Editor’s Note: A version of this story appears in CNN’s Meanwhile in the Middle East newsletter, a three-times-a-week look inside the region’s biggest stories. Sign up here.

Israel is appearing before the International Court of Justice in a high stakes case that could change the course of the brutal war in Gaza.

It is an unprecedented case. Experts say it is the first time that the Jewish state is being tried under the United Nations’ Genocide Convention, which was drawn up after the Second World War in light of the atrocities committed against the Jewish people during the Holocaust.

The South African government, a successor to the apartheid regime that was made a pariah on the international stage three decades ago, brought the case against Israel, accusing it of being in breach of its obligations under the convention in its war on Hamas in Gaza.

Israel has firmly rejected the claim, with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu calling it a “false accusation.”

Israeli President Isaac Herzog said on Tuesday that his country will present a case “using self-defense” to show that it is doing its “utmost” under “extremely complicated circumstances” to avert civilian casualties in Gaza.

Eliav Lieblich, a professor of international law at Tel Aviv University, told CNN the case is significant politically and legally. “An allegation of genocide is the gravest international legal allegation that can be made against a state,” he said.

Here’s what we know about this case.

What is South Africa saying?

South Africa has taken Israel to the ICJ, also known as the World Court, on claims that it is committing genocide against Palestinians in Gaza and failing to prevent genocide.

On the first of two days of hearings, South Africa on Thursday told the court that Israel’s leadership had “declared their genocidal intent” in public comments surrounding the war, and that the actions of its military showed a “pattern of genocidal conduct.”

South Africa’s representatives argued that “the publicly available evidence of the scale of the destruction resulting from the bombardment of Gaza, and the deliberate restriction of food, water, medicines and electricity available to the population of Gaza, demonstrates that the government of Israel… is intent on destroying the Palestinians in Gaza as a group.”

“The acts in question include killing Palestinians in Gaza, causing them serious bodily and mental harm, and inflicting on them conditions of life calculated to bring about their physical destruction,” South Africa added in its 84-page filing to the court.

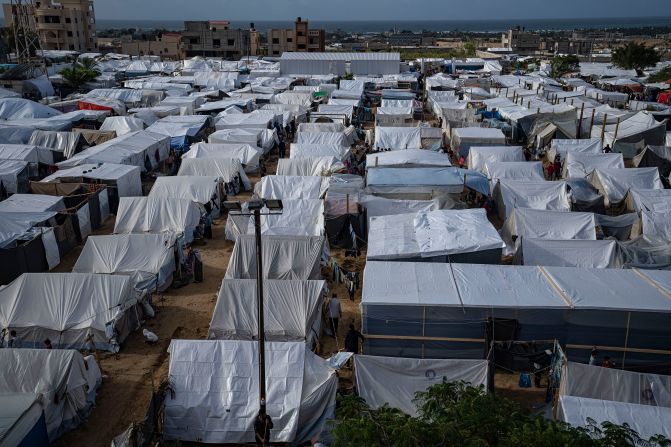

More than 23,000 people have been killed in Gaza since October 7, according to the Hamas-run Ministry of Health in Gaza.

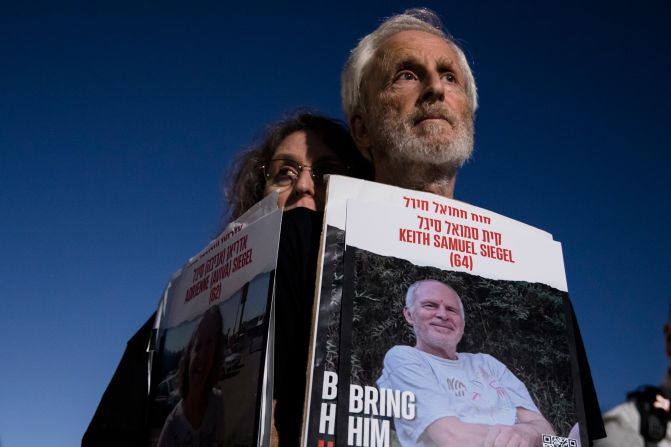

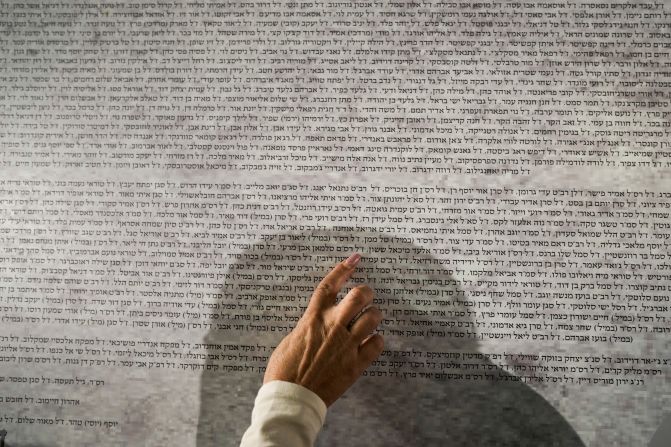

In pictures: Israel at war with Hamas

The United Nations defines genocide as an act “committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.”

The UN says that it was developed “partly in response to the Nazi policies of systematic murder of Jewish people during the Holocaust.”

In eight pages, the filing at the ICJ details what South Africa describes as “expressions of genocidal intent” by Israeli leaders, including Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and members of his cabinet.

South Africa has also asked the court to issue “provisional measures” ordering Israel to stop its war in Gaza, which it said was “necessary in this case to protect against further, severe and irreparable harm to the rights of the Palestinian people.” A provisional measure is a temporary order to halt actions, or an injunction, pending a final ruling.

The Organization of Islamic Cooperation, a grouping of 57 Muslim countries, as well as Jordan, Turkey and Malaysia have so far backed the case.

What is the International Court of Justice?

The ICJ is based in The Hague in the Netherlands and was set up in June 1945 by the Charter of the United Nations.

The court tries governments while the International Criminal Court, also in The Hague, prosecutes individuals. Israel doesn’t recognize the ICC so the court has no jurisdiction over it. Israel however is a signatory to the Genocide Convention, which gives the ICJ jurisdiction over it.

Member states of the UN and those who have accepted the ICJ’s jurisdiction can present cases. The court accepts cases in which the states involved have each accepted its jurisdiction. The ICJ is composed of 15 judges who serve nine-year terms. Current judges are from the US, Russia, China, Slovakia, Morocco, Lebanon, India, France, Somalia, Jamaica, Japan, Germany, Australia, Uganda and Brazil. Five seats come up for election every three years, with no consecutive term limit.

Four new judges will take their seats in February, one of whom is South Africa’s Dire Tladi.

Ad-hoc judges can be appointed by parties in contentious cases (between two states) – in this instance Israel and South Africa – bringing the number of judges in the case to 17. South Africa has appointed Dikgang Moseneke, the country’s former deputy chief justice, and Israel has named Aharon Barak, ex-president of the country’s Supreme Court.

Experts say a final ruling could take years.

How has Israel responded?

Israel has called the case a “blood libel” by South Africa, a thinly veiled accusation of antisemitism, and Netanyahu has in turn said that it is Hamas that has committed genocide, adding the Israeli military is acting in “the most moral way” and “does everything to avoid harming civilians.”

“And I ask: where were you, South Africa, and the rest of those who slander us, where were you when millions were murdered and displaced from their homes in Syria, Yemen and other arenas. You weren’t there,” the prime minister said.

Israel will nonetheless appear before the court.

That’s because it is a signatory to the UN’s 1948 Genocide Convention, which was drafted in the aftermath of the Holocaust. The treaty gives the ICJ the authority to adjudicate in cases, which can be brought by parties not directly affected by the alleged genocide in question.

“Since the court clearly has jurisdiction, it would be strange if Israel would simply not appear,” said Lieblich. “Also, genocide is a grave allegation, and states usually want to make their case.”

The Israeli public’s view of the case reflects the political disagreements in the country, Lieblich said. “Some view the proceedings as just another case of international bias against Israel. Many others are angry because they think that the case was only made possible because of irresponsible statements by far-right politicians, that in their views don’t represent actual policy.”

But he said that few in the Israeli mainstream are willing to accept the genocide allegations. “They mostly view the war as one of self-defense against Hamas, which due to the latter’s tactics result in wide but unintended harm to civilians.”

Polls show that Israelis overwhelmingly support the war.

Citing an Israeli diplomatic cable, Axios reported that Israel has mobilized its diplomats to lobby host nations to back its position and create international pressure against the case. Its “strategic goal,” it said, is for the court to reject the request for an injunction, refrain from accusing Israel of committing genocide, and acknowledge that it is operating according to international law.

“A ruling by the court could have significant potential implications that are not only in the legal world but have practical bilateral, multilateral, economic, security ramifications,” Axios cited the cable as saying.

Israeli government spokesperson Eylon Levy said Pretoria is “criminally complicit with Hamas’ campaign of genocide against our people.”

He also accused it of double standards, and backing former Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, who faces a warrant issued by the ICC.

“How tragic that the rainbow nation that prides itself on fighting racism will be fighting pro bono for anti-Jewish racists,” he said in a January 2 speech posted on X. “We assure South Africa’s leaders: History will judge you. And it will judge you without mercy.”

Lieblich said South Africa appears to be positioning itself in opposition to the US’ dominance in the international order.

“While it pursues the case against Israel, South Africa has criticized the ICC’s arrest warrant against Vladimir Putin, and has also refrained in the past from arresting Omar al-Bashir,” he said. “So, there is a clear international statement here. South Africa has been very vocal about what it views (as) Western ‘double standards’ and this case is a part of that campaign.”

Why is this case significant?

While the ICJ has ruled against Israel in the past, it did so through non-binding “advisory opinions” that are requested by UN bodies such as the General Assembly.

This is the first time Israel is being sued in the ICJ in what is known as a “contentious case,” where states directly raise cases against each other.

In 2004, the ICJ issued an advisory opinion declaring Israel’s separation barrier in the occupied West Bank to be in violation of international law, and called for it to be torn down. Israel ignored that decision.

If the ICJ eventually rules that Israel is directly responsible for genocide, it will be the first time it has found a state has commited genocide, experts said.

“This would be a significant precedent first and foremost because the ICJ never ruled, so far, that a state actually committed genocide,” Lieblich said. “The farthest it went was to rule that Serbia failed to prevent genocide by militias in Srebrenica. In this sense, such a ruling would be legally uncharted territory.”

While no state has been found to be directly responsible for genocide by the court, both Myanmar and Russia have faced provisional measures in genocide cases in recent years.

All ICJ judgements are final, without appeal and binding.

But the ICJ can’t guarantee compliance. In March 2022, for example, the court ordered Russia to immediately halt its military campaign in Ukraine. Kyiv, which brought the case, disputed the grounds for Russia’s invasion, and asked for emergency measures against Russia to halt the violence before the case was heard in full.

What happens if the court orders Israel to halt the war?

Israel is set to appear in public hearings before the court on Friday to contest South Africa’s genocide accusations.

A ruling on genocide could take years to prove, but the injunction on the Gaza war that Pretoria has asked the ICJ for could come much sooner.

Daniel Machover, a London-based lawyer and international justice expert, told CNN that a provisional measure should be a quick decision that would be taken before there is a final ruling on genocide.

South Africa, he said, only needs to demonstrate that it has standing to bring the case, has acted on its duty to prevent genocide, that there is a “plausible legal argument” that violations of the Genocide Convention are or may be taking place, and that there is a real and imminent risk that irreparable prejudice will be caused to Gaza residents before the court gives its final decision, such that the court needs to order Israel to stop the war.

Francis Boyle, an American human rights lawyer who won two requests at the ICJ under the Genocide Convention against Yugoslavia on behalf of Bosnia and Herzegovina, told Democracy Now that based on his review of the documents submitted by South Africa, he believes Pretoria will indeed win “an order against Israel to cease and desist from committing all acts of genocide against the Palestinians.”

Boyle, based on his experience in the Bosnian case, said the order could come within a week of this week’s hearings.

Lieblich doubts that Israel would cease the fighting altogether should the court issue an injunction on the war. Instead, it could attack the legitimacy of the court and its judges, “considering that some of them are from states that don’t recognize Israel.” It would also matter whether the decision is unanimous, he added.

“The consequences of non-compliance might range from reputational harm and political pressure to sanctions and other measures by third states or further resolutions in the UN,” he said. “The key for Israel would probably be how its key allies would act in such a case.”

He added that while the threshold for an injunction is relatively low, in the main case, proving genocide requires two elements: proof that certain unlawful acts were committed, and that these acts were committed with specific intent to destroy a certain group.

“In past ICJ cases the court required a high threshold to prove such allegations,” he said. “Here the challenge for South Africa would be to prove that statements by some Israeli officials actually reflect the state’s ‘intent’ as a whole, and also that Israel’s actions on the ground were both unlawful and actually tied to an intent to destroy the group as such.”

Could a ruling have implications outside Israel?

The fallout of an ICJ ruling could spread beyond Israel, according to experts. It would not only embarrass Israel’s closest ally, the US, but could also deem Washington complicit in the alleged violation of the Genocide Convention.

“Even though the South African application focuses on Israel, it has huge implications for the United States, especially President Joe Biden and his principal lieutenants,” wrote John Mearsheimer, an American political scientist.

“Why? Because there is little doubt that the Biden administration is complicitous” in Israel’s war, he said.

Biden has acknowledged that Israel is carrying out “indiscriminate” bombing in Gaza, but he has also vowed to protect the country. The US has bypassed Congress twice to sell military equipment to Israel during the war.

“Leaving aside the legal implications of his behavior, Biden’s name – and America’s name – will be forever associated with what is likely to become one of the textbook cases of attempted genocide,” Mearsheimer wrote.

Even if Israel ignores an order by the ICJ, there will be a legal obligation among other signatories to comply, said Machover. “So, anyone assisting Israel at that point will be in breach of that order.”

“We could have worldwide litigation if states don’t stop assisting Israel… there will be legal ripples across the world” he said.

The case could also have an impact on the Israeli public, Machover said. He believes that a significant number of Israelis “have not looked in the mirror” and lack awareness of the real impact of the war on Palestinians in Gaza.

The ICJ case, he hopes, would prompt the Israeli public to engage in “some sort of self-reflection.”