He was once worshiped by millions, the star cricketer turned populist politician who promised to break the shackles of corruption, ushering Pakistan into a hopeful new era.

Yet the final days of Imran Khan’s political career tell a contrasting tale.

The former Pakistani prime minister was arrested at his home in the city of Lahore Saturday after he was found guilty of corruption and sentenced to three years in prison. Sitting in what his lawyers say is a fly-infested cell in an overcrowded jail about 80 kilometers west of the capital Islamabad, Khan has denied any wrongdoing and lodged an appeal.

But the verdict is likely to bring an end to his hopes of contesting future elections. On Tuesday, election authorities banned Khan from running for office for five years.

Khan alleges that Pakistan’s current government conspired with the country’s army chief to remove him from power – and that his arrest and disqualification are politically motivated.

And despite his ouster in a parliamentary no-confidence vote last year, Khan maintains widespread popularity in the country.

One of the few politicians to challenge Pakistan’s powerful military, he drew tens of thousands to nationwide rallies that became a fixture in the country’s volatile political scene.

Khan’s supporters – some armed with sticks and stones – marched through cities, chanting slogans against the ruling dispensation. Police, dressed in riot gear, retaliated with tear gas, sparking scenes of widespread unrest.

To his supporters, Khan was seen as a political martyr, someone they had vowed to defend till the very end. But the military responded with an extensive crackdown, arresting protesters, censoring journalists and forcing Khan’s aides to resign.

Since his detention Saturday, the streets of Pakistan remain calm, with no hint of upcoming unrest.

Analysts say Khan’s arrest following a yearlong showdown with the military sends a pointed message to the former prime minister and his supporters.

“The state has ways and means to discourage popular protest and street protest,” said prominent Islamabad-based columnist Arifa Noor. “Once the state starts to crack down people fear for their lives.”

Khan’s political rise

That one of Pakistan’s most popular politicians is sitting in a high security prison more commonly used to hold militants is illustrative of the country’s unpredictable modern history.

The South Asian nation of 220 million has, since its inception in 1947, struggled with political and social instability following a traumatic partition that hastily divided British India along religious lines into two independent countries.

It’s a country where militant attacks are frequent, poverty is rampant, and violence against women is widespread. No democratically elected leader has ever completed a full five-year term since its independence. Ruled for much of its 76 years by political dynasties or military establishments, analysts say decades of perceived corruption and nepotism disenfranchised swathes of its population, who were clamoring for a clean break from Pakistan’s past.

Born in 1952 to an affluent family in Lahore, Khan, who received a prestigious education and a degree in philosophy, politics and economics from Oxford University, was seen as the country’s ticket to a clean and nationalist government.

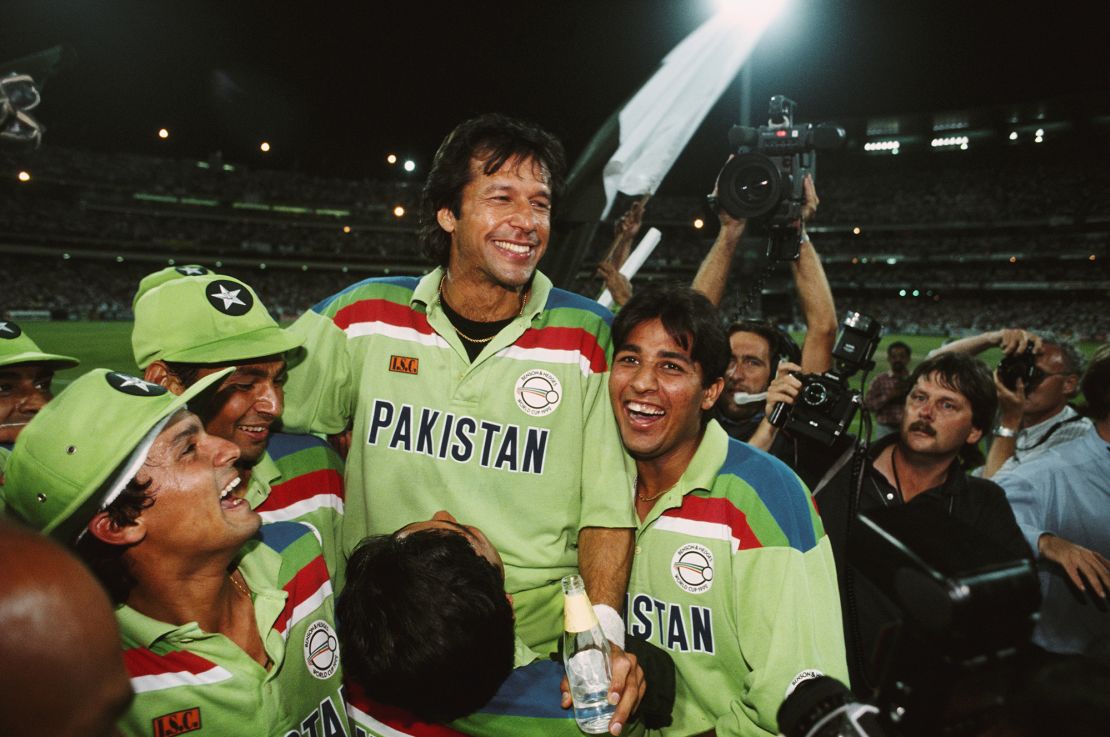

He achieved international fame on the cricket pitch as the formidable captain of Pakistan’s national team, leading the country to its only World Cup victory in 1992. Two years later, Khan opened a cancer hospital and research center in memory of his mother, who died from the illness in 1985, elevating his profile and winning him accolades at home.

His charismatic charm and playboy lifestyle made him a fixture in the tabloids when he married the British heiress and journalist, Jemima Goldsmith, who featured in photographs alongside her former husband and their two young sons attending political rallies.

As his influence in the country grew, Khan’s eyes were now set on politics.

He founded the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI), or the Movement for Justice, in 1996, winning a seat in Parliament in 2002. Khan, who had long since shed his playboy ways to become a much more openly religious figure, soared to new heights of popularity in 2014 when he led protests, accusing the victorious PML-N party of rigging polls.

Finally, after nearly two decades on the political sidelines, Khan was elected prime minister in 2018.

Vowing to eradicate poverty and corruption, he promised a “new Pakistan” to millions in the country.

Tumultuous tenure

Once in office Khan encountered multiple hurdles during his tenure as leader. From rising inflation to a global pandemic, his government grappled with record slumps in foreign exchange, pushing the nation to the brink of economic collapse.

Rising hostilities between Pakistan and neighboring India led to clashes between the two nuclear armed states in 2019, but diplomacy on both sides led to a simmering stalemate that lasted throughout Khan’s premiership. The following year, he received praise for his handling of the coronavirus pandemic after he swiftly closed borders and imposed lockdowns in an attempt to curb the spread of the disease.

But he sparked widespread international criticism in 2021 for his leniency toward the Taliban as their lengthy insurgency barreled towards victory in Afghanistan, instead blaming the United States on the neighboring country’s dire situation.

Once adored by the military, there were now signs of frayed relations, fueled by an anti-American rhetoric that became a focal point of Khan’s foreign policy.

Khan’s government was “not able to implement the sort of changes” nationwide that they had passed at the provincial level, Noor said.

“The PTI’s flagships projects were police reforms and local issues and they weren’t able to deliver on these issues,” she said. “Imran Khan’s political will wasn’t strong enough to begin with from what we saw. The rest of course regarding a new corruption-free Pakistan is a tall ask.”

With his critics citing poor decisions and spiraling inflation, Khan was ousted from power in a parliamentary no-confidence vote last April, setting the stage for nearly a year of, at times, violent protests.

Claiming he was unfairly removed by the military and government in a plot that was sponsored by the US – all three parties have denied the allegations – analysts say Khan was playing on decades-long animosities to mobilize support.

Friction between Khan’s supporters and the authorities came to a head multiple times, most dramatically in May, when he was briefly arrested on different charges, sparking a deadly outpouring of anger.

Pakistan’s Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif called Khan’s supporters “terrorists,” vowing strict punishment. The military responded with a crackdown on dissent, arresting hundreds of protesters and leaders of Khan’s political party.

What happens now?

At age 70, Saturday’s verdict could signal the end of Khan’s political career. But he has vowed to fight on.

In a video recorded prior to his arrest, Khan asked supporters to peacefully protest to ensure their “freedom and human rights,” adding he was going through this “struggle” for the “future of Pakistan’s children.”

But unlike earlier in the year, there has been no sign yet of mass protests from his supporters.

Khan’s conviction relates to an inquiry conducted by the election commission, which found him guilty of not declaring the proceeds from sales of state gifts during his tenure as prime minister.

Some of his allies say the verdict was politically motivated.

“Mr. Khan’s legal team was not allowed to give any legal defense or their statements,” said Syed Zulfiqar Bukhari, the PTI’s international media spokesman. “No leaders are allowed to show their face in public. Everyone is in hiding or an exile.”

And some experts agree.

Constitutional lawyer Salaar Khan pointed out that Khan has “been awarded the maximum sentence,” adding his team was not given adequate time to prepare his defense.

“If you look at what he’s done and you look at other current politicians, they too received gifts and were not held up to the same standards,” he said.

Pakistan’s government has maintained his arrest is “not an issue of political persecution” and that the court made its judgment “following the prescribed legal proceedings.”

On the day of Khan’s arrest, the Pakistani government announced that elections will be held using a new census, which could possibly delay the election date.

Speaking to CNN Monday, Defense Minister Khawaja Asif said the government will likely dissolve Parliament soon, paving the way for a caretaker government to rule until general elections in November – but that a delay is a possibility he won’t rule out.

While Khan won’t be able to contest elections this year, analysts say it would be unwise to rule out a comeback.

“Imran Khan’s story in politics is symbolic of any politician in Pakistan,” said Noor, pointing to previous cases where democratically-elected leaders have been thrown out of power. However, history shows they “become more popular” after being ousted, she added.

“All politicians that enjoy the support of the people make a comeback in Pakistan,” Noor said. “As long as the electorate is supportive then they will return to power.”