Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Huge fossilized bones that emerged from slate quarries in England’s Oxfordshire beginning in the late 1600s were immediately puzzling.

In a world where evolution and extinction were unknown concepts, the experts of the day cast around for an explanation. Perhaps, they thought, they belonged to a Roman war elephant or a giant human.

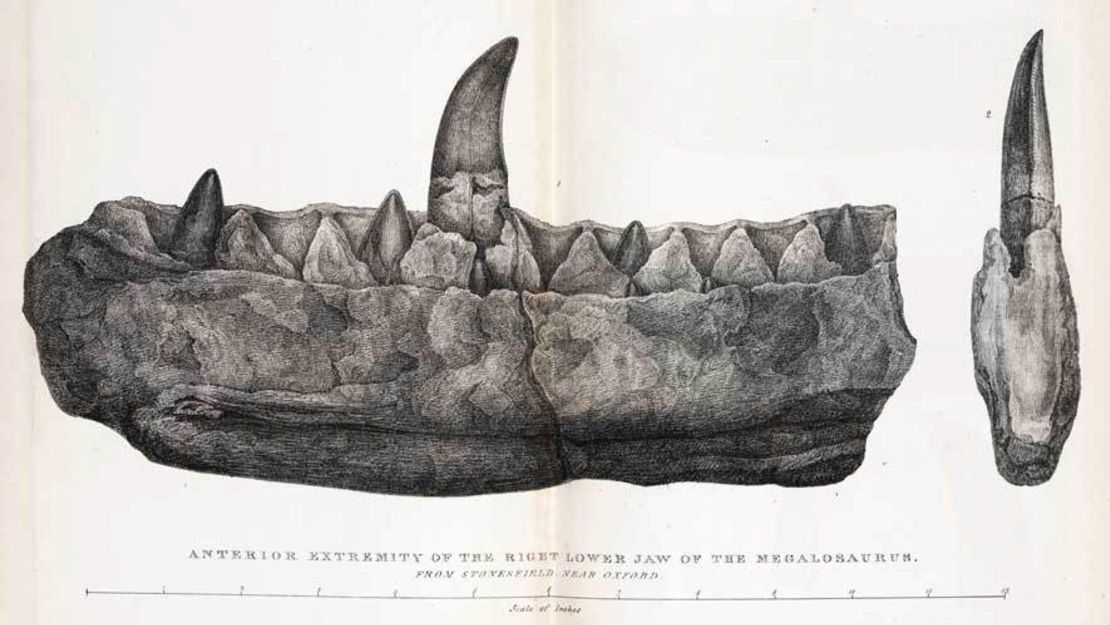

It wasn’t until 1824 that William Buckland, Oxford University’s first professor of geology, described and named the first known dinosaur, based on a lower jaw, vertebrae and limb bones found in those local quarries. The largest thigh bone was 2 feet, 9 inches long and nearly 10 inches in circumference.

Buckland named the creature the bones belonged to Megalosaurus, or great lizard, in a scientific paper that he presented to London’s newly formed Geological Society on February 20, 1824. From the shape of its teeth, he believed it was a carnivore more than 40 feet (12 meters) long with “the bulk of an elephant.” Buckland thought it was likely amphibious, living partially in land and water.

“In some ways he got a lot right. This was a group of extinct giant reptilian creatures.

This was a radical idea,” said Steve Brusatte, a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh and author of “The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of Their Lost World.”

“We all grew up watching dinosaur cartoons and watching ‘Jurassic Park,’ with dinosaurs on our lunchbox and toys. But imagine a world where the word dinosaur doesn’t exist, where the concept of a dinosaur doesn’t exist, and you were the first people that realize this simply by looking at a few large bones from the earth.”

The word dinosaur didn’t come into existence until 20 years later, coined by anatomist Richard Owen, founder of the Natural History Museum in London, based on shared characteristics he identified in his studies of Megalosaurus and two other dinosaurs, Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus, which were first described in 1825 and 1833, respectively.

The Megalosaurus paper cemented Buckland’s professional reputation in the new field of geology, but its significance as the first scientific description of a dinosaur was only apparent in retrospect.

At the time, Megalosaurus was eclipsed in the public imagination by the discovery of complete fossils of giant marine reptiles such as the ichthyosaur and plesiosaur collected by paleontologist Mary Anning on England’s Dorset Coast. No complete skeleton of Megalosaurus has been found.

But Megalosaurus did make its impact on popular culture. Charles Dickens, who was friends with Owen, imagined meeting a Megalosaurus on the muddy streets of London in the opening of his 1852 novel, “Bleak House.”

It was also one of three model dinosaurs to go on display at London’s Crystal Palace in 1854, home to the world’s first dinosaur park. It’s still there today. While its head shape is largely correct, today we know that it was about 6 meters (about 20 feet) long and walked on two legs, not four.

Who was Buckland?

How Buckland developed his expertise as a geologist isn’t clear.

An ambitious and charismatic scholar, he read classics and theology at Oxford, graduating in 1804, and took a wide range of classes, including in anatomy, said Susan Newell, a historian and associate researcher at the University of Oxford Museum of Natural History. He was also in contact with other celebrated natural scientists of the time such as George Cuvier in France, who was famous for his work comparing living animals with fossils.

“(Buckland) was the first person who really started to think well, what is going on with all of these weird fossils coming up, just up the road in this quarry in Oxford, and he started paying local quarrymen to find (fossils and) … keep stuff for him,” Newell said.

“He started to piece together the jigsaw.”

A year after his Megalosaurus paper was published, Buckland married his unofficial assistant, Mary Morland, who was a talented naturalist in her own right and the artist of the illustrations of Megalosaurus fossils that appeared in the groundbreaking paper.

Later in his career, Buckland recognized that most of the United Kingdom had once been covered in ice sheets after a trip to Switzerland, understanding that a period of glaciation had shaped the British landscape rather than a biblical flood.

Newell said Buckland’s scientific career ended prematurely, with him succumbing to some kind of mental breakdown that stopped him from teaching. He died in 1856 in an asylum in London.

What we’ve learned

For paleontologists, the 200-year anniversary of the first scientific naming of a dinosaur is an opportunity to take stock and look back at what the field has learned over the past two centuries.

Defined by their disappearance, dinosaurs were once thought to be evolutionary failures. In fact, dinosaurs survived and thrived for 165 million years — far longer than the roughly 300,000 years that modern humans have so far roamed the planet.

Today, around 1,000 species of dinosaurs have been named. And there are about 50 new dinosaur species discovered each year, according to Brusatte.

“Really, the science is still in the discovery phase. Yes, it’s 200 years old now, but we’ve only found a tiny fraction of the dinosaurs that have ever lived,” Brusatte said. “Birds today are the descendants of dinosaurs. There (are) over 10,000 species of birds that live just right now. And of course, dinosaurs lived for well over 150 million years. So do the math. There were probably thousands, if not millions, of different species of dinosaurs.”

In the 1990s, fossils unearthed in China definitively revealed that dinosaurs had feathers, confirming a long-held theory that they are the direct ancestors of the birds that flap around in backyards.

It’s not just amazing fossil discoveries that make the present a golden age of paleontology. New technology such as CT scanning and computational methods allow paleontologists to reconstruct and understand dinosaurs in far greater detail.

For example, in some feathered fossils, tiny structures called melanosomes that once contained pigment are preserved. By comparing the melanosomes with those of living birds, scientists can tell the possible original colors of the feathers.

There is still a lot to learn. It’s not completely clear how and why dinosaurs got quite so big, nor is it really known what noises the creatures might have made.

“I think it’s almost impossible for us to think back to a world where people did not know dinosaurs,” Brusatte said.

“However, there’s going to be things in the future where people will say how in 2024 did we not know that. (This anniversary) should give us a bit of perspective.”

London’s Natural History Museum and The Geological Society will hold special events in 2024 to mark the 200th anniversary of the naming of the first dinosaur.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly named George Cuvier. It has been updated.