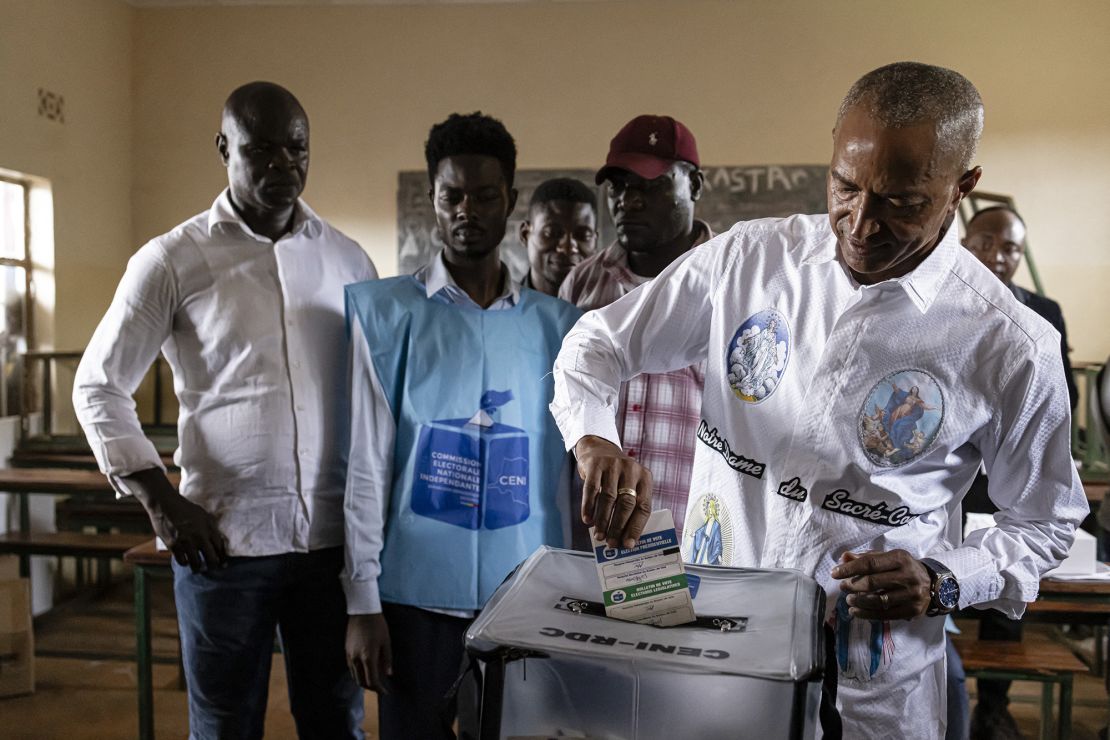

Democratic Republic of Congo was holding presidential and legislative elections on Wednesday after a chaotic campaign marred by opposition allegations of fraud, electoral violence, and logistical setbacks that could prevent many from voting.

At stake is not just the legitimacy of the next administration. DRC election disputes often spark violent unrest with potentially far-reaching consequences. DRC is the world’s third largest copper producer, and the top producer of

cobalt, a battery component needed for the green transition.

Delays were reported in several towns in DRC’s rebel-plagued east and in the capital Kinshasa, voting materials had not arrived at polling stations and voter lists were not published.

“It is a total chaos,” said presidential candidate Martin Fayulu, runner up in the disputed 2018 presidential election.

Fayulu said that while the vote was well organized in the upmarket Gombe district in the capital where he voted, it was not the case in the rest of the country.

“If all the people don’t vote in all the polling stations indicated by the CENI (national election commission), we won’t accept these elections,” Fayulu warned, adding that he would be at the forefront of the protest.

In the eastern cities of Goma and Beni, some people struggled to find their names on voter lists, which were only made available at their polling stations on Wednesday morning, according to Reuters witnesses.

In Bunia, also in eastern Congo, security forces fired warning shots to disperse protesters after a voting center was vandalized and kits destroyed, a Reuters reporter said.

A provincial election commission official told journalists that people displaced by violence in the region had protested because they wanted to vote in their home towns.

For months, Congo’s national election commission has insisted it would deliver a free and fair vote as promised across Africa’s second-largest country, even as independent observers and critics flag irregularities they say will jeopardize the legitimacy of the results.

About 44 million Congolese are registered to take part in the voting, which also includes regional ballots.

As voting day neared, the authorities sought extra helicopters, raising concerns about the commission’s ability to open polling stations in areas otherwise unreachable due to bad roads or a lack of security.

Full provisional results are expected by December 31.

Electoral transparency

President Felix Tshisekedi is competing against 18 opposition challengers in the hope of a second term running the mineral-rich yet poverty-stricken nation.

“I have asked you to give me strength to continue the work that we have started,” Tshisekedi said in his final rally on Monday, promising to expand a free education policy if elected.

Opposition candidates have wooed voters with pledges to bring stability, peace, and the economic development they say was absent from Tshisekedi’s first term.

They and religious and civil society electoral observers have sounded the alarm about electoral transparency, highlighting issues including the voter list and illegible ID cards.

“It is evident that the greatest electoral fraud of the century is taking place,” Nobel Laureate and opposition candidate Denis Mukwege said on Monday. The election commission has repeatedly rejected the opposition’s allegations of fraud.

The election will be decided in a single round, requiring a simple majority of the vote to win. The final run-up to the vote has been particularly fraught.

Two parliamentary candidates were killed in separate incidents on Dec. 15 - part of a spate of election-related violence condemned by human rights groups and the European Union.

Ahead of election day in Kinshasa, some locals were not convinced their vote would count. “Every time we vote, we are disappointed, but if I had to vote, it would be for a change,” said 43-year-old Lucie Mpiana, who is unemployed.