A version of this story appeared in CNN’s What Matters newsletter. To get it in your inbox, sign up for free here.

New Hampshire, which has conducted the first presidential primary for more than 100 years, is clinging to its spot on the 2024 election calendar.

Why is New Hampshire’s primary first?

New Hampshire’s state government jealously guards its status as the first-in-the-nation primary. Iowa traditionally conducts its contest earlier than New Hampshire, but that is a caucus, a meeting at a specific time, rather than a primary with secret ballot voting.

New Hampshire state law, passed in 1975, requires that its primary be conducted before any other state’s.

The state is not representative of the country as a whole. It has fewer than 1.5 million residents and is overwhelmingly White. But voters in New Hampshire take their role as the first primary state seriously, and it is an interesting feature of the American system that anyone who wants to be president will have to get his or her message across to everyday people in New Hampshire living rooms and make appearances in the state’s diners.

While its state government is controlled by Republicans, New Hampshire is frequently listed as a battleground state in general elections. But starting in 2004, it has voted for the Democrat in every presidential election.

Who can vote in New Hampshire’s primary?

Registered Republicans and Democrats vote in their own primaries, but it’s important to note that in New Hampshire, independent voters can also take part by asking for either a Republican or Democratic ballot.

Who is ahead in New Hampshire?

Trump is the clear front-runner and holds 50% support among likely Republican primary voters in the Granite State, according to a CNN poll conducted by the University of New Hampshire and released Sunday. Trump’s closest competitor, former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, stands at 39%. Both have gained supporters since the last CNN/UNH poll in early January (when Trump held 39% to Haley’s 32%), as the field of major contenders has shrunk. Other major candidates, including Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who had early buzz in the campaign, have dropped out of the race.

New Hampshire’s Republican Gov. Chris Sununu endorsed Haley and has spoken out against Trump for the former president’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election. But Sununu recently calibrated his position to make clear he would vote for Trump if the former president wins the Republican primary race, even if he’s a convicted felon.

Haley has focused on undeclared voters, hoping they can help her against Trump’s committed Republican base. Even if Haley scores a victory against Trump in the state, she will then have to figure out how to translate a message that works in the Northeast for the rest of the country’s Republicans.

How many delegates are at stake?

New Hampshire’s primaries and their results get a lot of scrutiny because they come first, but there are only a relatively few delegates on the line. Ultimately, it is winning delegates that secure primary nominations.

New Hampshire gets 22 delegates in the Republican primary process – less than 1% of the total delegates who will vote at the convention this summer. All of the state’s Republican delegates will be awarded to candidates proportionally based on their statewide primary performance, but candidates need to win at least 10% of the vote to be eligible for delegates.

Democrats are only giving New Hampshire 10 delegates this year, punishment for conducting the primary earlier than the party wanted. More on that below.

Does New Hampshire have a good track record of picking the nominee or the president?

New Hampshire’s primary has been the site of some poll-defying upsets, such as when then-Sen. Gary Hart unexpectedly won the Democratic primary in 1984 or when, on the Republican side, then-Sen. John McCain defeated George W. Bush in 2000.

It has a pretty good track record of picking the Republican nominee. Only three times since the 1950s has the winner of the New Hampshire primary not gone on to be the Republican nominee. In two of those years – 1964 when Henry Cabot Lodge won the primary and 1996 when Pat Buchanan won – Republicans lost the general election. Bush won the White House in 2000 despite losing in New Hampshire.

New Hampshire has not fared as well on the Democratic side. In elections where there is no Democratic incumbent, the ultimate primary winner hasn’t gone on to win the nomination since John Kerry in 2004. This year, even though Joe Biden is the incumbent, he isn’t on the ballot.

Why isn’t Biden on the ballot in New Hampshire’s primary?

The Democratic situation in 2024 is complicated since Biden’s name will not appear on the New Hampshire primary ballot.

The Democratic National Committee wanted South Carolina, which has a more diverse base of Democratic voters, to go first.

New Hampshire’s state government, which is controlled by Republicans, had no interest in handing over its first primary status to appease the DNC. Biden also lost the New Hampshire primary on his way to the White House in 2020. His victory in the South Carolina primary reignited his campaign.

The weird result is that Biden, an incumbent who is all but guaranteed to be his party’s nominee in November, won’t have his name appear on the 2024 primary ballot in New Hampshire.

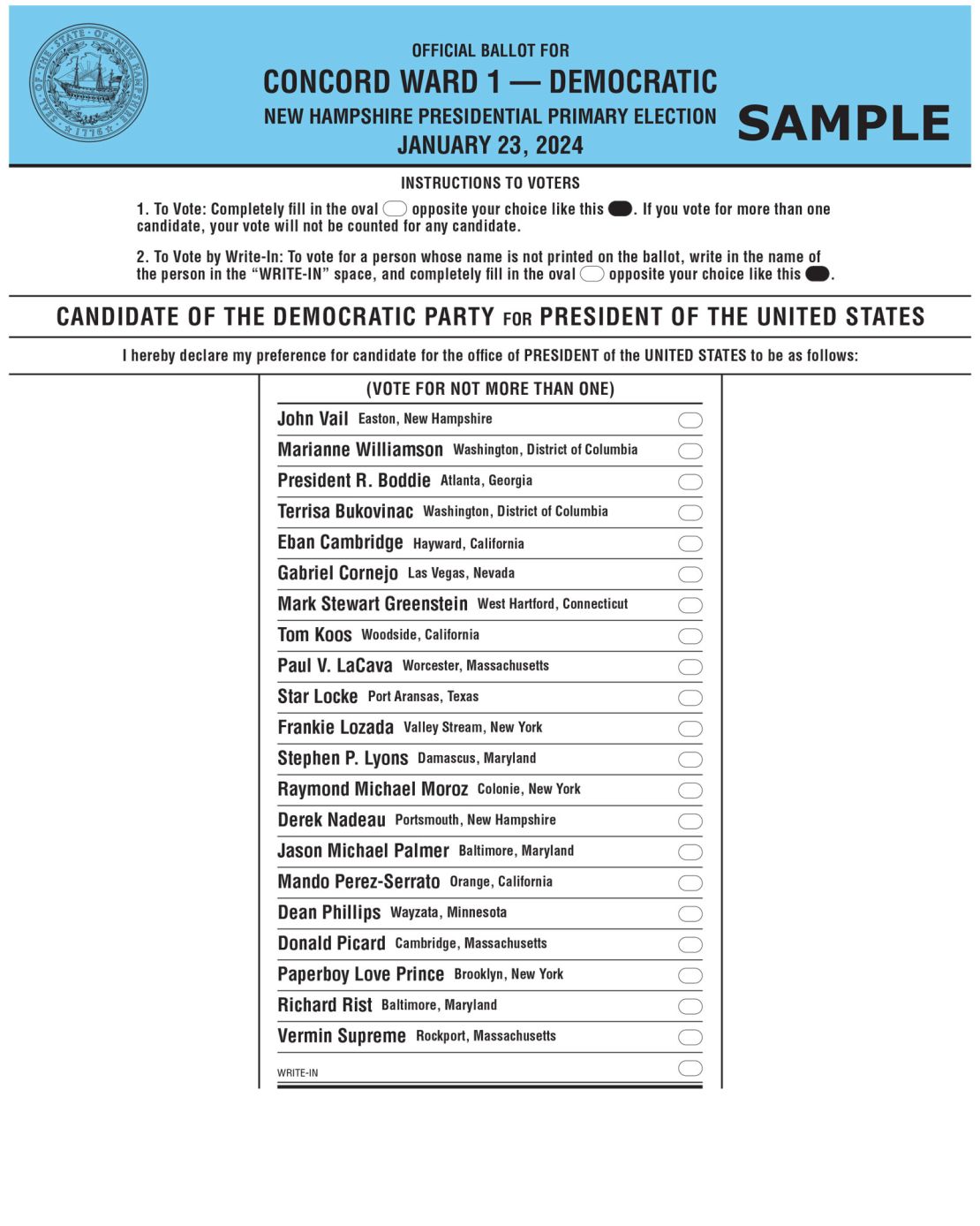

There are other options – for example, the author Marianne Williamson and Rep. Dean Phillips of Minnesota have gotten some attention. In all, there are 21 names on the Democratic ballot in New Hampshire this year. There is also a space for writing in a name at the bottom.

On the Republican side, multiple candidates who have suspended their campaigns – including former Vice President Mike Pence, former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie and Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina – are among the two dozen options on the ballot. Similar to the Democratic ballot, there’s also a space at the bottom for a write-in candidate.

Could Biden still win the New Hampshire primary?

There is an organized write-in effort encouraging primary voters to write Biden’s name on ballots.

But regardless of who wins, no delegates will be awarded based on the results of the contest because it violates the Democratic Party’s scheduling rules. The national party changed the nominating schedule to make South Carolina’s contest the first primary and is penalizing New Hampshire Democrats for not delaying theirs. While New Hampshire has a long-standing state rule requiring its primary to take place first, Granite State Democrats have chosen to stick with the state-run primary instead of trying to schedule a separate vote that would comply with DNC rules (as Iowa Democrats did).

The national party’s rules panel has called the contest “meaningless,” which led to New Hampshire’s Republican attorney general accusing the DNC of voter suppression.

How long has the New Hampshire primary been a thing?

Primaries are a relatively recent addition to the American democratic experiment.

New Hampshire was among a wave of states, led by Oregon in 1910, to give voters a say in the process with party primaries. Back then, primary voters elected delegates to national conventions. New Hampshire started conducting its presidential preference primary before other states in 1920, according to the state historical society.

Delegates still do technically pick the party’s nominee, but New Hampshire primary voters did not begin voting directly for presidential candidates until 1952.

The first direct primaries had an immediate impact. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower was still on active duty in the military and was not even a declared candidate when his name was put on the Republican ballot in New Hampshire in 1952. He went on to win the White House.

That same year, then-President Harry Truman, although an incumbent, suffered an unexpected loss in New Hampshire to then-Sen. Estes Kefauver and quickly dropped out of the race.

Similarly, in 1968, then-President Lyndon B. Johnson decided to end his campaign for reelection after only barely winning the New Hampshire primary. The second-place finisher, then-Sen. Eugene McCarthy, who opposed the war in Vietnam, was passed over for the nomination at the Democratic National Convention by party delegates who preferred then-Vice President Hubert Humphrey.

Violence broke out in Chicago around the Democratic convention that summer, leading to more efforts to democratize the primary process.

This story has been updated with additional information.