It is with a weird retrospective guilt that I have to admit: Hamas once saved me from a kidnapping in Gaza.

The militant group behind massacres and abductions, the slaughter of civilians, and the cynical endangerment of their own people, stopped an Islamist gang seconds before they were about to grab me from the Hotel Deira in northern Gaza in 2008.

With hushed efficiency, Hamas intelligence officers swarmed the hotel. No shots were fired.

The kidnap gang, diverted from its mission, blew up the nearby British Council offices in a fit of pique.

That was the old Hamas. Yes, a violent group with a history of terror tactics directed against Israelis, a long commitment to destroying the state of Israel (though not one of genocide against Jews or Israelis), but also a social movement of political Islam with a reputation in the Arab world for efficiency and probity.

Yet the Palestinian militant group was always cynical in its use of violence and in its perpetuation of a cult of martyrdom.

When, during the second Intifada in 2000, Israeli troops used live fire against armed militants as well as unarmed civilians across the Palestinian territories, Hamas unleashed waves of suicide bombers — and insisted on “celebrating” the deaths of Palestinian children as martyrs.

At a clandestine meeting in Khan Younis, southern Gaza, in early 2001, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin gasped and peeped. He spoke to me through an interpreter – the group’s only person who could decipher the sounds he made.

Wheelchair bound from youth, the founder of Hamas claimed that while “Israelis love life,” “we celebrate the greatest gift of martyrdom for our children. Every mother wants that for her child.”

A few weeks later the Israelis killed him.

But his group’s intense combination of victimhood and passion for martyrdom lived on. Indeed it deepened as Hamas took hold of Gaza and risked sacrificing its inhabitants to Israeli air raids and ground invasions — usually provoked by Hamas attacks.

Cycles of violence and peace had already characterized the Hamas approach, depending on which of its wings — military or civilian — prevailed.

One influential military figure in Hamas was always resolutely opposed to any kind of peace with what Hamas insists on calling the “Zionist Entity.”

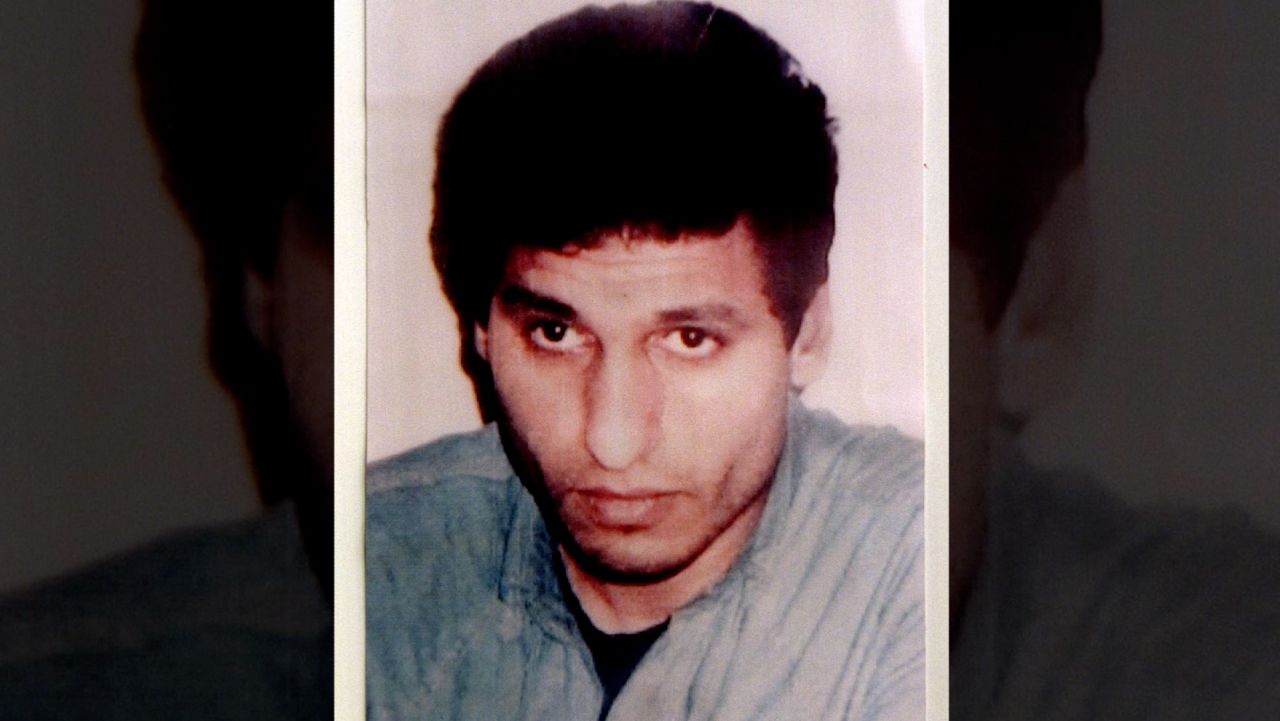

Mohammed Diab Ibrahim al-Masri, is known as El Deif (the Guest), because, for decades, he has stayed in different houses every night to avoid being tracked, and killed, by Israel. He’s now in charge of Hamas’ military wing, the Al Qassem Brigades.

Thought to have been born in the 1960s, El Deif is little known to ordinary Palestinians, according to Mkhaimar Abusada, professor of political science at Al Azah University in Gaza.

“He’s very much like a ghost to the majority of the Palestinians,” he said.

The Al Qassem Brigades were opposed to the peace process embraced by Yassir Arafat, then-leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization, and the 1993 Oslo Accords that were supposed to pave the way to a two-state solution of a new Palestine living in peace alongside Israel.

In 1996 El Deif, an accomplished bomb maker, was behind a wave of four suicide attacks that killed 65 people in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv and other outrages intended to derail the peace process.

As Hamas captured Gaza from rivals Fatah in 2007 (after winning the Palestinian elections the year before) Israel and Egypt tightened a noose around the enclave, which houses around 2 million people.

Hamas is seen by many Palestinians as the best alternative to rule by the Palestinian Authority (PA), which is dominated by Fatah and the larger Palestine Liberation Organization. The PA pays the wages for the public sector in Gaza, and this summer polls showed that support for the PA, which only rules on the West Bank, was nonetheless around 70% in Gaza.

Support for Hamas in Gaza has rarely tipped much past 50%. And on the ground, in private conversations, it’s been difficult to find people who are genuinely behind Hamas military campaigning. But few people are prepared to be openly critical and risk arrest.

Israel’s policies over the West Bank, where Jewish settlements, which are illegal under international law, spread steadily across the occupied territories, over access to the al Aqsa Mosque complex in Jerusalem, and the moribund efforts to achieve a viable two-state solution, meant Hamas was able to weaponize grievance. The movement has no shortage of volunteers in the crowded enclave everyone there calls the “biggest prison in the world.”

The tighter the Israeli and Egyptian control over Gaza’s borders – the more Hamas (and other groups) developed military means to fight back.

Chief among them is rockets. Primitive at first, the missiles have been improved and refined over years of help from Iran.

The Tehran theocracy, also dedicated to the eradication of the Jewish state, trained engineers, organized technology transfers and guided developments to create rockets capable of hitting Jerusalem and Tel Aviv.

Men like El Deif, the bomb makers and decision takers, were hunted by Israel.

In 2014, an air strike killed his wife and daughter. He lost part of an arm, a leg and his hearing. No doubt his hatred for Israel intensified then.

But his emotions were leavened with zealous cunning. And the first, and most important deception, was to transform the Israeli perception of Hamas.

In the last two years, Hamas, under El Deif’s guidance, worked to convince Israel that its focus was on domestic issues, on rebuilding Gaza, on securing work permits for people to seek employment in Israel, on building up its infrastructure.

“The Israelis have felt that, in the long run, that Hamas is known for these policies more than that there’s going to be a call for a military confrontation with Israel,” says Abusada, the Gazan professor.

All the while, though, Hamas was plotting a massive assault that would end any perception in Israel, and beyond, that the Islamic Resistance had lost its strategic mojo.

Key to this change, too, was another major figure in Hamas’ military wing, Yahya Sinwar. A former head of the Al Qassem brigades, he’s now the head of Hamas in Gaza.

He focused efforts on building relationships with foreign powers — notably Egypt and Iran.

Hamas’ attack on Israel last weekend represents the worst Israeli military setback since 1973. Back then Syria and Egypt launched a surprise assault on Israel over the Yom Kippur holiday. Initially successful, the Arabs were soon pushed back as Israel rallied.

Now Israel is massing troops on the borders with Gaza and in the north where it faces Iran-backed Hezbollah across the fence with Lebanon.

What will Hamas ultimately gain from its bloody gamble? Karim von Hippel, director of the London-based Royal United Services Institute, says “they may have been planning this for years and thinking through what they can do, because everything else they have tried, hasn’t worked.”

“But certainly this is not going to work either. I think this will spell the end of Hamas.”

That may be a zero-sum option that not even the shadowy El Deif had guessed at.

Additional reporting by CNN’s Lauren Kent.