efforts to report on starvation and dehydration in the region.

“People butchered a donkey to eat its meat,” Hamouda says friends in Jabalya told him earlier this month as shortages worsened.

In what could be a serious blow to humanitarian efforts, several Western countries have suspended funding to the main UN agency in Gaza, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) in recent days over explosive allegations by Israel that several of its staffers participated in the October 7 attacks. The UN fired several employees in the wake of the allegations.

Jordan’s foreign minister urged those countries suspending funding to reconsider, saying UNRWA was a “lifeline” for more than 2 million Palestinians in Gaza and that the agency shouldn’t be “collectively punished” over allegations against a dozen of its 13,000 staff.

‘No clean water’

Gihan El Baz cradles a toddler on her knee while comforting her children and grandchildren, who she says wake each day “screaming” for food.

“In the shelters, there is not enough food, the sun sets on us, and we haven’t even had any lunch,” El Baz, who lives with 10 relatives inside a weather-worn tent in Rafah, told CNN. She nurses her husband, who she says fell and broke his arm while dizzy from exhaustion.

“There are no drinks, no clean water, no clean bathrooms, the kid cries for a biscuit and we can’t even find any to give her.”

Displaced parents in Rafah, where OCHA reported more than 1.3 million residents of Gaza have been forced to flee, say the stress of being unable to protect their children from bombardment is compounded by their inability to provide enough food. Limited access to electricity makes perishable goods impossible to refrigerate. Living conditions are overcrowded and unsanitary.

“People are forced to cut down trees to get firewood for heating and preparing food. Smoke is everywhere and flies spread widely and transmit diseases,” said Hazem Saeed Al-Naizi, the director of an orphanage in Gaza City who fled south with the 40 people under his care – most of whom are children and infants living with disabilities.

Hamouda, the displaced health worker, used to feed his children – aged six, four and two – a mixture of fruits and vegetables, biscuits, fresh juices, meat and seafood. This year, he said, the family has barely eaten one meal a day, living on dried bread and canned meat or legumes.

“Children are being violent towards each other to get food and water,” said Hamouda, who works at Abu Youssef Al-Najjar Hospital and volunteers at a nearby shelter. “I can’t stop my tears from falling when I talk about these things, because it’s very hurtful seeing your kids and other kids hungry.”

All 350,000 children under the age of five in Gaza are especially vulnerable to severe malnutrition, UNICEF reported last month.

Increased risk of dying

The “scale and speed” of potential famine in Gaza will consign child survivors to a lifetime of health risks, said Rebecca Inglis, an intensive care doctor in Britain who regularly visits Gaza to teach medical students.

The first 1,000 days of a child’s life are “absolutely critical” for physical growth and cognitive development, Inglis told CNN. Malnourished children have an 11-fold increased risk of dying compared to well-nourished children, she said. Vitamin and mineral deficiencies force the body into an “emergency shut-down state” where it loses the ability to make energy, put on weight, or maintain kidney and liver functions, she added.

Malnourished children, especially those with severe acute malnutrition, are at greater risk of dying from illnesses like diarrhea and pneumonia, according to the World Health Organization. Cases of diarrhea in children under age five have increased about 2,000% since October 7, UNICEF said.

Hamouda said his own children have diarrhea, cold and flu symptoms. “The children’s bodies are dehydrated … their skin is dehydrated.”

In times of severe stress, pregnant women are more likely to miscarry or give birth prematurely, health workers previously told CNN. Gaza is home to 50,000 pregnant women, according to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Babies who do survive in utero are more likely to be born underweight and are therefore at higher risk of dying, Inglis said. Starving and dehydrated mothers cannot provide enough breast milk for their babies.

Challenges to food distribution, blocked aid

Shadi Bleha, 20, is trying to feed a family of six. Twice a week, they receive two water bottles, three biscuits and “sometimes” two cans of food from UNRWA, he said.

“It is not enough to meet my family’s needs at all,” the student, who is sheltering in a tent in Rafah, told CNN.

Palestinians in southern Gaza also told CNN that poorly regulated humanitarian distribution means some civilians get no aid at all, while those who do may sell for profit.

In other cases, vendors purchase aid from merchants and trade at markets for inflated costs. Some people with cars travel further afield to get water, returning to displacement camps to resell water for hiked prices. Intensified strikes also raise prices. Three weeks ago, a 25-kilogram bag of flour cost $20 in Khan Younis, according to Al-Naizi, but after the IDF intensified attacks on the southern city, it became $34.

Others say they receive humanitarian parcels that have been opened, with items missing. Dates, olive oil and cooking oil found in aid packages are reportedly sold on the black market for more than double their value.

On January 21, Israel’s Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories (COGAT), said 260 humanitarian trucks were “inspected and transferred to Gaza,” marking the highest number since the start of the war.

But aid agencies say it is not enough. The Israeli military in January only granted access to a quarter of aid missions planned by humanitarian agencies to Gaza, OCHA said on January 21. CNN reached out to COGAT for comment on OCHA’s statistics and did not get a reply.

The WFP has called for new aid entry routes, more trucks to pass through daily border checks, fewer impediments to the movement of humanitarian workers, and guarantees for their safety. On January 5, the agency reported six bakeries in Deir al-Balah and Rafah had restarted operations, but three remained out of use. “Bread is the most requested food item, particularly as many families lack the basic means for cooking,” it said.

Meanwhile, Israel’s military offensive has razed at least 22% of Gaza’s agricultural land, according to OCHA. Livestock are starving and fresh produce is hard to come by.

Juliette Touma, director of communications for UNRWA, said the needs of displaced civilians in Gaza outweigh the amount of aid allowed into the strip by authorities. “We simply don’t have enough, and we cannot keep up with the overwhelming needs of people on the ground,” she told CNN. “That makes the delivery of humanitarian assistance extremely challenging.”

Both UNRWA and WFP told CNN while they could not verify reports of individuals reselling aid for higher prices, it is entirely possible given the scale of desperation and hunger in Gaza.

“It’s absolute chaos and people are absolutely desperate, people are absolutely hungry,” added Touma. “The clock is indeed ticking for famine.”

WFP told CNN that aid distributions are based on verified beneficiary lists and observed by food monitors, who “report back that the food is delivered to its intended recipients.”

“Sometimes families make a personal decision to sell WFP food in exchange for other household items that they might need. To be clear, any food distributed by the WFP is not for sale,” the agency said in a statement.

The war has also caused widescale loss of employment in Gaza, further draining residents’ purchasing power as prices rocket.

Hamouda now spends $250 per week to buy food and supplies for his family – compared with $50 to $70 before the war. In an invoice seen by CNN, monthly supplies for orphans under Al-Naizi’s care were purchased from a procurement company for $6,814 – including $2,160 for infant formula alone. Before the war, the same quantity of formula would have cost $1,680.

“We live almost in a jungle where war, murder, the greed of merchants, the injustice of institutions in distributing aid, and the absence of government lead to this deadly chaos,” al-Naizi said.

Correction: This story has been corrected to reflect that CNN reached out to COGAT about OCHA’s figures on aid missions, not the IDF.

CNN’s Nourhan Mohamed, Christiane Amanpour, Eyad Kourdi, Celine Alkhaldi and Hira Humayun contributed reporting.