The forecast for Idalia is alarming: a so-called rapid intensification as it tracks through the Gulf of Mexico, tapping into some of the warmest waters on the planet ahead of making landfall in Florida this week.

If it does so, it would join a growing list of devastating storms like Hurricane Ian — which leveled coastal Florida and left more than 100 dead — to rapidly intensify before landfall in recent years.

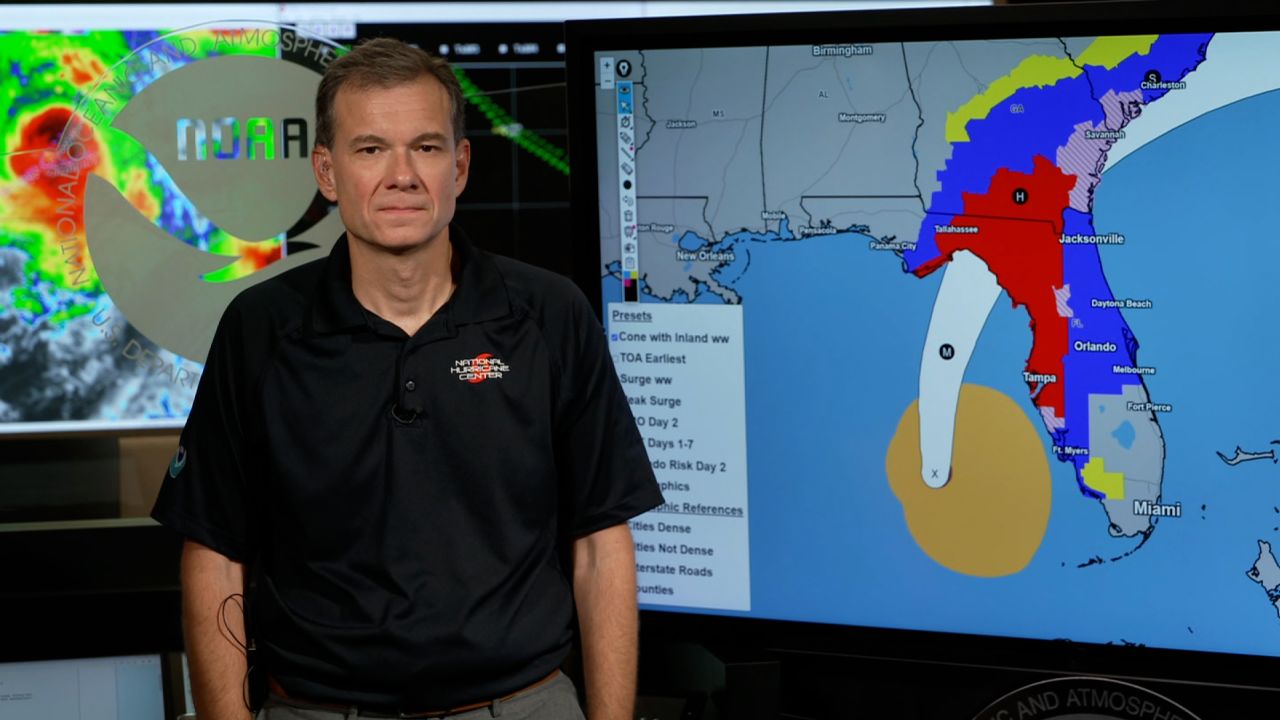

Idalia posed a “notable risk” of this phenomenon, the National Hurricane Center warned Monday, as it travels through the Gulf of Mexico. Water temperatures around southern Florida climbed to 100 degrees Fahrenheit in some areas this summer, and temperatures in the Gulf overall have been record-warm, with more than enough heat to support rapid strengthening.

Ocean temperatures are around “1 to 2 degrees Celsius (roughly 2 to 3.5 degrees Fahrenheit) above normal for this time of year, which is a lot when you consider this is already a super-hot time of year,” Brian McNoldy, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Miami, told CNN. “With that in mind, and with those extra warm waters ahead of it, it does make rapid intensification more likely to happen.”

Rapid intensification is now ‘more likely’

Rapid intensification is precisely what it sounds like — when a storm’s winds strengthen rapidly over a short amount of time. Scientists have defined it as a wind speed increase of at least 35 mph in 24 hours or less.

Concerningly, it has been happening more and more as storms are approaching landfall, making them harder to prepare for and more dangerous to the people who stayed behind expecting a weaker storm.

It’s just one of the ways experts say the climate crisis is making hurricanes more dangerous, as warmer waters allow for storms to strengthen quicker. More than 90% of warming around the globe over the past 50 years has taken place in the oceans, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Until recently, rapidly intensifying storms were less common. Tropical storms historically have taken several days to grow into powerful hurricanes, but with human-caused climate change, rapid intensification is becoming a more common occurrence, said Allison Wing, an assistant professor of atmospheric science at Florida State University.

Hurricane Franklin in the Atlantic Ocean went through two bouts of rapid intensification, most recently from Sunday morning to Monday morning when it strengthened from a 90-mph Category 1 hurricane to a 145-mph Category 4.

“The frequency of cases of rapid intensification has increased in recent years,” Wing told CNN. “While each storm has a unique set of circumstances, climate change makes the occurrence of strong hurricanes that rapidly intensify more likely.”

McNoldy and Wing said two ingredients must come together for rapid intensification to occur: In addition to warm ocean water, the upper-level winds around the hurricane need to be weak. Strong winds can prevent a storm from intensifying or even tear a storm apart.

“There will be a bit of wind shear ahead of (the storm), which might keep it to just a bit of rapid intensification instead of a lot,” McNoldy said. “But there’s still that small component that it can rapidly intensify more than what the models are showing.”

More dangerous storms

Rapid intensification has been historically hard to predict, especially when it comes to capturing where the overall threats and impacts will be and how it can unfold. Andrew Kruczkiewicz, a senior researcher at the Columbia Climate School at Columbia University, warned that Idalia’s impacts could go beyond the point of landfall.

Storm surge, for instance, may happen in and around the area where the storm makes landfall, but heavy rainfall-related hazards can occur as far as 100 miles away, Kruczkiewicz said.

“This is something that we’re seeing more and more, and this is a climate change connection because we’re seeing wetter tropical cyclones and wetter hurricanes,” he told CNN. “So we need to pay more attention to the risks associated with intense precipitation, especially in areas that are distant from the coastline.”

In pictures: Hurricane Ian slams the Southeast

A 2020 study published in the journal Nature found storms are moving farther inland than they did five decades ago. Hurricanes, which typically weaken after moving over land, have been raging longer after landfall in recent years. The study concludes that warmer sea surface temperatures are leading to a “slower decay” by increasing moisture that a hurricane carries.

Kruczkiewicz said areas as far inland as Augusta, Georgia, or Columbia, South Carolina, may be at risk from Idalia.

“These are inland areas that people from the coastline might evacuate to, and think they’re safe, but there’s going to be very high chance of flash flooding in those areas,” Kruczkiewicz said.

Because of the storm’s far-reaching impacts, McNoldy warned not to focus on where the forecast cone is, but rather what’s being forecast in your location.

“Pay attention to your hurricane watches, your storm surge watches and warnings, and your evacuations if you’re told to evacuate,” McNoldy said. “Hopefully, we learned some lessons from last year.”