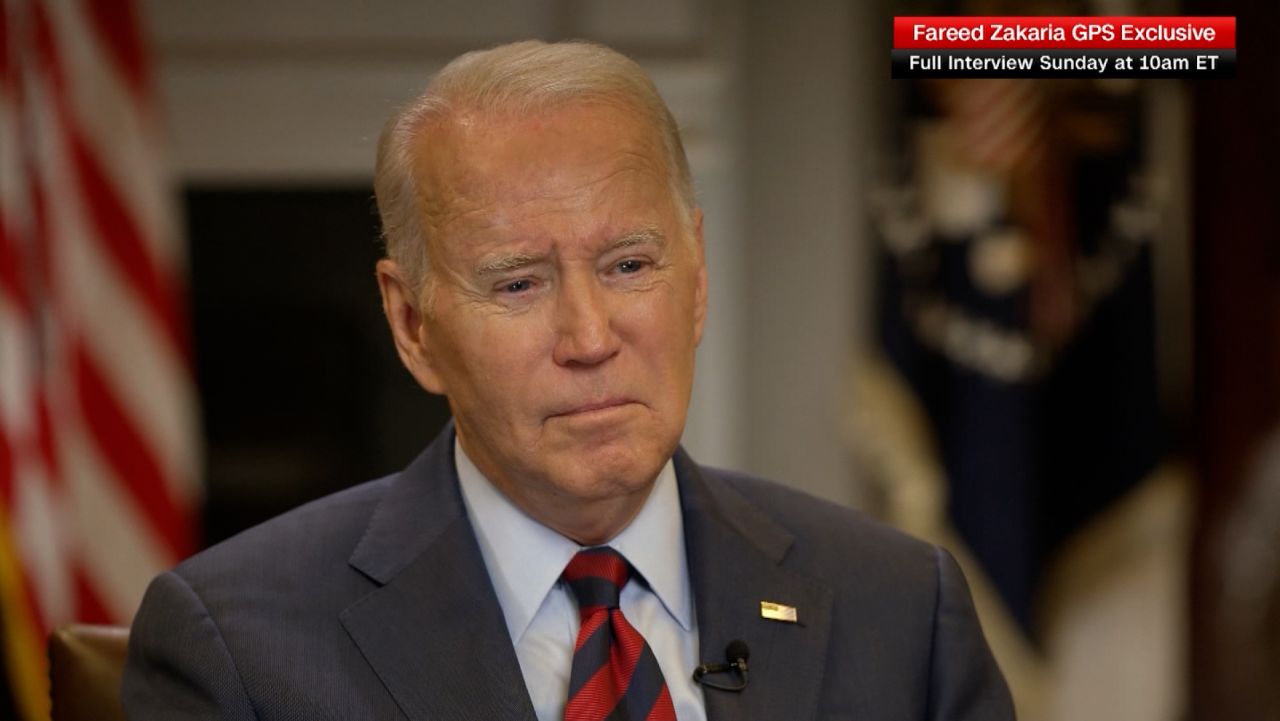

President Joe Biden has already secured a powerful deliverable from his Europe trip – one that will weaken Russia’s strategic position in another detrimental consequence of its invasion of Ukraine.

Turkey’s lifting of its blockade on Sweden’s entry into NATO was a significant and stunning move on the eve of the NATO summit in Lithuania. The reversal by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan came hours after he warned Sweden would be out in the cold until Turkey got its long-delayed membership in the European Union.

Once Sweden finally joins NATO, it will bolster Biden’s reputation as a US leader who reinvigorated and expanded the bloc. Finland – which decided to sign up, like Sweden, after the invasion of Ukraine – has already added hundreds of miles of NATO territory on Russia’s border. Biden’s lifeline of arms and ammunition for Ukraine and leadership of the alliance has made him the most significant president in transatlantic affairs at least since George H.W. Bush, who presided over the end of the Cold War and the reunification of Germany. His legacy will ultimately depend, however, on the outcome of the war in Ukraine and his capacity to avoid a direct clash with Russia.

Turkey’s about-face will also lighten the mood at the NATO summit, where the alliance’s most unified moment in years had been in danger of being somewhat tarnished by divides over Ukraine’s pleas to get a timetable for membership. Biden had said before leaving the US that Ukraine was not ready to join. New member states need unanimous approval of all NATO’s members before they can join the club and benefit from its collective security guarantee.

Erdogan’s move was also a severe blow to Russian President Vladimir Putin. First, it will result in the expansion of NATO territory and strengthen the alliance after an unprovoked invasion of Ukraine that Putin had argued was partly intended to weaken the West and to counter what he claims is its effort to neuter Russia’s power in its own backyard. Secondly, the decision by Erdogan – an increasingly autocratic leader who has enjoyed largely cordial ties with the Kremlin strongman – will frustrate Russia’s attempts to sow divides between NATO members in order to weaken the alliance.

Monday’s events were another intriguing twist for a mercurial leader who has leveraged Turkey’s strategic position where the West meets the East to try to rebuild his country as a major regional power. While it is so far unclear whether Erdogan secured anything more than cosmetic concessions from Sweden, NATO’s European powers and the United States, his sudden change of mind raises the question of whether he had negotiated himself into a corner. He had already dropped objections to Finland joining the alliance.

The newly reelected Erdogan has vexed successive US presidents for years, both over his geopolitical muscle flexing and his hardline rule that Washington fears will erode Turkey’s secular constitution and democracy. In recent years, the US has been frustrated by his cozying up to Putin and also his suggestions, yet to be realized, of a rapprochement with Syria.

Behind the scenes diplomacy after US pressure

NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg, who is very close to Biden and was just persuaded to extend his term until October 2024, said that Turkey’s change of heart was the product of months of diplomacy. “This is not new negotiation, but it is about implementing, and reassuring the implementation of the different things we agreed a year ago in Madrid,” Stoltenberg said.

Turkey’s change of heart also followed a telephone call between Biden and Erdogan on Sunday, in which the American president appears to have made his position crystal clear. The White House hinted at the tone of the call when it said Biden expressed a desire to get Sweden into NATO “as soon as possible.”

US national security adviser Jake Sullivan said the deal came about after talks between NATO, Turkey and Sweden but also pointed to recent US engagement, including the president’s meeting in Washington last week with Swedish Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson.

“We’re coming into this consequential summit with a full head of steam,” Sullivan told reporters in Vilnius following the Sweden deal which he said highlighted a sense of unity that would disappoint Putin. “Every few months, the question is called: Can the West hang together? Can NATO hang together?” he added. “Every time allies gather, that question gets re-upped, and every time the allies come together and answer it forcefully and vehemently: Yes we can.”

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, a New York Democrat, hailed the unpicking of the deadlock and also sought to secure political credit for Biden, whom he saluted as a foreign policy expert. “He has a real grasp of it, a real handle on it, and is very effective. And this is a victory for America, for the West, for freedom, and for President Biden.”

Whether Turkey got any political wins may not emerge for several days. But official media in Ankara quoted a senior official as saying Erdogan secured Sweden’s full support for Turkey’s entry process into the EU, which has been on hold for years. Stoltenberg also expressed strong backing for Turkey’s campaign for EU membership, and Biden said in a statement he was looking forward to enhancing security in Eurasia with the Turkish leader.

All of these steps, however – while possibly giving Erdogan political cover back home for his shift of position – hardly seem like big breakthroughs for Turkey. Stoltenberg, for instance, has no capacity to influence its bid to join the European Union. And Erdogan’s crackdowns on human rights and the media have only increased skepticism about Turkey’s capacity to meet EU entry conditions. Sweden and Turkey did agree to work together to combat terrorism as part of the deal between their leaders, and NATO agreed to appoint a new counter-terrorism coordinator. These steps appear to be aimed at assuaging Erdogan’s demands for a crackdown on the militant Kurdistan Workers’ Party in Sweden. Turkey claims that the Stockholm government had allowed members of the group to operate on its soil and has been complicit in far-right anti-Islam protests.

Another factor that may have weighed on Erdogan was the fact that a group of bipartisan senators had called on Biden to delay the sale of F-16 fighter jets to Turkey, which would be one of the biggest arms sales in years, until it dropped its objections to Sweden’s NATO membership. Sen. Bob Menendez, the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, said Monday he had not yet decided whether to drop his long-standing opposition to the F-16s deal, partly over concern Turkey could use the planes to intimidate fellow NATO member Greece. The New Jersey Democrat said he could make up his mind “in the next week.” Sullivan said that Biden supported the sale of the jets and had placed no caveats or conditions on it in recent weeks in talks with the Turks. He also said the administration had been in touch with Menendez on the issue.

A stunning reversal

Given his hardline position coming into the NATO summit, Erdogan appears to have fallen well short of his own objectives. He warned as recently as Monday morning that Sweden’s membership should be linked to Turkey’s own aspirations to join the EU. “Turkey has been waiting at the gate of the European Union for over 50 years now,” and “almost all NATO member countries are European member countries,” he warned.

Former Deputy Director of National Intelligence Beth Sanner said on CNN on Monday that Erdogan’s sudden shift was “fascinating” because he had essentially been seeking to negotiate quid pro quos with the US for months. “This really isn’t about Sweden, this is about the United States and Turkey and Turkey’s role,” she told Jake Tapper. “He played his hand too hard by putting the EU membership on the table, and I think he really wants to be seen by NATO as the person who comes in and saves the day, not as the spoiler.” She continued: “He started looking like the spoiler and I think he had to back off.”

One major consequence of Erdogan’s reversal could be a souring of his relations with Putin only days after he he invited the Russian leader to Turkey in August. Erdogan wants to wield Turkey’s power to broker an extension to a deal that allows Ukraine to export grain from Black Sea ports.

In another significant move over the weekend, Turkey allowed the release of a group of Ukrainian commanders, who were previously captured by Russia after leading the defense of Mariupol from the Azovstal steel plant last year. They went home to a heroes’ welcome with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky despite a prior agreement with Russia that they would not be handed over to Ukraine until the end of the war.

It looks like Erdogan has made a significant break with Putin. But anyone who expects him to quit playing multiple sides of the great geopolitical game will likely be disappointed. Erdogan has always been about exacting maximum power for himself and Turkey, and that is unlikely to change.

CNN’s Betsy Klein contributed to this report.