Water levels on the Mississippi River are nearing historic lows for the second consecutive year, triggering a drinking water emergency in Louisiana as ocean water flows upstream, unimpeded by the river’s uncharacteristically weak flow.

With no substantial rain in the immediate forecast, levels are expected to drop to even more dire levels in the coming weeks, leading Louisiana’s governor to warn water woes there could stretch into January.

Water gauges across a nearly 400-mile expanse of the Mississippi River from the mouth of the Ohio River to Jackson, Mississippi, are at or below a critical level, according to data from NOAA and the US Geological Survey, signaling widespread disruption to residents and industry along the river.

All the gauges in the Memphis area are within the top five lowest levels on record, said Katie Dedeaux, a hydrologist for the National Weather Service in Memphis. Water levels for some gauges from southern Missouri to central Mississippi are expected to dip even further and fall below record levels by the middle of October.

Lower Mississippi River water levels are forecast to continue to drop through at least mid-to-late October, according to Dedeaux.

“We’re going to need a pretty significant period of wet weather across the basin,” Dedeaux told CNN, noting that this isn’t a situation where one heavy rain event can fix the problem. “It’s not going to be an overnight thing.”

This could spell trouble for the tens of thousands of people in four Louisiana parishes, including New Orleans, whose water is threatened by salty ocean water pushing northward into water systems.

In order to push the saltwater back, “10 inches of precipitation across the entire Mississippi Valley” is needed, according Col. Cullen Jones, commander of the Army Corps’ New Orleans office – relief that may not arrive until this winter.

A confluence of extremes

Water levels on the Mississippi River began to plummet in early September, well ahead of the October drop last year.

The consecutive nature of these droughts has prevented the river from being able to recharge, Dedeaux told CNN.

Meaningful rainfall was hard to come by for large swaths of the Mississippi River watershed over the summer due to a seemingly never-ending series of heat domes which fueled record-breaking temperatures and directed wet weather away from the southern and central US.

Heat-fueled exceptional drought, which is the highest level defined by the US Drought Monitor, is in place across nearly one-fifth of the lower Mississippi River region – the second-largest area recorded there since 1999. This summer was the hottest and the third-driest on record for Louisiana, where over 85% of the state is in severe or exceptional drought.

Portions of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Mississippi and Louisiana ended the summer with a rainfall deficit of 2 to 8 inches under what typically falls during the course of the season, according to data from NOAA. Some parts of Louisiana even missed out on 10 or more inches of typical rainfall over the summer.

The rainfall deficit at the southern end of the watershed can also be tied back in part to a lack of hurricane activity impacting the region the past two hurricane seasons. No tropical systems, which can dump large quantities of rain, have made landfall in Louisiana or Mississippi over the last two years.

So even though October and November are typically when the Mississippi River is at its lowest levels, all of these factors fueled significant rainfall deficits across the Mississippi watershed which sent levels dramatically lower than normal, Alexis Highman of the Lower Mississippi River Forecast Center told CNN.

When will water levels rebound?

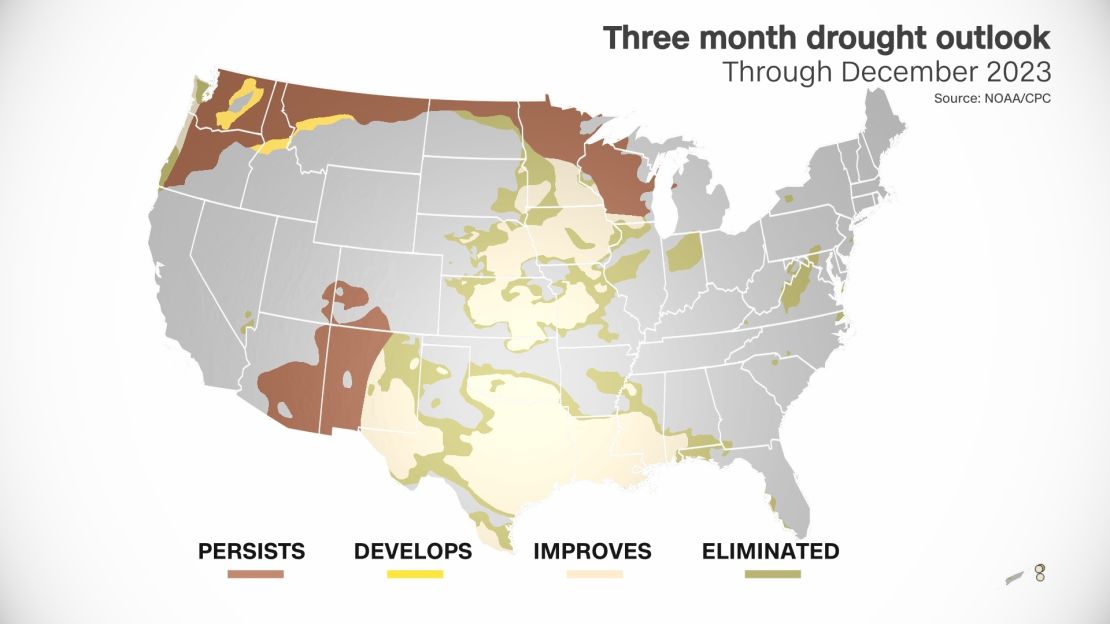

There are signs of relief in the longterm. A drought outlook recently released by NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center forecasts improvement, but not elimination, of drought conditions by the end of the year across the Mississippi Valley.

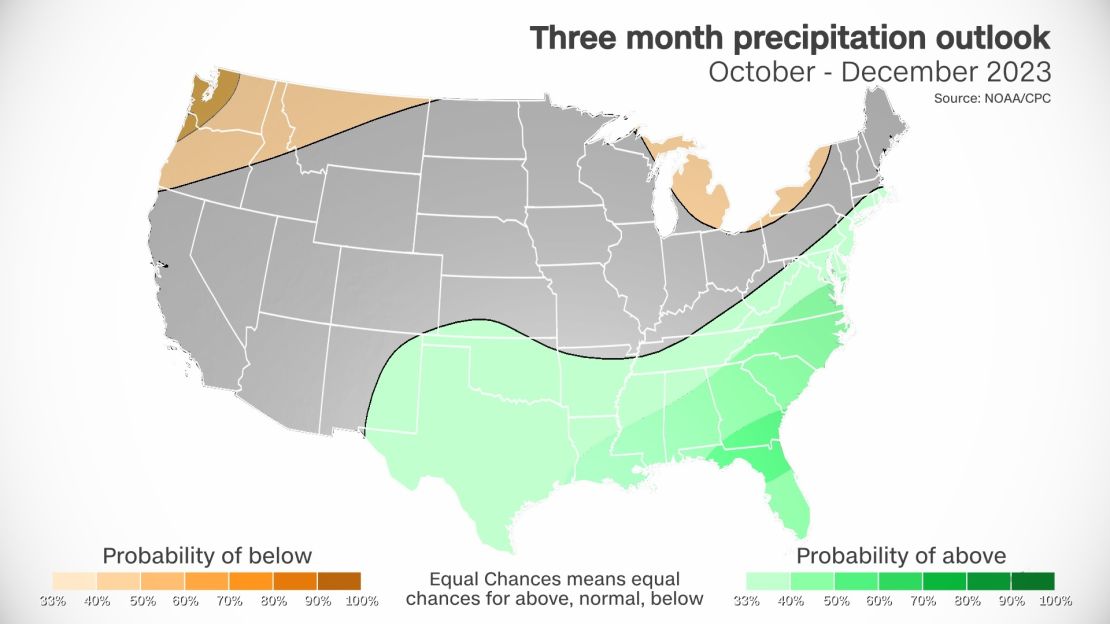

It also shows above-normal precipitation chances over the next three months across the South.

An ongoing El Niño will partly drive this potential drought relief. El Niño winters often feature increases in precipitation across the South.

But an El Niño winter may be a double-edged sword, as portions of the northern Plains and Midwest tend to say drier than average.

Drier conditions may affect rivers which flow into the Mississippi River, like the Missouri and the Ohio, limiting the amount of water feeding into the Mississippi as a whole.

Sixty percent of the water that flows into the lower Mississippi River comes from the Ohio River, while the other 40 percent comes from the upper Mississippi River, Dedeaux told CNN.

CNN Meteorologist Brandon Miller contributed to this story.