Rapid melting of West Antarctica’s ice shelves may now be unavoidable as human-caused global warming accelerates, with potentially devastating implications for sea level rise around the world, new research has found.

Even if the world meets ambitious targets to limit global heating, West Antarctica will experience substantial ocean warming and ice shelf melting, according to the new study published Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change.

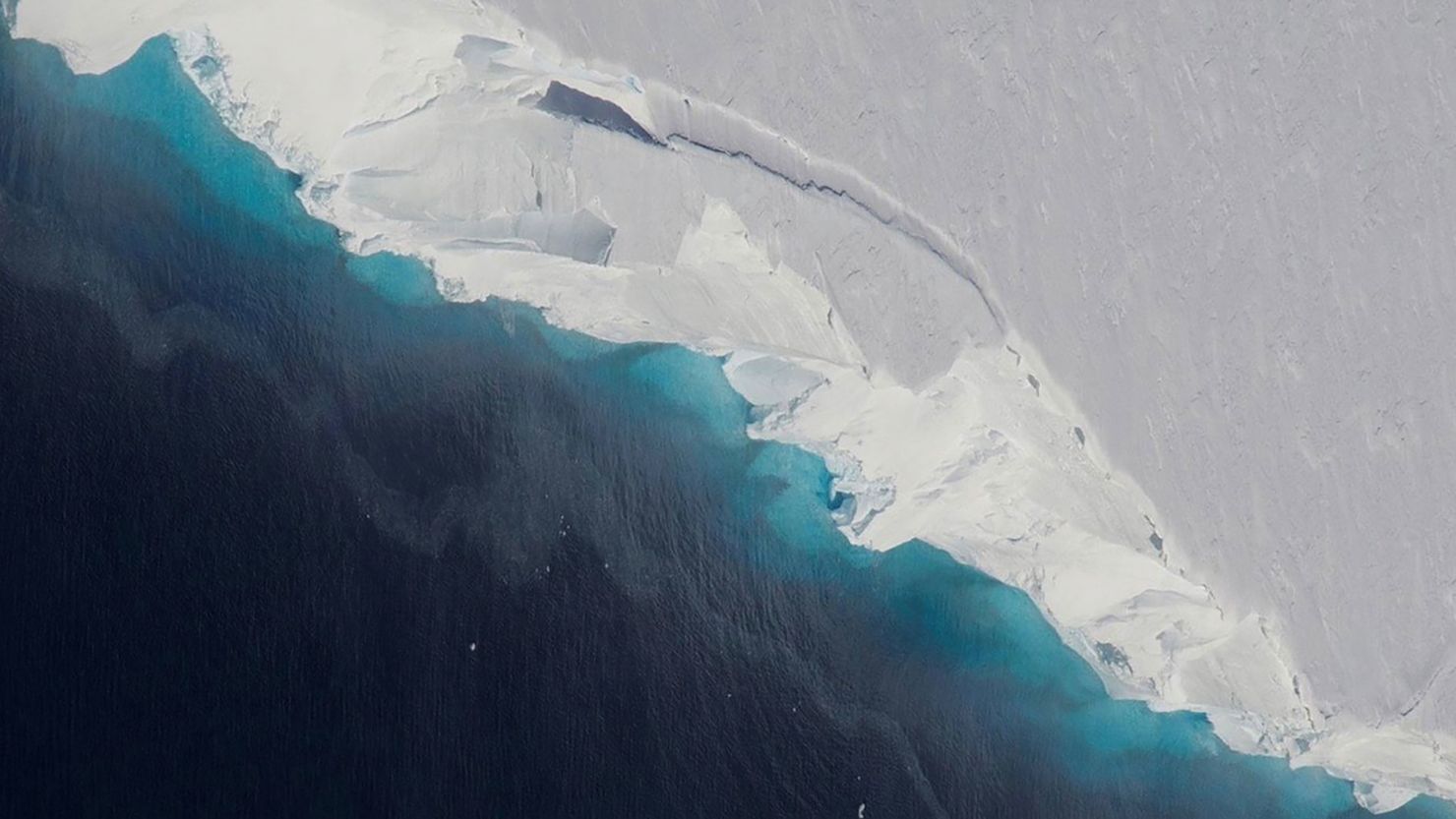

Ice shelves are tongues of ice that jut out into the ocean at the end of glaciers. They act like buttresses, helping hold ice back on the land, slowing its flow into the sea and providing an important defense against sea level rise. As ice shelves melt, they thin and lose their buttressing ability.

While there has been growing evidence ice loss in West Antarctica may be irreversible, there has been uncertainty about how much can be prevented through climate policies.

The researchers looked at “basal melting,” when warm ocean currents melt the ice from beneath. They analyzed the rate of ocean warming and ice shelf melting under different climate change scenarios. These ranged from the ambitious, where the world manages to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, to the worst-case, where humans burn large amounts of planet-heating fossil fuels.

They found if the world limits temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius, which it is not on track to do, climate change could still cause the ocean to warm at three times the historical rate.

Even significantly cutting planet-heating pollution now will have “limited power” to prevent warmer oceans from triggering the collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet, the report found.

“It appears that we may have lost control of the West Antarctic ice melting over the 21st century,” said Kaitlin Naughten, an ocean modeler with the British Antarctic Survey and lead author of the study.

West Antarctica is already the continent’s largest contributor to global sea level rise and has enough ice to raise sea levels by an average of 5.3 meters, or more than 17 feet. It’s home to the Thwaites Glacier, also known as the “Doomsday glacier,” because its collapse could raise sea levels by several feet, forcing coastal communities and low-lying island nations to either build around sea level rise or abandon these places, Naughten said.

While the study focused on ice shelf melting and did not directly quantify the impacts on sea level rise, “we have every reason to expect that sea level rise would increase as a result, as West Antarctica speeds up this loss of ice into the ocean,” Naughten said.

Ted Scambos, a glaciologist at the University of Colorado Boulder who was not involved with the study, said the findings are “sobering.” They build on existing research that paints an alarming picture of what’s happening to the planet’s southernmost continent, he told CNN.

“The thing that’s depressing is the committed nature of sea level rise, particularly for the next century,” Scambos told CNN. “People who are alive today are going to see a significant increase in the rate of sea level rise in all the coastal cities around the world.”

The only way to really stop the rapid ice melting, Scambos said, would be not just to cut levels of planet-heating pollution but also to “remove some that has already built up.” This will be “a real challenge,” he said.

Some scientists sounded a note of caution about the study. Tiago Segabinazzi Dotto, senior research scientist at the National Oceanography Centre in the UK, said it should be “treated carefully” as it is based on a single model.

However, its conclusions do agree with previous research in the region, he told the Science Media Center, giving “confidence that this study needs to be taken in consideration for policymakers.”

Naughten and her colleagues acknowledged their study has limits — predicting future rates of melting in West Antarctica is very complex and it’s impossible to account for every possible future outcome. But, looking at the range of scenarios, the report authors said they were confident the melting of ice shelves is now unavoidable.

“The question of doom and gloom is something I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about with this study, because how do you tell such a bad news story?” Naughten said.

“Conventional wisdom is supposed to give people hope, and I don’t see a lot of hope in this story,” she added, “but it’s what the science tells me and it’s what I have to communicate to the world.”

West Antarctic ice shelf melting is one impact of climate change “we are probably just going to have to adapt to and that very likely means some amount of sea level rise we cannot avoid,” Naughten said.

But although the outlook is dire, humanity cannot give up on slashing fossil fuel emissions, Naughten said. Devastating impacts can still be avoided in other parts of Antarctica and the rest of the world, she noted.