Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

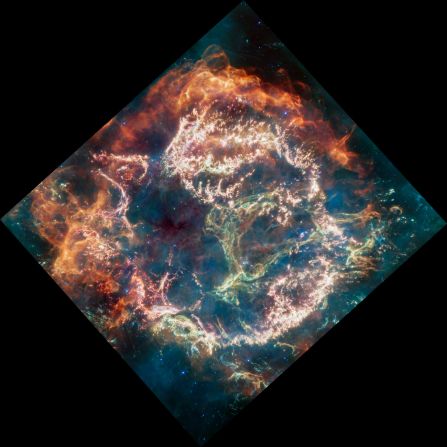

Thousands of years ago, a star in our galaxy violently exploded and created a glowing supernova remnant called Cassiopeia A that has intrigued scientists for decades.

Now, a new image captured by the James Webb Space Telescope has revealed the closest and most detailed look inside the exploded star, according to astronomers. Analyzing the image could help researchers better understand the processes that fuel these massive incendiary events.

The space observatory has also allowed astronomers to glimpse mysterious features that haven’t appeared in images taken of the remnant using telescopes like Hubble, Chandra or Spitzer or Webb’s other instruments.

The new image was shared on Monday by first lady Dr. Jill Biden as she debuted the first-ever digital White House Advent Calendar, which includes Webb’s new perspective of Cassiopeia A that seems to shine like a Christmas ornament.

“We’ve never had this kind of look at an exploded star before,” said astronomer Dan Milisavljevic, assistant professor of physics and astronomy at Purdue University, in a statement. “Supernovae are primary drivers of cosmological evolution. The energies, their chemical abundances — there is so much that depends on our understanding of supernovae. This is the closest look we’ve had at a supernova in our galaxy.”

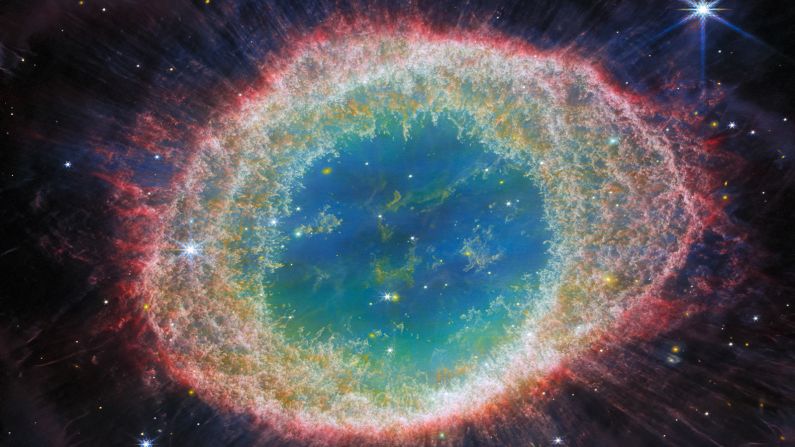

Swirls of gas and dust are all that remain of the star that went supernova 10,000 years ago. Cassiopeia A is located 11,000 light-years away in the Cassiopeia constellation. A light-year, equivalent to 5.88 trillion miles (9.46 trillion kilometers), is how far a beam of light travels in one year.

The light from Cassiopeia A first reached Earth about 340 years ago. As the youngest known supernova remnant in our galaxy, the celestial object has been studied by a multitude of ground- and space-based telescopes. The remnant stretches for about 10 light-years across, or 60 trillion miles (96.6 trillion kilometers).

Insights from Cas A, as the remnant is also known, allow scientists to learn more about the life cycle of stars.

Seeing Cas A in a new light

Astronomers used Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera, called NIRCam, to see the supernova remnant at different wavelengths of light than those used in previous observations. The image shows unprecedented details of the interaction between the expanding shell of material created by the supernova as it collides with the gas released by the star prior to the explosion.

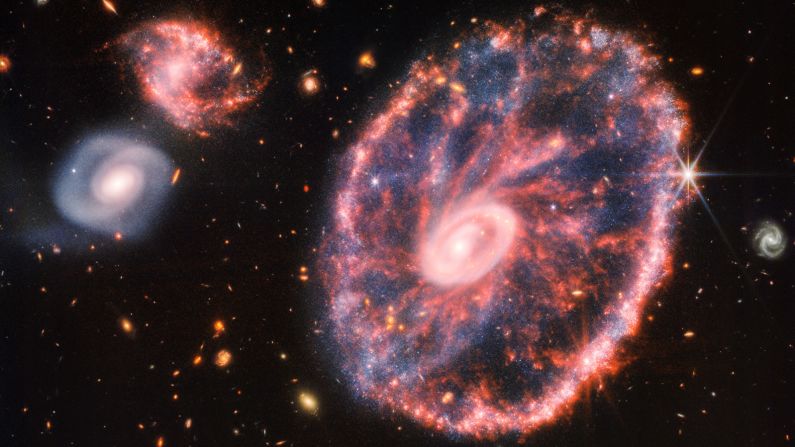

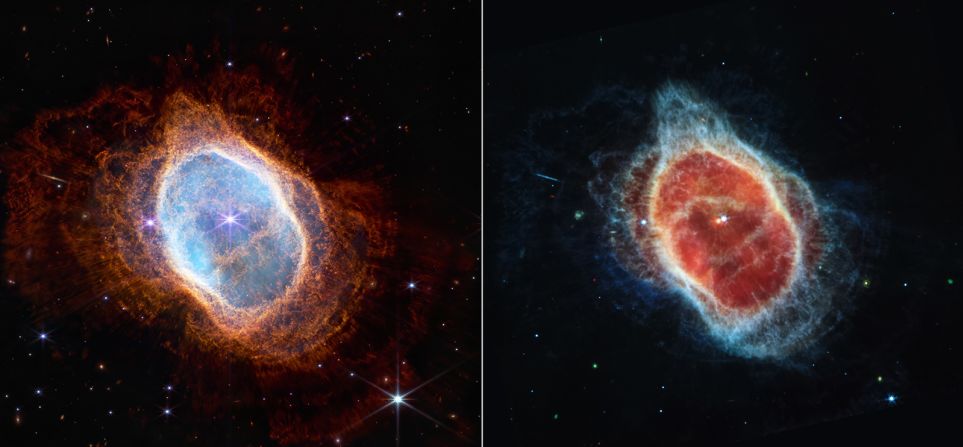

But the image looks completely different from one taken by Webb in April using the telescope’s Mid-Infrared Instrument, or MIRI. In each image, certain features stand out that are invisible in the other.

Webb observes the universe in wavelengths of infrared light, which is invisible to the human eye. As scientists process Webb’s data, the light captured by the telescope is translated into a spectrum of colors visible to humans.

The new NIRCam image is dominated by orange and light pink flashes of color within the supernova remnant’s inner shell. The colors correspond to gaseous knots of elements shed by the star, including oxygen, argon, neon and sulfur. Mixed within the gas are dust and molecules. Eventually, all of these ingredients will combine to form new stars and planets.

Studying the remnant allows scientists to reconstruct what happened during the supernova.

“With NIRCam’s resolution, we can now see how the dying star absolutely shattered when it exploded, leaving filaments akin to tiny shards of glass behind,” Milisavljevic said. “It’s really unbelievable after all these years studying Cas A to now resolve those details, which are providing us with transformational insight into how this star exploded.”

Webb’s dual perspectives

When comparing the NIRCam image with the MIRI image taken in April, the new perspective seems less colorful. The bright swirls of orange and red from the April image look smokier through NIRCam’s eyes, showing where the shock wave from the supernova crashed into surrounding material.

The white light in the NIRCam image is due to synchrotron radiation, which is created when charged particles accelerate and travel around magnetic field lines.

![This image provides a side-by-side comparison of supernova remnant Cassiopeia A (Cas A) as captured by the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope's NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) and MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument). At first glance, Webb's NIRCam image appears less colourful than the MIRI image. But this is only because the material from the object is emitting light at many different wavelengths The NIRCam image appears a bit sharper than the MIRI image because of its greater resolution. The outskirts of the main inner shell, which appeared as a deep orange and red in the MIRI image, look like smoke from a campfire in the NIRCam image. This marks where the supernova blast wave is ramming into surrounding circumstellar material. The dust in the circumstellar material is too cool to be detected directly at near-infrared wavelengths, but lights up in the mid-infrared. Also not seen in the near-infrared view is the loop of green light in the central cavity of Cas A that glowed in mid-infrared light, nicknamed the Green Monster by the research team. The circular holes visible in the MIRI image within the Green Monster, however, are faintly outlined in white and purple emission in the NIRCam image. [Image description: A comparison between two images, one on the left (labelled NIRCam), and on the right (labelled MIRI), separated by a white line. On the left, the image is of a roughly circular cloud of gas and dust with a complex structure. The inner shell is made of bright pink and orange filaments that look like tiny pieces of shattered glass. Around the exterior of the inner shell are curtains of wispy gas that look like campfire smoke. On the right is the same nebula seen in different light. The curtains of material outside the inner shell glow orange instead of white. The inner shell looks more mottled, and is a muted pink. At centre right, a greenish loop extends from the right side of the ring into the central cavity.]](https://media.cnn.com/api/v1/images/stellar/prod/231212105853-james-webb-space-telescope-cassiopeia-a-split.jpg?q=w_1110,c_fill)

A key feature missing from the NIRCam view is the “Green Monster” from the MIRI image, or a circle of green light in the remnant’s center, that has puzzled and challenged astronomers.

But new details can be seen in the near-infrared image that point to circular holes wreathed in white and purple, designating charged particles of debris that shape the gas shed by the star before it exploded.

Another new feature in the NIRCam image is a blob nicknamed Baby Cas A that can be seen in the bottom right corner, which looks like an offspring of the larger supernova remnant and is located 170 light-years behind Cassiopeia A.

Baby Cas A is actually a feature called a light echo, where the supernova’s light interacted with dust and caused it to heat up. The dust continues to glow as it cools over time.

“It’s staggering,” said Milisavljevic, who led a project team that contributed to the new image. “Some features have popped up that are completely new — that will change the way we think about stellar life cycles.”