On a hot, sticky day in early October, 25-year-old Alesmar stood on a street corner in Manhattan holding her son’s hand.

Wearing a tank top, her dark hair bound up in a pink scrunchie, she did not want to share her last name. She said she arrived in New York at the end of April, after two months traveling by foot and bus from the port city of La Guaira, Venezuela, to the US border – a difficult journey marked by frequent setbacks.

Mexican regional officials kept forcing Alesmar and her kids back south, making Mexico the longest-lasting segment of their trip.

“It was especially hard in Mexico, where they grabbed us and sent us back,” she explained. Referring to Mexican states, she added, “State after state denied us permission to transit and sent us back in the direction we came from.”

Eventually, Alesmar made it to New York. She is still living in temporary housing in Manhattan and her two young sons, ages four and eight, are enrolled at nearby Public School 111, where they are learning English and adjusting to life in a new country.

“It’s a new place for them, because of the language, but they’re doing really well,” she said. “I want something better for them, since we cannot achieve anything in our country.”

Alesmar’s children are among dozens of new students at the elementary school that has long welcomed a diverse student body, with children hailing from places like Ukraine, China and Tibet. Some 56 percent are Hispanic.

More than 120,000 migrants have arrived in New York since the spring of 2022. Many live in temporary housing – often hotels serving as shelters – and many are seeking asylum. The surge has added nearly 30,000 children to the city’s public schools.

NYC Schools Chancellor David Banks has said new arrivals will get “the best” the city has to offer, and since about 120,000 families left New York public schools over the course of the Covid-19 pandemic, there is room for the newcomers.

In fact, P.S. 111 has not yet returned to its pre-pandemic population. Three new students enrolled the day CNN visited.

About 36 percent of the school’s roughly 400 students now live in temporary housing, compared to 10 to 20 percent of the student body in a typical year, according to Principal Edward Gilligan.

He says they are prepared for the influx. They faced challenges early on – more than a hundred students enrolled in just a few days in July 2022 and they had to hire new staff to deal with over-crowded classes.

“Coming in this year, people felt a lot more confident,” Gilligan said of the school’s staff. “A lot more prepared.”

The school has added about 75 new students this year, on top of its usual enrollment.

Migrants camping in New York City bring a crisis into focus

Increased funding

P.S. 111 now has three teachers handling English as a new language classes – one focusing just on kindergarten.

As a Title 1 school serving a high percentage of children from low-income families, it receives federal funding to help students meet state academic standards. It also provides backpacks to children who need them and helps parents find English classes. The school has always had a high number of new English learners and boasts other support staff like social workers, psychologists and physical therapists, Gilligan said. School staffers work closely with families of new arrivals to help connect them with health and immigration services.

The school also benefited from an increase in funding that’s provided based on the number of students in temporary housing. The biggest challenges are dealing with food insecurity, making sure families have access to vaccinations and getting kids up to grade level, Gilligan said.

A ‘sometimes difficult journey’

Students arrive at P.S. 111 with varying levels of education, sometimes having missed months of school.

“Almost universally, they come without any English,” said Jen Singer, an ENL teacher who has worked at the school for more than two decades. “But, also, they’ve come through a long and sometimes difficult journey and so they need a lot of loving and clothes and food and just to feel safe and secure.”

English learners are pulled out of the ordinary reading or writing class for 180 minutes a week of specialized instruction, but they learn math and other subjects alongside their English-speaking peers, with the help of the ENL teachers who modify their lessons when necessary.

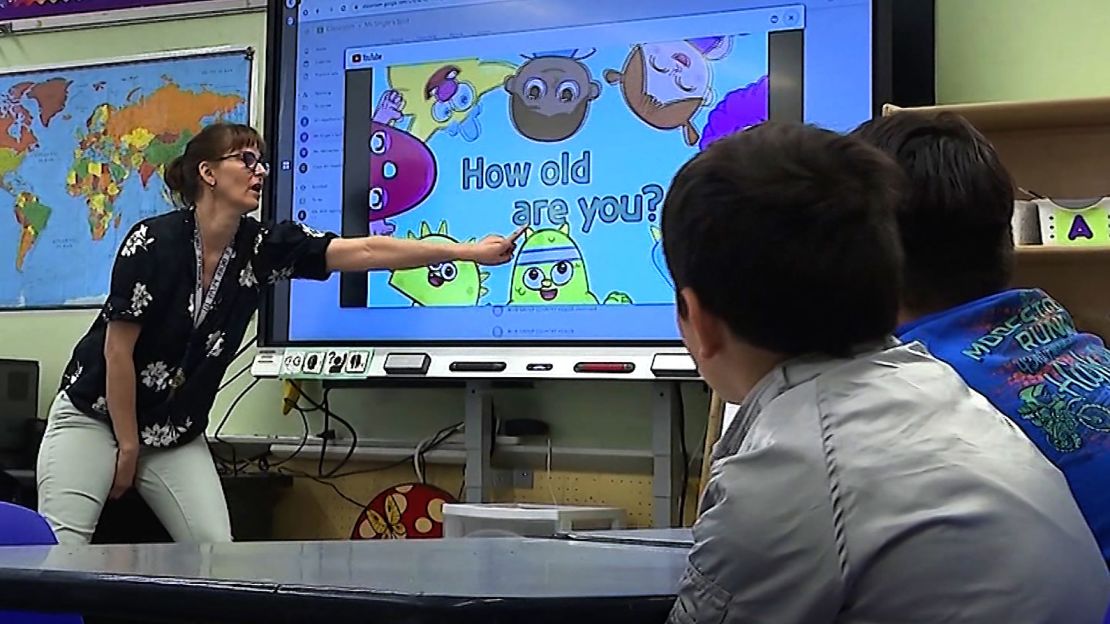

ENL classes are immersive. Singer spends time reading aloud to the children and teaching them new vocabulary. Repetition is key and while Singer speaks Spanish, she tries not to use it during class, often relying on pictures and video, while also sometimes acting things out.

“I want to set up the expectation that they can understand English and they can learn it and they can speak it,” she said.

Singer said it takes years to learn English – one to three years to learn it socially so students can talk about where they live and other conversational topics – and longer for academic subjects.

‘I have always liked to think big’

About four months before Alesmar arrived in New York from Venezuela, Diana Amezquita arrived from Bogota, Colombia. On a recent afternoon, she stood watching her children on the monkey bars at a playground on Manhattan’s west side. She came here with her partner and three children, but has struggled since her partner decided to return to their country.

“It’s very complicated, because many times we’re discriminated against when it comes to work because of the language. Because our English is not advanced,” she said. Still, she added, “I have and I see opportunities here.”

Her 7-year-old daughter and 9-year-old son are enrolled in a separate Manhattan elementary school a few blocks from P.S. 111. But she has big dreams for herself and her children. It starts with learning English so they can have better paying jobs and a better life.

Amezquita hopes to one day work in human resources as she did back home, but said working at a hotel and caring for her children have made it impossible to take English classes at the moment. Still, she is thankful to have made it to New York and has faith she can make a good life here.

“I have always liked to think big,” Amezquita said. “So I feel proud to be here with them.”